1611, Nov 4

The Privy Council was at this time obliged to renew former acts against

Night-walkers of the city of Edinburgh—namely, idle and debauched

persons who went about the streets during the night, in the indulgence of

wild humours, and sometimes committing heinous crimes. If it be borne in

mind that there was at that time no system of lighting for the streets of

the city, but that after twilight all was sunk in Cimmerian darkness,

saving for the occasional light of the moon and stars, the reader will be

the better able to appreciate the state of things revealed by this public

act.

Reference is made to ‘sundry idle and deboshit persons,

partly strangers, who, debording in all kind of excess, riot, and

drunkenness. . . . commit sundry enormities upon

his majesty’s peaceable and guid subjects, not sparing the ordinar

officers of the burgh, who are appointit to watch the streets of the

same—of whom lately some has been cruelly and unmercifully slain, and

others left for deid.’ The Council ordered that no persons of any estate

whatsoever presume hereafter to remain on the streets ‘after the ringing

of the ten-hour bell at night.’ The magistrates were also ordained to

appoint some persons to guard the streets, and apprehend all whom they

might find there after the hour stated.—P. C. R.

1612

In this year there happened a strife between the Earl of Caithness on the

one side, and Sir Robert Gordon of Gordonston and Donald Mackay on the

other, highly illustrative of a state of things when law had only asserted

a partial predominancy over barbarism.

One Arthur Smith, a native of Banff, had been in

trouble for coining so long ago as 1599, when his man actually suffered

death for that crime. He himself contrived to escape justice, by making a

lock of peculiarly fine device, by which he gained favour with the king.

Entering into the service of the Earl of Caithness, he lived for seven or

eight years, working diligently, in a recess called the Gote, under Castle

Sinclair, on the rocky coast of that northern district. If we are to

believe Sir Robert Gordon, the enemy of the Earl of Caithness, there was a

secret passage from his lordship’s bedroom into the Gote, where Smith was

often heard working by night, and at last Caithness, Sutherland, and

Orkney were found full of false coin, both silver and gold. On Sir

Robert’s representation of the case, a commission was given to him by the

Privy Council to apprehend Smith and bring him to Edinburgh.

While the execution of this was pending, one William

MacAngus MacRorie, a noted freebooter, was committed to Castle Sinclair,

and there bound in fetters. Contriving to shift off his irons, William got

to the walls of the castle, and jumping from them down into the sea which

dashes on the rocks at a great depth below, swam safely ashore, and

escaped into Strathnaver. There an attempt was made by the Sinclairs to

seize him; but he eluded them, and they only could lay hold of one Angus

Herriach, whom they believed to have assisted the culprit in making his

escape. This man being taken to Castle Sinclair without warrant, and there

confined, Mackay was brought into the field to rescue his man—for so Angus

was—and Caithness was forced to give him up.

May

The coiner Smith was living quietly in the town of Thurso,

it under the protection of the Earl of

Caithness, when a party of Gordons and Mackays came to execute the

commission for apprehending him. They had seized the fellow, with a

quantity of false money he had about him, and were making off, when a set

of Sinclairs, headed by the earl’s nephew, John Sinclair of Stirkoke, came

to the rescue with a backing of town’s-people, and a deadly conflict took

place in the streets. Stirkoke was slain, his brother severely wounded,

and the rescuing party beat back. During the tumult, Smith was coolly put

to death, lest he should by any chance escape. The invading party were

then allowed to retire without further molestation. ‘The Earl of Caithness

was exceedingly grieved for the slaughter of his nephew, and was much

more vexed that such a disgraceful contempt, as he thought, should

have been offered to him in the heart of his own country, and in his chief

town; the like whereof had not been enterprised against him or his

predecessors.’

The strife is now transferred in partially legal form

to Edinburgh, where the parties had counter-actions against each other

before the Privy Council. Why the word partially is here used, will

appear from Sir Robert Gordon’s account of the procedure. ‘Both parties

did come to Edinburgh at the appointed day, where they did assemble all

their friends. There were with the Earl of Caithness and his son

Berriedale, the Lord Gray, the Laird of Roslin, the Laird of Cowdenknowes

(the earl’s sister’s son), the Lairds of Murkle and Greenland (the earl's

two brethren); these were the chief men of their company. There were with

Sir Robert Gordon and Donald Mackay, the Earl of Winton and his brother

the Earl of Eglintoun, with all their followers; the Earl of Linlithgow,

with the Livingstones; the Lord Elphinstone, with his friends; the Lord

Forbes, with his friends; Sir John Stewart, captain of Dumbarton (the Duke

of Lennox’s bastard son); the Lord Balfour; the Laird of Lairg Mackay in

Galloway; the Laird of Foulis, with the Monroes; the Laird of Duffus;

divers of the surname of Gordon . . . . with

sundry other gentlemen of name too long to set down. The Earl of Caithness

was much grieved that neither the Earl of Sutherland in person, nor

Hutcheon Mackay, were present. It galled him to the heart to be thus

overmatched, as he said, by seconds and children; for so it pleased him to

call his adversaries. Thus, both parties went weel accompanied to the

council-house from their lodgings; but few were suffered to go in when the

parties were called before the Council.’

All of these friends had, of course, come to see

justice done to their respective principals—that is, to outbrave each

other in forcing a favourable decision as far as possible. What followed

is equally characteristic. While the Council was endeavouring to exact

security from the several parties for their keeping the peace, both sent

off private friends to the king to give him a favourable impression of

their cases. ‘The king, in his wisdom, considering how much this

controversy might hinder and endamage the peace and quietness of his realm

in the parts where they did live, happening between persons powerful in

their own countries, and strong in parties and alliances, did write thrice

very effectually to the Privy Council, to take up this matter from the

rigour of law and justice unto the decision and mediation of friends.’

The Council acted accordingly, but not without great difficulty. While the

matter was pending, Lord Gordon, son of the Marquis of Huntly, happened to

come to Edinburgh from court; and his friends, having access to him, were

believed by the Earl of Caithness to have given him a favourable view of

their case against himself ‘So, late in the evening, the Lord Gordon

coming from his own lodging, accompanied with Sir Alexander Gordon and

sundry others of the Sutherland men, met the Earl of Caithness and his

company upon the High Street, between the Cross and the Tron. At the first

sight, they fell to jostling and talking; then to drawing of swords.

Friends assembled speedily on all hands. Sir Robert Gordon and Mackay,

with the rest of the company, came presently to them; but the Earl of

Caithness, after some blows, given and received, perceiving that he could

not make his part good, left the street, and retired to his lodging; and

if the darkness of the night had not favoured him, he had not escaped so.

The Lord Gordon, taking this broil very highly, was not satisfied that the

Earl of Caithness had given him place, and departed; but, moreover, he,

with all his company, crossed thrice the Earl of Caithness his lodging,

thereby to provoke him to come forth; but perceiving no appearance

thereof, he retired himself to his own lodging. The next day, the Earl of

Caithness and the Lord Gordon were called before the Lords of the Privy

Council, and reconciled in their presence.’

It was not till several years later that these troubles

came to an end.

Mar 28

Proceeding upon the principle that the smallest trait of industrial

enterprise forms an interesting variety on the too ample details of

barbarism here calling to be recorded, I remark with pleasure a letter of

the king of this date, agreeing to the proposal lately brought before him

by a Fleming—namely, to set up a work for the making of ‘brinston,

vitreall, and allome,’ in Scotland, on condition that he received a

privilege excluding rivalry for the space of thirteen years. About the

same time, one Archibald Campbell obtained a privilege to induce him ‘to

bring in strangers to make red herrings.’ In June 1613, he petitioned that

the king would grant him, by way of pension for his further encouragement,

the fourteen lasts of herrings yearly paid to his majesty by the Earl of

Argyle, ‘as the duty of the tack of the assize of herrings of those parts

set to him,’ being of the value of £38 yearly.—M. S. P.

Mar 29

Some of the principal Border gentlemen—Scott of Harden, Scott of Tushielaw,

Scott of Stirkfield, Gladstones of Cocklaw, Elliot of Falnash, and

others—had a meeting at Jedburgh, with a view to making a final and

decisive effort for stopping that system of blood and robbery by which the

land had been so long harassed, even to the causing of several valuable

lands to be left altogether desolate. They entered into a sort of bond,

declaring their abhorrence of all the ordinary violences, and agreeing

thenceforth to shew no countenance to any lawless persons, but to stand

firm with the government in putting them down. Even where the culprits

were their own dependents or tenants, they were to take part in bringing

them to justice, and, if they fled, were to deprive them of their ‘tacks

and steedings,’ and ‘put in other persons to occupy the same.’ Should any

fail to act in this way, or to pursue culprits to justice, they agreed

that a share of guilt should lie with that person. This bond seems to have

been executed with the concurrence of the state-officers, and more

especially under encouragement from the king, who, they say, had shewn his

anxiety every way ‘for the suppressing of that infamous byke of lawless

limmers.’

Mar / Apr

The Presbyterian historian of this period notes, that ‘in the months of

March and April fell forth prodigious works and rare accidents. A cow

brought forth fourteen great dog-whelps, instead of calves. Another, after

the calving, became stark mad, so that the owner was forced to slay her. A

dead bairn was found in her belly. A third brought forth a calf with two

heads. One of the Earl of Argyle’s servants being sick, vomited two toads

and a serpent, and so convalesced; but after[wards] vomited a number of

little toads. A man beside Glasgow murdered both his father and mother. A

young man going at the plough near Kirkliston, killeth his own son

accidentally with the throwing of a stone, goeth home and hangeth himself.

His wife, lately delivered of a child, running out of the house to seek

her husband, a sow had eaten her child.’—Cal. It is curious thus to

see what a former age was capable of believing. The circumstances here

related regarding the first two cows are now known to be impossibilities;

and no such relation, accordingly, could move one step beyond the mouths

of the vulgar with whom it originated. Yet it found a place in the work of

a learned church historian of the seventeenth century.

June

There was at this time an ‘extraordinary drowth, whilk is likely to burn

up and destroy the corns and fruits of the ground.’ On this account, a

fast was ordered at Aberdeen.—A. K. S. R. In September, and

for some months after, there are notices of ‘great dearth of victual,’

doubtless the consequence of this drouth. ‘The victual at ten pound the

boll.’—Chron. Perth.

July 28

Gregor Beg Macgregor, and nine others of his unhappy clan, were tried for

sundry acts of robbery, oppression, and murder; and being all found

guilty, were sentenced to be hanged on the Burgh-moor of Edinburgh.—Pit.

The relics of the broken Clan Gregor lived at this time a wild

predaceous life on the borders of the lowlands of Perthshire—a fearful

problem to the authorities of the country, from the king downward. One

called Robin Abroch, from the nativity of his father (Lochaber), stood

prominently out as a clever chief of banditti, being reported, says Sir

Thomas Hamilton, king’s advocate, as ‘the most bluidy murderer and

oppressor of all that damned race, and most terrible to all the honest men

of the country.' In a memoir of the contemporary Earl of Perth occurs an

anecdote of Robin, which, though somewhat obscure, speaks precisely of the

style of events which modern times have seen in the Abruzzi and the

fastnesses of the Apennines. The incident seems to have occurred in 1611.

‘In the meantime, some dozen of the Clan Gregor came

within the laigh of the country—Robin Abroch, Patrick M’Inchater,

and Gregor Gair, being chiefs. This Abroch sent to my chamberlain, David

Drummond, desiring to speak to him. After conference, Robin Abroch, for

reasons known to himself:, alleging his comrades and followers were to

betray him, was contented to take the advantage, and let them fall into

the hands of justice. The plot was cunningly contrived, and six of that

number were killed on the ground where, with certain friends, was present;

three were taken, and one escaped, by Robin and his man. This execution

raised great speeches in the country, and made many acknowledge that these

troubles were put to ane end, wherewith King James himself was well

pleased for the time.’ We nevertheless find the king’s advocate soon after

desiring of the king that, for the sake of public peace, he would withdraw

a certain measure of protection he had extended to Robin, and replace him

under the same restrictions as had been prescribed to the rest of his

clan.

In this year, a large body of troops was levied in

Scotland in a clandestine manner for the service of the king of Sweden, in

his unsuccessful war with Christian IV. of Denmark. As the king of Great

Britain was brother-in-law of the latter monarch, this illegal levying of

troops was an act of the greater presumption. The Privy Council fulminated

edicts against the proceedings as most obnoxious to the king, but without

effect. One George Sinclair—a natural brother of the Earl of Caithness,

and who, if we are to believe Sir Robert Gordon (an enemy), had stained

himself by a participation in the treacherous rendition of Lord

Maxwell—sailed with nine hundred men, whom he had raised in the extreme

north.

The successful course of the king of Denmark’s arms had

at this time closed up the ordinary and most ready access to Sweden at

Gottenburg, and along the adjacent coast. A Colonel Munckhaven, in

bringing a large levy of mercenaries from the Netherlands in the spring of

1612, had consequently been obliged to take the riskful step of passing

through Norway, then a portion of the dominions of the Danish monarch. The

greater part of his soldiery entered the Trondiem Fiord, landed at

Stordalen, and proceeded through the mountainous regions of Jempteland

towards Stockholm, where they arrived in time to save it from the threats

of the Danish fleet.

Colonel Sinclair resolved to take a similar course; but

he was less fortunate. Landing in Romsdalen, he was proceeding across

Gulbrandsdalen, and had entered a narrow pass at Kringelen, utterly

unsuspicious of the presence of an enemy, when he fell into a dire

ambuscade formed by the peasantry. Even when aware that a hostile party

had assembled, he was craftily beguiled on by the appearance of a handful

of rustic marksmen on the opposite side of the river, whose irregular

firing he despised, till his column had arrived at the most difficult part

of the pass. The boors then appeared amongst the rocks above him, in front

and in rear, closing up every channel of egress. Sinclair fell early in

the conflict. The most of his party were either cut off by the marksmen,

or dashed to pieces by huge rocks tumbled down from above. Of the nine

hundred, but sixty were spared. These were taken as prisoners to the

houses of various boors, who, however, soon tired of keeping them. It is

stated that the wretched Scots were brought together one day in a large

meadow, and there murdered in cold blood. Only one escaped.

The Norwegians celebrated this affair in a vaunting

ballad, and, strange to say, still look back upon the destruction of

Sinclair’s party as a glorious achievement. In the pass of Kringelen,

there is a tablet bearing an inscription to the following purport: ‘Here

lies Colonel Sinclair, who, with nine hundred Scotsmen, was dashed to

pieces like clay-pots by three hundred boon of Lessöe, Vaage, and Froen.

Berdon Segelstadt of Ringeböe was the

leader of the boors.’ In a peasant’s house near by were shewn to me, in

1849, a few relies of the poor Caithness-men—a matchlock or two, a

broadsword, a couple of powder-flasks, and the wooden part of a drum.

1613

After the treacherous slaughter of the Laird of Johnston in 1608, Lord

Maxwell was so hotly prosecuted by the state-officers, as to be compelled

to leave his country. His Good-night, a pathetic ballad, in which

he takes leave of his lady and friends, is printed in the Border

Minstrelsy: afterwards, he returned to Scotland, but could not shew

himself in public. A succession of skulking adventures ended in his being

treacherously given up to justice by his relative, the Earl of Caithness;

and he was, without loss of time, beheaded at the Cross of Edinburgh—the

sole noble victim to justice out of many of his order who, during the

preceding thirty years, had deserved such a fate.

When informed by the magistrates of the city that they

had got orders for his execution, he professed submission to the will of

God and the king, but declined the attendance of any ministers, as he

adhered to the ancient religion. ‘It being foreseen by the bailies and

others that gif he sould at his death enter in any discourse of that

subject before the people, it might breed offence and selander, he was

desirit, and yielded to bind himself by promise, to forbear at his death

all mention of his particular opinion of religion, except the profession

of Christianity; which he sinsyne repented, as he declared to the bailies,

when they were bringing him to the scaffold.’ On the scaffold, the

unfortunate noble expressed his hope that the king would restore the

family inheritance to his brother. He likewise ‘asked forgiveness of the

Laird of Johnston, his mother, grandmother, and friends, acknowledging the

wrong and harm done to them, with protestation that it was without

dishonour for the worldly part of it. Then he retired himself near the

block, and made his prayers to God; which being ended, he took leave of

his friends and of the bailies of the town, and, suffering his eyes to be

covered with ane handkerchief, offered his head to the axe.’

Thus at length ended the feud between the Johnstons and

Maxwells, after, as has been remarked, causing the deaths of two chiefs of

each house.

Aug

Edward Lord Bruce of Kinloss lost his life in a duel fought near

Bergen-op-zoom with Sir Edward Sackville, afterwards Earl of Dorset. They

were gay young men, living a life of pleasure in London, and in good

friendship with each other, when some occurrence, arising out of their

pleasures, divided them in an irremediable quarrel. Clarendon states that

on Sackville’s part the cause was ‘unwarrantable.’ Lord Kinloss, in his

challenge, reveals to us that they had shaken hands after the first

offence, but with this remarkable expression on his own part, that he

reserved the heart for a truer reconciliation. Afterwards, in France,

Kinloss learned that Sackville spoke injuriously of him, and immediately

wrote to propose a hostile meeting. ‘Be master,’ he said, ‘of your own

weapons and time; the place wheresoever I will wait on you. By doing this,

you will shorten revenge, and clear the idle opinion the world hath of

both our worths.’

Sackville received this letter at his father-in-law’s

house, in Derbyshire, and he lost no time in establishing himself, with

his friend, Sir John Heidon, at Tergoso, in Zealand, where he wrote to

Lord Kinloss, that he would wait for his arrival. The other immediately

proceeded thither, accompanied by an English gentleman named Crawford, who

was to act as his second; also by a surgeon and a servant. They met,

accompanied by their respective friends, at a spot near Bergen-op-Zoom,

‘where but a village divides the States’ territories from the archduke’s....

to the end that, having ended, he that could, might presently

exempt himself from the justice of the country by retiring into the

dominion not offended.’

In the preliminary arrangements, some humane articles

were agreed upon, probably by the influence of the seconds; but, if we are

to believe Sir Edward Sackville, Lord Kinloss, in choosing his adversary’s

weapon, expressed some blood-thirsty sentiments, that gave him reason to

hope for little mercy if he should be the vanquished party. Being on his

part incensed by these unworthy expressions, he, though heavy with a

recent dinner, hurried on the combat. To follow his remarkable narrative:

‘I being verily mad with anger [that] the Lord Bruce should thirst after

my life with a kind of assuredness, seeing I had come so far and

heedlessly to give him leave to regain his lost reputation, bade him

alight, which with all willingness he quickly granted; and there, in a

meadow ankle-deep in water at the least, bidding farewell to our doublets,

in our shirts began to charge each other; having afore commanded our

surgeons to withdraw themselves a pretty distance from us, conjuring them

besides, as they respected our favours or their own safeties, not to stir,

but suffer us to execute our pleasures; we being fully resolved (God

forgive us!) to despatch each other by what means we could. I made a

thrust at my enemy, but was short, and in drawing back my arm, I received

a great wound thereon, which I interpreted as a reward for my

short-shooting; but, in revenge, I pressed in to him, though I then missed

him also, and then received a wound in my right pap, which passed level

through my body, and almost to my back. And there we wrestled for the two

greatest and dearest prizes we could ever expect trial for—honour and

life; in which struggling, my hand, having but an ordinary glove on it,

lost one of her servants, though the meanest, which hung by a skin At

last, breathless, yet keeping our holds, there passed on both sides

propositions of quitting each other’s swords; but when amity was dead,

confidence could not live, and who should quit first, was the question;

which on neither part either would perform, and restriving again afresh,

with a kick and a wrench together, I freed my long captivated weapon;

which incontinently levying at his throat, being master still of his, I

demanded if he would ask his life, or yield his sword; both which, though

in that imminent danger, he bravely denied to do. Myself being wounded,

and feeling loss of blood, having three conduits running on me, which

began to make me faint, and he courageously persisting not to accord to

either of my propositions, through remembrance of his former bloody

desire, and feeling of my present state, I struck at his heart, but with

his avoiding missed my aim, yet passed through the body, and drawing out

my sword, repassed it again through another place, when he cried: "O, I am

slain!" seconding his speech with all the force he had to cast me; but

being too weak, after I had defended his assault, I easily became master

of him, laying him on his back, when, being upon him, I redemanded if he

would request his life; but it seemed he prized it not at so dear a rate

to be beholden for it, bravely replying, "he scorned it." Which answer of

his was so noble and worthy, as I protest I could not find in my heart to

offer him any more violence; only keeping him down, until at length his

surgeon, afar off, cried out, "he would immediately die if his wounds were

not stopped." Whereupon, I asked if he desired his surgeon should come,

which he accepted of; and so being drawn away, I never offered to take his

sword, accounting it inhuman to rob a dead man, for so I held him to be.

This thus ended, I retired to my surgeon, in whose arms, after I had

remained a while for want of blood, I lost my sight, and withal, as I then

thought, my life also. But strong water and his diligence quickly

recovered me, when I escaped a great danger. For my lord’s surgeon, when

nobody dreamt of it, came full at me with his lord’s sword; and had not

mine, with my sword, interposed himself, I had been slain by those base

hands; although my Lord Bruce, weltering in his blood, and past all

expectation of life, comformable to all his former carriage, which was

undoubtedly noble, cried out: "Rascal, hold thy hand!"

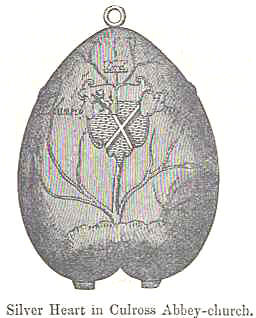

Thus miserably, a victim of passion, died a young

nobleman who might otherwise have lived a long and useful life. Being

childless, his title and estates went to his next brother, Thomas. Through

what means it came about, we cannot tell, but possibly it might be in

consequence of some recollection of a well-known circumstance in the

history of a former great man of his family, King Robert Bruce, the heirt

of Edward Lord Kinloss was enclosed in a silver case, brought to Scotland,

and deposited in the abbey-church of Culross, near the family seat. The

tale of the Silver Heart had faded into a family tradition of a

very obscure character, when, in 1808, this sad relic was discovered,

bearing on the exterior the name of the unfortunate duellist, and

containing what was believed to be the remains of a human heart. It was

again deposited in its original place, with an inscription calculated to

make the matter clear to posterity. The Bruce motto, FUIMUS, is also seen

on the wall, conveying to the visitor an indescribable feeling of

melancholy, as he reflects on the stormy passion which once swelled the

organ now resting within, and the wild details of that deadly quarrel of

days long gone by.

‘The unfortunate Lord Bruce saw distinctly the figure

or impression of a mort-head, on the looking-glass in his chamber, that

very morning he set out for the fatal place of rendezvous, where he lost

his life in a duel; and asked of some that stood by him if they observed

that strange appearance: which they answered in the negative. His remains

were interred at Bergen-op-Zoom, over which a monument was erected, with

the emblem of a looking-glass impressed with a mort-head, to perpetuate

the surprising representation which seemed to indicate his approaching

untimely end. I had this narration from a field-officer, whose honour and

candour is beyond suspicion, as he had it from General Stuart in the Dutch

service. The monument stood entire for a long time, until it was partly

defaced when that strong place was reduced by the weakness or treachery of

Cronstrom, the governor. ‘—Theophilus Insulanus's Treatise on the

Second-Sight 1763.

Sep 14

Robert Philip, a priest, returned from Rome in the summer of this year,

and performed mass in sundry places in a clandestine manner, but with the

proper dresses, utensils, and observances. One James Stewart, living at

the Nether Bow Port in Edinburgh, commonly called James of Jerusalem—a

noted papist and resetter of seminary priests—was accustomed to have

this condemned ceremonial performed in his house, in presence of a small

company. Both men were now tried for these offences; and two days after, a

third, John Logan, portioner of Restalrig, was also put to an assize, for

being one of the audience at Stewart’s house. One cannot, in these days of

tolerance, read without a strange sense of uncouthness, the solemn

expressions of horror employed in the dittays of the king’s advocate

against the offenders, being precisely the same expressions which were

used against heinous offences of a more tangible nature. Philip and

Stewart were condemned to banishment, and Logan, in as far as he expressed

penitence and shewed that he had since conformed to the kirk, and even

borne office in the session, was let off with a fine of one thousand

pounds!

Dec 1

Robert Erskine, brother of the lately deceased Laird of Dun, in

Forfarshire, was put upon trial for an offence that recalls the tale of

the Babes in the Wood. To open the succession to himself, be formed the

resolution to put away his two nephews, John and Alexander Erskine,

minors, and for this purpose consulted with his three sisters, Isobel,

Annas, and Helen. These women, readily entering into his views, attempted

to bribe a servant to engage a witch for the purpose of destroying the two

boys; but the man’s virtue was proof to the temptation. Annas and Helen

then made a journey across the Cairnamount to a place called the

Muir-alehouse, where dwelt a noted witch called Janet Irving. From her

they came back, bearing certain deadly herbs fitted for their purpose, and

gave these to their brother. He, doubtful of the efficacy of the herbs,

went himself to the witch, to get full assurance on that point; and,

finding reason to believe that they could destroy the two boys, lost no

time in making an infusion of them in ale, which he administered to his

victims in the house of their mother at Montrose. The effect was not

immediate; but it inflicted the most horrible torments upon the poor

youths, one of whom, after dwining for three years, died, uttering,

just before death, these affecting words: ‘Wo is me! that ever I had right

of succession to ony lands or living, for, gif I had been born some poor

cotter’s son, I had not been sae demeaned [treated], nor sic wicked

practices had been plotted against me for my lands!’ The other remained

without hope of recovery at the time of the trial.

Robert Erskine was found guilty and condemned to be

beheaded. His sisters were tried June 22, 1614, for their share of the

guilt, and also condemned to death, which two of them suffered. Helen

alone, as being less guilty and more penitent than the rest, had her

sentence commuted to banishment. The case must have been felt as deeply

afflicting by the friends of the Presbyterian cause, as these wretched

victims of the mean passion of avarice were the great-grandchildren of the

venerated reformer, John Erskine of Dun .—Pit.

1613

One John Stercovius, a Pole, had come into Scotland in the dress of his

country, which exciting much vulgar attention, he was hooted at on the

streets, and treated altogether so ill, that he was forced to make an

abrupt retreat. The poor man, returning full of wounded feelings to his

own country, published a Legend of Reproaches against the Scottish

nation—’ane infamous book against all estates of persons in this

kingdom.’—P. C. R. It will now be scarcely believed, in

Scotland or elsewhere, that King James, hearing of this libel, employed

Patrick Gordon, a foreign agent—himself a man of letters—to raise a

prosecution against Stercovius in his own country, and had the power to

cause the unhappy libeller to be beheaded for his offence! The affair cost

six thousand merks, and a convention of burghs was called (December 3,

1613), to consider means of raising this sum by taxation. This mode of

raising the money having failed, the king made an effort to obtain aid for

the payment of the money from the English resident in the town of Danzig—with

what result does not appear. It is a notable circumstance, that while

James was on the whole a mild administrator of justice, he was unrelenting

towards satirists, and the grossest judicial cruelties of his reign are

against men who had been in one way or another contumelious towards

himself.

1613, Dec 10

One of the king’s large ships-of-war, which had lain in the Roads of Leith

for six weeks, and was about to set sail on her return to England, met her

destruction ‘about the twelfth hour of the day,’ through the mad humour of

an Englishman, who, while the captain and some of his officers were on

shore, laid trains of powder throughout the vessel, notwithstanding that

his own son was on board, along with about sixty other men. ‘The ship and

her whole provision were burnt; only the bottom and some of the munition

were safe. Twenty-four of the men were burnt or perished in the sea; the

rest ‘were mutilated and lamed, notwithstanding of all the help that could

be made. The fire made the ordnance to shoot, so that none durst come near

to help.’—Cal.

‘The sixty-three men that escaped were shipped and

transported to London.’—Bal.

Dec 16

The Privy Council of Scotland had this day under their consideration a

subject which must have sent their minds back to the associations of an

earlier and more romantic age. That custom among the people of the

Scottish Border, of going into Cheviot to hunt, which had led to the

dismal tragedy narrated in the well-known ballad of Chevy Chase,

was, it seems, still kept up. What was once the border of either country

being now the middle of both in their so far united condition, the king

felt the propriety of putting down a custom so apt to lead to bad blood

between his English and Scottish subjects; and accordingly, his council

now ordered that the inhabitants of Roxburgh and Selkirk shires, of

Liddesdale and Annandale, should cease their ancient practice of going

into Tynedale, Redesdale, the fells of Cheviot and Kidland, for hunting

and the cutting of wood, under pain of confiscation of their worldly

goods.—P. C. R.

1614, Jan 18

Hugh Weir of Cloburn, a boy of fourteen years, had been taken out of the

town of Edinburgh from his mother’s friends, and carried over to Ireland,

and there married to the daughter of the Laird of Corehouse. He ‘was, by

Sir James Hamilton’s means, apprehended in Ireland, and sent back to

Scotland, and presented to the Council. He was imprisoned in the Tolbooth,

in a room next the Laird of Blackwood, by whose means the boy was taken

away and sent into Ireland.’—Bal.

Mar 3

(Tuesday) at ‘half an hour to sax in the morning, ane earthquake had in

divers places.’ ‘On Thursday thereafter, ane other earthquake at 12 hours

in the night, had baith in land and burgh.’—Chron. Perth.

Aug 12

Theophilus Howard, Lord Walden (afterwards Earl of Suffolk), made a short

journey of pleasure in Scotland; and as the details give some idea of the

means there were in the country of entertaining a stranger of distinction,

they may be worth noting. His lordship was received by the Earl of Home

into Dunglass House, in Berwickshire, and ‘used very honourably.’ He dined

next day with his brother-in-law, Sir James Home of Cowdenknowes, at

Broxmouth House, near Thinbar. Advancing thence towards Edinburgh, he was

met by the secretary of state, Sir Thomas Hamilton of Binning, accompanied

by a number of gentlemen of the country, all of whom had waited for him

the preceding night at Musselburgh Links, but were disappointed of his

coming forward. He was by them convoyed to the Canongate, and lodged in

John Killoch’s house. Next morning, he proceeded to the Castle, and

‘viewed the site, fortification, and natural strength thereof.’ Having

dined, he rode from Edinburgh with the Lord Chancellor to Dunfermline,

where he was entertained with all kindness and respect till Monday, the

16th. He then went to Culross, to see Sir George Bruce’s coal-works, which

were one of the wonders of the age; ‘where, having received the best

entertainment they could make him, my Lord Chancellor took leave of him,

and left him to be convoyed by my Lord Erskine to Stirling, where he could

not be persuaded to stay above one night. The next day, he saw the park of

Stirling, dined in the Castle, and raid that night towards Falkland.’ On

the way, Lord Erskine transferred him to the care of Lord Scone, who,

assisted by many gentlemen of Fife, took him to his house in Falkland.’

There, doubtless to the great distress of Lord Scone, no entreaties could

prevail upon Lord Walden to stay longer than a night, ‘to receive that

entertainment which he wald gladly have made langer to him.’ So, ‘after

the sight of the park and palace, having dined, his lordship and my Lord

of Scone came to Burntisland, where he had ready and speedy passage; but

the wind being very loud, he was exceeding sick at sea.’ Landing at Leith,

the distinguished company was received for refreshment into the house of a

rich and prominent person of that day, Bernard Lindsay, whom we shall see

erelong entertaining Ben Jonson in the same place. Here the secretary

again took up the stranger, and convoyed him once more to John Killoch’s

in the Canongate, ‘whither the baillies of Edinburgh came to him, and

invited him to supper the next day, but could not induce him by any

entreaty to stay.’ Having dismissed them, he went to see the palace of

Holyrood. Next day, the 19th of August, he left Edinburgh, and rode with

the secretary to Seton, ‘where he was received by the Countess of Winton

and her children, and used with all due respect.’ After taking a sight of

the house, which was of princely elegance, with beautiful gardens, Lord

Walden proceeded to Broxmouth, and there spent the night.

‘In all his journey through this country,’ says the

contemporary writer, ‘great and loving respect has been borne to him by

all honest men, whereof he has proven most worthy; for he has esteemed all

things to the uttermost of their worth, and in his courteous discretion

has favourably excused all oversights and defects. Every honest man here

wishes him happiness in all his other journeys and enterprises, for the

honourable, wise, and humane behaviour he has used amang them.’

In this year, a small volume was printed and published

by Andro Hart of Edinburgh, under the title of Mirifici Logarithmorum

Canonis Descriptio, &e., Auctore et Inventore Joanne Napero, Barone

Merchistonii, Scoto. This was a remarkable event in the midst of so

many traits of barbarism, bigotry, and ignorance; for in Napier’s volume

was presented a mode of calculation forming an essential pre-requisite to

the solution of all the great problems involving numbers which have since

been brought before mankind. John Napier is believed to have been engaged

in the elaboration of his Logarithms for fully twenty years, while at the

same time giving some of his time to such inventions as burning-glasses

for the destruction of fleets, to theological discussions; and the occult

sciences. The tall, antique tower of Merchiston, in which he lived and

pursued his studies, still exists at the head of the Burgh-moor of

Edinburgh.

Napier’s little book was published in an English

translation by Henry Briggs of Oxford, the greatest mathematician of his

day in England. The admiration of Briggs for the person of Napier was

testified in the summer of 1615 by his paying a visit to Scotland, in

order to see him. Of this rencontre there is a curious and interesting

account preserved by William Lilly in his Life and Times. "I will

acquaint you,’ says he, ‘with one memorable story related unto me by John

Man, an excellent mathematician and geometrician, whom I conceive you

remember. He was a servant to King James I. and Charles I. When Merchiston

first published his Logarithms, Mr Briggs, then reader of the astronomy

lectures at Gresham College in London, was so surprised with admiration of

them, that he could have no quietness in himself until he had seen that

noble person whose only invention they were. He acquaints John Man

therewith, who went in [to] Scotland before Mr Briggs, purposely to be

there when these two so learned persons should meet. Mr Briggs appoints a

certain day when to meet at Edinburgh; but failing thereof, Merchiston was

fearful he would not come. It happened one day, as John Marr and Lord

Napier were speaking of Mr Briggs, "Oh! John," saith Merchiston, "Mr

Briggs will not came now." At the very instant, one knocks at the gate.

John Marr hasted down, and it proved to be Mr Briggs, to his great

contentment. He brings Mr Briggs into my lord’s chamber, where almost one

quarter of an hour was spent, each beholding other with admiration, before

one word was spoken. At last Mr Briggs began: "My lord, I have undertaken

this long journey purposely to see your person, and to know by what engine

of wit or ingenuity you came first to think of this most excellent help

unto astronomy—namely, the Logarithms; but, my lord, being by you found

out, I wonder nobody else found it out before, when, now being known, it

appears so easy." He was nobly entertained by the Lord Napier; and every

summer after that, during the laird’s being alive, this venerable man went

purposely to Scotland to visit him.’

As Napier (whom Lilly

erroneously calls lord) died in April 1617, Mr Briggs could not have made

more than one other summer pilgrimage to Merchiston.

Died John M’Birnie. minister of St Nicolas’ Church,

Aberdeen —a typical example of the more zealous and self-denying of the

Presbyterian clergy of that age. A similar one of the next age says of

M’Birnie: ‘I heard Lady Culross say: "He was a godly, zealous, and painful

preacher; and that he used always, when he rode, to have two Bibles

hanging at a leather girdle about his middle, the one original, the other

English; as also, a little sand-glass in a brazen ease: and being alone,

he read, or meditated, or prayed; and if any company were with him, he

would read or speak from the Word to them." . . . .

When he died, he called his wife, and told her he had no outward

means to leave her, or his only daughter, but that he had got good

assurance that the Lord would provide for them; and accordingly, the day

he was buried, the magistrates of the town came to the house, after the

burial, and brought two subscribed papers, one of a competent maintenance

to his wife during her life, another of a provision for his daughter.’

1615

The latter part of the winter 1614—15 was of such severity as to be

attended with several remarkable circumstances which were long remembered.

In February, the Tay was frozen over so strongly as to admit of passage

for both horse and man. ‘Upon Fasten’s E’en [February 21], there was twa

puncheons of Bourdeaux wine ‘carriet, sting and ling, on men’s

shoulders, on the ice, at the mids of the North Inch, the weight of the

puncheon and the bearers, estimate to three score twelve stane weight.’

This state of things, however, was inconvenient for the ferrymen, ‘being

thereby prejudgit of their commodity.’ So they, ‘in the night-time, brak

the ice at the entry, and stayit the passage.’—Chron. Perth.

An enormous fall of snow took place early in March, so

as to stop all comrnunication throughout the country. On its third day,

many men and horse perished in vain attempts to travel. The accumulation

of snow was beyond all that any man remembered. ‘In some places, men

devised snow-ploughs to clear the ground, and fodder the cattle.’ —Bat.

The snow fell to such a depth, and endured so long upon the ground,

that, according to Sir Robert Gordon, ‘most part of all the horse, nolt,

and sheep of the kingdom did perish, but chiefly in the north.’ [This

unheard-of snow-fall was equally notable in the south. When the thaw came,

it caused an unexampled flood in the Ouse of Yorkshire, which lasted ten

days, carrying away a great number of bridges. ‘After this storm followed

such fair and dry weather, that in April the ground was as dusty as in any

time of summer. The drought continued till the 20th

of August, and made such a scarcity of hay, beans, and barley, that

the former was sold at York for 30s. and 40s. a wainload.’—History

of York, 1785, i. 256.]

The Privy Council, viewing the ‘universal death,

destruction, and wrack of the beasts and goods throughout all parts of the

country,’ apprehended that, without some extraordinary care, there would

not be enough of lambs left to replenish the farms with sheep for future

use. They accordingly interfered with a decree forbidding the use of lamb

for a certain time. Nevertheless, so early as the 26th of April, it was

ascertained that there were undutiful subjects, who, ‘preferring their own

private contentment and their inordinate appetite, and the delicate

feeding of their bellies, to the reverence and obedience of the law,’

continued to use lamb, only purchasing it in secret places, as if no such

prohibition had ever been uttered. It was therefore become necessary that

severe punishment should be threatened for this offence. The threats

launched forth on this occasion were found next year to have been of some

effect in preserving the remnant of the lamb stock; and, to complete the

restoration of the stock, a new decree to the like effect was then made

(March 14, 1616).

Jan

The king and his English council having, with the usual short-sighted

policy of the age, decreed that no goods should be imported into or

exported out of England, except in English vessels, the burghs of Scotland

were not slow to perceive that the interests of their country would be

deeply injured thereby, as other states would of course establish similar

restrictions, ‘and if so, there is naething to be expected but decay and

wrack to our shipping, insaemickle as the best ships of Scotland are

continually employed in the service of Frenchmen, not only within the

dominions of France, but also within the bounds of Spain, Italy, and

Barbary, where their trade lies, whilk is ane chief cause of the increase

of the number of Scots ships and of their maintenance, whereas by the

contrary, the half of the number of ships whilk are presently in Scotland

will serve for our awn privat trade and negotiation.’

The king of France did in reality revenge the selfish

policy of England by issuing a similar order in favour of French shipping,

the first consequence of which was that an English vessel and a Dutch one,

lading in Normandy, were obliged to disburden themselves and come empty

home. ‘Ane Scottish bark perteining to Andrew Allan, whilk that same time

was lading with French merchandise,’ would have been subjected to the same

inconvenience, if the master had not pretended to an immunity in favour of

his country, through its ancient alliance with France, ‘inviolably kept

these 800 years bypast.’ The Scots factors in France entered a complaint

before the parliament of Paris, reminding it of that ancient alliance, and

pleading that the French had ever had liberty of trade in all Scottish

ports; shewing, indeed, that Scotland was not comprised in the edict of

the English monarch and his council. The parliament accordingly decreed

that the Scotch should remain in the enjoyment of freedom of trade within

France, as heretofore.

The attention of the king being necessarily called to

the interests of Scotland in this matter, he was found obstinate in favour

of the general principle of the English order in council. ‘Natural

reason,’ he said, ‘teaches us that Scotland, being part of an isle, cannot

be mainteined or preserved without shipping, and shipping cannot be

mainteined without employment; and the very law of nature teaeheth every

sort of corporation, kingdom, or country, first to set their own vessels

on work, before they employ any stranger.' He was willing, however, to

relax in particular cases. James argues logically, but he had not sagacity

to anticipate the doctrines of Adam Smith.