|

VERY soon after Morton had demitted

the regency, he partly recovered his power, and this he continued for some

time to exercise. The young king remained in Stirling Castle, under

considerable restraint. With a view to acquire some control over him, as

the only means of resisting the English or Protestant interest, his mother

and French grand-uncles sent to his court a young gentleman of engaging

manners, in whom they had confidence. This was Esme Stuart, usually called

Monsieur d’Aubigné, a member of the Lennox family, being nephew of the

late Regent, but who had been brought up in France. It was believed that

he carried with him forty thousand pieces of gold, to be employed in

winning favour with the Scottish nobility. ‘He was,’ says a contemporary,

‘a man of comely proportion, civil behaviour, red-beardit, honest in

conversation, weel likit of by the king and a part of his nobility at the

first" To aid him in his purpose, he brought with him one called Monsieur

Mombirneau, ‘a merry fellow, able in body and quick in spirit.' The young

king readily opened his heart to this pleasant relative, who took care to

accommodate himself to his tastes, and to assist, above all, in making his

time pass agreeably. About the same time, another but more distant

relative, James Stuart, of the Ochiltree family, a captain in the royal

guard, began to acquire favour with the king. This was altogether a less

worthy person than D’Aubigné, being arrogant, domineering, and vicious.

D’Aubigué, however, being a Catholic, and suspected of designs in favour

of popery, was perhaps the least liked of the two.

It was in September 1579, when

little more than thirteen years of age, that James was for the first time

so far liberated from the control of Morton and other councillors, as to

be able to leave his castle of Stirling. Accompanied by D’Aubigné, then

newly arrived, he made a formal visit to Edinburgh, where the citizens

gave him a most affectionate reception.

This was a more important crisis of

British history than is generally supposed. It was now that a commencement

was made of that struggle for authority which we see going on through the

remainder of this and the whole of the ensuing century. James had been

reared as the creature of the zealous Presbyterian party. When he began to

judge for himself, and to become conversant with minds beyond the range of

his earlier associations, his affections led him to prefer those who had

been his mother’s friends, and he soon came to believe that they and such

as they were likely to be his own warmest supporters. What was most

important of all, he found that the Presbyterian clergy, while professing

respect for him as the chief-magistrate of the land, and disposed to obey

him in civil matters, claimed to be, in things ecclesiastical, not merely

independent of him, but his superiors. Restricting the idea of the church

to those ‘exercising the spiritual function among the congregations of

them that profess the truth,’ they asserted that it had 'a certain power

granted by God,’ having ‘ground in the word of God,’ and ‘to be put into

execution by them unto whom the government of the kirk by lawful calling

is committed.’ And, ‘as the ministers and others of the ecclesiastical

state are subject to the magistrate civil, so aucht the person of the

magistrate to be subject to the kirk spiritually and in ecclesiastical

government.’ In their view, as far as his own religions and moral practice

was concerned, King James was only a parishioner of the Canongate. On the

other hand, when one of their order interfered with politics in his

sermon, he was only liable to be challenged by his presbytery. The claim

was presented by men of whose disinterestedness there can be no more doubt

than of their religious zeal; that it might have worked satisfactorily if

it had ever found a monarch who would cordially accept and submit to it,

cannot be denied, for we have had no experience on the subject, the final

settlement of the Scotch church at the Revolution having left it in a

doubtful state. The compromise which was attained at the end of a

century-long struggle, was unattainable in the days of King James. The

pretension only set him upon looking up scriptural texts too, texts which

could be interpreted as setting the royal authority equally above human

challenge; and such were not difficult to be found. Hence arose the

celebrated doctrine of the divine right of kings—a sort of antithesis to a

doctrine which would have made kings in one important respect the subjects

of a set of church-courts. And so commenced that unfortunate course of

things in our national history, which has presented this king as in

constant antagonism to the ecclesiastical forms and order of worship

preferred by the great bulk of his people, as seeking by all arts to

thrust hated systems upon them, and as founding a policy which, becoming a

deadly and obstinate struggle with his descendants, alternately gave us

anarchy and despotism, till it ended in the total overthrow of the main

line of the House of Stuart. Such were the natural fruits of the

earnestness, beautiful but terrible, with which men then seized and worked

out principles which they found, or thought they found, in the

Bible—arguing on the religion of peace and good-will to men, with swords

in their hands, and laws as cruel as swords, till a sense of the

inconsequentiality of such reasoning for any good at length came over most

of them with the sickening effect of a wind from a field of battle, and

disposed them to rest content with the sulky mutual protest in which they

have since lived.

Notwithstanding a strenuous

opposition from Elizabeth and the Presbyterian clergy, D’Aubigné, whom

James made Earl, and finally Duke of Lennox, succeeded in greatly

advancing the French interest. It was in vain that the ministers railed at

him as a papist: he coolly came before them and abjured popery. A

confession of faith, condemning the pope and all his pretensions and

works, was brought forward: James and his councillors, including the Earl

of Lennox, unhesitatingly signed it (January 28, 1580-1). Morton, who

alone possessed the personal character that could effectually stand for

the English interest and the kirk, had, by his cruel and avaricious

conduct, lost the support of all classes, the clergy included. It was even

found possible to effect the ruin of this great man. On the last of

December 1580, the adventurer Stuart came into the council-chamber, and,

falling on his knees, accused the ex-Regent of being concerned in the

murder of his majesty’s father. To the general surprise, he fell without a

struggle, and after a few months’ confinement, he perished on the scaffold

(June 2, 1581).

Under Lennox and Stuart—the latter

now created Earl of Arran—a movement was made for bringing an episcopate

into the church. Arran is said to have put the idea of absolute power into

the king’s mind, and a French alliance was threatened. The clergy, in

general assembly, showed their usual courage in protesting against the

court proceedings. The conduct of their moderator, Andrew Melville, was

specially remarkable. When he and his fellow-cornmissioners came before

the council with their grieves, Arran, according to a contemporary

narration, ‘begins to threaten, with thrawn brow and boasting lauguage.

"What!" says he, "wha dar subseryve thir treasonable articles?" Mr Andrew

answers: "We dar, and will subseryve them, and give our lives in the

cause!" And withal starts to, and taks the pen fra the clerk and

subseryves, and calls to the rest of his brethren with courageous

speeches; wha all cain and subseryvit.’ Such were the men who faced the

king in behalf of an independent rule for the kirk of Scotland.

At length there was a reaction

against the dominion of the two court favourites. A combination of nobles

of the ultra-Protestant party—the Earl of Gowrie, the Earl of Mar, Lord

Glammis, and others, laid a gentle compulsion on the young king while he

was staying at Ruthven House near Perth (August 1582), and his councillors

Lennox and Arran were debarred from his presence. After this event, known

in our history as the Raid of Ruthven, the king remained under the

control of his new councillors for a year, during which a pure

Presbyterianism was again encouraged, and the English alliance was

cultivated. The Duke of Lennox was forced to withdraw to France, where, to

the great grief of the king, he soon after contracted a sickness, and

died.

Regaining his liberty by stratagem,

James once more put himself under the guidance of the profligate but

energetic Arran. A modified episcopate was established in the church,

under a subordination to the state, and a restraint was imposed on the

tongues of the clergy in the pulpit. The Earl of Gowrie was brought to the

block. Several ministers, including Melville, had to take refuge in

England. But the general tendency of things in Scotland was inconsistent

with the rule of a man possessing the genius of Arran. Elizabeth, too,

deemed it best for her interests that others should have the control of

Scottish affairs. Accordingly, a new and more formidable combination was

formed. Joined by Lord John Hamilton, the head of the long proscribed

house of Hamilton, and by Lord Maxwell, whom Arran had offended, they

advanced with an army of 5000 men to Stirling, then the seat of the court.

Arran, unable to resist, fled, and was allowed to fall into obscurity. The

king with great placidity put himself into the hands of his new

councillors (November 1585). This coup d’etat was followed by the

restoration of the Hamilton family to its titles and estates.

1579

The young king having now assumed the government, and being about to make

his first visit to Edinburgh, the magistrates and citizens were anxious to

give him an honourable reception. There was immediately a great bustle

regarding the preparation of a silver cupboard and other pieces of plate

to be presented to him, as well as the getting of dresses suitable to be

worn by the chief men at the royal entry. There was even a deputation to

the High School, ‘to vesie the maister of the Hie Schule tragedies to be

made by the bairns, and to report;’ besides another ‘to speak the

Frenchman for his opinion in device of the triumph.’

All merchants stented to above ten

pounds were enjoined to have ‘everilk ane of them ane goune of fine black

camlet of silk of serge, barrit with velvet, effeiring his substance.’ All

stented to sixteen pounds, ‘to have their gounes of the like stuff, the

breists thereof linit with velvet, and begairit with coits of velvet,

damas, or sattin.’ The thirteen city-officers were to have each a livery

composed of three ells of English stemming to be hose, six quarters

of Rouen canvas to be doublets, with 13s. 4d. for passments, and a black

hat with a white string.

Another preparative was an edict,

that all manner of persons having cruives for swine under their

stairs or in common vennels, ‘and sic like as has middings and fulyie

collectit, or has tar barrels on the Hie Street, as also ony redd stanes

or timber on the said Hie Street or common vennels, remove the same.’

Pioneers, too, ‘to shool in the muck outwith the West Port.’ The

inhabitants to hang their stairs with tapestry and arras wark. The Privy

Council, on their part, proclaimed penalties against all who should come

with firearms, or any other armour than their swords and whingers.

Sep 30

The boy-king came from Stirling attended by about two

thousand men on horseback, and his reception in the city was quaintly

magnificent. ‘At the West Port he was receivit by the magistrates under a

pompous pall of purple velvet. That port presentit unto him the wisdom of

Solomon, as it is written in the thrid chapter of the first book of Kings;

that is to say, King Solomon was representit with the twa women that

contendit for the young child. This done, they presented unto the king,

the sword for the one hand, and the sceptre for the other. And as he made

further progress within the town, in the street that ascends to the Castle

there is an ancient port [the West Bow], at the whilk there hang a curious

globe that openit artificially as the king came by, wherein was a young

boy that descendit craftily, presenting the keys of the town to his

majesty, that were all made of fine massy silver; and these were presently

receivit by ane of his honourable council at his awn command. During this

space, Dame Music and her scholars exercisit her art with great melody.

Then in his descent [along the High Street], as he came foment the house

of Justice, there shew themselves unto him four gallant vertuous ladies;

to wit, Peace, Justice, Plenty, and Policie; and either of them had ane

oration to his majesty. Thereafter, as he came toward the chief collegiate

kirk, there Dame Religion shew herself, desiring his presence, whilk he

then obeyit by entering the kirk; where the chief preacher for that time

made a notable exhortation unto him for the embracing of religion and all

her cardinal vertues, and of all other moral vertues. Thereafter he came

forth, and made progress to the Mercat Cross, where he beheld Bacchus with

his magnifick liberality and plenty distributing of his liquor to all

passengers and beholders, in sic appearance as was pleasant to see. A

little beneath is a mercat place of salt, whereupon was paintit the

genealogy of the kings of Scotland, and a number of trumpets sounding

melodiously, and crying with loud voice, Welfare to the King! At

the east port was erectit the conjunction of the planets, as they were in

their degrees and places the time of his majesty’s happy nativity, and the

same vively representit by the assistance of King Ptolemy. And withal the

haill streets were spread with flowers, and the fore-houses of the

streets, by the whilk the king passit, were all hung with magnifick

tapestry, with paintit histories and with the effigies of noble men and

women. And thus he passed out of the town of Edinburgh, to his palace of

Halyroodhouse.’ - H. K. J.

Oct 20

The Estates passed an act against ‘strang and idle beggars,’ and ‘sic as

make themselves fules and are bards;' likewise against ‘the idle people

calling themselves Egyptians, or any other that feigns them to have

knowledge of charming, prophecy, or other abused sciences, whereby they

persuade the people that they can tell their weirds, deaths, and fortunes,

and sic other fantastical imaginations.’ The act condemns all sorts of

vagrant idle people, including ‘minstrels, sangsters, and tale-tellers,

not avowed in special service by some of the lords of parliament or great

burghs,’ and ‘vagabond scholars of the universities of St Andrews,

Glasgow, and Aberdeen.’ The same act made some provision for the genuine

poor, enjoining them all to repair to their native parishes and there live

in almshouses: a very nice arrangement for them, it must be owned; only

there were not any almshouses for them to live in.

Two poets hanged in August, and an

act of parliament against bards and minstrels in October; truly, it seems

to have been sore times for the tuneful tribe!

By this time, Arbuthnot’s edition of

the Bible was completed and in circulation. The gratification of the

clergy on seeing such a product of the native press, found eloquent

expression in an address of the General Assembly to the king (June 1579),

when they took occasion to praise the printer as ‘a man who hath taken

great pains and travel worthy to be remembered;’ and told how there should

henceforth be a copy in every parish kirk, to be called the Common Book of

the Kirk, ‘as the most meet ornament for such a place.’ ‘Oh what

difference,’ exclaimed these devout men, ‘between thir days of light, when

almost in every private house the book of God’s law is read and understood

in our vulgar language, and the age of darkness, when scarcely in a whole

city, without the cloisters of monks and friers, could the book of God

once be found, and that in a strange tongue of Latin, not good, but mixed

with barbarity, used and read by few, and almost understood and exponed by

none.’ All worldly wealth seemed vain and poor compared with this fountain

of spiritual comfort. ‘We ought,’ they said, ‘with most thankful hearts to

praise and extol the infinite goodness of God, who hath accounted us

worthy to whom He should open such an heavenly treasure.’—B.

U. K.

Nov 10

In that unmistrusting reliance on force for religious objects which marked

the age, it was enacted in parliament, that each householder worth three

hundred merks of yearly rent, and all substantious yeomen and burgesses

esteemed as worth five hundred pounds in land and goods, should have a

Bible and psalm-book in the vulgar tongue, under the penalty of ten

pounds. A few months later (June 16, 1580), one John Williamson was

commissioned under the privy seal to visit and search every house in the

realm, ‘and to require the sicht of their Bible and psalm-buke, gif they

ony have, to be marked with their awn name, for eschewing of fraudful

dealing in that behalf.’

The zeal of the clergy, their

self-denying poverty, their resoluteness in advancing their views of

church polity against court influence, have all been touched upon. Little

more than six hundred in number—for hundreds of the parishes had no

minister—they were indefatigable in their efforts to moralise the rude

mass of the community; although it was, by their own account, such as

might have appeared hopeless to other men; there being now, as they said,

an ‘universal corruption in the whole realm,’ ‘great coldness and

slackness’ even in the professors of religion, and a ‘daily increase of

all kinds of fearful sins and enormities, as incest, adulteries, murders,

. . . cursed sacrilege, ungodly sedition and division, . . . with all

manner of disorders and ungodly living.’

The picture which James Melville

gives of the four ministers of Edinburgh, then living in one house—where

the Parliament House now stands—is very interesting: ‘God glorified

himself notably,’ says he, ‘with that ministry of Edinburgh in these days.

The men had knawledge, uprightness, and zeal; they dwelt very commodiously

together, as in a college, with a wonderful concert in variety of gifts;

all strake on ae string, and soundit a harmony. John Dune was of small

literature, but had seen and marked the great warks of God in the first

Reformation, and been a doer baith with tongue and hand. He had been a

diligent hearer of Mr Knox, and observer of all his ways. He conceivit the

best grounds of matters wed, and could utter them fairly, fully, and

fearfully, with a mighty spreit, voice, and action. The special gift I

marked in him was haliness, and a daily and nightly careful, contiunal

walking with God in meditation and prayer. He

was a very gude fallow, and took delight, as

his special comfort, to have his table and house filled with the best men.

These he wald gladly hear, with them confer and talk, professing he was

but a book-bearer, and wald fain learn of them; and getting the ground and

light of knawledge in any guid point, then wald he rejoice in God, praise

and pray thereupon, and urge it with sae clear and forcible exhortation in

assemblies and pulpit, that he was esteemed a very furthersome instrument.

There lodgit in his house at all these assemblies in Edinburgh for common,

Mr Andrew Melville, Mr Thomas Smeaton, Mr Alexander Arbuthnot, three of

the learnedest in Europe; Mr James Melville, my uncle, Mr James Balfour,

David Ferguson, David Home, ministers; with some zealous, godly barons and

gentlemen. In time of meals was reasoning upon guid purposes, namely

matters in hand; thereafter qarnest and lang prayer; thereafter a chapter

read, and every man about [in turn] gave his note and observation thereof;

sae that, gif all had been set down in write, I have heard the learnedest

and best in judgment say, they wald not have wished a fuller and better

commentary nor [than] sometimes wald fall out in that exercise. Thereafter

was sung a psalm; after the whilk was conference and deliberation upon the

purposes in hand; and at night before going to bed, earnest and zealous

prayer according to the estate and success of matters. And oft times, yea

almost daily, all the college was together in sue or other of their

houses, &c.’

The picture which the same writer

gives of his uncle Andrew is full of fine touches. Andrew was principal of

the theological college (St Mary’s) at St Andrews; deeply learned,

logical, not arrogant for himself, but possessed of all that

disinterestedness and integrity which form the peculiar glory of Knox’s

character; to crown all, strenuous and fearless in the advocacy of his

views of religion and church-discipline. James describes him as remarkable

for patience and equal temper, where others were hot. Yet—’this I ever

marked to be Mr Andrew’s manner: Being sure of a truth in reasoning, he

wald be extreme hot, and suffer nae man to bear away the contrair, but

with reason, words, and gesture, he wald carry it away, caring for nae

person, how great soever they were, namely in matters of religion. And in

all companies at table and otherways, as he understood and took up the

necessity of the persons and matter in hand to require, he wald freely

and bauldly hald their ears fu’ of the truth; and, take it as they

wald, he wald not cease nor keep silence; yea, and not only anes or twice,

but at all occasions, till he fand them better instructed, and set, to go

forward in the good purpose.’

His ‘heroic courage and stoutness’

in advancing his own views, and resisting persons of authority set upon

establishing what he thought error, was equally remarkable. For

example—’The Regent [Morton], seeing he could not divert him by benefits

and offers, calls for him ae day indirectly, and after lang discoursing

upon the quietness of the country, peace of the kirk, and advancement of

the king’s majesty’s estate, he breaks in upon sic as were disturbers

thereof by their conceits and ower-sea dreams, imitation of Geneva

discipline and laws; and after some reasoning and grounds of God’s word

alledgit, whilk irritat the Regent, he breaks out in choler and boasting

[threatening] : "There will never be quietness in this country till half a

dozen of you be hangit or banishit the country." "Tush, sir," says Mr

Andrew, "I have been ready to give my life where it was not half sae wed

wared [spent], at the pleasure of my God. I lived out of your country ten

years as weel as in it. Let God be glorified, it will not lie in your

power to hang or exile his truth."’

1580, Apr

John Innes, of that Ilk, being childless, entered, in March 1577, into a

mutual bond of tailyie with his nearest relation, Alexander Tunes,

of Cromy, conveying to him his whole estate, failing heirs-male of his

body, and taking the like disposition from Cromy of his estate. There was

a richer branch of the family represented by Robert Innes, of Innermarky,

who pined to see the poorer preferred in this manner. So loud were his

expressions of displeasure, that ‘Cromy, who was the gallantest man of his

name, found himself obliged to make the proffer of meeting him single in

arms, and, laying the tailyie upon the grass, see if he durst take it

up—in one word, to pass from all other pretensions, and let the best

fellow have it.’

This silenced Innermarky, but did

not extinguish his discontent. He began to work upon the feelings of the

Laird of Innes, representing how Cromy already took all upon himself, even

the name of Laird, leaving him no better than a masterless dog—as

contemptible, indeed, as a beggar—a condition from which there could be no

relief but by putting the usurper out of the way. This he himself offered

to do with his own hand, if the laird would concur with him: it was an

unpleasant business, but he would undertake it, rather than see his chief

made a slave. By these practices, the weak bird was brought to give his

consent to the slaughter of an innocent gentleman, his nearest relation,

and whom he had not long before regarded with so much good-will as to

admit him to a participation of his whole fortune.

‘There wanted nothing but a

conveniency for putting their purpose in execution, which did offer itself

in the month of April 1580. At which time Alexander, being called upon

some business to Aberdeen, was obliged to stay longer there than he

intended, by reason that his only son Robert, a youth of sixteen years of

age, had fallen sick at the college, and his father could not leave the

place till he saw what became of him. He had transported him out of the

Old Town, and had brought him to his own lodgings in the New Town. He had

also sent several of his servants home from time to time, to let his lady

know the reason of his stay.

‘By means of these servants, it came

to be known perfectly at Kinnairdy in what circumstances Alexander was at

Aberdeen, where he was lodged, and how he was attended, which invited

Tunermarky to take the occasion. Wherefore, getting a considerable number

of assistants with him, he and Laird John ride to Aberdeen; they enter the

town upon the night, and about midnight came to Alexander’s lodging.

‘The outer gate of the close they

found open, but all the rest of the doors shut. They were afraid to break

up the doors by violence, lest the noise might alarm the neighbourhood;

but choiced rather to raise such a cry in the close as might oblige those

who were within to open the doors and see what it might be.

‘The feuds at that time betwixt the

families of Gordon and Forbes were not extinguished; therefore they raised

a cry as if it had been upon some outfall among these people, crying,

"Help a Gordon—a Gordon!" which is the gathering-word of the friends

of that family. Alexander, being deeply interested in the Gordons, at the

noise of the cry started from his bed, took his sword in hand, and opening

a back-door that led to the court below, stepped down three or four steps,

and cried to know what was the matter. Innermarky, who by his word knew

him, and by his white shirt discerned him perfectly, cocks his gun, and

shoots him through the body. In an instant, as many as could get about him

fell upon him, and butchered him barbarously.

‘Innermarky, perceiving, in the

meantime, that Laird John stood by, as either relenting or terrified, held

the bloody dagger to his throat, that he had newly taken out of the

murdered body, swearing dreadfully that he would serve him in the same way

if he did not as he did, and so compelled him to draw his dagger, and stab

it up to the hilt in the body of his nearest relation, and the bravest

that bore his name. After his example, all that were there behoved to do

the like, that all might be alike guilty. Yea, in prosecution of this, it

has been told me, that Mr John Innes, afterwards of Coxton, being a youth

then at school, was raised out of bed, and compelled by Innermarky to stab

a dagger into the dead body, that the more might be under the same

condemnation—a very crafty cruelty.

‘The next thing looked after was the

destruction of the sick youth Robert, who had lain that night in a bed by

his father, but, upon the noise of what was done, had scrambled from it,

and by the help of one John of Coloreasons, or rather of some of the

people of the house, had got out at an unfrequented back-door into the

garden, and from that into a neighbour’s house, where he had shelter, the

Lord in his providence preserving him for the executing of vengeance upon

these murderers for the blood of his father.

‘Then Innermarky took the dead man’s

signet-ring, and sent it to his wife, as from her husband, by a servant

whom he had purchased to that purpose, ordering her to send him such a

particular box, which contained the bond of tailyie and all that had

followed thereupon betwixt him and Laird John, whom, the servant said, he

had left with his master at Aberdeen, and that, for dispatch, he had sent

his best horse with him, and had not taken leisure to write, but sent the

ring.

‘Though it troubled the woman much

to receive so blind a message, yet her husband’s ring, his own servant,

and his horse, prevailed so with her, together with the man’s importunity

to be gone, that she delivered to him what he sought, and let him go.

‘There happened to be then about the

house a youth related to the family, who was curious to go the length of

Aberdeen, and see the young laird who had been sick, and to whom he was

much addicted. This youth had gone to the stable, to intercede with the

servant that he might carry him behind him; and in his discourse had found

the man under great restraint and confusion of mind, sometimes saying he

was to go no further than Kinnairdy (which indeed was the truth), and at

other times that he behoved to be immediately at Aberdeen. This brought

him to jalouse [suspect], though he knew not what; but further knowledge

he behoved to have, and therefore he stepped out a little beyond the

entry, watching the servant’s coming, and in the by-going suddenly leaped

on behind him, or have a satisfying reason why he refused him. The contest

became such betwixt them, that the servant drew his dirk to rid him of the

youth’s trouble, which the other wrung out of his bands, and downright

killed him with it, and brought back the box, with the writs and horse, to

the house of Innes (or Cromy, I know not which).

‘As the lady is in a confusion for

what had fallen out, there comes another of the servants from Aberdeen,

who gave an account of the slaughter, so that she behoved to conclude a

special hand of Providence to have been in the first passage. Her next

course was to secure her husband’s writs the best she could, and fly to

her friends for shelter, by whose means she was brought with all speed to

the king, before whom she made her complaint.’

The son of the murdered man was

taken under the care of the Earl of Huntly, who was his relation; but so

little apprehension was there of a prosecution for the murder, that

Innermarky, five weeks after the event, obtained from his chief a

disposition of the estate in his own favour. Two or three years after,

however, the young Laird of Cromy came north with a commission for the

avenging of his father’s murder, and the Laird of Innes and Innermarky

were both obliged to go into hiding. For a time, the latter skulked in the

hills, but, wearying of that, he got a retreat constructed for himself in

the house of Edinglassie, where he afterwards found shelter. Here young

Cromy surprised him in September 1584. The same young man who had killed

his servant was the first to enter his Patmos, for which venturesome act

he was all his life after called Craig-in-peril. Innermarky’s head

was cut off, and, it is said, afterwards taken by Cromy’s widow to

Edinburgh, and cast at the king’s feet. The Innermarky branch being thus

set aside, young Cromy succeeded in due time as Laird of Innes.—Hist.

Acc. Fam. Innes.

June 25

'. . . . being Saturday, betwixt three o’clock afternoon and Sunday’s

night thereafter, there blew such a vehement tempest of wind, that it was

thought to be the cause that a great many of the inhabitants of Edinburgh

contracted a strange sickness, which was called Kindness. It fell

out in the court, as well as sundry parts of the country, so that some

people who were corpulent and aged deceased very suddenly. It continued

with every one that took it three days at least.’—Moy. R.

July

The king being at St Andrews, on a progress with the Regent Morton, the

gentlemen of the country had a guise or fence to play before him.

‘The play was to be acted in the New Abbey. While the people is gazing and

longing for the play, Skipper Lindsay, a phrenitic man, stepped into the

place which was kept void till the players came, and paceth up and down in

sight of the people with great gravity, his hands on his side, and looking

loftily. He had a manly countenance, but was all rough with hair. He had

great tufts of hair upon his brows, and also a great tuft upon the neb of

his nose. At the first sight, the people laughed loud; but when he began

to speak he procured attention, as if it had been to a preacher. He

discoursed with great force of spirit, and mighty voice, exhorting men of

all ranks and degrees to hear him, and take example by him. He declared

how wicked and riotous he had been, what he had done and conquest

[acquired] by sea, how he had spended and abased himself on land, and what

God had justly brought upon him for the same. He had wit, he had riches,

he had strength and ability of body, he had fame and estimation above all

others of his trade and rank; but all was vanity that made him misken his

God. But God would not be miskenned by the highest. Turning himself to the

boss [empty] window, where the king and Aubigné was above, and Morton

standing beneath, gnapping upon his staff; he applied to him in special,

as was marvellous in the ears of the hearers; so that many were astonished

and some moved to tears, beholding and hearkening to the man. Among other

things, he warned the earl, not obscurely, that his judgment was drawing

near and his doom in dressing. And in very deed at the same time was his

death contrived. The contrivers would have expected a discovery, if they

had not known the man to be phrenitic and bereft of his wit. The earl was

so moved and touched at the heart, that, during the time of the play, he

never changed the gravity of his countenance, for all the sports of the

play.’—Cal.

Sep 9

One Arnold Bronkhorst, a Fleming, had found his way into Scotland, as one

of a group of adventurers who were disposed to make a new effort for the

successful working of the gold-mines of Lanarkshire. The account we have

of the party is obscure and traditional. One Nicolas Hilliard, goldsmith

in London, and minature-painter to Queen Elizabeth, is said to have

belonged to it, and to have brought Bronkhorst as his servant or

assistant. The story is, that, being disappointed of a patent for the

mines from the Regent Morton, Bronkhorst was glad at last to remain about

the Scottish court as portrait-painter to the king. He certainly did serve

the king in that capacity, as we have an account of his paid at this date,

to the amount of £64, for three specimens of his art—namely, ‘Ane portrait

of his majesty fra the belt upward,’ ‘ane other portrait of Maister George

Buchanan,’ and ‘ane portrait of his majesty full length,’ beside a gift of

a hundred merks, ‘as ane gratitude for his repairing to this country.’ A

twelvemonth later, King James constituted him his own painter for his

lifetime, ‘with all fees, duties, and casualties, usit and wont.'

Sep 20

In the midst of the strange phantasmagoria of rudeness and murderous

violence on the one hand, and exalted religious zeal on the other, which

now passes before us, we find that industrious men were prosecuting useful

merchandise at home and abroad, but under painful risks imposed by the

general neglect of the laws of health. Witness the following little

episode. John Downie’s ship, the William, on her return with a

cargo from Danskein [Dantzig], enters the Firth of Forth. Seven merchants

of Edinburgh, and some from other towns, are in this vessel, returning

from foreign parts, where they have been upon their lawful business. All

are doubtless full of pleasant anticipations of the home-scenes which they

expect to greet them as soon as they once more set foot on their native

soil. Alas! the pest breaks out in the vessel, and sundry of these poor

citizens are swept off. The captain dare not approach the shore, but must

wait the orders which the authorities may send him. There is immediately a

meeting of the Privy Council, at which an order goes forth that the

survivors in John Downie’s ship shall land on the uninhabited island

called St Colm’s Inch in the Firth of Forth, and there remain till

‘cleansed,’ on pain of death, and no one to traffic with them under the

same penalty.

The chief chapter of this sad story,

so characteristic of the time, is told in few words by Moysie: ‘There were

forty persons in the ship, whereof the most part died.’

On the 27th of November we have a

pendant to the tale of the plague-ship. Downie the skipper is dead,

leaving a widow and eleven children. James Scott and David Duff; mariners,

are also dead, the former leaving a widow and seven children. Several of

the passengers are also dead, while the others are pining on the lonely

islands of Inchkeith and Inch Garvie. The ship, with its cargo unbroken,

is riding at St Colm’s Inch, and beginning to leak, so that much property

is threatened with destruction. In these circumstances, the Privy Council,

on petition, enacted that orders should be taken, as far as consistent

with the public safety, for the preservation of the vessel.

Oct

Lord Ruthven and Lord Oliphant were at feud, in consequence of a dispute

about teinds. The former, on his return from Kincardine, where he had been

attending the Earl of Mar’s marriage, passed near Lord Oliphant’s seat of

Dupplin, near Perth. This was construed by Oliphant into a bravado on the

part of Ruthven. His son, the Master of Oliphant, accordingly came forth

with a train of armed followers, and rode hastily after Lord Ruthven. The

foremost of Ruthven’s party, taking a panic, fled in disorder,

notwithstanding their master’s call to them to stay. He was then obliged

to fly also; but his kinsman, Alexander Stewart, of the house of Traquair,

stayed to try to pacify the Oliphant party. He was shot with a harquebuss

by one who did not know who he was, to the great grief of the Master.

Lord Ruthven prosecuted the Master

for this outrage. The Earl of Morton, out of regard to Douglas of

Lochleven, whose son-in-law Oliphant was, gave his influence on that side,

and thus incurred some odium, which probably helped to bring about his

destruction soon after—Cal.

Oct 20

In a General Assembly held at Edinburgh, an order was issued to execute

the acts of the kirk upon apostates, and let them be punished as

adulterers; ‘perticularly that the Laird of Dun execute this act upon

the Master of Gray, an apostate now returned to Scotland. It being

reported to the king that the Master of Gray his house did shake and rock

in the night as with an earthquake, and the king [then fourteen years old]

interrogating David Fergusson [minister of Dunfermline], "What he thought

it could mean that that house alone should shake and totter?" he answered:

(‘Sir, why should not the devil rock his awn bairns?"'

An earthquake, noted in Howes’s

Chronicle as having been experienced in Kent at midnight of the 1st of

May this year, was is probably the cause of the rocking felt at the Master

of Gray’s house. In Kent it made ‘the people to rise out of their beds and

run to the churches, where they called upon God by earnest prayers to be

merciful to them.’

George Auchinleck of Balmanno had

been one of the confidants of the Regent in the days of his power. It

being well known that he had influence in bringing about the decision of

lawsuits, the highest nobility were glad at that time to pay court to him.

As an illustration of the nature of his position—Coming one day from the

Regent’s house at Dalkeith to Edinburgh, and walking up the High Street,

he met one Captain Nesbit, with whom he had some slight quarrel, and

drawing his sword, instantly thrust him through the body, so that he was

left for dead? So far from seeking concealment after this violence,

Auchinleck held straight on to the Tolbooth, where the Court of Session

sat, as though he had done no wrong; after which he coolly made his way

back to the Regent’s court at Dalkeith. It does not appear that he was in

any way punished for stabbing Nesbit.

On another occasion, as Auchinleck

stood within the bar of the Tolbooth, an old man of unprosperous

appearance made his way through the crowd, asking permission to speak with

him. When Auchinleck turned to ask what he wanted, the old man said: ‘I am

Oliver Sinclair!’ and without another word, turned and went away. It was

the quondam favourite of James V., now a poor and dejected gentleman,

albeit connected by near ties with some of the greatest men in the

country. Men talked much of this proceeding of Sinclair: it seemed to them

equivalent to his saying: ‘Be not too proud of your interest at court. I

was once as you are; you may fall to be as I am.’—H of G.

Dec 12

The prediction was now verified, for, Morton being now out of power and in

danger of his life, Auchinleck no longer had influence at council or in

court. He, moreover, stood in no small personal danger from his many

enemies. As he was walking on the High Street of Edinburgh, he was beset

at a passage near St Giles’s Church by William Bickerton of Casch, and

four other gentlemen, who assailed him with bended pistols, by one of

which he was shot through the body, after which he was left for dead. This

was thought to be done in revenge for an attack by him upon Archibald, the

brother of William Bickerton. The assailants were all found guilty of the

slaughterous attempt, but without the aggravation of its being done within

three-quarters of a mile of the king’s person, seeing that ‘the king’s

majesty was furth at the hunting, the time of the committing thereof.’—Pit.

Auchinleck survived this accident,

and we find him in the ensuing March in the hands of the Earl of Arran,

and put to the torture, in order to extort from him a confession of

certain crimes with which he was charged, but which he denied. He took a

part in the affair of the Raid of Ruthven in August 1582. When the Earl of

Arran on that occasion, hearing of the king’s being secluded in Ruthven

House, came to try if he could gain access to him, ‘the Earl of Gowrie met

him at the gate, and had straightway killed him, if George Auchinleck had

not held his hand as he was about to have pulled out his dagger to have

stabbed him.’—H. of G.

1581, Jan 28

A Confession of Faith was this day subscribed by the king, his household

and courtiers, including Lennox, and many of the nobility and other

persons, professing ‘the religion now revealed to the world by the

preaching of the blessed evangel,’ and solemnly abjuring all the doctrines

and practices of the Romish Church.’

Jan 29

This day, Sunday, there were gay doings in the boy-king’s court of

Holyrood, namely, running at the ring, justing, and such-like pastimes,

besides sailing about in boats and galleys at Leith.—Cal.

The reader must not be too much

surprised at this occurring the day after the signing of a solemn

confession of the Protestant faith. The truth seems to have been this: the

signers signed under the pressure of a party they had some interest for

the moment in gratifying or blinding, and the accepters of the document

were content with the fact of the signing, without regard to the too

probable hypocrisy under which it took place. It is not uncommon for

professions to be only a symptom of the reality of the opposite of what is

professed.

Mar 11

The ex-Regent now lay a hopeless prisoner in Dumbarton Castle, chiefly

occupied, we are told, in reading the Bible, which, though he had forced

the people to buy it under a penalty, he had hitherto much neglected

himself. One of his servants, named George Fleck, ‘was apprehended in

Alexander Lawson’s house [in Edinburgh], together with the said Alexander,

not without their own consents, as was alleged, to reveal where the Earl

of Morton’s treasure lay. The bruit [rumour] went---when the booth were

presented to George Fleck, that he revealed a part of the treasure to be

lying in Dalkeith yard, under the ground; a part in Aberdour, under a

braid stone before the gate; a part in Leith. Certain it is, he [the earl]

was the wealthiest subject that had been in Scotland for many years.’—Cal.

Sir James Melville tells us that,

long before the trial of Morton, his gold and silver were transported by

his natural son, James Douglas, and one of his servants called John

Macmoran. ‘It was first carried in barrels, and afterwards hid in some

secret parts; part was given to be kept by some who were looked upon as

his friends, who made ill account of it again; so that the most part

thereof lighted in bad hands, and himself was so destitute of money, that

when he went through the street to the Tolbooth to undergo his assize, he

was compelled to borrow twenty shillings to distribute to the poor, who

asked alms of him for God’s sake.’

In May, he ‘was brought to

Edinburgh, and kept in Robin Gourlay’s house, ’with a band of men of

weir.’ James Melville says: ‘The very day of his putting to assize, I

happened to be in Edinburgh, and heard and saw the notablest example,

baith of God’s judgment and mercy that, to my knowledge, ever fell out in

my time. For in that Tolbooth, where oftentimes, during his government, he

had wrested and thrawn judgment, partly for gain, whereto he was given,

and partly for particular favour, was his judgment overthrown; and he wha,

above any Scotsman, had maist gear, friendship, and cliental, had nane to

speak a word for him that day; but, the greatest part of the assizers

being his knawn unfriends, he was condemned to be headit on a scaffold,

and that head, whilk was sae witty in warldly affairs and policy, and had

commanded with sic authority and dignity within that town and

judgment-seat, to be set upon a prick upon the hichest stane of the gable

of the Tolbooth that is towards the public street.’

Morton was condemned for being ‘airt

and part' concerned in the murder of Darnley. He was more clearly an actor

in the cruel slaughter of Riccio. After doing his best to insnare Mary

into a marriage with Bothwell, he had headed a rebellion against her on

hypocritical pretences. The extortions he had practised during his

regency, in order to enrich himself, shewed an equally sordid and cruel

character. Throughout all the time of his government, he had outraged

decency by the grossness of his private life. Yet ‘he had great comfort

that he died a Christian, in the true and sincere profession of religion,

whilk he cravit all the faithful to follow, and abide thereat to the

death.’—Moy. ‘He keepit the same countenance, gesture, and short

sententious form of language upon the scaffold, whilk he usit in his

princely government. He spake, led about and urgit by the commanders at

the four nooks of the scaffold; but after that ance he had very fectfully

and gravely uttered, at guid length, that whilk he had to speak,

there-after almaist he altered not thir words: "It is for my sins that God

has justly brought me to this place; for gif I had served my God as truly

as I did my king, I had not come here. But as for that I am condemned for

by men, I am innocent, as God knows. Pray for me." . . . . I [am] content

to have recordit the wark of God, whilk I saw with my ees and heard with

my ears.’— Ja. Mel.

‘After all was done, he went without

fear and laid his neck upon the block, crying continually "Lord Jesus,

receive my spirit," till the axe of the Maiden—which he himself had caused

make after the pattern which he bad seen at Halifax in Yorkshire— falling

upon his neck, put an end to his life and that note together. His body was

carried to the Tolbooth, and buried secretly in the night in the

Greyfriars. His head was affixed on the gate of the city.’—H.

of G.

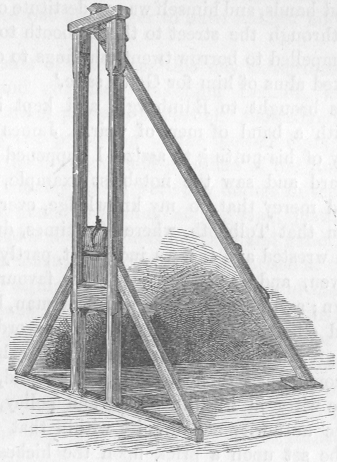

The Maiden

The Maiden, which still exists in

the Museum of the Society of the Antiquaries of Scotland, is an instrument

of the same nature as the guillotine, a loaded knife running in an upright

frame, and descending upon a cross-beam, on which the neck of the culprit

is laid. It is not unlikely that the ex-Regent introduced the Maiden; but

another allegation, which asserts him to have been the first to suffer by

it, is untrue.

At the death of Morton, the common

people were much occupied in discussing a prophecy that the Bleeding Heart

should fall by the Mouth of Arran. Morton, as a Douglas, bore the Bleeding

Heart in his coat-armorial. Captain Stuart having been made Earl of Arran

between the time of the accusation and the execution, here, said they, is

the prediction realised, though what the Mouth of Arran meant it would

have puzzled them to tell. It was probably to this unintelligible stanza

in the prophecies of Merling that they referred:

In the mouth of Arran an selcouth

shall fall,

Two bloody harts shall be taken with a false train,

And derfly dung down without any dome,

Ireland, Orkney, and other lands many,

For the death of those two great dule shall make.

Morton may be taken as an example of

a class of public men in that rude and turbulent time, who were to all

appearance earnest Christians of the reforming and evangelical stamp, and

nevertheless allowed themselves a licence in every wickedness, even to

treachery and murder, whenever they had a selfish object in view, or, more

strangely still, when the interests of religion, in their view of the

matter, called on them so to act.

Nothing is more remarkable in the

history of this period than the coincidence of wicked or equivocal actions

and pious professions in the same person. Adam Bothwell, Bishop of Orkney,

who performed the marriage-ceremony of Mary and Bothwell, and afterwards

in the basest manner took active part against her— who was in constant

trouble with the General Assembly on account of his shortcomings - writes

letters full of expressions of Christian piety and resignation. He is

constantly ‘saying with godly Job, gif we have receivit guid out of the

hand of the Lord, why should we not alsae receive evil—giving him maist

hearty thanks therefore, attesting our godly and stedfast faith in him,

whilk is maist evident in time of probane.’ Sir John Bellenden,

justice-clerk, who had a share in the murder of Signor David, and who, on

receiving a gift of Hamilton of Bothwell-haugh’s estate of Woodhouselee

from the Regent Moray, turned Hamilton’s wife out of doors, so as to cause

her to run mad—this vile man, in his will, speaks of ‘my saul, wha baith

sall meet my Maister with joy and comfort, to hear that comfortable voice

that he has promisit to resotat [resuscitate], saying, Come unto me thou

as ane of my elect.’

1581, June 11

An entry in the Lord Treasurer’s books reveals the mood of the gay king

and his courtiers, nine days after the bloody end of Morton. It is Sunday,

and James is residing with the Duke of Lennox at Dalkeith Castle. He

attends the parish church within the town, and, after service, returns,

with two pipers playing before him.

It was, however, only four days

after the death of Morton, and while his blood was still fresh upon the

streets, that the man who had brought him to the block passed through the

gay scenes of a marriage. Captain Stuart—for Scottish history can scarcely

be induced to recognise him as Earl of Arran—had formed a shameful

connection with a lady of high birth and rank now figuring at the Scottish

court. Born Elizabeth Stewart, as daughter of the Earl of Athole, she had

first been wife of Lord Lovat—then, after his death, wife of the Earl of

March, brother of the Regent Lennox. Her intrigue with Captain James, her

divorce of the Earl of March on alleged reasons which history would blush

to mention, her quick-following marriage to Arran while in a condition

which would have given her husband a plea of divorce against herself, and

this occurring so close to the time when Arran had shed the blood of his

great enemy, form a series of events sufficient to mark the character of

the court into which the young king had emerged from the strictness of

Presbyterian rule. When the lady brought her husband a son in the

subsequent January, the king was invited to the baptism, and we only learn

that he was prevented from attending in consequence of a temporary quarrel

which had by that time taken place between Lennox and Arran. [A

note-worthy anecdote of this lady is stated in Anderson’s History of

the Family of Fraser. On the death of her first husband, the tutorship

of her infant son, Lord Lovat, became a matter of contention between the

child’s grand-uncle, Fraser of Struie, and his uncle Thomas; and it seemed

likely there would be a fight between their various partisans. In these

circumstances, a clerical gentleman of the clan, Donald Fraser Dhu,

entreated the widow to interfere, and ask Struie to retire. She gave an

evasive reply, remarking that whatever might befall, ‘not a drop of

Stewart blood would be spilt.’ The mediator then drew his dirk, and told

her ladyship with a fierce oath, that her blood would be the first

that would be spilt, if she did not do as he requested. She then complied,

and Thomas, the child’s uncle, was accordingly elected as tutor.]

A contemporary writer, speaking of

the countess, calls her ‘the maistresse of all vice and villany,’ and says

she ‘infectit the air in his Hieness’ audience.’ He accuses her of

controlling the course of justice, and alleges that she ‘caused sundrie to

be hanged that wanted their compositions, saying: What had they been doing

all their days, that had not so much as five punds to buy them from the

gallows?’—Cal.

The Presbyterian clergy regarded the

frivolity of Lennox and Mombirneau, their foreign vices and oaths, joined

to the coarser native profligacy of Arran and his lady, as forming a bad

school for the young king. A love of amusement and buffoonery he certainly

contracted from this source; but it is remarkable that he was not drawn

into any gross vice by the bad example set before him.

Nov

At this time, upwards of twenty years after the Reformation, it was still

found that ‘the dregs of idolatry’ existed in sundry parts of the realm,

‘by using of pilgrimage to some chapels, wells, crosses . . . ., as also

by observing of the festival-days of the sancts, sometime namit their

patrons; in setting furth of bane-fires, [and] singing of carols within

and about kirks at certain seasons of the year.’ An act of parliament was

now passed, condemning these practices, and imposing heavy fines on those

guilty of them; failing which, the transgressors to endure a month’s

imprisonment upon bread and water.

1582, June

The archbishopric of Glasgow being vacant, Mr Robert Montgomery accepted

it from the king, on an understanding with the king’s favourite, the Duke

of Lennox, as to the income. The church excommunicated him. In Edinburgh,

‘he was openly onbeset [waylaid] by lasses and rascals of the town, and

hued out by flinging of stones at him, out at the Kirk of Field port, and

narrowly escaped with his life.’—Moy.

Sep 4

One consequence of the coup d’etat at Ruthven was the return of

John Dune from the banishment into which he had gone in May, to resume his

ministry in Edinburgh. The affair makes a fine historic picture.

‘As he is coming from Leith to

Edinburgh, there met him at the Gallow Green two hundred men of the

inhabitants of Edinburgh. Their number still increased till he came within

the Nether Bow. There they began [with bare heads and loud voices] to sing

the 124th psalm—"Now Israel may say, and that truly," &c., in four parts

[till heaven and earth resounded]. They came up the street to the Great

Kirk, singing thus all the way, to the number of two thousand. They were

much moved themselves, and so were the beholders. The Duke [of Lennox, who

was lodged in the High Street, and looked out and saw], was astonished and

more affrayed at that sight than at anything that ever he had seen before

in Scotland, and rave his beard for anger. After exhortation made in the

reader’s place by Mr James Lowson, to thankfulness, and the singing of a

psalm, they dissolved with great joy.’—Cal.

Sep 5

Another consequence of the change at court was, that the Duke of Lennox

was forced to leave the kingdom. The Presbyterian historians relate the

manner of his departure with evident relish. ‘The duke departed out of the

town, after noon, accompanied with the provost, bailies, and five hundred

men. . . . . He rode towards Glasgow, accompanied by the Lord Maxwell, the

Master of Livingstone, the Master of Eglintoun, Ferniehirst, and sundry

other gentlemen.' . . . . He ‘remained in Dunbarton at the West Sea,

where, or [ere] he gat passage, he was put to as hard a diet as he caused

the Earl of Morton to use there; yea, even to the other extremity that he

had used at court; for, whereas his kitchen was sae sumptuous that lumps

of butter was cast in the fire when it soked [grew dull], and twa or three

crowns waired upon a stock of kale dressing, he was fain to eat of a

meagre guse, scoudered with beare strae.’

1582, Sep 25

Died in Edinburgh, George Buchanan, at the age of seventy-eight,

immediately after concluding his History of Scotland. His high

literary accomplishments, especially his exquisite Latin composition, have

made his name permanently famous. His personal character was not without

its shades, yet it stands forth amidst the rough scenes of that time as

something, on the whole, venerable. Sir James Melville, in noting that,

while acting as one of the king’s preceptors, he kept the young monarch in

great awe, goes on to speak of him as ‘a stoic philosopher,’ who did not

act in that capacity with any view to his worldly interests. ‘A man of

notable endowmenth for his learning and knowledge in Latin poesy,’ says

this mild contemporary, ‘much honoured in other countries, pleasant in

conversation, rehearsing at all occasions moralities short and

instructive, whereof he had abundance, inventing where he wanted. He was

also religious, but was easily abused, and so facile, that he was led by

every company that he haunted, which made him factious in his old days,

for he spoke and wrote as those who were about him informed him; for he

was become careless, following in many things the vulgar opinion; for he

was naturally popular, and extremely revengeful against any man who had

offended him, which was his greatest fault. For he did write despiteful

invectives against the Earl of Monteith, for some particulars that were

between him and the Laird of Buchanan. He became the Earl of Morton’s

great enemy, for that a nag of his chanced to be taken from his servant

during the civil troubles, and was bought by the Regent, who had no will

to part with the said horse, he was so sure-footed and so easy, that

albeit Mr George had ofttimes required him again, he could not get him.

And, therefore, though he had been the Regent’s great friend before, he

became his mortal enemy, and from that time forth spoke evil of him in all

places, and at all occasions.’

A little while before Buchanan’s

death, while his history was passing through the press of Alexander

Arbuthnot in Edinburgh, the Rev. James Melville, accompanied by his uncle

Andrew, came from St Andrews ‘anes-errand ‘—that is, on set purpose—to see

him and his work. ‘When we came to his chalmer,’ says Melville, ‘we fand

him sitting in his chair, teaching his young man that servit in his

chalmer, to spell, a, b, ab; e, b, eb; &c. After salutation, Mr Andrew

says: "I see, sir, ye are not idle." "Better this," quoth he, "nor

stealing sheep, or sitting idle, whilk is as ill." Thereafter he shew[s]

us the Epistle Dedicatory to the King; the whilk when Mr Andrew had read

he tauld him it was obscure in some places, and wanted certain words to

perfite the sentence. Says he: "I may do nae mair for thinking on another

matter." "What is that?" says Mr Andrew. "To die," quoth he; "but I leave

that and mony mae things for yon to help."

‘We went from him to the printer’s

wark-house, whom we fand at the end of the 17 buik of his chronicle, at a

place whilk we thought very hard for the time, whilk might be an occasion

of staying the hail wark, anent the burial of Davia. [He states that David

Riccio was buried by the queen in the royal vault, ‘almost in the arms of

Magdalene Valois,’ and thence draws a shameful inference against the

chastity of Mary. To dedicate to the young king a book in which he

endeavoured to prove his mother an adulteress, and the murderer of her

husband, gives a strange idea of the sense of that age regarding the rules

of good taste, to say nothing more.] Thereafter, staying the printer from

proceeding, we came to Mr George again, and fand him bedfast by [contrary

to] his custom; and asking him how he did—"Even going the way of weelfare,"

says he. Mr Thomas, his cousin, shews him the hardness of that part of his

story, [and] that the king might be offended with it, and it might stay

all the wark. "Tell me, man," says he, "gif I have tauld the truth?"

"Yes," says Mr Thomas, "sir, I think sae." "I will bide his feid, and all

his kin’s then," quoth he: "pray, pray to God for me, and let Him direct

all."’

The sternness of Scottish prejudices

here reaches the heroic.

With its eight centuries of fable in

the front, and its glaring partisanship in the latter part, we cannot now

attach much importance to Buchanan’s history. Yet in respect of its

literary character, it contains some truly felicitous touches, as where he

describes the surface of Galloway in four words—’ in modicos colles

tumet;’ or the remarkable sea-board of Fife in two— ‘oppidulis

praecingitur.’ Expressions like these shew the master of literary art.

Dec 10

The king’s new councillors of course felt that hard measure had been dealt

to the ex-Regent. At this date, ‘the Earl of Morton’s head was taken down

off the prick which is upon the high gavell of the Tolbooth, with the

king’s licence, at the eleventh hour of the day; was laid in a fine cloth,

convoyed honourably, and laid in the kist where his body was buried. The

Laird of Carmichael carried it, shedding tears abundantly by the way.’—Cal.

1582-3, Jan 23

While the king was in the hands of the Ruthven conspirators, two gentlemen

came as ambassadors from France to see what could be done for him, and

were of course treated with little civility by the royal councillors. The

second, M. de Menainville, must have been the less acceptable to them, if

it was true which was alleged, that he had been one of the chief devisers

of the league in Picardy against the Protestants. With some difficulty, De

Menainville made his way into the royal presence at Holyroodhouse. ‘After

some words spoken to the king, he craved that he might be used as an

ambassador; that, as he had the use of meat and drink for his body, so he

might have food for his soul, meaning the mass, otherwise he would not

stay to suffer his most Christian prince’s authority and ambassage to be

violated. The king rounded [whispered] and prayed him to be sober in that

point, and all would be weel.’ It was not likely that the concession which

had been sternly refused to Queen Mary would, at such a time, be granted

to him. The king, with much ado, prevailed upon the magistracy of

Edinburgh to give the other ambassador, the Sieur de la Motte Fenelon, a

banquet on the eve of his departure. The kirk-session opposed the

entertainment; and when they found they could not prevent it, they did the

next best—held a solemn fast, with preachings and psalm-singing, during

the whole time of the feast—namely, from betwixt nine and ten in the

morning till two in the afternoon. The ministers called the banquet a

holding fellowship with ‘the murderers of the sanets of God.’—Cal.

Mar 28

De Menainville remained for some time after. ‘Upon Thursday the 28th of

March, commonly called Skyre Thursday, [he] called into his lodging

thirteen poor men, and washed their feet according to the popish manner,

whereat the people was greatly offended.’—

Cal.

Aug 23

All previous efforts at the finding of metals in the country having

failed, a contract was now entered into between the king and one

Eustachius Roche, described as a Fleming and mediciner, whereby the latter

was to be allowed to break ground anywhere in search of. those natural

treasures, and to use timber from any of the royal forests in furthering

of the work, without molestation from any one, during twenty-one years, on

the sole condition that he should deliver for his majesty’s use, for every

hundred ounces of gold found, seven ounces; and for the like weight of all

other metals - as silver, copper, tin, or lead—ten ounces for every

hundred found, and sell the remainder of the gold for the use of the state

at £22 per ounce of utter fine gold, and of the silver at 50s. the ounce.—P

C. R.

We light upon Eustachius again on

the 3d of December 1585, and he is then in no pleasant plight with his

mines. Assisted by a number of Englishmen, he had done his best to fulfil

his share of the contract, but ‘as yet he has made little or nae profit of

his travel, partly by reason of the trouble of this contagious sickness,

but specially in the default of his partners and John Scolloce their

factor,’ who would not fulfil either their duty to his majesty or their

engagements to himself. Through these causes, ‘the hail wark has been

greatly hinderit.’ He had Scolloce warded in Edinburgh; but he, ‘by his

majesty’s special command, is latten to liberty, without ony trial taken.’

At the same time, the king’s treasurer ‘has causit arreist the leid ore

whilk the complener has presently in Leith, and whilk was won in the mines

of Glengoner Water and Winlock.’ This was the greater hardship, as it was

the part he had to set aside for the Earl of Arran, in virtue of a

contract for the protection of his lordship’s rights to certain

lead-mines. The Lords were merciful to the poor adventurer, and ordered

the arrestment to be discharged.—P. C.

R.

He rises once more before us in a

new capacity under September 4, 1588.

Sep 10

The king having now escaped from his Ruthven councillors and fallen once

more under the influence of the Earl of Arran, Sir Francis Walsingham came

as Elizabeth’s ambassador to express her concern about these movements,

and see what could be done towards opposite effects. Coming to a king with

an unwelcome message has never been a pleasant duty; but it must have been

particularly disagreeable on this occasion, if it be true, as is alleged

by a Presbyterian historian, that Arran—who, says he, within a few days

after his return to court, ‘began to look braid ‘—hounded out a low woman,

called Kate the witch, to assail the ambassador with vile speeches

as he passed to and from the king’s presence. She was, it is alleged,

hired by Arran ‘for a new plaid and six pounds in money, not only to rail

against the ministry [clergy], his majesty’s most assured and ancient

nobility, and lovers of the amity [English alliance], but also set in the

entry of the king’s palace, to revile her majesty’s ambassador at

Edinburgh, St Andrews, Falkland, Perth, and everywhere, to the great grief

of all good men, and dishonour of the king and country.’ It is further

stated, that, being imprisoned ‘for a fashion,’ large allowance was made

for her entertainment, and she was relieved as soon as Walsingham had

departed.—Cal.

1583-4, Jan 9

While the kirk was beginning to feel the consequences of the king’s

emancipation from the Ruthven lords, it sustained an assault, though of a

very petty character, from a different quarter. Robert Brown, a Cambridge

student, had three years before attracted attention in Norfolk by his

novel and startling ideas regarding ecclesiastical matters. The Bishop of

Norwich imprisoned him, with the usual non-success as far as the

correction of opinion was concerned. He had then taken refuge at

Middleburgh, and there given forth his notions to the world in the form of

a pamphlet. Now he was come to Scotland, perhaps thinking it a pity that a

people should be in trouble between the contending claims of Prelacy and

Presbytery, when he could shew them that both systems were wrong. Landing

at Dundee, where, it is said, he received some encouragement, he advanced

by St Andrews to Edinburgh, and there took up his quarters ‘in the head of

the Canongate,’ along with four or five English followers, who were

accompanied by their wives and children. The people—who, for the most

part, were passionately attached to the simple fabric of their national

church, and dreamt of no rivalship or enmity to it except in

episcopacy—how they must have felt at the novel sight of a group of men

who, in declaring against bishops, also found fault with sessions and

synods, with indeed all ecclesiastical action whatever, considering each

congregation independent in itself, and no member of it less entitled to

pray and preach than the pastor!

Brown, whose self-confidence in

asserting his peculiar doctrines was very great, did not rest four days in

Edinburgh before he had presented himself to the general kirk-session for

a wrangle. We are told by a Presbyterian historian—he ‘made shew, in an

arrogant manner, that he would maintain that witnesses at baptism was not

a thing indifferent, but simply evil. But he failed in the probation.’ A

week after, ‘in conference with some of the presbytery, he alleged that

the whole discipline of Scotland was amiss; that he and his company were

not subject to it, and therefore he would appeal from the kirk to the

magistrate.’ Considering how the clergy stood with the court, this must

have been a most offensive threat; the more so that the court had already

shewn some symptoms of favour to Brown, in order to ‘molest the kirk.’ ‘It

was thought good that Mr James Lowson and Mr John Davidson should gather

out of his book such opinions as they suspected or perceived him to err

in, and get them ready, to pose him and his followers thereupon, that

thereafter the king might be informed.’ A week later, Brown and his

‘complices’ came before the presbytery, to answer the articles prepared

against him. We only further learn that he left Edinburgh, ‘malcontent,

because his opinions were not embraced, and that he was committed to ward

a night or two till they were tried’ (Cal.), a form of religious

disputation highly characteristic of the age. Brown afterwards, when

founding his sect of Independents in England, published a volume

containing various invectives against the Scottish kirk and its leaders,

of which Dr Bancroft took advantage in preaching against presbytery (9th

February 1589), while probably ready to consign their author to the pains

which the Bishop of Peterborough actually meted out to him by

excommunication.

1584

Thomas Vantrollier, a French Protestant, who had come to England early in

Elizabeth’s reign, migrated about this time to Edinburgh, where he set up

a printing-press. From his office proceeded this year a small volume of

poems, composed by the young king, under the title of The Essayes of a

Prentise in the Divine Art of Poesie; to which was added a prose

treatise embracing the ‘rules and cautels for Scottish poesie:’ a volume

of which it may be enough to say, that it betrays a laudable love of

literature in the royal author, joined to some power of literary

expression. Vantrollier does not appear to have met with sufficient

encouragement to induce him to remain in Edinburgh, as he soon after

returned to London.

July

At the end of this month, the pest was brought into Scotland at Wester

Wemyss, a small port in Fife—’ where many departed.’—Moy.

King James tells us in his

Basilicon Doron, that ‘the pest always smiths the sickarest such as

flies it furthest and apprehends deepliest the peril thereof.’ See his own

conduct on this occasion. About the end of September, while he was hunting

at Ruthven, ‘word came that there were five or six houses in Perth

affected with the plague, where his majesty’s servants were for the time.

Whereupon, his majesty departed the same night, with a very small

train to Tullibardine, and next day to Stirling, leaving his whole

household servants enclosed in the place of Ruthven, with express command

to them not to follow, nor remove forth of the same, until they saw what

became of them upon the suspicion.’—Moy.

R.

The pest on this occasion remained

in Perth for several months, working great destruction. It was ordained by

the kirk-session, May 24, 1585, that ‘hereafter during the time of the

plague, no banquets should be at marriages, and no persons should resort

to bridals under pain of ten pounds . . . . forty pounds to be paid by

them that call more than four on the side to the banquet, or bridal,

during the pest.’

In the ensuing February, under an

apprehension about the arrival of the pestilence in their city, the

town-council of Edinburgh adopted a highly rational sanitary measure,

ordering the ashes, dust, and dirt of their streets to be put up to

auction. We do not learn that any one undertook to pay for the privilege

of cleaning the streets of the capital, and Maitland remarks in his

history, that many years elapsed before the movement was renewed, not to

say carried into effect.

Dec 2

'.... baxter’s boy, called Robert Henderson—no doubt by the instigation of

Satan—desperately put some powder and a candle in his father’s

heather-stack, standing in a close opposite to the Tron of Edinburgh [the

public weighing-machine], and burnt the same, with his father’s house,

which lay next adjacent, to the imminent hazard of burning the whole town.

For which, being apprehended most marvelously, after his escaping out of

the town, he was on the next day burnt quick at the Cross, as an

example.’— Moy. R.

1585, Apr 7