The first Scotsman who

dabbled successfully in finance in England was King James VI. He was constantly talking about

money and his acute need of it, and the fact that he managed things so well

as he did on his slender and uncertain income indicated that he had a

business head on his shoulders. He was not above selling titles to swell his

purse, and he was always on the look-out for private undertakings that gave

promise of producing substantial dividends. On more than one occasion he

took a half-interest in enterprises of that character—with or without the

sanction of the promoter—and it is a curious fact that his gambles were

invariably successful. [When Hugh Middleton proposed building the first

canal that supplied London with water, King James took a hand in the scheme,

paying half the cost of construction. For this, however, he demanded half

the property. Actually, he received thirty-six "King's Shares", which King

Charles sacrificed for £500. At the end of the last century one of these

undivided shares sold for £94,900I]

A far more constructive and

dramatic force in English finance, however, was William Paterson, who

founded the Bank of England in 1694. This Scot really understood the

principles of private business and public finance. He combined sound

business sense with spacious ideas about the development of the Empire, and

the curious contradiction of his life was that he established the most

powerful financial institution that England has ever seen, and then led

Scotland to the greatest financial disaster that she has ever encountered.

Paterson was born on a farm

at Skipmyre, in the parish of Tinwald, Dumfriesshire, in the year 1658. Soon

after leaving school he walked down into England with a pack on his back and

a few shillings in his pocket. He settled at Bristol, became interested in

the West India trade, made a fortune, and became a member of the Merchant

Taylors Company in November of 1681.

During the next decade the

picture of his career is rather hazy, but he was a substantial man of

affairs, and was undoubtedly active in more than one commercial enterprise.

He emerged from temporary obscurity in 1691, to make history in England ;

for in that year, with Michael Godfrey and several other prosperous

merchants supporting him, he approached the Government with the proposal

that he and his partners establish a bank to be known as the Bank of

England.

Paterson's associates were

not very active, but he kept the scheme alive, pursued the Government with

it, and finally succeeded, in January of 1692, in bringing matters to a

head. He appeared before a parliamentary committee, and stated that "himself

and some others might come forward to advance £500,000". Presto! The

Government's apathy vanished, and in 1694 the Bank of England came into

existence, with Paterson dominating its Board of Directors.

Such was the contribution of

this Dumfriesshire farmer's son to the financial development of England. He

had accomplished something of incalculable value to the country, but the

next phase of his life was a tragedy, largely as a result of the treatment

he received from the King and the Government of the day. [In all the

historical references to Paterson that we have read, there is not a word

about the suitability of the Isthmus of Darien for colonization purposes.

Its development has never justified Paterson's optimism.]

While the Bank of England was

still in its swaddling clothes, he conceived the idea of colonizing the

Isthmus of Darien. It looked like a promising scheme, and its promoter

enjoyed a sound reputation. The British public was soon infected by his

boundless enthusiasm. He visited Scotland in 1695 to ascertain the feeling

of his own countrymen towards the project. He found that they were more than

ready to support a scheme that promised to give them trading opportunities

which England had denied them. [The Navigation Laws, framed for the benefit

of English shipping, had crippled the ports of Scotland, preventing them

from competing for colonial trade on an equal basis with English ports.]

Convinced that his grandiose scheme would revive trade in Great Britain, and

produce untold wealth by opening up the vast gold-mines that were supposed

to exist in the Isthmus, Paterson went ahead. He raised £300,000 in England.

Scottish subscriptions began to flow in.

At this promising stage of

the promotion trouble developed. The English-owned East India Company used

its influence to discredit and cripple the scheme. It scurried to the

Government, asking for an investigation, and the result of the lobbying was

that Parliament sent a gelatinous address to the King, stating: "That by

reason of the superior advantages granted to the Scottish East India

Company, and the duties imposed upon the India trade in England, a great

part of the stock and shipping of this nation would be carried thither, by

which means Scotland would be rendered a free port, and Europe from thence

supplied with the products of the East much cheaper than through them, and

thus a great article in the balance of foreign commerce would be lost to

England, to the prejudice of the national navigation and the royal revenue";

and, in the same wheedling document: "That when the Scots should have

established themselves in plantations in America, the western branch of

traffic would also be lost, the privileges granted their company would

render their country the general storehouse for tobacco, sugar, cotton,

hides, and timber ; the low rates at which they would be enabled to carry on

their manufactures would render it impossible for the English to compete

with them ; while, in addition, His Majesty stood engaged to protect, by the

naval strength of England, a company whose success was incompatible with its

existence."

The King could not permit the

English East India Company to be subjected to competition from a concern

controlled by Scots, so, remarking that "he had been ill-served in Scotland,

but hoped some remedy would be found to prevent the inconvenience that might

arise from the act", he pacified his parliament by dismissing his Scottish

ministers. Parliament, taking the royal cue, declared William Paterson and

twenty-one other members of the Company guilty of a high misdemeanour.

[How different was the

attitude of King and parliament towards the South Sea Company, the English

trading company organized in 1711. It was readily granted a monopoly of

British trade with South America and the Pacific Islands, and King George I

became its governor in 1718. In the following year, in order to gain

additional trading concessions, the Company had the effrontery to propose

that they take over the National Debt, then standing at £51,300,000, for a

cash consideration £3.500,000. The idea behind the proposal was to get the

annuitants of the State to exchange their annuities for South Sea stock, and

as the Company's stock was to be issued at a high premium a large amount of

annuities would be extinguished by a comparatively small issue of South Sea

stock. In addition to this pleasant feature of the transaction, the Company

was to receive £1,500,000 a year as interest from the Government.

The ridiculous proposition

was accepted by the Earl of Sunderland, then Prime Minister; but the Company

had to raise its bid to £7,567,000 —in order to meet the competition of the

Bank of England! The Government annuitants readily exchanged their annuities

for shares in the Company, and a boom followed, the new stock soaring from

128½ to 1000 in seven months. The inevitable crash came within the year, and

the stock fell to 135, spreading ruination throughout England.

A parliamentary investigation

followed, of course, and it disclosed that the Company's books contained

fictitious entries, that members of the Cabinet had accepted bribes from the

directors of the bubble and had made fortunes by speculating in the stock,

and that the Prime Minister, John Aislabie, the Chancellor of the Exchequer,

and James Craggs, the Postmaster-General, were implicated in the scandal.

Walpole managed to get the Prime Minister acquitted ; Craggs died before

justice overtook him; and Aislabie, after being found guilty of "the most

notorious, dangerous, and infamous corruption", and, serving a short term in

prison, retired to his country estate in Yorkshire. That county, apparently,

had not invested in South Sea stock, for the son of John Aislabie succeeded

his father as Member of Parliament for Ripon in 1721, and held his seat till

1781!]

The impeachment did not

materialize, but the petty and malicious campaign of the English parliament

had accomplished the anticipated results. The English subscription had to be

abandoned. Nevertheless, Paterson continued to promote his badly crippled

venture. In spite of the obstructive tactics of the English Government, more

than £200,000 sterling was subscribed to the scheme by merchants of Holland

and Hamburg, who had learned to have confidence in Scottish methods of

business. The English Government, however, could not suffer to see that

foreign money flowing towards Scotland, so the English Ambassador at Hamburg

was instructed by King William to present a remonstrance to the magistrates

of the German city, complaining of the countenance they had given to the

promoters of the Darien Company.

The reply of the Hamburg

subscribers is worth recording, for it cuts across the devious proceedings

of the English obstructionists like a knife. "We consider it strange", wrote

the hard-headed Hamburgers, "that the King of England should dictate to us,

a free people, how, or with whom, we are to engage in the arrangements of

commerce, and still more so that we should be blamed for offering to connect

ourselves in this way with a body of Your Majesty's own subjects

incorporated under a special Act of Parliament".

However, the confidence of

the Hamburgers had, naturally enough, been seriously shaken by the

propaganda from England, and they began to withdraw their subscriptions. The

Dutch, equally alarmed, withdrew their support.

William Paterson was left in

an appalling predicament, but the impoverished Scottish people, in one of

the most laudable bursts of courage, tenacity, and race loyalty that they

have ever displayed, rallied to his support with a perfectly astounding

unanimity. They actually subscribed £400,000 to the tottering scheme—a sum

calculated to be more than half of the total circulating capital of the

country at that time. The money came from rich and poor alike, in a

never-ending stream. Never, in all her history, has Scotland been so

magnificently loyal to a doomed cause. Her unwavering and heedless support

of Paterson gave the world a glimpse of the terrible courage that can be

generated, on occasion, north of the Cheviot Hills.

There is no need to dwell at

length upon the tragic fate of the Darien Scheme. Paterson went ahead with

it, supplies were bought for the colonizers, and on 26th July, 1698, the

expedition, consisting of five ships carrying twelve hundred men, recruited

from good Scottish families, set sail from Leith for the Eldorado. William

Paterson led the expedition. It reached its destination, but on the soil of

Darien a succession of unforeseen calamities overtook the colonists. The

climate was unhealthy, the natives were hostile; the colonial satraps,

acting on orders from the still hostile England, saw to it that the

colonists were denied the food of which they soon found themselves in

desperate need; and finally quarrels paralysed the diffused management and

spread hopeless dejection among the colonists.

The end of the scheme was in

sight. William Paterson himself succumbed to fever, and later, in New York,

was for a time mentally unbalanced by the shocking nervous strain which he

had undergone. Nowadays men in his position shoot themselves on divans,

inhale carbon-monoxide, or fall out of aeroplanes. William Paterson was

fashioned of different stuff. He came back to Scotland, faced his public,

made a report on the ill-fated enterprise, and even tried to resuscitate it.

The Scottish people forgave him, as we shall see.

Most people would assume that

a man who had been the central figure of such a calamitous fiasco would be

thankful for the opportunity to step quietly into oblivion. William

Paterson, however, did not choose the easy road, and he lived to do great

things for the country that had treated him so scurvily. He went back to

England, at the turn of the century, faced the King, and made such a

favourable impression that he was asked to put his ideas about the national

finances into writing. This he did, suggesting, among other reforms, the

provision of interest for the national debts, rules for regulating the

treasury and the exchequer so that internal frauds would be impossible, and

last, but not least, the complete union of England and Scotland.

It was agreed at the time

that Paterson was the man who convinced King William that the union of the

two countries would be an achievement of statecraft. He was also

acknowledged to be the genius behind Walpole's famous financial reforms,

particularly the "Walpole Sinking Fund", and the sound and comprehensive

scheme of 1717 for the consolidation and conversion of the National Debt.

When Parliamentary Union became a reality, he went back to Scotland, stood

as a Member of Parliament in Dumfriesshire—where nearly every well-to-do

family had been ruined by the Darien Scheme and where the Union had been

stubbornly opposed—and was elected! The fact has been cited as a great

tribute to Paterson's character; more likely, it simply reflects the fact

that the political machines of those days rode roughshod over the public.

They still do, in rural Scotland.

The next Scotsman to cause a

noticeable stir in London's financial circles was John Law, who was born in

Edinburgh in the year 1671. He became a notable swordsman and tennis-player,

but he had a flair for high finance and headed for London. There he

maintained himself, somewhat precariously, by gambling. He was described, at

this time, as a man "nicely expert in all manner of debaucheries". As a

result of his skill at cards he was challenged to a duel, and as a result of

the duel he found himself charged with murder. He was tried at the Old

Bailey, found guilty, and sentenced to death on 20th April, 1694.

That finished John Law's

financial career in London—but it did not finish his career. He escaped from

prison and disappeared. The following advertisement, published in the London

Gazette of 7th January, 1695, purported to describe him:

Captain John Law, a

Scotchman, lately a prisoner in the King's Bench for murther, aged 26, a

very tall, black, lean man, well-shaped, above six feet high, large

pock-holes in his face, big high nosed, speaks broad and loud, made his

escape from the said prison. Whoever secures him, so as he may be delivered

at the said prison, shall have fifty pounds paid immediately by the marshall

of the King's Bench.

That was probably not an

accurate description of Law, but it was accurate enough to make the reward

for his recapture seem inadequate. Obviously, he was not the sort of man to

be carelessly challenged in the dark, and as nobody did challenge him, he

made his way to France. There he vanished, but not for long, for within two

years he was Comptroller-General of the finances of the Republic, under the

famous Colbert. It was really a pity that England lost the services of this

Scot, for he was a brilliant financier, and one of the few men who

understood the intricate and secretive banking system that had made

Amsterdam the financial capital of Europe.

Law's death in 1729 marked

the end of a period of dangerous national financing and reckless

speculations on the part of the public. A series of protracted booms in the

stocks of vast foreign trading companies had collapsed; those who had had

their greedy fingers burned were, as always, demanding this safeguard and

that for private investors; Cabinet Ministers had to be exceedingly

cautious, and the country settled down to a quieter but sounder routine. We

do not hear of dazzling financiers and daring stock-jobbers for a while, but

the country was being developed rapidly by engineers, inventors, and

hard-working industrialists; and, in Scotland, a system of finance was being

built that supported and developed the new industrialism.

In point of fact, one of the

reasons for the Scots' ascendancy in English business is to be found in the

banking system of Scotland. There were no banks worthy of the name in the

country prior to 1695, and the money-changing and storing was done by

tradesmen. In 1695, however, with the support of William, Prince of Orange,

and the old Scottish Parliament, the Bank of Scotland was incorporated, with

an initial capital of £100,000 sterling, which was doubled in a few years.

The Bank of Scotland issued its first notes in 1704.

Other banks were established.

The Royal Bank of Scotland was formed in 1727, largely for the purpose of

handling "the Equivalent". With £248,550 of this English money to work with,

the Scots entrusted with its distribution formed themselves into a company

and established the Royal Bank.

With the establishment of

these two banks, these islands saw the first financial war that ever rocked

our economic structure. "The New Bank" proceeded to kill the "Auld Bank" by

the simple but deadly process of surreptitiously buying up its notes. By the

year 1730 the Bank of Scotland was in deep water, and to keep afloat it

resorted to the desperate expedient of issuing new five-pound notes, payable

on demand, or six months after being presented, but with interest at the

high rate of 5 per cent. Two years later it was obliged to issue one-pound

notes on the same terms. The insane war ended, as most wars do, when both

the combatants had wearied themselves to the point of exhaustion, and soon

afterwards the Royal Bank felt that it had been victorious when its capital

was raised to the same amount as that of its pioneer competitor—the

staggering sum of £1,500,000 sterling!

In the meantime, the linen

industry of Scotland was developing, and, largely to foster it, the British

Linen Company was incorporated as a bank in 1746. with a capital of

£100,000.

Such were the beginnings of

banking in Scotland; but from these modest establishments was built up a

system of banks and a system of banking that has served, and still serves

for that matter, as a model that the world might well copy. The first and

foremost reason for this is that Scottish banks have always been in close

personal contact with their customers. Open an account with a Scottish bank,

and you may rest assured that you are not merely a walking number, carrying

a bank-book. You are noticed. Quietly, without noticeable prying, your

character is shrewdly assessed, your financial resources and possibilities

gauged. In a small country like Scotland it is not difficult for a bank

manager to get a reasonably accurate focus on the backgrounds of his

customers. The value of the knowledge goes without saying.

In the second place, the

Scottish bankers led the world, and still lead the world, in the matter of

ingenuity of money management. Their system of paper currency has never been

surpassed for efficiency, and indeed it has been copied in England and in

nearly every other country in the world. This sound elasticity, backed by

knowledge and caution, had the result of establishing scientific systems of

credits in Scotland long before England evolved such schemes. The first cash

credit system was established as far back as 1729. It evolved in the mind of

an Edinburgh shopkeeper, and he proposed that he would make up debts

periodically if he got loans of accommodation.

The system worked, and by the

year 1826 there were ten thousand cash credits in Scotland, ranging from

£100 to £5000. When Benjamin Franklin, the great American philosopher,

recommended his scheme to advance loans to small tradesmen who were

beginning in business, he was surprised to learn that such a scheme had been

in successful operation in Scotland for half a century before he mooted his.

Scotland, in fact, had not much to learn about the art of handling money.

Her banks were models of efficiency, and they drew to them, from the first,

the able young men of the country, for in Scotland in those days—as indeed

in the present— the son of a tradesman seldom followed the occupation of his

sire. He aimed for what are termed, probably erroneously, "the higher

professions". The system has made many indifferent preachers out of lads who

would have made good farmers, but on the whole it has drawn brains and

character to professions such as banking.

The success of Scottish

banks, from the beginning, exerted a strong influence on the English banking

system, so much so that when the District Bank was opened at Manchester

about 1820, its management was modelled on the Scottish system, and to make

sure that the system was carried out, a Scotsman was installed as manager.

At that time Scotsmen were in demand in England as bank managers, for the

success of Scotland's paper money had been noted, and whatever Englishmen

may have thought about the Scottish race in general, they were quick to

recognize that its bankers were men of sound training and splendid

character. [England has continued to strengthen her great financial

institutions by enlisting the skill and judgment of Scots. Sir John Gordon

Nairne, Kt., a native of Kirkcudbrightshire, was one of the ablest directors

and comptrollers the Bank of England has ever had. Mr. Kenneth Graham,

author of The Golden Age, was secretary of the Bank of England for many

years, and in his day the governor, chief cashier, and butler were all

Scots! Sir Charles Stewart Addis, born in Edinburgh, was a director of the

Bank of England, and was also president of the Institute of Bankers,

1921-1923. Another able Scottish director of the Bank of England was Sir

Andrew Rae Duncan. Other Scots who have distinguished themselves in the

financial life of England are: Sir William Carruthers, director of Barclays

Bank, Ltd., and vice-president of the Council of the Institute of Bankers;

Sir John Ferguson, president of the Institute of Bankers, 1925-1927; Sir

Robert Home, ex-Chancellor of the Exchequer, and now chairman of the Great

Western Railway; Mr. John F. Darling, for many years a director of the

Midland Bank; and Lord Amulree, whose latest achievement was the financial

rehabilitation of Newfoundland.]

It is a fact that, between

1704 and 1830, there was not one panic or bank-run in Scotland. In England,

on the other hand, the Bank of England was in such a desperate plight in the

early part of the nineteenth century that it was reduced to the necessity of

protracting cash payments by counting out sixpences!

The Bank of England was not

the only enduring financial institution that was given to England by a

Scotsman. The founder of the Savings Bank, as we know it to-day, was the

Rev. Dr. Henry Duncan, who, like

William Paterson, was a native of Dumfriesshire. Dr. Duncan was minister in

the parish of Ruthwell. He was struck with the good which would be

accomplished in his parish if some scheme could be devised to encourage his

parishioners to save their money systematically, and with that idea in his

head drew up a scheme in May of the year 1810 and put it into operation. To

make the habit of thrift permanent, the Governor of this tiny savings bank

had this quaint clause in his first draft of rules: "Every depositor must

lodge to the amount of four shillings at least within the year, under the

penalty of one shilling." He also drew up this rule, and made it work :

"Interest at the rate of 5 per cent is allowed to every depositor who

continues a member of the bank for three years, but such as withdraw the

whole of their deposits before that period receive only 4 per cent."

There was to be no nonsense

about this pioneer savings bank. Depositors had to support it—or get out

with a loss. They did not get out. In the first year of operation the

deposits—in a poor little agricultural parish, remember!—amounted to £151.

In the second year they had increased to £176, in the third year there was a

further increase to £241, and at the end of the fourth year the bank was the

guardian of the vast sum of £922! The minister had made a discovery that was

destined to bring out the amazing strength of Great Britain in years to

come—he had demonstrated that the real wealth of this country is in the

hands of the poor people. A glorious paradox!

The following notice appeared

on the balance-sheet of the bank for the year ending 31st May, 1826.

The general meeting of the

Ruthwell Parish Bank takes place at Ruthwell Church on the first Saturday of

August, at six o'clock in the afternoon, when it is expected there will be a

full attendance, to receive new vouchers, elect office-bearers for the

ensuing year, etc. Each member who is not present at the annual meeting,

either personally or by proxy, incurs a fine of sixpence.

The annual meetings, needless

to add, were well attended.

From this tiny savings bank

of Dumfriesshire grew the modern system of savings banks. Liverpool

established a system in 1815, Manchester followed with a system in 1818, and

other savings banks, all modelled on the principle of the one started by the

Dumfriesshire minister, began to open up all over England, tapping a new and

vast source of national wealth. In 1844 there were 577 savings banks in the

United Kingdom, and they had on deposit £30,000,000—the savings of a million

obscure workers.

In the year 1861 another

distinguished Scotsman, William Ewart Gladstone, Chancellor of the

Exchequer, added tremendous strength to the country's financial fabric by

putting through the Post Office Savings Bank Act. England had been shown

where her real financial reserves lay, and the proof of it was seen during

the great storm that beat upon these shores between 1914 and 1918, and

later, in 1933, when the world gasped at the phenomenon of our war-weary

country converting more than £2,000,000,000 of Five per cent War Loan to a

three and a half per cent basis in a few hours.

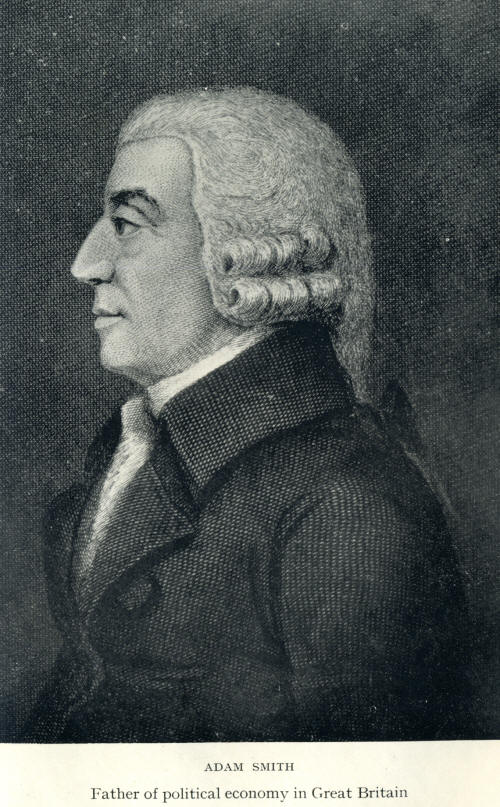

In considering the influence

which Scotsmen have exerted on the commercial and financial development of

England, it is impossible to overlook the man who analysed the new

commercial status of England and gave it a meaning and purpose that made

Great Britain the supreme trading nation of the world. We refer, of course,

to Adam Smith, the father of political economy in this country.

This profound thinker was

born on 5th June, 1723, at Kirkcaldy. Thoughtful, but not particularly

brilliant as a boy, he was advised by some well-meaning idiot to enter the

English Church. He had a narrow escape too, for he went on to Balliol

College, Oxford, in 1740, studied there long enough to display a genius for

mathematics and a quiet contempt for the logic of Aristotle, which pervaded

Oxford, and to make up his mind that a pulpit was scarcely a suitable

rostrum for Adam Smith. He went back to Edinburgh, became friendly with

David Hume, looked round for a position, and eventually was appointed

Professor of Logic at Glasgow University in 1751. From that modest pedestal

in the seat of learning he stepped up to the chair of Moral Philosophy, and

it was while in this position that he turned his mind to the scientific

study of the politico-economic system of Great Britain. He did not rush into

print with his profound conclusions, for it was not until 1776 that he

published his Wealth of Nations, but when that book did appear it changed

England, bringing it into economic and political harmony with the industrial

revolution brought about by that other Scot from Glasgow— James Watt.

Adam Smith tackled the

involved problems of British and world economics with the sure skill of

instinctive knowledge. He did not probe here and there, as so many

pseudo-economists are doing to-day, and then base impressive but hazy

conclusions on these random thrusts. He did not need to make thrusts. He was

sure of himself, and analysed the political and economic problem that had

grown up in England with the same skill that one sees in the surgeon who

thoroughly understands the case which comes under his knife. Thus, instead

of involved and hazy economic theories, such as have inundated us during the

past few years, Adam Smith reduced the complicated mysteries of

international economics to plain understandable formulae and equations. With

the deceiving ease of a master, he explained the sources of the world's

vastly increased wealth, showed that real wealth consisted, not of coined

metals but of plentiful supplies of ordinary human necessities,

conveniences, and luxuries, and that labour was the only source of this

wealth.

It is the maxim of every

prudent master of a family [he wrote] never to attempt to make at home what

it will cost him more to make than buy. The tailor does not attempt to make

his own shoes, but buys them of the shoemaker; the shoemaker does not

attempt to make his own clothes, but employs a tailor. The farmer attempts

to make neither the one nor the other, but employs those different

artificers, all of whom find it for their interest to employ their whole

industry in a way in which they have some advantage over their neighbours,

and to purchase with a part of its produce whatever else they have occasion

for. What is prudent for a family, is prudent for a great kingdom. If a

foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can

make it, better buy it of them with some part of the produce of our own

industry, employed in a way in which we have some advantage."

Thus Adam Smith in 1776. His

profound analysis of Great Britain's economic system was translated into

every European language, and was debated in a thousand seats of learning.

Its effect upon England was profound. Politicians and manufacturers and

workmen saw a clear picture of the country's complicated condition, brought

about by the mechanical age. They saw Great Britain in her future

relationship to the world.

Adam Smith completed the

Wealth of Nations in 1776 [wrote Walter Bagehot, the noted English

economist, in 1896], and our English political economy is therefore just a

hundred years old. In that time it has had a wonderful effect. The life of

almost everyone in England—perhaps of everyone—is different and better in

consequence of it. The whole commercial policy of the country is not so much

founded on it as instinct with it. Ideas which are paradoxes everywhere else

in the world are accepted axioms here as results of it. No other form of

political philosophy has ever had one thousandth part of the influence on

us; its teachings have settled down into the common sense of the nation, and

have become irreversible.

There was only one conclusion

possible after studying Adam Smith's theories—industrialized England should

march forward under the banner of Free Trade. That is what she did, and

before the author of The Wealth of Nations died he had caught a glimpse of

the glorious destiny of these islands under a free government and free

ports. It was only a glimpse. Adam Smith himself could scarcely have

visualized the astounding wealth, power, and cultural development that

followed the adoption of his political economy. Indeed, the country itself

scarcely realized how strong it had become until its financial and

industrial fabric were tested by the Great War. Then, in good truth, the

wealth of nations seemed to be centred in Great Britain. The picture had

been clouded during the past few years. A confused and paternal Government,

with costly tariffs and quotas paid for by the taxpayers, has departed from

the sound doctrine laid down in The Wealth of Nations, but in our heart of

hearts we know that the measure of this country's commercial strength is its

capacity to buy and sell in free markets—and that the other road leads to

paralysis.

In his delightful delineation

of Scottish character, Mr. T. W. H. Crosland hinted darkly that the day of

the Scot in England's offices of business was waning:

Brilliancy and imagination

are nowadays just as much wanted in business as in any other department of

life [he wrote]. Tact and a reasonably decent feeling for your fellow man

are also wanted. Your Scot on his own showing does not possess these

qualities. He even goes so far as to disdain them and to assure you that

they are not consistent with "force of character" and "rugged independence".

The moral is obvious, and I should not be surprised if English employers of

labour have not already begun to take it to heart.

The sombre prophecy has not

come true, probably because of the obvious difficulty of discharging a Scot

in England when he happens to be the managing director! Business is

business, and the Scot generally goes a long way in English business simply

because he is equipped for business. He has been trained to be diligent and

thoroughgoing, and these are priceless virtues in the world of business.

There is a tradition that the Scot, when vested with authority, becomes a

bully. Some do. We have been bullied by Scottish sub-editors, but in every

case the sub-editors were terrorized by managing-editors who were not Scots,

and when subjected to pressure from above, a Scottish sub-editor is a

pitiable object. We remember being sent out by one of them to interview the

famous American airman, Colonel Charles Lindbergh. It was to be something

special. The "big chief" had nominated us for the job. Two motor-cars were

placed at our disposal, and a squad of dizzy young reporters and hard-boiled

photographers. They were to run down the game; our job was to shoot it at

close range. Just before the newspaper went to press we discovered that

somebody had gone off at half-cock. Lindbergh wasn't even in the country. We

broke the sad news to the Scottish sub-editor, adding a few comments.

"He should have been here!"

he wailed, and with a baleful glance at us straightened his tie and went

into the "big chief's" office to be slapped.

All over England, in high

places and low, Scots are battling for their daily bread, or scheming to

keep caviare on their tables. On the whole, they are not a bad lot, but they

suffer, in the eyes of the Englishman, because the occasional Mungo appears

among them. When an Englishmen meets a man like Mungo, he is suspicious ever

afterwards of anybody who has a Scottish accent. You cannot blame him.

Mungo was a stupid dolt of a

lad. He was brought up on a poor farm and sent out into the world with a

moist nose and a voice that suggested adenoids. At school we all knew that

he was an arrant coward, afraid of a fight but ready to hug himself with

delight if he could induce smaller lads to bash one another.

We were thrown together after

we left school. None of us had much money to spend in those days, but

Mungo's meanness began to dawn upon us. He would not spend a penny for a

newspaper, but he read them every day—by borrowing them from his friends. He

walked out into the country one day to see some people he knew—he could have

gone by train, but the fare amounted to three-and-sixpence— and when he

reached his destination the people were away at the seaside. Mungo walked

back home. His feet were blistered, and he was weak with hunger. When we sat

down at the boarding-house table that evening, he ate everything in sight,

including the mustard pickles, which had been an ornament on the table for

weeks. The landlady, a decent old dame, did not let it pass unnoticed. "Did

ye hear whut she sayed?" complained Mungo, when we got upstairs. "Jingo! I

hadna eaten a thing since breakfast!" "Why didn't you buy a lunch in one of

the villages?" we asked. Mungo made creaking sounds like a rusty door.

"I wusna gaun tae spend my money like that!" he

protested sulkily. "No' when I'm paying for ma board here. Nae fear! Note

me!"

Poor old Mungo went through

life like that. He slaved away in London for several years with a big

commercial concern, and was eventually sent to the tropics as an inspector

of trading posts owned by his London employers. He was meaner than ever

under tropical skies, hounded the men under him, and added to his company's

profits. His manager, a genial Englishman who was hit periodically by

malaria, was suddenly discharged. Of course Mungo had nothing to do with

that—beyond indicating in private reports to the Scottish manager at home,

as he told piously, that things were a bit slack. Mungo was put into the

Englishman's place. He was too penurious to engage native servants, and

lived like a dog. Even the malaria wouldn't touch him. He drove a number of

public school boys back to England, and replaced them with raw young

snivelling Scots, whom he bullied.

Unfortunately, one of the

Scottish recruits happened to be a Glasgow chap with a short temper and

considerable courage. Primed with whisky one night, he walked up to Mungo's

bungalow and invited the general manager to "put them up". Not having any

servants around, Mungo was in a bad corner. He tried to threaten the

intruder. It didn't work. Then he became placatory. That didn't work either.

The upshot of the conference was that the Glasgow lad was discharged, but

Mungo remained in his bungalow for several days.

He was more severe with his

staff after that, but his number was up. The Glasgow man's uncle, it turned

out, was a man of some importance, and he had gone into action after he

heard the nephew's story. Mungo's services were eventually dispensed with,

and he came back to Scotland and bought a home in the country. He died

several years ago, and his neighbours, with the sly malice that one

encounters sometimes in rural communities in Scotland, said that the cause

of death was malnutrition. Poor old Mungo didn't die of hunger, although, as

he grew older, he reduced his diet to the minimum. I think he gave up the

ghost because he had failed to discover how to live without spending money.

Life had lost its meaning. He left an astonishingly large amount of cash,

and it started a frightful row among the relatives who survived him.

It is an unfortunate fact

that Scots of Mungo's type go into business, and it is equally unfortunate

that in business their unsocial characteristics are apt to be mistaken for

virtues. The result is that the Mungos get along—up to a certain point. They

never become mellow, but when success is no longer in doubt, they make

sickly attempts to appear civilized. They will tell you proudly about the

harrrd strrruggle they have had, and how proud they are to be Scots, and, if

they are not firmly checked, they will go on and tell you the execrable

story about the Scot who spent a week in London on business, and who got

back to Glasgow without having met an Englishman. The Mungos are too keen

and single-minded to be crowded out of England's business, but they should

be ignored by all good Scots. Above all, they should never be permitted to

hold office in Caledonian societies.

We had just got nicely

started with a description of the best type of Scot found in English

business, when our eye was caught by an obituary notice in The Times of 5th

April, 1934. We had never heard of the Aberdonian whose death it recorded,

but it is so far ahead of anything we could have written that we append it

proudly, without a word of comment:

Mr. Henry Walter Thomson, who

died on Sunday, after a long illness, at his country home, The Warren,

Woodham Walter, Essex, at the age of 78, was a member of a large Aberdeen

family which had played a worthy part in the life of the past two

generations.

Several of his brothers were

pioneers in their respective spheres. George founded the African Banking

Corporation, which some years ago was absorbed by the Standard Bank of South

Africa. Peter built up the fortunes of the Borneo Company, and was for some

time its managing director. Alexander started the Stock Exchange firm of

Alexander Thomson and Co., which was the first to deal in Colonial

Government securities. Three other brothers were at one time members of the

Stock Exchange, of whom the best known was Henry. In 1887 he joined his

brother's firm, of which he was senior partner at the time of his death.

Reference to the family would be incomplete without the inclusion of one

other brother, the late Mr. Leslie Thomson, the water-colour artist.

While for some years prior to

the seizure that left him an invalid he was content to leave the actual work

of dealing to his younger partners, Henry Thomson to the end took the

closest interest in the business of his firm, and on account of his wide

knowledge and ripe experience his opinions on finance, and especially the

finances of the Overseas Dominions, were freely sought by fellow members of

the Stock Exchange. One other business activity of his was the directorship,

dating from its inception, of the Pahang Corporation. Together with his

brothers he was instrumental some years ago in preserving this great

tin-mine in British hands when there was a real danger of its passing into

the possession of Chinese mining interests.

Mr. Thomson's business

engagements did not preclude him from doing a great deal of charitable work.

Service to others, indeed, seemed to be the motto of his daily life. For

over thirty years—in fact, until he was compelled to retire on medical

grounds—he was on the committee of St. Thomas's Hospital, of which he was

one of the governors. He was also a life governor and member of the finance

committee of Christ's Hospital, and a member of the committee of the

Scottish Corporation, and in addition took a keen interest in the Royal

Caledonian School and the Foundling Hospital. To the time he so ungrudgingly

gave in the interests of these organizations he supplemented the help of an

ever-open purse. It might truly be said of him that to any deserving case of

need he never turned a deaf ear.

He had that true charity of

disposition that made him incapable of cherishing or invoking enmity. In the

office over which he presided, virtually the whole staff have grown up in

the firm's service, and all the present partners began business life in the

office of the firm and were gradually admitted by their chiefs. In

meditating on the characters of Henry Thomson and his brother Alexander—for

although the latter died nearly twelve years ago, it seems impossible to

separate them—one reminded forcibly of the Cheerybles immortalized by

Dickens. Each possessed in rare degree the milk of human kindness, and,

moreover, there was about the two brothers just that touch of mid-Victorian

manners that Dickens so inimitably pictured. To the last both brothers

practised a number of those outward courtesies that virtually went out with

the incoming of the telephone and the motor-car. It was, for instance, a

habit of theirs, never missed, before leaving the office each day to shake

hands with each member of the staff, and the habit was one that fitly

symbolized the relationship between employer and employed.