The assumption of the throne of England by James I marked

the commencement of the first tide of emigration which flowed from Scotland

towards London. Poverty and distress were acute in the country he had

reigned over for thirty-five years, and it is not surprising, therefore,

that when he set out for London on 5th April, 1603, his ponderous equipage

was followed, at a discreet distance, by a long train of penniless but

hopeful Scottish adventurers. The Scots had found the road to England, and

they never allowed it to become grass-grown.

James did not enter his new kingdom humbly. He was a

Stuart and the son of the most beautiful and entrancing Queen that Europe

has ever known. He had ruled the turbulent Scots for a third of a century,

and had a good opinion of himself and his countrymen. He has been painted,

by successive historians, as a clown and a fool; but his record, as we shall

see, indicates that he had more sagacity than his new subjects gave him

credit for, and at least as much culture as the Tudor boors who preceded him

on the English throne.

He had time to think about the future on the way south,

for the journey occupied more than a month. Day after day the clumsy

procession floundered slowly over roads that were little better than

ditches. Some of the mud was churned up by curious and ambitious Englishmen,

who ploughed northward to meet the new monarch. At Theobalds, where a halt

of four days was made in the first week of May, hundreds of fore-handed

English nobles and squires surrounded the royal cavalcade. They did not

understand the terse, sharp-tongued man who had come south to rule over

them; but he seemed to understand them pretty well, for he proceeded to

distribute knighthoods with a prodigality that has never been equalled.

There were two hundred and thirty-seven new knights in England by the time

he reached Stamford Hill, and if an outbreak of plague had not prevented the

stately entry into London which had been planned, as many more empty but

coveted honours would have been distributed by the kingly hand.

There were murmurs of protest

from the Scottish courtiers as these titles were flung about so recklessly,

but the King offset his seeming partiality towards his new subjects as soon

as he assumed the throne by appointing six of his Scottish favourites

members of the Privy Council. He was shrewd enough to see that he would be

safer with Scottish advisers around him than with Englishmen, whose mincing

language he could scarcely understand. He even took Scottish medical

advisers south with him, for Gilbert Primrose acted as his sergeant-surgeon,

and John Naysmyth filled the position of royal herbalist. Both these

Scottish men of medicine served the King until he died, and they may be said

to be the first of the long and almost unbroken line of Scottish physicians

and surgeons who have served the royal household throughout the succeeding

centuries.

It is a pity that King James

was not so happy in his choice of political advisers, for there is no

disguising the fact that the small Scottish claque that surrounded him

contained a good many dolts and a few dangerous scoundrels. The most

notorious of them all was Robert Carr, or Ker, who followed his royal master

to London as a page. Carr was an ignorant coxcomb, but he was ambitious and

had a way with him. He ingratiated himself to such an extent with the King

that he woke up one morning to find himself bearing the titles of Viscount

Rochester and Earl of Somerset. Carr continued to soar, until he married the

divorced Lady Essex. Soon after that event he became involved in the

poisoning of Sir Thomas Overbury. Unable to clear himself of the charge of

murder, he threw himself upon the mercy of the King. James, however, had to

draw the line somewhere with his favourites, and his memory of Scottish

assassins and would-be assassins was too vivid to enable him to be lenient

with a murderer found in his own Court. Carr pleaded, like the poltroon he

was, but the King was adamant, and the Earl of Somerset was seen no more in

the royal household.

James Stuart gave England a

shock. That country had not been accustomed to handsome rulers, but the

physical peculiarities of the new King gave him a monstrous aspect. He had a

huge head, a lumpy body that was swathed deeply in a cocoon of dirty

quilting, and rickety legs that did not seem equal to the task of supporting

his body when he walked.

His tongue was too big for

his mouth, saliva dribbled from the corners of his lips, and when he talked

it was with a raucous Scottish accent that baffled the majority of his

courtiers. His belly was padded deeply because, ever after the attempt of

the sons of the Earl of Gowrie to stab him to death at Perth, he was haunted

by the fear that some other disgruntled noble would attempt to knife him.

The chilly feeling that lay in his bowels need not be attributed to

cowardice ; any man who had lived as long as he had among the assassins who

surrounded the Scottish Court was morally entitled to all the quilting his

stomach would stand.

That he was uncouth,

clownish, and stubborn, combining some of the wrong-headedness of his proud

mother with the timidity and physical weaknesses of his degenerate sire,

cannot be denied; but withal, he was the first educated monarch that England

had seen. His mind had been crammed by the erudite Buchanan, and while his

conversation indicated that much of the learning he had absorbed lay raw and

undigested in his mind, he was a scholarly figure in comparison with the

illiterate numskulls who flittered sneeringly about his grotesque Court. He

has suffered at the hands of historians because his character has been

judged by the memoirs of men like Sir John Harington and James Howell, both

of whom deal with trivial matters in a trivial way. Harington's Nugae

Antiquae and Howell's Epistolae Ho-Elianae, in their original editions, lie

before us as we write, and although we have read their dreary pages

dutifully, they leave no impression upon our mind except the vague feeling

that the Court of King James was one of foolishness and vulgarity, and that

courtiers are gossips rather than historians.

Another book, published in

1616, entitled The Workes of the Most High and Mightie Prince James, lies

before us. It was written by the King himself, and containing, as it does,

his considered views on questions ranging from the use of tobacco to the

rights of kings, it gives us a much better opportunity to assess his

mentality and character.

Let us turn the yellowed

pages. Here is a sonnet, to "His Dearest Sonne Henry, the Prince":

God gives not Kings the stile

of Gods in vaine,

For on His Throne His Scepter doe diey swey:

And as their subjects ought them to obey,

So Kings should feare and serve their God againe:

If then ye would enjoy a happie raigne,

Observe the Statutes of your Heavenly King,

And from His Law, make all your Lawes to spring:

Since his Lieutenant here ye should remaine,

Reward the just, be stedfast, true, and plaine,

Represse the proud, maintayning aye the right,

Walke alwayes so, as ever in His sight,

Who guardes the godly, plaguing the prophane:

And so ye shall in princely vertues shine,

Resembling right your mighty King Divine.

Whatever criticism may be

levelled at these words as poetry, they are certainly not the words of a

fool or a profligate. They stick in one's mind, leaving the conviction that

the royal composer was a man who had serious and sincere ideas of kingship,

founder advice, surely, was never given by King to Prince.

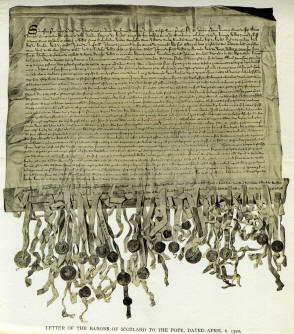

Letter of the Barons of

Scotland to the Pope April 6, 1320

We read on. Here is his

lengthy "Defense of the Right of Kings". We may disagree with his views on

that subject, but consider this excerpt from his dissertation, purely as

terse, sardonic argument and the telling use of words:

But I have been ever of this

mind, that when my goods are at no man's command or disposing but mine own,

then they are truly and certainly mine own. It may be this error is grown

upon me and other Princes for lacke of brains: whereupon it may be feared,

or at least conjectured, the Pope means to shave our crowns, and thrust us

into some cloister, there to hold rank in the brotherhood of good King

Childeric. For as much then as my dull capacity does not serve me to reach

or comprehend the pith of this admirable reason, I have thought good to seek

and to use the instructions of old and learned experience, which teacheth no

such matter; by name, that civil wars and fearful perturbations of State in

any nation of the world, have at any time grown from this faithful credulity

of subjects, that Popes in right have no power to wrest and lift Kings out

of their dignities and possessions. On the other side, by establishing the

contrary maxims, to yoke and hamper the people with Pontifical tyranny, what

rebellious troubles and strifes, what extreme desolations hath England been

forced to feare and feel, in the reigne of my predecessors, Henry

II, John, and Henrie III ? These be the maxims and

principles, which under the Emperor Henrie IV and

Frederick the ist, made all Europe flow with channels and streams of blood,

like a river with water, while the Saracens by their incursions and

victories overflowed, and in a manner drowned, the honour of the Christian

name in the East. These be the maxims and principles, which made way for the

wars of the last league into France, by which the very bowels of that most

famous and flourishing kingdom were set on such a combustion that France

herself was brought within two fingers' breadth of bondage to another

Nation, and the death of her two last Kings most villainously and

traitorously accomplished. The Lord Cardinall then giving these diabolical

maximes for means to secure the life and estate of Kings, speaketh as if he

would give men counsel to dry themselves in the river, when they come as wet

as a water spaniel out of a pond; or to warm themselves by the light of the

moone, when they are stark-naked, and well-near frozen to death. [King James

was accustomed to crossing swords with religious bigots. During the early

years of his reign in Scotland the rudeness of the clergy towards the Crown

was notorious. Inspired by the hectoring Knox, they harangued King James

from the pulpit in St. Giles' Church, but he used to make sardonic and

disconcerting retorts from the Royal Gallery.]

Huntingdon called the author

of these words "the wisest fool in Christendom", which merely adds point to

the French diction, that the epigram is a device used by weak men against

those that are stronger.

Prior to his assumption of

the combined thrones, literature in England was a despised and degraded art.

The majority of the literary figures of the period were little better than

mendicants, and none of them had ever dreamed of such a thing as royal

patronage. King James was the first occupant of the English throne to

encourage the art of letters. It is to his credit that he saw something of

national value in the writings of men like Shakespeare, Bacon, [Howell, in

his Familiar Letters, Domeftic and Forren, reveals the critical mind of King

James in recounting an amusing discussion that took place between the King

and Sir Francis Bacon regarding M. Cadenet, who had recently arrived in

London as the Ambassador from France. The King asked Bacon what he thought

of the Frenchman. "He is a tall, proper man," replied Bacon. "Aye," said the

King, "but what think you of his headpiece? Is he a proper man for the

office of an Ambassador?" "Sir," replied Bacon, "tall men are like high

houses of four or five stories, wherein commonly the uppermost room is worst

furnished!"] Spenser, and Jonson, [Ben Jonson (1573-1637), whose lovely

poem, "Drink to me only with thine eyes", has come down through the

centuries with undiminished charm, was a Scot. His grandfather was a native

of Annandale, and belonged to the powerful Johnstone family of that

district.] and that he gave kingly encouragement to these creative giants

who were laying down, in such dreary surroundings, the enduring foundations

of our literature and our drama.

There were other features of

this greatly ridiculed monarch which made him symbolize the Scottish genius

that was destined to play its part in England's development. He was a

pacifist. He desired peace, not only between England and her hereditary

enemy in the north, but also between England and the foreign nations with

whom she had been wrangling at such great cost. It certainly cannot be

argued that James Stuart was afraid of the clanging of arms, but he brought

to English statecraft, for the first time, a sense of the shrewdness of

calculated pacifism. We shall discern, in the Scotsmen who were destined to

lead England in the centuries that followed, this same spirit—a tendency to

calculate the cost of war, a cautious respect for the rights of other

nations and a desire to keep a bellicose race out of costly mischief.

There was nothing very timid

in the method he adopted in dealing with the internal troubles of the

country he had been called upon to rule. One of his first tasks was to put

the gloomy and stubborn Puritans in their places. He had noticed them when,

in Lancashire, they prohibited recreation on Sundays, after church, and

issued a declaration setting forth that the harsh restriction barreth the

common and meaner sort of people from using such exercises as may make their

bodies more able for war, when we or our successors shall have occasion to

use them; and in place thereof sets up filthy tiplings and drunkenness, and

breeds a number of idle and discontented speeches in their ale-houses ; for

when shall the common people have leave to exercise, if not upon the Sunday

and holidays, seeing they must apply their labour, and win their living, in

all working days.

No prelate could have put the

thing more succinctly, but the Puritans were so persistent that James

decided to rid the country, once and for all, of the trouble-makers. He

accomplished that at the Hampton Court Conference, and out of that rowdy

scene came the Authorized Version of the English Bible, still printed with

the inscription: "To the Most High and Mighty Prince James". Pious

historians have blamed him for sending the Pilgrim Fathers to America, but

the hegira of these refractory zealots was probably a good thing for

England, for the exiles soon developed into an insufferable sect in New

England. Indeed, traces of their long regime of harsh piety and

self-interest may still be seen in the United States, in numerous "Blue

Laws" that no enlightened nation would tolerate, in mouldering stocks and

whipping-posts, and in systems of State government, notably in Maine and

Massachusetts, which still retain traces of the selfish rapacity of these

gentle people.

Towards the Catholics the

attitude of James was one of tolerance, but instead of showing their

appreciation, they tried to blow him up, and nearly succeeded. It is no

wonder that from the date of the Gunpowder Plot onward he displayed less

patience with religious factions.

He proceeded on the

assumption that he was the ruler of England and Scotland by divine right.

His first parliament made him slobber and curse, for after meeting five

times it rejected his plan of free trade with Scotland and squashed his

scheme for placing Scotsmen on the same legal footing as Englishmen. The

impasse indicated, surely, that the King had a much clearer conception of

statesmanship than the garrulous obstructionists who sat in Parliament.

His quarrel with the elected

representatives of the people became more bitter as the years passed.

Between 1611 and 1620 there was only one session of parliament—"the Addled

Parliament" of 1614— and even that brief display of pomp and popular

authority made James swear heartily in broad Scotch. "As it is atheism and

blasphemy to dispute what God can do," he exclaimed in the Star Chamber, "so

it is presumption and a high contempt in a subject to dispute what a King

can do, or to say that a King cannot do this or that."

In these enlightened times,

of course, such a declaration would amuse the public, yet the fact remains

that we have seen one country after another brought to chaos by fumbling

parliaments and restored to order and vitality by dictators who have assumed

more power than King James ever aspired to wield.

He was never stabbed while he

ruled the English, but his reputation has been stabbed again and again by

historians in the traditional Oxford manner. [The tradition is that he was

not held in high esteem in Scotland, but when he visited Edinburgh in 1617,

the Town Clerk delivered an address in which he declared fervently that "the

very hills and groves, accustomed before to be refreshed with the dew of

your Majesty's presence, and not putting on their wonted apparel, but with

pale looks representing their misery for the departure of their royal King—a

King in heart as upright as David, wise as Solomon, and godlie as Josias"I]

It is well to remember that this grotesque Scot had great difficulties to

contend with. He was desperately short of money, and his pecuniary problems

were aggravated by the Scottish sycophants, debt collectors, and ambitious

scions of noble families who trailed after him into England. Nearly all of

them were penniless, and they formed a besieging army that gave the King no

peace. The ubiquitous debt collectors were the bane of the King's existence

in London. They were constantly intruding upon his royal privacy, presenting

their soiled accounts. So persistent were they, that, to get rid of them and

their irritating claims, James had the following Proclamation issued by the

Lords of the Council :

That in consideration of the

resort of idle persons of low condition forth from His Majesty's Kingdom of

Scotland, to his English Court, filling the same with their suits and

supplications and dishonouring the royal presence with their base, poor, and

beggarly persons, to the disgrace of their country in the estimation of the

English ; these are to prohibit the skippers, masters of vessels, and

others, in every part of Scotland, from bringing such miserable creatures up

to Court, under pain of fine and imprisonment.

The proclamation also

contained this clause:

That such idle suitors are to

be transported back to Scotland at His Majesty's expense, and punished for

their audacity with stripes, stocking, or incarceration, according to their

demerits.

There was also a clause which

made even darker threats against the besieging army of importuning Scots

suitors "who shall be so bold as to approach the Court, under pretext of

seeking payment of old debts due to them by the King, which is, of all kinds

of importunity, most unpleasing to His Majesty".

These stringent measures

against collectors from Scotland did not always have the desired effect, if

we are to believe Sir Walter Scott, and sometimes the modus operandi of the

approach to the royal presence left something to be desired in the way of

diplomacy. Young Lord Nigel was one of the adventurers who followed King

James to London, carrying a supplication on behalf of his father. The actual

presentation of the unpaid bill to His Majesty was left in the hands of

Nigel's Scotch manservant, and the following discussion, which took place in

the home of Master George Heriot, another Scot who had followed the King

south, illustrates the predicament of the royal debtor and the dogged

self-interest of his pursuers.

Master Heriot: "I am given to

understand that you yesterday presented to His Majesty's hand a

supplication, or petition, from this honourable lord your master."

Moniplies: "Troth, there's

nae gainsaying that, sir—there were enow to see it besides me."

Master Heriot: "And you

pretend that His Majesty flung it from him with contempt? Take heed, for I

have means of knowing the truth; and you were better up to the neck in the

Nor-Loch, which you like so well, than tell a leasing where His Majesty's

name is concerned."

Moniplies: "There's nae

occasion for lease-making about the matter. His Majesty e'en flung it frae

him as if it had dirtied his fingers."

Master Heriot: "Answer me

this farther question—when you gave your master's petition to His Majesty,

gave you nothing with it?"

Moniplies: "Ou, what should I

give wi' it, ye ken?"

Master Heriot : "That is what

I desire and insist to know."

Moniplies: "Weel, then—I am

not free to say, that maybe I might not just slip into the King's hand a wee

bit sifflication of mine ain, along with my Lord's—just to save His Majesty

trouble—an' that he might consider them baith at ance."

Lord Nigel Oliphant: "A

supplication of your own, you varlet?"

Moniplies: "Ou, dear, ay, my

Lord—puir bodies ha' their bits of sifflications as well as their betters."

Master Heriot: "And pray,

what might your worshipful petition import ? Speak out, sirah, and I will

stand your friend with my Lord."

Moniplies: "It's a lang story

to tell—but the upshot is, that it's a scrape of an auld accompt due to my

father's yestate by Her Majesty the King's maist gracious mother, when she

lived in the Castle, and had sundry providings and furnishings forth to our

booth, whilk nae doubt was an honour to my father to supply, and whilk,

doubtless, it will be a credit to His Majesty to satisfy, as it will be grit

convenience to me to receive the saam."

Lord Nigel Oliphant: "What

string of impertinence is this?"

Moniplies: "Every word as

true as ever John Knox spoke. Here's the bit double of the sifflication—'Humbly

showeth— um-um—His Majesty's maist gracious mother—um-um—justly addebted and

owing the sum of fifteen merks—the compt whereof followeth—twelve nowte's

feet for jellies—ane lamb, being Christmas—ane roasted capin in grease for

the privy chalmer, when my Lord of Bothwell suppit with her grace."

Master Heriot:

"I think, my lord, you can hardly be surprised

that the King gave this petition a brisk reception, and I conclude, Master

Page, that you took care to present your own supplication before your

master's?"

Moniplies: "Troth, I did not.

I thought to have given my Lord's first, as was reason gude, and besides

that, it wad have redd the gate for my ain little bill. But what wi' the

dirdum and confusion, an' the loupin' here and there of the skeigh brute of

a horse, I believe I crammed them baith into his hand cheek-by-jowl—'and

maybe my ain was bunemost."

With such sly, sententious,

and implacable collectors on his trail, it was no wonder that King James led

a hunted life and rebelled against his countrymen. "One would think they had

a mind to squeeze my puddings out, that they may divide the inheritance," he

complained to Master George Heriot. "Ud's death, Geordie, there is not a

loon among them can deliver a supplication as it suld be done in the face of

majesty!"

Master George Heriot, whose

name has already been mentioned, and whose activities in London created

material—not all of it strictly in accordance with facts—for the pen of Sir

Walter Scott, was one of the first Scotsmen to establish himself in business

in London. He was a goldsmith, and was known as "Jingling Geordie". He was a

shrewd, industrious, and generous man, was a competent artisan, and enjoyed

the friendship and confidence of King James. Heriot befriended many of his

less fortunate fellow-countrymen in London, and his house was a rendezvous

for Scots who were waiting patiently for favours at Court. Master Heriot

never looked behind him after he established his business in London, and

that he had not been warped by the doctrines of John Knox is indicated by an

invitation to dinner which he extended to his young compatriot, Lord Nigel.

"I am glad to see you smile,

my lord," says Master George; "and it emboldens me, besides, to bring out a

small request— that you would take a homely dinner with me to-morrow. I

lodge hard by—in Lombard Street. For the cheer, my lord, a mess of white

broth, a fat capon well larded, a dish of beef collops for auld Scotland's

sake, and it may be a cup of right old wine, that was barrelled before

Scotland and England were one nation. Then, for company, one or two of our

own loving countrymen—and maybe my housewife may find out a bonny Scots lass

or so!"

There is no mention of music

in the prandial programme suggested by the pawky George, but it was probably

forthcoming ! Unquestionably, he was a man who knew how to entertain young

blood from Scotland.

Another Scot who followed his

King to London, and who succeeded in business there, was David Ramsay. He

was born in Dalkeith, and blossomed out in the metropolis as a watchmaker

and horologer to the King. He had his little shop in Temple Bar. east of St.

Dunstan's Church, and by skill and frugality managed to become moderately

wealthy. That he enjoyed the royal patronage did not turn David's hard head.

He solicited other business with avidity. When his apprentices were not

occupied with work in the shop, they were out in the street soliciting

customers, with the old cry: "What d'ye lack? What d'ye lack?

Clocks—watches—what d'ye lack?"

David Ramsay had such a

profound admiration for his royal patron, and such a firm belief that a high

destiny awaited him, that he sold clocks and watches on condition that they

need not be paid for until King James sat on the Pope's throne at Rome. That

very un-Scottish proceeding soon involved him in financial difficulties, and

he made an effort to retrieve his fortune by searching for treasure in the

cloister of Westminster Abbey. The treasure was supposed to be buried there,

and the resourceful Ramsay tried to find it at night by using a Mosaical

Rod. The nocturnal search did not produce the desired result, but it

produced a good deal of amusement in London, and the eccentric clockmaker

was regarded as a harmless imbecile:

For he by geometric scale,

Could take the size of pots of ale,

And wisely tell what hour o' th' day,

The clock does strike by algebra.

Truth to tell, however, David

Ramsay was a genius whose experiments were far ahead of his time. When his

name is brought out of the dusty archives of history, it is usually for the

purpose of alluding to the eccentric aspects of his character. The

significant fact that he was one of our very first inventors is seldom

brought to light. Yet between 1618 and 1638 this Scot obtained eight

patents, and the numbers of the first two were five and six respectively,

proof that he was more than a mere pioneer in the movement of Scottish men

of business to London. The wide range of his mind is reflected by the nature

of the patents he secured ; they had to do with ploughing land, fertilizing

barren land, raising water by fire, propelling ships, manufacturing

saltpetre, making tapestry without a loom, refining copper, bleaching wax,

separating gold and silver from the base metals, dyeing fabrics, heating

boilers, kilns for drying and burning bricks and tiles, and smelting and

refining iron by means of coal. The man was a century and a half ahead of

his time. His inventive genius would have found a practical outlet in that

astounding period, to which we shall refer in due course, in which England

was made rich and powerful by Scottish inventors.

We leave David Ramsay among

his clocks and watches. It may be said of him that he was the first Scotsman

who established a business in England, and a very worthy pioneer he was. He

died in 1653, just a year after his son William took his medical degree at

Montpelier. The son, it is worth adding, was appointed Physician-in-Ordinary

to King Charles II, and by gaining that exalted

distinction became the first of the long and almost unbroken line of

Scottish physicians and surgeons who have served the royal household

throughout the centuries.

King James, with all his

faults, had introduced a new vigour to English political life, and had shown

that he was not lacking in statecraft. He had opposed religious fanaticism,

had established important new colonies in Virginia and Nova Scotia, had kept

the English out of wasting wars, had made the Highland Chiefs of Scotland

toe the line of good citizenship by forcing them to report periodically to

the Privy Council, had put the fear of the Lord into the Lowland rowdies who

terrorized the Border country, and had advocated the union of the English

and Scottish Parliaments. He was one of the few Stuart rulers who died in

his bed, but they got at that heavily quilted stomach of his after all, for

Howell, in his diary of 11th December, 1625, writes:

It was my fortune to be on

Sunday was fortnight at Theobalds, when his late Majesty King James departed

this life and went to his last rest. A little before the break of day, he

sent for the Prince, who rose out of his bed and came in his Night-Gown ;

the King seem'd to have som earnest thing to say to him, and so endeavoured

to rouse himself upon his pillow, but his spirits were so spent, that he had

not strength to make his words audible. He died of a Feaver which began with

an Ague, and som Scotch Doctors mutter at a plaster the Countess of

Buckingham applied to the outside of his stomach. There are great

preparations for the Funeral, and ther is a design to buy all the cloth for

Mourning White, and then to put it to the Dyers in gross, which is like to

save the Crown a good deal of money, the Drapers murmure extreamely at the

Lord Cranfield for it!

The colony of Scots in London

survived, but following the death of the King who brought about its

establishment, it faded into the intricate background of the metropolis, and

for the remainder of the century the majority of its members were anonymous

figures in a grim struggle for existence. It is pleasant to record, however,

that while poverty and destitution overtook many of them, the helping hand

was always extended to them by die more fortunate members of the community.

The charity was symbolized by the Scots Poor Box, which had been established

in 1613 by a group of Scottish journeymen who pledged themselves to help

each other, and so avoid becoming a burden upon strangers. The entrance fee

to this curious friendly society was five shillings, and each member

contributed sixpence per quarter to the common fund. The money thus

accumulated was lent out on bond, without interest, to needy members of the

fraternal group ; a considerable portion of it was used to meet the expenses

of sickness and burial. On October 5th, 1658, the money in the box was

counted—in the presence of the members—and found to amount to £61 3s. 6d.

The society, in 1665, was

granted a Charter of Incorporation under the title of The Scottish

Corporation, and was empowered to hold lands and to erect a hospital for the

reception of the objects of its charity. That very year the Great Plague

swept through London, and more than three hundred Scottish people were

buried in London at the expense of the Scots Poor Box.

Better days were at the

dawning, however. The membership of the society increased steadily—a sure

sign that Scots were invading London in increasing numbers—and the canny

officers deemed it prudent to declare that

wee doe require and command

the Masters, Governors, and Assistants of the said Hospital [The Royal

Scottish Hospital, built by the society in Bridge Street, Blackfriars, a few

years after it secured its first charter.] and their successors, that they

doe from tyme to tyme take special care not to encourage or receive any

vagrant beggars or other idle and dissolute persons of the Scottish Nacion

who are able to worke, and who are not fitte to receive the charity erected

and established by these our Letters Patent.

Greedy and thankless hands

were dipping into the Scots Poor Box, but its hard-headed custodians soon

changed that, and the fund continued to grow. Scots of wealth and influence

were beginning to join the Society, for Dr. Gilbert Burnet, [Bishop Burnet

had a remarkable career. He took his M.A. at Edinburgh at the age of

fourteen, and soon after entered Holy Orders. As a result of his forceful

and independent utterances on religious questions, he was obliged to leave

Scotland. In England he wrote a history of the Reformation. His

denunciations of the Catholics resulted in his being accused of treason, and

he fled to Holland. To avoid arrest there he became a Dutch citizen, but

fate brought him back to England, as the friend and adviser of King

William.] the famous Bishop, appears as a patron of the organization in

1682, to the tune of a pound, half-yearly. Substantial gifts swelled the

fund, and it grew steadily as the years passed, till, in our time, it

assumed the status of an opulent and carefully managed trust. The original

Scots Poor Box still exists, and it comes down to us as a striking symbol of

the independence and kindliness of the first Scots who settled in England.

In the realm of politics, the

death of King James marked the beginning of a long period of confusions and

alarms, and as we glance back we see the country being hammered out on the

anvil of internal struggle and strife. Charles sits on the throne and, like

his father, has pushed the Royal Prerogative to the utmost, doing without a

parliament between 1629 and 1640 and tyrannizing the people. Laud has forced

his prayer-book upon the Scottish people, and Jenny Geddes has thrown her

stool at the head of the Edinburgh minister who had the temerity to "say

mass at her lug" ! It is war again. The Covenanters, under Alexander Leslie,

have scattered the English levies at Newburn ; the proud Charles has begged

for a truce, and as a result of that war of the Bishops the Scots have

established, for England, the authority of parliament in these islands.

The Short and Long

Parliaments have come and gone; the shadow of Cromwell has fallen across

England; Charles Stuart, "that man of blood", has been executed; and the

Commonwealth is under the heel of a ruthless military dictator. The Scottish

Army has been scattered at Worcester; Charles II

has scurried to France; the Scots Parliament has been abolished; and

Cromwell has bawled the Rump Parliament out of the House of Commons. A

dictator straddles England, and the mailed fist bears so heavily upon the

people that they have discovered that the Stuarts were not dictators at all.

Cromwell has gone to his reward, Charles II has

come back to the throne, the Great Plague and the Great Fire have swept

London, the Dutch fleet has sailed up the Thames, the "Popish Plot" has

thrown England into one of its recurrent panics, the King himself has

checkmated the slavering Whigs, and with that act of common sense and

toleration to his credit has passed for ever from the stage.

The pregnant years slip past.

King James II has come to the throne, determined,

like his grandfather, to put parliament in its place. Monmouth has been

disposed of; Judge Jeffreys has completed his reign of judicial terror; the

attempt of the royal zealot to foist Catholicism on the country has failed;

the nobles, alarmed by the birth of James's son, have invited William of

Orange to come over the sea; James, frustrated, has left hurriedly for

France; and William and Mary, after making a declaration that was drawn up

for them by a Gilbert Burnet, have been acclaimed King and Queen of England

and Scotland.

The harsh drama continues

down the years. In Scotland, the persecutor of the Covenanters, Viscount

Dundee, has been shot at Killiecrankie, and the Highland Army he raised for

King James has been scattered. "That set of thieves", the Macdonalds of

Glencoe, has been extirpated by the Campbell butchers; William has beaten

James at the battle of the Boyne, and one of the first reasonable Kings that

the country has ever seen sits securely on the throne, smiling tolerantly at

the efforts of parliament to re-establish its long-lost dignity and

authority.

The turbulent century is

drawing rapidly to a close, but before it runs its course several notable

Scotsmen have made important contributions to the intellectual life of

England. John Napier of Merchiston [Napier, whose invention of logarithms

was published in 1614, maybe safely described as the greatest mathematical

genius that this country has produced.] has published his Logarithmorum

Canonis Descriptio. Sir Robert Murray, sometimes called Moray, [The Royal

Society met for the first time on 28th November, 1660, and its establishment

was the result of the efforts of Sir Robert Murray, who became its first

President on 6th March, 1661.] has founded the Royal Society, and has been

elected its first President. Gilbert Burnet, who came over the sea with

William and Mary, has been consecrated to the See of Salisbury by a

commission of English Bishops; has established the School of Divinity at

Salisbury; and has proven himself to be a worthy forerunner of the

succession of Scottish ecclesiastical statesmen who were destined to assume

the leadership of that august spiritual army, the Church of England. [The

record of Scotsmen in the Church of England is indeed a proud one. Until the

year 1864 no priest in Scottish Orders was permitted to hold a living in the

Church of England—a disability imposed upon the Scottish clergy as a result

of their Jacobite leanings in the preceding century. Four years after the

restriction was removed, a Scotsman occupied the Archiepiscopal See of

Canterbury. This was Archibald Campbell Tait, who was born in Edinburgh on

21st December, 1811. He was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1868 to 1882. In

1903 another Scotsman, the late Randall Thomas Davidson, born at Muirhouse,

near Edinburgh, on 7th April, 1848, became Archbishop, and this great

ecclesiastical statesman occupied the See for twenty-five years. The present

Archbishop of Canterbury, Cosmo Gordon Lang, who succeeded the late

Archbishop Davidson, was born at Fyvie, in Aberdeenshire, on 31st October,

1864—in the year that saw the removal of the English Church restrictions

against priests in Scottish Orders. In the seventy intervening years,

therefore, three Scotsmen have occupied the Archiepiscopal See of Canterbury

during forty-five years.]

James Gregory, born at

Drumoak, Aberdeenshire, in 1638, has turned up in London at the age of

twenty-four, with an intricate scientific paper in his pocket—and little

else. Fortunately, friendly Scotsmen dominated the council of the Royal

Society, and the young Aberdonian succeeded in getting his queer paper

printed. It was a description of the reflecting telescope, which he

invented.

David Gregory, another

Aberdonian, has become Professor of Astronomy at Oxford University, on the

recommendation of Sir Isaac Newton.

James Gibb, another

Aberdonian, has gone to London to seek an outlet for his architectural

genius, and has designed the famous Radcliffe Library at Oxford.

John Arbuthnot, the son of a

Kincardineshire minister, has taken his medical degree at Aberdeen, and the

closing years of the century find this urbane and talented man teaching

mathematics and administering physic in London in order to earn his bread.

These poor Scottish physicians in London, however, seemed to have the habit

of attending important horse-races. It may have been in the capacity of

horse-doctors. At any rate, the good Doctor Arbuthnot was at Epsom one day.

Prince George of Denmark was there also, and apparently he had backed the

wrong horses or mixed his drinks badly, for he suddenly became ill. There

was a hurried search for physicians, but as most of them were probably

arguing with bookmakers, Arbuthnot was the only one forthcoming. He felt the

royal pulse, calmed the royal mind, and went home with his patient. No more

teaching mathematics to morons for John Arbuthnot ! He became the favourite

physician of Queen Anne, and in his spare time collected coins and wrote

philosophical brochures and humorous squibs that contained a core of shrewd

and kindly philosophy. It was one of these latter, entitled The History of

John Bull, that sent his name sounding down the corridors of British

history, for it conferred upon the Englishman his familiar sobriquet.

In the realm of commerce it

fell to the lot of a Scot to lay the foundations of the most austere and

powerful financial institution ever established in the British Empire—the

Bank of England—but the story of William Paterson, of Dumfriesshire, takes

us far into the eighteenth century, and will be told later.

We look forward into the new

century, so fateful for Scotland—and England. The year is 1706. A great

event dominates everything. The complete union of the two countries is about

to be consummated. The accelerating drift towards the fusion of the two

parliaments is caused by mutual fears and suspicions. England, still in the

coils of religious fanaticism, is haunted by the dreadful thought that the

Stuarts still coveted the throne. Scotland, still dominated by her corrupt

nobility, [It is not too much to say that the odious record of Scottish

noblemen in pre-Union days is responsible, to a large extent, for the

strange paralysis of Scotland's political genius to-day. The lively

advocates of Home Rule are beginning to find this out.] and suspicious of

everything English, is afraid that she will be overrun by the ancient enemy.

That fear, in the light of subsequent developments, turned out to be one of

the greatest jokes of history!

We need not do more than

mention, in passing, the gross bribery and corruption that were a feature of

the negotiations leading to union. English bribery and coercion were

equalled by the shabby veniality of the Scottish gentry who shared in "The

Equivalent", a paltry sum of £398,000, of which some bonnet lairds were mean

enough to accept, as their payment for furthering the coup d'etat, sums less

than twelve pounds.

The unholy alliance was

consummated, in darkness and fear, the commissioners moving at their task

like furtive figures in a conspiracy. They proceeded, doubtless, in the

comforting philosophy that the end justified the means. When at last the

time came for the Scottish commissioners to affix their signatures to the

Treaty, they were in a state bordering on nervous collapse, so fearful were

they of the state of public opinion. The Treaty may be seen in Edinburgh

to-day, and the shaky signatures it bears are curious reminders of the

craven feelings of the so-called statesmen who cowered behind the document.

The final proceedings were carried out in secrecy, the commissioners

affixing their palsied signatures to the parchment in the summer-house of

the garden of the Earl of Seafield. Even in this sequestered spot, the

menacing growl of the Scottish mob reached their ears, and in a fresh access

of terror they scurried to safer rendezvous, the remaining names being added

to the Treaty in a cellar opposite the Tron Church, in High Street. Jacta

aha est! It had cost England money to accomplish what her soldiers had never

been able to accomplish, but it was probably the greatest political

achievement of her entire history, for, as will be seen in the pages that

follow, it brought her power and wealth beyond her wildest dreams.

From the period of the Roman

occupations to the dawn of the eighteenth century, Scotland's history was an

almost unbroken record of internal strife and scheming in high places,

savage religious conflicts which repressed the people and endowed them with

the dourness which is still one of their most noticeable characteristics,

and fruitless wars with England. Few countries have come through so many

centuries of turmoil and misery. Certainly no country on the face of the

earth ever fought so stubbornly and at such great cost to maintain its

independence. Adversity makes men, however, and out of the long years of

struggle and bloodshed a glorious fact emerged—the fact that the common

people never failed to rise up in defence of the honour of their country.

Adversity, long sustained, had not crushed them. On the contrary, it had

hardened them. Fired in the crucible of a thousand years of war, the

peasants and artisans of the country had preserved, untarnished, that inner

integrity of the soul that is the hall mark of a dominant and unconquerable

breed.

The common people. We are to

hear more about them, and less about the inept and corrupt nobility, in the

new century. The true genius of the country is about to flower in full

profusion at last. A new Scotland emerges from the reeking debris of the

centuries—not the Scotland of vicious assassinations and religious bigotry,

but the Scotland of industry, learning, and strict but healthy piety.

The blooms of the new genius

came out of the soil, in a thousand places. From remote cottages, where

poverty dwelt, came distinguished scholars, [A striking illustration of the

mysterious way in which genius bloomed in Scotland at this period is

afforded by the career of Alexander Murray, D.D., the great linguist. He was

born on 22nd October, 1775, at Dunkitterick, in the loneliest wilds of

Galloway, where his father was a shepherd. A delicate child, he was unequal

to the long walk to the nearest school, and his father taught him the

alphabet at home, drawing the letters on the floor of the cottage with a

burnt stick. At the age of seventeen the boy had had only thirteen months of

schooling, but he had made himself proficient in English, and had, in

addition, mastered Latin, Greek, Hebrew, French, and German. With the help

of Robert Burns, the poet, and the parish minister of Minnigaff, he was sent

to Edinburgh University, where he astounded the examiners by his knowledge

of languages. He had a command of every European language, including the

Lappish tongue. In 1811 he translated an Ethiopic letter for George III, and

at that time he was the only man in Great Britain capable of translating it.

This self-taught shepherd's son eventually became Professor of Oriental

Languages at Edinburgh University.] physicians, inventors, engineers,

financiers, and statesmen—the richest and most varied crop of practical

genius that ever sprang from the soil of this or any other country. It was

as if Scotland was making a superhuman effort to counterbalance the dismal

succession of tragedies that had brought her to darkness and despair in the

preceding centuries. A terrific virility pounded in the veins of the people.

Little Scotland could not harness it. It flowed across the border like a

molten stream, changing England, changing the Empire, changing the world.

Nothing like it has ever been witnessed since the dawn of history. Rome was

a mighty growth of opulent centuries when she straddled the world with the

naked sword. Scotland, when she unleashed her power, was the poorest country

in Europe, with only a million inhabitants. Yet by the sheer compression of

her awakened genius, and the terrific impact of her composite character, she

laid the foundations and raised the proud structure of modern England. As we

move into the new century we shall see the proofs of that statement

accumulating thick and fast.