|

THE news of the king’s arrival was received

in Scotland with a burst of enthusiasm not quite in accordance with the

national character; but the idea that the nation was about to regain its

liberties made Scotsmen forget their wonted propriety. Preparatory to the

assembling of the Scottish parliament, which was summoned to meet at

Edinburgh on the 1st of January, 1661, Middleton, who had lately been

created an earl, was appointed his majesty’s commissioner; the Earl of

Glencairn, chancellor; the Earl of Lauderdale, secretary of state; the

Earl of Rothes, president of the council; and the Earl of Crawford,

lord-treasurer.

It would be quite apart

from the object of this work to detail the many unconstitutional acts

passed by this "terrible parliament," as it is well named by

Kirkton; but the trial of the Marquis of Argyle must not be overlooked.

That nobleman had, on the restoration of the king, gone to London to

congratulate his majesty on his return; but on his arrival he was

immediately seized and committed to the Tower. He petitioned the king for

a personal interview, which was refused, and, to get rid of his

importunities, his majesty directed that he should be sent back to

Scotland for trial. Being brought to trial, he applied for delay, till

some witnesses at a distance should be examined on commission; but this

also was refused. He thereupon claimed the benefit of the amnesty which

the king had granted at Stirling. This plea was sustained by desire of the

king; but as there were other charges against him, arising out of

transactions subsequent to the year 1651, to which year only the amnesty

extended, the trial was proceeded in. These charges were, that he had

aided the English in destroying the liberties of Scotland — that be had

accepted a grant of £12,000 from Cromwell — that he had repeatedly used

defamatory and traitorous language in speaking of the royal family —

and, lastly, that he had voted for a bill abjuring the right of the royal

family to the crowns of the three kingdoms, which had been passed in the

parliament of Richard Cromwell, in which he sat. Argyle denied that he had

ever given any countenance or assistance to the English in their invasion

of Scotland; but he admitted the grant from Cromwell, which he stated was

given, not in lieu of services, but as a compensation for losses sustained

by him, he, moreover, denied that he had ever used the words attributed to

him respecting the royal family; and with regard to the charge of sitting

in Richard Cromwell’s parliament, he stated that he had taken his seat

to protect his country from oppression, and to be ready, should occasion

offer, to support by his vote the restoration of the king. This defence

staggered the parliament, and judgment was postponed. In the meantime

Glencairn and Rothes hastened to London, to lay the matter before the

king, and to urge the necessity of Argyle’s condemnation. Unfortunately

for that nobleman, they had recovered some letters which he had written to

Monk and other English officers, in which were found some expressions very

hostile to the king; but as these letters have not been preserved, there

precise contents are not known. Argyle was again brought before

parliament, and the letters read in his presence.

He

had no explanation to give, and his friends, vexed and dismayed, retired

from the house and left him to his fate. He was accordingly sentenced to

death on the 25th of May, 1661, and, that he might not have an opportunity

of appealing to the clemency of the king, he was ordered to be beheaded

within forty-eight hours. He prepared for death with a fortitude not

expected from the timidity of his nature; wrote a long letter to the king,

vindicating his memory, and imploring protection for his poor wife and

family; on the day of his execution, dined at noon with his friends with

great cheerfulness, and was accompanied by several of the nobility to the

scaffold, where he behaved with singular constancy and courage. After

dinner he retired a short time for private prayer, and, on returning, told

his friends that "the Lord had sealed his charter, and said to him,

"Son, be of good cheer, thy sins are forgiven." When brought to

the scaffold he addressed the people, protested his innocence, declared

his adherence to the Covenant, reproved "the abounding wickedness of

the land, and vindicated himself from the charge of being accessory to the

death of Charles I." With the greatest fortitude he laid his head

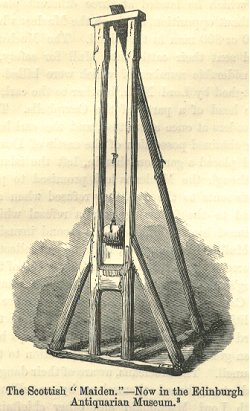

upon the block, which was immediately severed from his body by the maiden.

This event took place upon Monday, the 27th of May, 1661, the marquis

being then 65 years of age. By a singular destiny, the head of Argyle was

fixed on the same spike which had borne that of his great rival Montrose. He

had no explanation to give, and his friends, vexed and dismayed, retired

from the house and left him to his fate. He was accordingly sentenced to

death on the 25th of May, 1661, and, that he might not have an opportunity

of appealing to the clemency of the king, he was ordered to be beheaded

within forty-eight hours. He prepared for death with a fortitude not

expected from the timidity of his nature; wrote a long letter to the king,

vindicating his memory, and imploring protection for his poor wife and

family; on the day of his execution, dined at noon with his friends with

great cheerfulness, and was accompanied by several of the nobility to the

scaffold, where he behaved with singular constancy and courage. After

dinner he retired a short time for private prayer, and, on returning, told

his friends that "the Lord had sealed his charter, and said to him,

"Son, be of good cheer, thy sins are forgiven." When brought to

the scaffold he addressed the people, protested his innocence, declared

his adherence to the Covenant, reproved "the abounding wickedness of

the land, and vindicated himself from the charge of being accessory to the

death of Charles I." With the greatest fortitude he laid his head

upon the block, which was immediately severed from his body by the maiden.

This event took place upon Monday, the 27th of May, 1661, the marquis

being then 65 years of age. By a singular destiny, the head of Argyle was

fixed on the same spike which had borne that of his great rival Montrose.

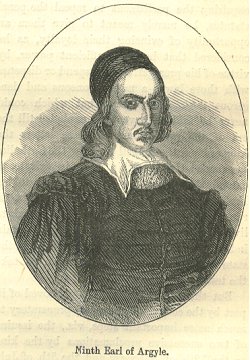

Argyle was held in high

estimation by his party, and, by whatever motives he may have been

actuated, it cannot but be admitted, that to his exertions Scotland is

chiefly indebted for the successful stand which was made against the

unconstitutional attempts of the elder Charles upon the civil and

religious liberties of his Scottish subjects. He appears to have been

naturally averse to physical pain, deficient in personal courage, the

possession of which, in the times in which Argyle lived, "covered a

multitude of sins," and the want of which was esteemed by some

unpardonable. We believe that it is chiefly on this account that his

character is represented by his enemies and the opponents of his

principles in such an unfavourable light, contrasting as it does so

strikingly with that of his great opponent, the brave and chivalrous

Montrose. That he was an unprincipled hypocrite, we think it would be

difficult to prove; genuine hypocrisy, in a mark of his ability, would

have probably gained for its possessor a happier fate. That he was wary,

cunning, reticent, and ambitious, there cannot be any doubt ;—such

qualities are almost indispensable to the politician, and were more than

ordinarily necessary in those times, especially, considering the men

Argyle had to deal with. We believe that he was actuated all along by deep

but narrow and gloomy religious principle, that he had the welfare of his

country sincerely at heart, and that he took the means he thought best

calculated to maintain freedom, and, what he thought, true religion in the

land. As he himself said in a letter to the Earl of Strafford, he thought

"his duty to the king would be best shown by maintaining the

constitution of his country in church and state." On the whole, he

appears to have been a well-meaning, wrong-headed, narrow-minded, clever

politician. Mr. Grainger, in his Biographical History of England, justly

observes, "The Marquis of Argyle was in the cabinet what his enemy,

the Marquis of Montrose, was in the field, the first character of his age

for political courage and conduct." Had he been tried by impartial

judges, the circumstances of the times would have been considered as

affording some extenuation for his conduct; but it was his misfortune to

be tried by men who were his enemies, and who did not scruple to violate

all the forms of justice to bring him to the block, in the hope of

obtaining his vast possessions.

The execution of Argyle was

not in accordance with the views of the king, who, to show his

disapprobation of the death of the marquis, received lord Loin, his eldest

son, with favour at court; from which circumstance the enemies of the

house of Argyle anticipated that they would be disappointed in their

expectations of sharing among them the confiscated estates of the marquis.

To impair, therefore, these estates was their next object. Argyle had

obtained from the Scottish parliament a grant of the confiscated estate of

the Marquis of Huntly, his brother-in-law, on the ground that he was a

considerable creditor, but as Huntly was indebted to other persons to the

extent of 400,000 merks, the estate was burdened to that amount on passing

into Argyle’s possession. Middlleton and his colleagues immediately

passed an act, restoring Huntly’s estate free of incumbrance, leaving to

Huntly’s creditors recourse upon the estates of Argyle for payment of

their debts. Young Argyle was exasperated at this proceeding, and in a

letter to Lord Duffus, his brother-in-law, expressed himself in very

unguarded terms respecting the parliament. This letter was intercepted by

Middleton, and on it the parliament grounded a charge of verbal sedition,

or leasing-making, as the crime is known in the statutory law of

Scotland, an offence which was then capital. Upon this vague charge the

young nobleman was brought to trial before the parliament, and condemned

to death. The enemies of the house of Argyle now supposed that the estates

of the family were again within their grasp; but the king, at the

intercession of Lauderdale, the rival of Middleton, pardoned Loin,

released him from prison after about a year’s confinement, restored to

him the family estates, and allowed him to retain the title of Earl.

After the suppression of

Glencairn’s short-lived insurrection, the Highlands appear to have

enjoyed repose till the year 1674, when an outbreak took place which

threatened to involve the greater part of that country in the horrors of

feudal war, the occasion of which was as follows. The Marquis of Argyle

had purchased up some debts due by the laird of Maclean, for which his

son, the earl, applied for payment; but the laird being unwilling or

unable to pay, the earl apprised his lands, and followed out other legal

proceedings, to make the claim effectual against Maclean’s estates. In

the meantime the latter died, leaving a son under the guardianship of his

brother, to whom, on Maclean’s death, the earl renewed his application

for payment. The tutor of Maclean stated his readiness to settle, either

by appropriating as much of the rents of his ward’s lands in Mull and

Tirey as would be sufficient to pay the interest of the debt, or by

selling or conveying to him in security as much of the property as would

be sufficient to pay off the debt itself; but he required, before entering

into this arrangement, that the earl would restrict his claim to what was

justly due. The earl professed his readiness to comply with the tutor’s

offer; but the latter contrived to evade the matter for a considerable

time, and at length showed a disposition to resist the earl’s demand by

force.

The earl, therefore,

resolved to enforce compliance, and armed with a decree of the Court of

Session, and supported by a body of 2,000 of his tenants and vassals, he

crossed into Mull, in which he landed at three different places without

opposition, although the Macleans had 700 or 800 men in the island. The

Macleans had sent their cattle into Mull for safety, a considerable number

of which were killed or houghed by Lord Neil, brother to the earl, at the

head of a party of the Campbells. The islanders at once submitted, and the

earl having obtained possession of the castle of Duart, and placed a

garrison therein, left the island. Although the Macleans had promised to

pay their rents to the earl, they refused when applied to the following

year, a refusal which induced him to prepare for a second invasion of

Mull. In September, 16th, he had collected a force of about 1,500 men,

including 100 of the king’s troops from Glasgow, under the command of

Captain Crichton, and a similar number of militia-men, under Andrew M’Farlane,

the laird of M’Farlane, the use of which corps had been granted to the

earl on application to the Council. The Macleans, aware of their danger,

had strengthened themselves by an alliance with Lord Macdonald and other

chieftains, who sent a force of about 1,000 men to their aid; but Argyle’s

forces never reached the island, his ships having been driven back damaged

and dismantled by a dreadful hurricane, which lasted two days.

This misfortune, and

intelligence which the earl received from the commander of Duart castle

that the Macleans were in great force in the island, made him postpone his

enterprise. With the exception of 500 men whom he retained for the

protection of his coasts, and about 300 or 400 to protect his lands

against the incursions of the Macleans, he dismissed his forces, after

giving them instructions to reassemble on the 18th of October, unless

countermanded before that time. The earl then went to Edinburgh to crave

additional aid from the government; but receiving no encouragement, he

posted to London, where he expected, with the help of his friend the Duke

of Lauderdale, to obtain assistance. Lord Macdonald and the other friends

of the Macleans, hearing of Argyle’s departure, immediately followed him

to London, and laid a statement of the dispute before the king, who, in

February, 1676, remitted the matter to three lords of the Privy Council of

Scotland for judgment. The earl returned to Edinburgh in June following. A

meeting of the parties took place before the lords to whom the matter had

been referred, but they came to no decision, and the subsequent fate of

Argyle put an end to these differences, although it appears that he was

allowed to take possession of the island of Mull without resistance in the

year 1680.

Except upon one occasion,

now to be noticed, the Highlanders took no share in any of the public

transactions in Scotland during the reigns of Charles the Second and his

brother James. Isolated from the Lowlands by a mountain barrier which

prevented almost any intercourse between them and their southern

neighbours, they happily kept free from the contagion of that religious

fanaticism which spread over the Lowlands of Scotland, in consequence of

the unconstitutional attempts of the government to force episcopacy upon

the people. Had the Highlanders been imbued with the same spirit which

actuated the Scottish whigs, the government might have found it a

difficult task to have suppressed them but they did not concern themselves

with these theological disputes, and they did not hesitate when their

chiefs, at the call of the government, required their services to march to

the Lowlands to suppress the disturbances in the western counties.

Accordingly, an army of about 8,000 men, known in Scottish history by the

name of the "Highland Host," descended from the mountains under

the command of their respective chiefs, and encamped at Stirling on the

24th of June, 1678, whence they spread themselves over Clydesdale,

Renfrew, Cunningham, Kyle, and Carrick, and overawed the whigs so

effectually, that they did not attempt to oppose the government during the

stay of these hardy mountaineers among them. According to Wodrow and

Kirkton, the Highlanders were guilty of great oppression and cruelty, but

they kept their hands free from blood, as it has been correctly stated

that not one whig lost his life during the invasion of these Highland

crusaders. After remaining about eight months in the Lowlands, the

Highlanders were sent home, the government having no further occasion for

their services, but before their departure they took care to carry along

with them a large quantity of plunder they had collected during their

stay.

["But when this

goodlly army retreated homeward, you would have thought by their baggage

they had been at the sack of a besieged city; and, therefore, when they

passed Stirling bridge every man drew his sword to show the world they

hade returned conquerors from their enemies’ land; but they might as

well have showen the pots, pans, girdles, shoes taken off country men's

feet, and other bodily and household furniture with which they were

burdened; and among all, none purchast so well as the two earles Airly and

Strathmore, chiefly the last, who sent home the money, not in purses, but

in bags and great quantities."— Kirkton, pp. 390]

After the departure of the

Highlanders, the Covenanters again appeared upon the stage, and proceeded

so far as even to murder some soldiers who had been quartered on some

landlords who had refused to pay cess. The assassination of Archbishop

Sharp, and the insurrection of the Covenanters under a preacher named

Hamilton, followed by the defeat of the celebrated Graham of Claverhouse

at Drumclog on the 1st of June, 1679, alarmed the government; but the

defeat of the Covenanters by the king’s forces at Bothwell bridge, on

the 22d of June, quieted their apprehensions. Fresh measures of severity

were adopted against the unfortunate whigs, who, driven to despair, again

flew to arms, encouraged by the exhortations of the celebrated Richard

Cameron,—from whom the religious sect known by the name of Cameronians

takes its name,—and Donald Cargill, another enthusiast; but they were

defeated in an action at Airsmoss in Kyle, in which Cameron, their

ecclesiastical head, was killed.

To cheek the diffusion of anti-monarchical

principles, which were spreading fast throughout the kingdom under the

auspices of the disciples of Cameron, the government, on the meeting of

the Scottish parliament on the 28th of July, 1681, devised a test, which

they required to be taken by all persons possessed of any civil, military,

or ecclesiastical office. The parties taking this test were made to

declare their adhesion to the true Protestant religion, as contained in

the original confession of faith, ratified by parliament in the year 1560,

to recognise the supremacy of the king over all persons civil and

ecclesiastical, and to acknowledge that there "lay no obligation from

the national covenant, or the solemn league and covenant, or any other

manner of way whatsoever, to endeavour any alteration in the government in

church or state, as it was then established by the laws of the

kingdom."

The terms of this test were

far from satisfactory to some even of the best friends of the government,

as it was full of contradictions and absurdities, and it was not until the

Privy Council issued an explanatory declaration that they could be

prevailed upon to take it. The Dukes of Hamilton and Monmouth, however,

rather than take the test, resigned their offices. Among others who had

distinguished themselves in opposing the passing of the test, was the Earl

of Argyle, who supported an amendment proposed by Lord Belhaven, for

setting aside a clause excepting the Duke of York, brother to the king,

and the other princes of the blood, from its operation. The conduct of

Argyle gave great offence to the duke, who sat as commissioner in the

parliament, and encouraged his enemies to set about accomplishing his

ruin. The Earl of Errol brought in a bill reviving some old claims upon

his estates, and the king’s advocate endeavoured to deprive him of his

hereditary offices; but the Duke of York interposed, and prevented the

adoption of these intended measures. To gratify his enemies, however, and

to show the displeasure of the court at his recent opposition, Argyle was

deprived of his seat in the Court of Session. But this did not

sufficiently appease their resentment, and, anxious for an opportunity of

gratifying their malice, they hoped that he would refuse to take the test.

Accordingly, he was required to subscribe it: he hesitated, and craved

time to deliberate. Aware of the plot which had been long hatching against

him, and as he saw that if he refused he would be deprived of his

important hereditary jurisdictions, he resolved to take the test, with a

declaratory explanation, which, it is understood, received the approbation

of the Duke of York, to whom the earl had submitted it. The earl then

subscribed the test in presence of the council, and added the following

explanation:-

"I have considered the

test, and am very desirous of giving obedience as far as I can. I am

confident that the parliament never intended to impose contradictory

oaths: Therefore I think no man can explain it but for himself.

Accordingly, I take it so far as it is consistent with itself and the

Protestant religion. And I do declare, that I mean not to bind myself, in

my station, in a lawful way, from wishing and endeavouring any alteration

which I think to the advantage of Church or State, and not repugnant to

the Protestant religion and my loyalty. And this I understand as a part of

my oath." This declaration did not please the council, but as the

Duke appeared to be satisfied, the matter was passed over, and Argyle kept

his seat at the council board.

Although the Duke of York

had been heard to declare that no honest man could take the test,—a

declaration which fully justified the course Argyle had pursued,—yet the

enemies of that nobleman wrought so far upon the mind of his royal

highness as to induce him to think that Argyle’s declaration was a

highly criminal act. The earl, therefore, was required to take the test a

second time, without explanation; and having refused, he was committed a

prisoner to the castle of Edinburgh, and on the slight foundation of a

declaration which had been sanctioned by the next heir to the crown, was

raised a hideous superstructure of high treason, leasing-making, and

perjury.

Argyle was brought to trial

on Monday, the 12th of December, 1681, before the High Court of Justiciary.

The Earl of Queensberry, the justice-general, and four other judges, sat

upon the bench and fifteen noblemen acted as jurors. The absurdity of the

charges, and the iniquity of the attempt to deprive a nobleman, who had,

even in the worst times, shown an attachment to the royal family, of his

fortune, his honours, and his life, were ably exposed by the counsel for

the earl; but so lost was a majority of the judges to every sense of

justice, that, regardless of the infamy which would for ever attach to

them, they found the libel relevant; and on the following day the assize

or jury, of which the Marquis of Montrose, cousin-german to Argyle,

was chancellor, found him guilty. Intelligence of Argyle’s condemnation

was immediately sent to the king, but the messenger was anticipated in his

arrival by an express from the earl himself to the king, who, although he

gave orders that sentence should be passed against Argyle, sent positive

injunctions to delay the execution till his pleasure should be known.

Argyle, however, did not wish to trust to the royal clemency, and as he

understood preparations were making for his execution, he made his escape

from the castle of Edinburgh, disguised as a page carrying the train of

Lady Sophia Lindsay, his step-daughter, daughter of Lord Balcarres, whose

widow Argyle married.

["He was lying a

prisoner in Edinburgh castle in daily expectation of the order arriving

for his execution, when woman’s wit intervened to save him, and he owed

his life to the affection of his favourite step-daughter, the sprightly

Lady Sophia, who, about eight o’clock in the evening of Tuesday, the

20th of December, 1681, effected his escape in the following manner, as

related to Lady Anne Lindsay, by her father, Earl James, Lady Sophia’s

nephew:—’Having obtained permission to pay him a visit of one

half-hour, she contrived to bring as her page a tall, awkward, country

clown, with a fair wig procured for the occasion, who had apparently been

engaged in a fray, having his head tied up. On entering she made them

immediately change clothes; they did so, and, on the expiration of the

half-hour, she, in a flood of tears, bade farewell to her supposed father,

and walked out of the prison with the most perfect dignity, and with a

slow pace. The sentinel at the drawbridge, a sly Highlander, eyed her

father hard, but her presence of mind did not desert her, she twitched her

train of embroidery, carried in those days by the page, out of his hand,

and, dropping it in the mud, "Varlet," cried she, in a fury,

dashing it across his face, "take that—and that too," adding a

box on the ear, "for knowing no better how to carry your lady’s

garment." Her ill-treatment of him, and the dirt with which she had

besmeared his face, so confounded the sentinel, that he let them pass the

drawbridge unquestioned.’ Having passed through all the guards, attended

by a gentleman from the castle, Lady Sophia entered her carriage, which

was in waiting for her; ‘the Earl,’ says a contemporary annalist, ‘steps

up on the hinder part of her coach as her lackey, and, coming forgainst

the weighhouse, slips off and shifts for himself."’—Lives of

the Lindsays, vol. ii. p. 147.]

He went to London, where he

lay some time in concealment, whence he went over to Holland. On the day

of his escape, being the 21st of December, he was proclaimed a fugitive at

the market cross of Edinburgh, and, on the 24th, the Court of Justiciary

passed sentence of death against him, ordered his arms to be reversed and

torn at the market cross of Edinburgh, and declared his titles and estates

forfeited.

In exculpation of their

infamous proceedings, the persecutors of Argyle pretended that their only

object in resorting to such unjustifiable measures, was to force him to

surrender his extensive hereditary jurisdictions, which, they considered,

gave him too great authority in the Highlands, and the exercise of which

in his family, might obstruct the ends of justice; and that they had no

designs either upon his life or fortune. But this is an excuse which

cannot be admitted, for they had influence enough with the Crown to have

deprived Argyle of these hereditary jurisdictions, without having recourse

to measures so glaringly subversive of justice.

The only advantage taken by

the king of Argyle’s forfeiture was the retention of the heritable

jurisdictions, which were parcelled out among the friends of the court

during pleasure. Lord Loin, the earl’s son, had the forfeited estates

restored to him, after provision had been made for satisfying the demands

of his father’s creditors.

During the latter years of Charles II., a

number of persons from England and Scotland had taken refuge in Holland,

to escape state prosecutions with which, they were threatened. Among the

Scottish exiles, besides Argyle, were Sir James Dalrymple, afterwards Earl

of Stair, the celebrated Fletcher of Salton, and Sir Patrick Home of

Polwarth,—all of whom, as martyrs of liberty, longed for an opportunity

of vindicating its cause in the face of their country. The accession of

James II., in 1685, to the crown of his brother, seemed an event

favourable to their plans, and at a meeting which some of the exiled

leaders held at Rotterdam, they resolved to raise the standard of revolt

in England and Scotland, and invited the Duke of Monmouth, also an exile,

and the Earl of Argyle, to join them. Monmouth, who was then living in

retirement at Brussels, spending his time in illicit amours, accepted the

invitation, and having repaired to Rotterdam, offered either to attempt a

descent on England, at the head of the English exiles, or to go to

Scotland as a volunteer, under Argyle. The latter, who had never ceased

since his flight to keep up a correspondence with his friends in Scotland,

had already been making preparations, and by means of a large sum of money

he had received from a rich widow of Amsterdam, had there purchased a ship

and arms, and ammunition. He now also repaired to Rotterdam, where it was

finally arranged that two expeditions should be fitted out,—one for

England, under Monmouth, and the other for Scotland, under the command of

Argyle, who was appointed by the council at Rotterdam captain-general of

the army, "with as full power as was usually given to generals by the

free states in Europe."

On the 2d of May, 1685, the

expedition under Argyle, which consisted of three ships and about 300 men,

left the shores of Holland, and reached Cairston in the Orkneys on the

6th, after a pleasant voyage. The seizure, by the natives, of Spence, the

earl’s secretary, and of Blackadder, his surgeon, both of whom had

incautiously ventured on shore, afforded the government the necessary

information as to the strength and destination of the expedition. A

proclamation had been issued, on the 28th of April, for putting the

kingdom in a posture of defence, hostages had been taken from the vassals

of Argyle as sureties for their fidelity, and all persons whose loyalty

was suspected were either imprisoned or had to find security for their

fidelity to the government; but as soon as the council at Edinburgh

received the intelligence of Argyle’s having reached the Orkneys, they

despatched troops to the west, and ordered several frigates to cruise

among the Western Isles. After taking four Orcadians as hostages for the

lives of his secretary and surgeon, Argyle left the Orkneys on the 7th of

May, and arrived at Tobermory in the isle of Mull on the 11th, whence he

sailed to the mainland, and landed in Kintyre. Here he published a

declaration which had been drawn up in Holland by Sir James Stuart,

afterwards king’s advocate, full of invective against the government,

and attributing all the grievances under which the country had laboured in

the preceding reign to a conspiracy between popery and tyranny, which had,

he observed, been evidently disclosed by the cutting off of the late king

and the ascension of the Duke of York to the throne. It declared that the

object of the invaders was to restore the true Protestant religion, and

that as the Duke of York was, from his religion, as they supposed,

incapable of giving security on that head, they declared that they would

never enter into any treaty with him. The earl issued, a few days

thereafter, a second declaration, from Tarbet, reciting his own wrongs,

and calling upon his former vassals to join his standard. Messengers were

despatched in all directions, bearing aloft the fiery cross, and in a

short time about 800 of his clan, headed by Sir Duncan Campbell of

Auchinbreck, rallied around their chief. Other reinforcements arrived,

which increased his army to 2,500 men; a force wholly insufficient to meet

a body of about 7,000 militia and a considerable number of regular troops

already assembled in the west to oppose his advance.

Although Argyle’s obvious

plan was at once to have dashed into the western Lowlands, where the

spirit of disaffection was deeply prevalent, and where a great accession

of force might have been expected, he, contrary to the advice of some of

his officers, remained in Argyle a considerable time in expectation of

hearing of Monmouth’s landing, and spent the precious moments in chasing

out of his territories a few stragglers who infested his borders. Amid the

dissensions which naturally arose from this difference of opinion, the

royalists were hemming Argyle in on all sides. Whilst the Duke of Gordon

was advancing upon his rear with the northern forces, and the Earl of

Dumbarton with the regular troops pressing him in front, the Marquis of

Athole and Lord Charles Murray, at the head of 1,500 men, kept hanging on

his right wing, and a fleet watched his ships to prevent his escape by

sea. In this conjuncture Argyle yielded to the opinion of his officers,

and, leaving his stores in the castle of Allangreg, in charge of a

garrison of 150 men, he began his march, on the 10th of June, to the

Lowlands, and gave orders that his vessels should follow close along the

coast. The commander of the castle, on the approach of the king’s ships

under Sir Thomas Hamilton, abandoned it five days thereafter, without

firing a single shot, and the warlike stores which it contained,

consisting of 5,000 stand of arms and 300 barrels of powder, besides a

standard bearing the inscription "Against Popery, Prelacy, and

Erastianism," fell a prey to the royalists. The vessels also

belonging to Argyle were taken at the same time.

On the 16th of June Argyle

crossed the Leven near Dumbarton, but finding it impracticable, from the

numerous forces opposed to him, and which met him at every point, to

proceed on his intended route to Glasgow by the ordinary road, he betook

himself to the hills, in the expectation of eluding his foes during the

darkness of the night; but this desperate expedient did not succeed, and

next morning Argyle found his force diminished by desertion to 500 men.

Thus abandoned by the greater part of his men, he, in his turn, deserted

those who remained with him, and endeavoured to secure his own safety.

Disguised in a common dress he wandered for some time in the company of

Major Fullarton in the vicinity of Dumbarton, and on the opposite side of

the Clyde, but was at last taken prisoner by a few militiamen in

attempting to reach his own country. About 100 of the volunteers from

Holland crossed the Clyde in boats, but being attacked by the royalists

were dispersed. Thus ended this ill concerted and unfortunate expedition.

Argyle

was carried to Glasgow, and thence to Edinburgh, where he underwent the

same ignominious and brutal treatment which the brave Montrose had

suffered on being brought to the capital after his capture. As the

judgment which had been pronounced against Argyle, after his escape from

the castle of Edinburgh, was still in force, no trial was considered

necessary. He was beheaded accordingly on the 26th of June, evincing in

his last moments the fortitude of a Roman, and the faith of a martyr.

"When this nobleman’s death," observes Sir Walter Scott,

"is considered as the consequence of a sentence passed against him

for presuming to comment upon and explain an oath which was

self-contradictory, it can only be termed a judicial murder." His two

sons, Lord Loin and Lord Keil Campbell, were banished. Monmouth. who did

not land in England till the 11th of June, was equally unfortunate, and

suffered the death of a traitor on Tower Hill on the 15th of July. Argyle

was carried to Glasgow, and thence to Edinburgh, where he underwent the

same ignominious and brutal treatment which the brave Montrose had

suffered on being brought to the capital after his capture. As the

judgment which had been pronounced against Argyle, after his escape from

the castle of Edinburgh, was still in force, no trial was considered

necessary. He was beheaded accordingly on the 26th of June, evincing in

his last moments the fortitude of a Roman, and the faith of a martyr.

"When this nobleman’s death," observes Sir Walter Scott,

"is considered as the consequence of a sentence passed against him

for presuming to comment upon and explain an oath which was

self-contradictory, it can only be termed a judicial murder." His two

sons, Lord Loin and Lord Keil Campbell, were banished. Monmouth. who did

not land in England till the 11th of June, was equally unfortunate, and

suffered the death of a traitor on Tower Hill on the 15th of July.

The ill fated result of

Argyle’s expedition, and the suppression of Monmouth’s rebellion,

enabled James to turn the whole of his attention to the accomplishment of

an object more valuable, in his opinion, than the crown itself —the

restoration of the Catholic religion. In furtherance of this design, the

king adopted a series of the most unconstitutional and impolitic measures,

which destroyed the popularity he had acquired on his accession, and

finally ended in his expulsion from the throne.

It was not, however, till

the Scottish parliament, which met on the 28th of April, 1686, and on the

obsequiousness of which the king had placed great reliance, had refused to

repeal the test, that he resolved upon those desperate measures which

proved so fatal to him. This parliament was prorogued by order of the king

on the 15th of June, and in a few months thereafter, he addressed a

succession of letters to the council,—from which he had previously

removed some individuals who were opposed to his plans,—in which he

stated, that in requiring the parliament to repeal the penal statutes, he

merely meant to give them an opportunity of evincing their loyalty, as he

considered that he had sufficient power, by virtue of his prerogative, to

suspend or dispense with those laws; a most erroneous and dangerous

doctrine certainly, but which could never be said to have been exploded

till the era of the revolution. In these letters the king ordered the

council to allow the Catholics to exercise their worship freely in

private, to extend the protection of government to his Protestant as well

as Catholic subjects, to receive the conformist clergy in general to

livings in the church, and to admit certain individuals whom he named to

offices in the state without requiring any of them to take the test.

But these letters, though

disapproved of in part by the council, were merely preparatory to much

more important steps, viz., the issuing of two successive proclamations by

the king on the 12th of February and the 5th of July in the following

year, granting full and free toleration to Presbyterians, Catholics, and

Quakers, with liberty to exercise their worship in houses and chapels. He

also suspended the severe penal statutes against the Catholics, which had

been passed during the minority of his grandfather; but he declared his

resolution to preserve inviolate the rights and privileges of the then

established (Episcopal) church of Scotland, and to protect the holders of

church property in their possessions.

By the Presbyterians who

had for so many years writhed under the lash of persecution, these

proclamations were received with great satisfaction; and at a meeting

which was held at Edinburgh of the Presbyterian ministers, who had

assembled from all parts of the country to consider the matter, a great

majority not only accepted the boon with cheerfulness, but voted a loyal

address to his majesty, thanking him for the indulgence he had granted

them. Some there were, however, of the more rigorous kind, who denounced

any communication with the king, whom they declared "an apostate,

bigoted, excommunicated papist, under the malediction of the Mediator;

yea, heir to the imprecation of his grandfather," and who found warm

abettors in the clergy of the Episcopal church in Scotland, who displayed

their anger even in their discourses from the pulpit.

Although the Presbyterians

reaped great advantages from the toleration which the king had granted, by

being allowed the free and undisturbed exercise of their worship, and by

being, many of them, admitted into offices of the state, yet they

perceived that a much greater proportion of Catholics was admitted to

similar employments. Thus they began to grow suspicious of the king’s

intentions, and, instead of continuing their gratitude, they openly

declared that they did not any longer consider themselves under any

obligation to his majesty, as the toleration had been granted for the

purpose of introducing Catholics into places of trust, and of dividing

Protestants among themselves. These apprehensions were encouraged by the

Episcopal party, who, alarmed at the violent proceedings of the king

against the English universities, and the bishops who had refused to read

his proclamation for liberty of conscience in the churches, endeavoured to

instil the same dread of popery and arbitrary power into the minds of

their Presbyterian countrymen which they themselves entertained. By these

and similar means discontent spread rapidly among the people of Scotland,

who considered their civil and religious liberties in imminent danger, and

were, therefore, ready to join in any measure which might be proposed for

their protection.

William, Prince of Orange,

who had married the Princess Mary, the eldest daughter of James, next in

succession to the Crown, watched the progress of this struggle between

arbitrary power and popular rights with extreme anxiety. He had incurred

the displeasure of his father-in-law, while Duke of York, by joining the

party whose object it was to exclude James from the throne, by the

reception which he gave the Duke of Monmouth in Holland, and by his

connivance, apparent at least, at the attempts of the latter and the Earl

of Argyle. But, upon the defeat of Monmouth, William, by offering his

congratulations on that event, reinstated himself in the good graces of

his father-in-law. As James, however, could not reconcile the protection

which the prince afforded to the numerous exiles from England and Scotland

who had taken refuge in Holland, with the prince’s professions of

friendship, he demanded their removal; but this was refused, through the

influence of the prince with the States, and though, upon a hint being

given that a war might ensue in consequence of this refusal, they were

removed from the Hague, yet they still continued to reside in other parts

of Holland, and kept up a regular communication with the Prince. Another

demand made by the king to dismiss the officers of the British regiments

serving in Holland, whose fidelity was suspected, met with the same

evasive compliance; for although William displaced those officers, he

refused commissions to all persons whom he suspected of attachment to the

king or the Catholic faith. The wise policy of this proceeding was

exemplified in the subsequent conduct of the regiments which declared

themselves in favour of the prince’s pretensions.

Early in the year 1687,

William perceived that matters were approaching to a crisis in England,

but he did not think that the time had then arrived for putting his

intended design of invasion into execution. To sound the dispositions of

the people, he sent over in February, that year, Dyckvelt, an acute

statesman, who kept up a secret communication with those who favoured the

designs of his master. Dyckvelt soon returned to Holland, with letters

from several of the nobility addressed to the prince, all couched in

favourable terms, which encouraged him to send Zuleistein, another agent,

into England to assure his friends there that if James attempted, with the

aid "of a packed parliament," to repeal the penal laws and the

test act, he would oppose him with an armed force.

Although the king was aware

of the prince’s intrigues, he could never be persuaded that the latter

had any intention to dispossess him of his crown, and continued to pursue

the desperate course he had resolved upon, with a pertinacity and zeal

which blinded him to the dangers which surrounded him. The preparations of

the prince for a descent on England went on in the meantime with activity;

but a temporary damp was cast on his hopes by reports of the pregnancy of

the queen, an event which, if a son was the result, might prevent the

accession of his wife, the Princess Mary. On the 10th of June, 1688, the

queen gave birth to a prince, afterwards known as the Pretender.

It was not till the month

of September, when James was on the verge of the precipice, that he saw

the danger of his situation. He now began, when too late, to attempt to

repair the errors of his reign, by a variety of popular concessions; but

although these were granted with apparent cheerfulness, and accepted with

indications of thankfulness, it was evident that they were forced from the

king by the necessity of his situation, and might be withdrawn when that

necessity ceased to exist, an idea which appears to have prevailed among

the people.

Being now convinced that

the Prince of Orange contemplated an invasion of England, James began to

make the necessary preparations for defence. In September, 1688, he sent

down an express to Scotland to the members of the Privy Council,

acquainting them with the prince’s preparations, and requiring them to

place that part of his dominions on the war establishment. The militia was

accordingly embodied, the castles of Edinburgh, Stirling, &c.

provisioned, and orders were sent to the chiefs of the Highland clans to

be ready to assemble their men on a short notice. Many persons at first

discredited the report of an invasion from Holland, and considered that it

was a mere device of the king either to raise money or to collect an army

for some sinister purpose but their suspicions were allayed by

intelligence being brought by some seamen from Holland of the warlike

preparations which were making in the Dutch ports. The jealousies which

were entertained of the king’s intentions were dissipated by the dread

of a foreign invasion, and addresses were sent in to the Privy Council

from the different towns, and from the country gentlemen, with offers of

service.

Whilst the Privy Council

were engaged in fulfilling the king’s instructions, they received an

order from his majesty to concentrate the regular army, and despatch it

without delay into England. This force, which did not exceed 3,000 men,

was in a state of excellent discipline, and was so advantageously posted

throughout the kingdom that any insurrection which might break out could

be easily suppressed. As the Prince of Orange had many adherents in

Scotland, and as the spirit of disaffection to the existing government in

the western counties, though subdued, had not been extinguished, the Privy

Council considered that to send the army out of the kingdom under such

circumstances would be a most imprudent step; and they, therefore, sent an

express to the king, representing the danger of such a movement, of which

the disaffected would not fail to avail themselves, should an opportunity

occur. They proposed that the army should remain as it was then stationed,

and that, in lieu thereof, a body of militia and a detachment of

Highlanders, amounting together to 13,000 men, should be despatched to the

borders, or marched into the north of England, to watch the movements of

the king’s enemies in that quarter, and to suppress any risings which

they might attempt in favour of the prince. But, although the Council were

unanimous in giving this advice, the king disregarded it altogether,

reiterated the order he had formerly given, and intimated, that if any of

them were afraid to remain in Scotland, they might accompany the army into

England.

Accordingly, the Scottish

army began its march early in October, in two divisions. The first,

consisting of the foot, at the head of which was General Douglas, brother

of the Duke of Queensberry, who had the chief command of the army, took

the road to Chester; and the second, consisting of the horse, under the

direction of Graham of Claverhouse, as major-general, marched by York.

These detachments, on their arrival at London, joined the English army

under the command of the Earl of Feversham, about the end of October.

To supply the absence of

the regular troops, and to prevent the disaffected from making the capital

the focus of insurrection, a large body of militia, under the command of

Sir George Munro, was quartered in Edinburgh and the suburbs; but no

sooner had the army passed the borders, than crowds from all parts of the

kingdom congregated, as if by mutual consent, in the metropolis, where

they held private meetings, which were attended by the Earls of Glencairn,

Crawford, Dundonald, and others. The objects of these meetings were made

known to the council by spies, who were employed to attend them; and

although they were clearly treasonable, the council had not the courage to

arrest a single individual. Among other things, the leaders of these

meetings resolved to intercept all correspondence between the king and the

council, a task which Sir James Montgomery undertook to see accomplished,

and which he did so effectually that very few despatches reached their

destination.

For several weeks the Privy

Council, owing to this interruption, was kept in a state of painful

uncertainty as to the state of the king’s affairs in England; but at

last an express arrived from the Earl of Melfort, announcing the important

intelligence that the Prince of Orange had landed in England with a

considerable force, and that his majesty had gone to meet him at the head

of his army.

The landing of the prince,

which was effected without opposition on the 5th of November 1688, at

Torbay in Devonshire, excited the greatest alarm in the mind of the king,

who had entertained hopes that a well appointed fleet of thirty-seven

men-of-war, and seventeen fire-ships which had been stationed off the

Gun-fleet under the Earl of Dartmouth, an old and experienced commander,

would have intercepted the prince in his voyage. Unfortunately, however,

for the king, the cruisers which the admiral had sent out to watch the

approach of the enemy had been driven back by the violence of the wind,

and when the fleet of the prince passed the Downs towards its destined

place of disembarkation, the royal fleet was riding at anchor abreast of

the Longsand, several miles to leeward, with the yards and topmasts

struck; and as twenty-four hours elapsed before it could be got ready to

commence the pursuit, the commander, on the representation of his

officers, desisted from the attempt.

As soon as the king had

recovered from the panic into which the news of the prince’s arrival had

thrown him, he ordered twenty battalions of infantry and thirty squadrons

of cavalry to march towards Salisbury and Marlborough, leaving six

squadrons and six battalions behind to preserve tranquillity in the

capital. The prince, who had been led to expect that he would be received

with open arms by all classes on his arrival, met at first with a very

cold reception, and he felt so disappointed that he even threatened to

re-embark his army. Had James therefore adopted the advice given him by

the King of France, to push forward his troops immediately in person and

attack the invader before the spirit of disaffection should spread, he

might, perhaps, by one stroke, have for ever annihilated the hopes of his

son-in-law and preserved his crown; but James thought and acted

differently, and he soon had cause to repent bitterly of the course he

pursued. Owing to the open defection of some of his officers and the

secret machinations of others, the king soon found, that with the

exception perhaps of the Scottish regiments, he could no longer rely upon

the fidelity of his army. On the 20th of November he arrived at Salisbury,

and reviewed a division of the army stationed there; and intended to

inspect the following day, another division which lay at Warminster; but

being informed that General Kirk, its commander, Lord Churchill and

others, had entered into a conspiracy to seize him and carry him a

prisoner to the enemy’s camp, he summoned a council of war, at which

these officers were present, and without making them aware that he was in

the knowledge of such a plot, proposed a retreat beyond the Thames. This

proposition met with keen opposition from Churchill, but was supported by

the Earl of Feversham, his brother the Count de Roye, and the Earl of

Dumbarton, who commanded one of the Scottish foot regiments. The proposal

having been adopted, Churchill and some other officers went over to the

prince during the night.

The army accordingly

retired behind the Thames, and the king, without leaving any particular

instructions to his officers, proceeded to London, to attend a council of

peers which he had summoned to meet him at Whitehall. The departure of the

king was a subject of deep regret to his real friends in the army, and

particularly to the Earl of Dumbarton, and Lord Dundee, who had offered to

engage the enemy with the Scots troops alone. This offer his majesty

thought proper to decline, and in a conference which Dundee and the Earl

of Balcarras afterwards had with him in London, when he had made up his

mind to retire to France, he gave them to understand that he meant to

intrust the latter with the administration of his civil affairs in

Scotland, and to appoint the former the generalissimo of his forces.

In the Scottish Privy

Council there were several persons who were inimical to the king, and who

only waited for a favourable opportunity of offering their allegiance and

services to the Prince of Orange. These were the Marquis of Athole, the

Viscount Tarbet, and Sir John Dalrymple, the Lord-president of the Court

of Session. The two latter, in conjunction with Balcarras, had been

appointed by the council to proceed to England, to obtain personally from

the king the necessary instructions how to act on the landing of the

prince, but on some slight pretext they declined the journey, and

Balcarras, a nobleman of undoubted loyalty, was obliged to go alone, and

had the meeting with his majesty to which allusion has been made. These

counsellors were duly apprised of the advance of the prince, the defection

of some of the king’s officers, and of his return to London; but as the

result of the struggle seemed still to be dubious, they abstained from

openly declaring themselves. In order, however, to get rid of the

chancellor, the Earl of Perth, and get the government into their own

hands, as preliminary to their designs, Viscount Tarbet proposed that,

with the exception of four companies of foot and two troops of horse to

collect the revenue, the remainder of the troops should be disbanded, as

he considered it quite unnecessary to keep up such a force in time of

peace, the Prince of Orange having stated in a declaration which he had

issued, that that was one of the grievances complained of by the nation.

The chancellor, not foreseeing the consequences, assented to the proposal,

and he had the mortification, after the order for dismissal had been

given, to receive an intimation from the Marquis of Athole and his party,

who waited personally upon him at his lodgings, that as they considered it

dangerous to act with him and other Catholic counsellors who were

incapacitated by law, they meant to take the government into their own

hands in behalf of the king, and they demanded that he and his party

should retire from the administration of affairs. The Duke of Gordon and

the other Catholic members of the council, on hearing of this proceeding,

assembled in the chancellor’s house to consult with him as to the nature

of the answer which should be given to this extraordinary demand. As they

saw resistance hopeless, they advised the chancellor to submit, and,

probably to avoid personal danger, he retired immediately to the country.

The Marquis of Athole

called a meeting of the council, and proposed an address of congratulation

to the Prince of Orange, strongly expressive of gratitude to him for his

generous undertaking to relieve them from popery and arbitrary power, and

offering a tender of their services; but this address was warmly opposed

by the two archbishops, Sir John Dalrymple, Sir George Mackenzie and

others, and was finally negatived. They even opposed the voting of any

address under existing circumstances, but the marquis and his party

succeeded in carrying a short address, drawn up in general terms. Lord

Glammis was sent up with it, but it was so different from what the Prince

expected, that it met with a very cold reception.

The fate of the unfortunate

monarch had by this time been decided. Before his return to London a great

defection had taken place among the officers of the army, and he had at

last the mortification to see himself deserted by his son-in-law, Prince

George of Denmark, and by his daughter the Princess Anne, the wife of the

Prince. "God help me my very children have forsaken me ;" such

was the exclamation uttered by the unhappy monarch, his countenance

suffused with tears, when he received the afflicting intelligence of the

flight of Anne from Whitehall. When the king saw he could no longer resist

the torrent of popular indignation, and that an imperious necessity

required that he should leave the kingdom, his first solicitude was to

provide for the safety of the queen and his son, whom he managed to get

safely conveyed to France.

The resolution of the king

to quit the kingdom was hastened after a fruitless attempt at negotiation

with the Prince of Orange, by the appearance of an infamous proclamation

against Catholics, issued under the signature of the prince, and which,

though afterwards disowned by him, was, at the time, believed to be

genuine. Having, therefore, made up his mind to follow the queen without

delay, the king wrote a letter to the Earl of Feversham, the commander of

the forces, intimating his intention, and after thanking him and the army

for their loyalty, he informed them that he did not wish them any longer

to run the risk of resisting "a foreign army and a poisoned

nation." Shortly after midnight, having disguised himself as a

country gentleman, he left the palace, and descending by the back stairs,

entered into a hackney coach, which conveyed him to the horse-ferry,

whence he crossed the river, into which the king threw the great seal.

Having arrived at Emley ferry near Feversham by ten o’clock, he embarked

on board the custom-house boy, but before she could be got ready for sea

the king was apprehended, and placed under a strong guard.

When the king’s arrest

was first reported in London, the intelligence was not believed; but all

uncertainty on the subject was removed by a communication from James

himself in the shape of a letter, but without any address, which was put

into the hands of Lord Mulgrave by a stranger at the door of the council

chamber at Whitehall. A body of about thirty peers and bishops had, on the

flight of the king, formed themselves into a council, and had assumed the

reins of government, and many of these, on this letter being read, were

desirous of taking no notice of it, lest they might, by so doing,

displease the prince. Lord Halifax, the chairman, who favoured the prince’s

designs, attempted to quash the matter, by adjourning the meeting, but

Mulgrave prevailed on the members of the council to remain, and obtained

an order to despatch the Earl of Feversham with 200 of the life-guards to

protect the person of the king.

On the arrival of Feversham

the king resolved to remain in the kingdom, and to return to London, a

resolution which he adopted at the urgent entreaty of Lord Winchelsea,

whom, on his apprehension, he had appointed lord-lieutenant of Kent. James

was not without hopes that the prince would still come to terms, and to

ascertain his sentiments he sent Feversham to Windsor to invite the prince

to a personal conference in the capital, and to inform him that St. James’s

palace would be ready for his reception. The arrival of the earl with such

a proposal was exceedingly annoying to William and his adherents, the

former of whom, on the supposition that the king had taken a final adieu

of the kingdom, had begun to act the part of the sovereign, while the

latter were already intriguing for the great offices of the state. Instead

of returning an answer to the king’s message, William, on the pretence

that Feversham had disbanded the army without orders, and had come to

Windsor without a passport, ordered him to be arrested, and committed a

prisoner to the round tower, an order which was promptly obeyed.

At Rochester, whence he had

despatched Feversham, the king was met by his guards, and thence proceeded

to London, which he entered on the 16th of December amidst the

acclamations of the citizens, and the ringing of bells, and other popular

manifestations of joy, a remarkable proof of the instability and

inconstancy of feeling which actuate masses of people under excitement.

As James conceived that the

only chance he now had of securing the confidence of his subjects and

preserving his crown, consisted in giving some signal proof of his

sincerity to act constitutionally, he made the humiliating offer to Lewis

and Stamps, two of the city aldermen, to deliver himself up into their

hands on receiving an assurance that the civil authorities would guarantee

his personal safety, and to remain in custody till parliament should pass

such measures as might be considered necessary for securing the religion

and liberties of the nation. But Sir Robert Clayton dissuaded the common

council from entering into any engagement which the city might possibly be

unable to fulfil, and thus a negotiation was dropt, which, if successful,

might have placed William in a situation of great embarrassment.

But although James did not

succeed in his offer to the city, his return to Whitehall had changed the

aspect of affairs, and had placed William in a dilemma from which he could

only extricate himself by withdrawing altogether his pretensions to the

crown, or by driving his uncle out of it by force. William considered that

the most safe and prudent course he could pursue would be to force James

to leave the kingdom; but in such a manner as to induce the belief that he

did so freely and of his own accord. Accordingly, to excite the king’s

alarms, a body of Dutch guards, by order of the prince, marched into

Westminster, and, after taking possession of the palace of St. James’s,

marched with their matches lighted to Whitehall, of which they also

demanded possession. As resistance, owing to the great disparity of

numbers, was considered by the king to be unavailing, he, contrary to the

opinion of Lord Craven, the commander of his guards, who, though eighty

years of age, offered to oppose the invaders, ordered the guards to resign

their posts, of which the Dutch took possession. This event took place

late on the evening of the 16th of December.

["A day or two after

his return, Earl Colin (of Balcarras) and his friend Dundee waited on his

Majesty. Colin had been in town but three or four days, which he had

employed in endeavours to unite his Majesty’s friends in his interest.

‘He was received affectionately,’ says his son, ‘but observed that

there were none with the king but some of the gentlemen of his

bed-chamber. L— came in, one of the generals of his army disbanded about

a fortnight before. He informed the king that most of his generals and

colonels of his guards had assembled that morning upon observing the

universal joy of the city upon his return; that the result of their

meeting was to appoint him to tell his Majesty that still much was in

their power to serve and defend him; that most part of the army disbanded

was either in London or near it; and that, if he would order them to beat

their drums, they were confident twenty thousand men could be got together

before the end of next day.—’ My lord,’ says the king, ‘I know you

to be my friend, sincere and honourable; the men who sent you are not so,

and I expect nothing from them. ‘—He then said it was a fine day—he

would take a walk. None attended him but Colin and Lord Dundee. When he

was in the Mall, he stopped and looked at them, and asked how they came to

be with him, when all the world had forsaken him and gone to the Prince of

Orange? Colin said their fidelity to so good a master would ever be the

same; they had nothing to do with the Prince of Orange,—Lord Dundee made

the strongest professions of duty ;—‘ Will you two, as gentlemen, say

you have still attachment to me?’—’ Sir, we do.’— ‘Will you

give me your hands upon it, as men of honour?’ they did so,—’ Well,

I see you are the men I always took you to be; you shall know all my

intentions. I can no longer remain here but as a cypher, or be a prisoner

to the Prince of Orange, and you know there is but a small distance

between the prisons and the graves of kings ; therefore I go for France

immediately; when there, you shall have my instructions,—you, Lord

Balcarres, shall have a commission to manage my civil affairs, and you,

Lord Dundee, to command my troops in Scotland.’ "—Lives of the

Lindsays, vol. ii. pp. 161, 162.]

The king now received

orders from William to quit Whitehall by ten o’clock next morning, as

the latter meant to enter London about noon, and that he should retire to

Ham, a house in Surrey belonging to the dowager duchess of Lauderdale,

which had been provided for his reception. The king objected to Ham as a

residence being uncomfortable, but stated his willingness to return to

Rochester. Permission being granted by the prince, James left Whitehall

about twelve o’clock noon, after taking an affectionate adieu of his

friends, many of whom burst into tears. He embarked on board the royal

barge, attended by Viscount Dundee and other noblemen, and descended the

river, surrounded by several boats filled with Dutch guards, in presence

of an immense concourse of spectators, many of whom witnessed with sorrow

the humiliating spectacle.

The king arrived at

Rochester the following day from Gravesend, where he had passed the

previous night. Having remained four days at Rochester, he, accompanied by

two captains in the navy, his natural son the Duke of Berwick, and a

domestic, went on board the Eagle fireship, being unable to reach, on

account of the unfavourable state of the weather, a fishing smack which

had been hired for his reception. On the following morning he went on

board the smack, and after a boisterous voyage of two days, arrived at

Ambleteuse, in France, on the 25th of December, and joined his wife and

child, at the castle of St. Germain’s, on the 28th. Thus ingloriously

and sadly ended the reign of the last of the unfortunate and seemingly

infatuated royal race of Stuarts.

Considering the crisis at

which matters had arrived, the course which the king pursued, of

withdrawing from the kingdom, was evidently the most prudent which could

be adopted. All his trusty adherents in England were without power or

influence, and in Scotland the Duke of Gordon was the only nobleman who

openly stood out for the interests of his sovereign. He had been created a

duke by Charles II. James had appointed

him governor of the castle of Edinburgh, and he had been thereafter made a

privy-counsellor and one of the lords of the treasury. Though a firm and

conscientious Catholic, he was always opposed to the violent measures of

the court, as he was afraid that however well meant, they would turn out

ruinous to the king; not indeed that he did not wish to see the professors

of the same faith with himself enjoy the same civil privileges as were

enjoyed by his Protestant countrymen, but because he was opposed to the

exercise of the dispensing power at a time when the least favour shown to

the professors of the proscribed faith was denounced as an attempt to

introduce popery. The king, influenced by some of his flatterers, received

the duke coldly on his appearance at court in March, 1688, and curtailed

some of his rights and privileges over the lands of some of his vassals in

Badenoch. Even his fidelity appeared to be questioned, by various acts of

interference with the affairs of the castle, of which he disapproved. He

resented these indignities by tendering his resignation of the various

appointments he held from the crown, and demanded permission from the king

to retire beyond seas for a time; but James put a negative upon both

proposals, and the duke returned to his post at Edinburgh.

Notwithstanding the bad

treatment he had received, the duke, true to his trust, determined to

preserve the castle of Edinburgh for the king, although the Prince of

Orange should obtain possession of every other fortress in the kingdom. He

requested the privy council to lay in a quantity of provisions and

ammunition, but this demand was but partially attended to, for though the

garrison consisted only of 120 men, there was not a sufficiency of

materials for a three months siege. The duke shut himself up in the

castle, and invited the Earl of Perth, the chancellor, to join him; but

the earl declined the offer, and, in attempting to make his escape to the

continent, was seized near the Bass, in the Frith of Forth, by some seamen

from Kirkcaldy, under a warrant from the magistrates of that burgh, and.

committed to Stirling castle, where he remained. a close prisoner for

nearly four years. A few days after the duke had retired to the castle, an

attempt was made by some of the prince’s adherents to corrupt the

fidelity of the garrison, by circulating a false report that the duke

meant to make the whole garrison, who were chiefly Protestants, swear to

maintain the Catholic religion. A mutiny was on the eve of breaking out,

but it was detected by the vigilance of some officers. The duke,

thereupon, drew out the garrison, assured them that the report in question

was wholly unfounded, and informed them that all he required of them was

to take the oath of allegiance to the king, which was immediately done by

the greater part of the garrison. Those who refused were at once

dismissed. To supply the deficiency thus made, the duke sent notice to

Francis Gordon of Midstrath to bring up from the north 45 of the best and

most resolute men he could find on his lands; but, on their arrival at

Leith, a hue and cry was raised that the duke was bringing down Papists

and Highlanders to overawe the Protestants. To calm the minds of the

people, the duke ordered these men to return home.

As soon as the news of the

arrival of the Prince of Orange in London, and the departure of the king,

was received in Edinburgh, an immense concourse of persons, "of all

sorts, degrees, and persuasions," who "could (says Balcarras)

scrape so much together" to defray their expenses, went up to London,

influenced by motives of interest or patriotism. The Prince of Orange took

the wise expedient of obtaining all the legal sanction which, before the

assembling of a parliament, could be given to his assumption of the

administration of affairs in England; obtaining the concurrence of many of

the spiritual and temporal peers, and of a meeting composed of some

members who had sat in the House of Commons during the reign of Charles

II., as also of the Lord-Mayor of London, and. 50 of the common council.

He now adopted the same expedient as to Scotland, and taking advantage of

the great influx into the capital of noblemen and gentlemen from that

country, he convened them together. A meeting was accordingly held at

Whitehall, at which 30 noblemen and 80 gentlemen attended. The Duke of

Hamilton, who aimed at the chief direction of affairs in Scotland, was

chosen president. At this meeting a motion was made by the duke that a

convention of the estates should be called as early as possible, and that

an address should be presented to the prince to take upon him the

direction of affairs in Scotland in the meantime; but this motion was

unexpectedly opposed by the Earl of Arran, the duke’s eldest son, who

proposed that the king should be invited back on condition that he should

call a free parliament for securing the civil and religious liberties of

Scotland. This proposition threw the assembly into confusion, and a short

adjournment took place, but on resuming their seats, the earl’s motion

was warmly opposed by Sir Patrick Hume, and as none of the members offered

to second it, the motion was consequently lost, and the duke’s being put

to the vote, was carried.

A convention of the

estates, called by circular letters from the prince, was accordingly

appointed to be held at Edinburgh, on the 14th of March, 1689, and the

supporters of the prince, as well as the adherents of the king, prepared

to depart home to attend the ensuing election. But the prince managed to

detain them till he should be declared king, that as many as might feel

inclined might seal their new-born loyalty by kissing his hand but William

had to experience the mortification of a refusal even from some of those

whom he had ranked amongst his warmest friends. The Earl of Balcarras and

Viscount Dundee, the former of whom had, as before mentioned, been

invested by the king with the civil, the latter with the military

administration of affairs in Scotland, were the first of either party who

arrived in Scotland, but not until the end of February, when the elections

were about to commence. On their arrival at Edinburgh they found the Duke

of Gordon, who had hitherto refused to deliver up the castle, though

tempted by the most alluring offers from the prince, about to capitulate,

but they dissuaded him from this step, on the ground that the king’s

cause was not hopeless, and that the retention of such an important

fortress was of the utmost importance.

The elections commenced.

The inhabitants of the southern and western counties (for every

Protestant, without distinction, was allowed to vote), alarmed for the