|

MARY remained a prisoner in

Lochleven Castle for ten months, while Moray, as Regent, maintained a good

understanding with England, and did much to enforce internal peace and

order. At length (May 1568), the unhappy Queen made her escape, and threw

herself into the arms of the powerful family of Hamilton, who had

continued unreconciled to the new government. They raised for her a

considerable body of retainers, and for a few days she seemed to have a

chance of recovering her authority; but her army was overthrown at

Langside by the Regent, and she had then no resource but to pass into

England, and ask refuge with Queen Elizabeth. By her she was received with

a show of civility, but was in reality treated as a prisoner, and even

subjected to the indignity of a kind of trial, where her brother Moray

acted as her accuser. The proofs brought forward for her guilt were such

as not to allow of any judgment being passed against her by Elizabeth, and

it cannot be said that they have secured a decidedly unfavourable verdict

from posterity. The series of circumstances is, no doubt, calculated to

excite suspicion; yet they are not incompatible with the theory, that she

was trained into them by others; and it must be admitted that one who had

previously lived so blamelessly—rejecting the suit of Bothwell when they

were both free persons— and who afterwards made so noble an appearance

when adjudged to a cruel death for offences of which she was innocent, was

not the kind of person likely to have assisted in murdering a husband, or

to have deliberately united herself to one whom she believed to be his

murderer.

Under a protestant Regent, with the

friendship and aid of Elizabeth, whose interest it was to keep popery out

of the whole island, Scotland might have enjoyed some years of

tranquillity. Moray, whatever opinion may be entertained of his conduct

towards his sister, proved a vigorous and just ruler, insomuch as to gain

the title of the Good Regent; but he was early cut off in his

course, victim to private revenge at Linlithgow (January 23, 1569-70).

1567, Oct

The long-enduring system of predatory warfare carried on by the borderers

against England rendered them a lawless set at all times; but in the

present state of the government, they were unusually troublesome. ‘In all

this time,’ says the Diurnal of Occurrents, 'frae the queen's

grace’ putting in captivity to this time, the

thieves of Liddesdale made great hership on

the poor labourers of the ground, and that through wanting of justice; for

the realm was sae divided in sundry factions and conspirations, that there

was nae authority obeyed, nor nae justice execute.’ D.O.Sir

Richard Maitland of Lethington

gives us a lively description of these men and their practices:

‘Of Liddesdale the common thieves

Sae pertly steals now and reaves,

That nane may keep

Horse, nolt, or sheep,

For their mischieves.

They plainly through the country

rides,

I trow the meikle De’il them guids,

Where they onset,

Ay in their gait,

There is nae yett,

Nor door, them bides.

Thae thieves that steals and turses

hame

Ilk ane of them has ane to-name,

Will of the Laws,

Hab of the Shaws;

To tmak bare wa’s,

They think nae shame.

They spulyie puir men of their packs,

They leave them nought on bed nor balks,

Baith hen and cock,

With reel and rock,

The Laird’s Jock

All with

him taks.

They leave not spendle, spoon, nor

spit,

Bed, bolster, blanket, sark, nor

sheet;

John of the Park

Hypes kist and ark;

For all sic wark

He is right meet.

He is

weel-kenned,

Jock of

the Syde,

A greater thief did never

ride.

He never tires

For to break byres;

O’er muir and mires,

O’er guid ane guide....

Of stouth though now they

come good speed,

That nother of God nor men has dread,

Yet or I die,

Some shall them see

Hing on a tree,

While they be dead.’

[f it was at this time, as is

likely, that Sir Richard wrote these verses, he might well calculate on

the vigour of the Regent while

prophesying sad days for the

Border men.

'.....there was ane proclamation

[October 10], to meet the Regent in Peebles upon the 8 of November next,

for the repressing of the thieves in Annandale and Eskdale; but my Lord

Regent thinking they wald get advertisement, he prevented the day, and

came over the water secretly, and lodged in Dalkeith; this upon the 19 day

[October]; and upon the morrow he departed towards Hawick, where he came

both secretly and suddenly, and there took thirty-four thieves, whom he

partly caused hang and partly drown; five he let free upon caution; and

upon the 2nd day of November, he brought other ten with him to Edinburgh,

and there put them in irons.’---Bir.

We have some trace of these men in

the Lord Treasurer’s accounts as inmates of the Tolbooth of Edinburgh. On

the 30th of November, thirty-two pounds are paid to Andro Lindsay, keeper

of that prison, for the furnishing of meat and drink to Robert Elliot,

alias Clement’s Hob, and Archy Elliot, called Archy

Kene.

On the same day, twenty-three pounds four shillings are

disbursed for a month’s board in the same black hotel, for ‘Robert Elliot,

called Mirk Hob; Gavin Elliot, called Gawin of Ramsiegill;

Martin Elliot, called Martin of Heuchous; Robert Elliot, son to

Elder Will; Robert Elliot, called the Vicar’s Rob; Robert

Elliot, called Hob of Thorlieshope; Dandy Grosar, called

Richardtoncleucht; and Robert Grosar, called

Son to Cockston.’

In an act of the Privy Council, 6th

November 1567, it is alleged that the thieves of Liddesdale, and other

parts of the Scottish Border, have been in the habit, for some time past,

of taking sundry persons prisoners, and giving them up upon ransom—

exactly the conduct of the present banditti of the Apennines. It is also

averred that many persons are content to pay ‘black-mail’ to these

thieves, and sit under their protection, ‘permittand them to reif, herry,

and oppress their neighbours in their sicht, without contradiction or

stop.’ Such practices were now forbidden under severe penalties; and it

was enjoined that ‘when ony companies of thieves or broken men comes ower

the swires within the in-country,’ all dwelling in the bounds shall

‘incontinent cry on hie, raise the fray, and follow them, as weel in their

in-passing as out-passing,’ in order to recover the property which may

have been stolen.

Walter Scott of Harden, a famous

Border chief, was this year married to Mary Scott of Dryhope, commonly

called the Flower of Yarrow. The pair had six sons, from five of

whom descended the families of Harden (which became extinct); Highchesters,

now represented by Lord Polwarth, Raeburn (from which came Sir Walter

Scott of Abbotsford), Wool, and Synton; and six daughters, all of whom

were married to gentlemen of figure, and all had issue.

It is a curious consideration to the

many descendants of Walter Scott of Harden, that his marriage-contract is

signed by a notary, because none of the parties could write their names.

The father-in-law, Scott of Dryhope, bound himself to find Harden in horse

meat and man’s meat, at his own house, for a year and day; and five barons

engaged that he should remove at the expiration of that period, without

attempting to continue in possession by force.

Harden was a man of parts and

sagacity, and living to about the year 1629, was popularly remembered for

many a day thereafter under the name of ‘Auld Watt.’ One of his

descendants relates the following anecdote of him :—‘His sixth son was

slain at a fray, in a bunting-match, by Scott of Gilmanscleuch. His

brothers flew to arms; but the old laird secured them in the dungeon of

his tower, hurried to Edinburgh, stated the crime, and obtained a gift of

the lands of the offenders from the crown. He returned to Harden with

equal speed, released his sons, and shewed them the charter. "To horse,

lads!" cried the savage warrior, "and let us take possession! The lands of

Gilmanscleuch are well worth a dead son."'

Oct30

Bessie Tailefeir, in the Canongate, Edinburgh, having slandered Bailie

Thomas Hunter by saying ‘he had in his house ane false stoup [measure],’

which was found not to be true, she was sentenced to be brankit and

set on the Cross for an hour.

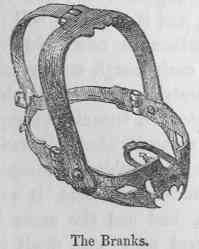

The punishment of branking, which was a customary

one for scolds, slanderers, and other offenders of a secondary class,

consisted in having the head enclosed in an iron frame, from which

projected a kind of spike, so as to enter the mouth and prevent speech.

Nov 20

Charles Sandeman, cook, on being made a member of the guild of Edinburgh,

came under an obligation that, from that time forth, ‘he sall not be seen

upon the causey,’ like other cooks, carrying meat to sell in common

houses, but cause his servants pass with the same; and ‘he sall hald his

tavern on the Hie Gait . . . . and behave himself honestly in all time

coming, under pain of escheat of his wines.’—E.

C. R.

Nov 24

‘. . . At 2 afternoon, the Laird of Airth and the Laird of Wemyss met upon

the Hie Gait of Edinburgh; and they and their followers faught a very

bluidy skirmish, where there was many hurt on both sides with shot of

pistol.’—Bir. Apparently in consequence of this affair, there was,

on the 27th, ‘a strait proclamation,’ discharging the wearing of

culverins, dags, pistolets, or ‘sic other firewerks,’ with injunctions

that any one contravening should be seized and subjected to summary trial,

‘as gif they had committit recent slauchters.’—P.

C. R.

This is the first of a series of

street-fights by which the Hie Gait of Edinburgh was reddened during the

reign of James VI, and which scarcely came to an end till his English

reign was far advanced. It is worthy of note that sword and buckler

were at this time the ordinary gear of gallant men in England—a

comparatively harmless furnishing; but we see that small firearms were

used in Scotland.

Dec 15

An act of parliament was passed to prevent horses being exported, being

found that so many had lately been taken to Bordeaux and other places

abroad, as to cause ‘great skaith’ by the raising of prices at home.

There has been a feeling of rivalry

between Perth and Dundee from time immemorial, and it probably will never

cease while both towns exist. At a parliament now held by the Regent

Moray, the representatives of each burgh strove for the next place after

Edinburgh in that equestrian procession which used to be called the

Riding of the Estates. A tumult consequently arose upon the street,

and it was with difficulty that this was stilled. Birrel relates how the

Regent was ‘much troubled to compose those two turbulent towns of Perth

and Dundee; and that ‘it was like to make a very great deal of business,

had not the same been mediate for the present by some discreet men who

dealt in the matter.’ Due investigation was afterwards made (January 9,

1567—8), that it might be ascertained ‘in whais default the said tumult

happenit.’ It was found that ‘James Wedderburn and George Mitchell,

burgesses of Dundee, and William Rysie, bearer of the handsenyie [ensign]

thereof,’ were no wise culpable; and they were accordingly allowed to

depart.

Dec 27

Alexander Blair younger of Balthayock, and George Drummond of Blair, gave

surety before the Privy Council for Alexander Blair of Freirton, near

Perth, ‘that Jonet Kincraigie, spouse to the said Alexander, sall be

harmless and skaithless of him and all that he may let, in time coming,

under the pain of five hundred merks; and als that he sail resave the said

Jonet in house, and treat, sustene, and entertene her honestly as becomes

ane honest man to do to his wife, in time coming;’ besides paying to her

children by a former husband their ‘bairn’s part of geir.’—P. C. R.

Dec 31

‘Robert Jack, merchant and burgess of Dundee, was

hangit and quarterit for false coin called Hardheads, whilk he had

brought out of Flanders.’—Bir. ‘Fals lyons callit hardheades,

plakis, balbeis, and other fals money,’ is the description given in

another record, literatim.

The hardhead was originally a French

coin, denominated in Guienne hardie, and identical with the liard.

It was of debased copper, and usually of the value of three-halfpence

Scotch; but further debasement was oftener than once resorted to by

Scottish rulers as a means of raising a little revenue. Knox, in 1559,

complains that ‘daily there were such numbers of lions (alias

called hardheads) prented, that the baseness thereof made all tbings

exceeding dear.’ So also the Regent Morton increased his unpopularity by

diminishing the value of hardheads from three half-pence to a penny, and

the plack-piece from fourpence to twopence.’

Robert Jack had probably made a sort

of mercantile speculation in bringing in a debased foreign hardhead.

The importance attached to his crime is indicated by the payment

(January 28, 1567—8) of £33, 6s. 3d. to George Monro of Dalcartie, for

‘expenses made by him upon six horsemen and four footmen for the sure

convoying of Robert Jack, being apprehended in Ross for false cunyie.’

1568, Jan 5

It may somewhat modify the views generally taken of the destruction of

relics of the ancient religion under the Protestant governments succeeding

the Reformation, that John Lockhart of Bar was denounced rebel at this

time for conveying John Macbrair forth of the castle of Hamilton, and ‘for

down-casting of images in the kirk of Ayr and other places.’

About the same time, the Regent

learned that the lead upon the cathedrals of Aberdeen and Elgin was in the

course of being piecemeal taken away. Thinking it as well that some public

good should be obtained from this material, the Privy Council ordered

(February 7, 1567—8) that the whole be taken down and sold for the support

of the army now required to reduce the king’s rebels to obedience.

Jan 17

‘A play made by Robert Semple,’ was ‘played before the Lord Regent and

diverse others of the nobility.’—Bir. There have been several

conjectures as to this play and its author, with little satisfactory

result. It was probably a very simple representation of some historical

scene or transaction, such as we can imagine the life of the execrable

Bothwell to have gratefully furnished before such a company. Semple

appears to have been in such a rank of life as not to be above ordinary

pecuniary rewards for his services, as on the 12th of February there is an

entry in the treasurer’s books of £66, 18s. 4d. ‘to Robert Semple.’ He was

a fruitful, but dull writer, being the author of The Regentis Trajedie,

1570; The Bishopis Lyfe and Testament, 1571; My

Lord Methvenis Trajedie,

1572; and ,The Siege of the Castle of Edinburgh,

1573: besides various poems preserved in the Bannatyne Manuscript.

Feb 24

Seeing that ‘in the spring of the year all kinds of flesh decays and grows

out of season, and that it is convenient for the commonweal that they be

sparit during that time, to the end that they may be mair plenteous and

better cheap the rest of the year,’ the Privy Council forbade the use of

flesh of any kind during ‘Lentern.’ Fleshers, hostelers, cooks, and

taverners, were forbidden to slay any animals for use during that season

hereafter, under pain of confiscation of their movable goods.—P.

C. R. This order was kept up in the same terms for many years, a

forced economy preserving a rule formerly based on a religious principle.

Mar 4

The Regent granted a licence to Cornelius De Vois, a Dutchman, for

nineteen years, to search for gold and silver in any part of Scotland,

‘break the ground, mak sinks and pots therein, and to put labourers

thereto,’ as he might think expedient, with assurance of full protection

from the government, paying in requital for every hundred ounces of gold

or silver which could be purified by washing, eight ounces, and for every

hundred of the same which required the more expensive process of a

purification by fire, four ounces—P.

C. R.

Stephen Atkinson, who speculated in

the gold-mines of Scotland a generation later, gives us some account of

Cornelius De Vois, whom he calls a German lapidary, and who, he says, had

come to Scotland with recommendations from Queen Elizabeth. According to

this somewhat foolish writer, ‘Cornelius went to view the said mountains

in Clydesdale and Nydesdale, upon which mountains he got a small taste of

small gold. This was a whetstone to sharpen his knife upon; and this

natural gold tasted so sweet as the honeycomb in his mouth. And then he

consulted with his friends at Edinburgh, and by his persuasions provoked

them to adventure with him, shewing them at first the natural gold, which

he called the temptable gold, or alluring gold. It was in sterns, and some

like unto birds’ eyes and eggs: he compared it unto a woman’s eye, which

entiseth her lover into her bosom.’ Cornelius was not inferior to his

class in speculative extravagance. He found in his golden dreams a

solution for the question regarding the poor. He saw Scotland aud England

‘both oppressed with poor people which beg from door to door for want of

employment, and no man looketh to it.’ But all these people were to find

good and profitable employment if his projects were adopted. We are not

accustomed to consider our countrymen inferior in energy and enterprise to

the Germans. Yet Cornelius stated, that if he had been able to shew in his

own country such indications of mineral wealth as he had found in

Scotland, ‘then the whole country would confederate, and not rest till

young and old that were able be set to work thereat, and to discover this

treasure-house from whence this gold descended; and the people, from ten

years old till ten times ten years old, should work thereat: no charges

whatsoever should be spared, till mountains and mosses were turned into

valleys and dales, but this treasure-house should be discovered.’

It appears that Cornelius so far

prevailed on the Scots to ‘confederate,’ that they raised a stock of £5000

Scots, equal to about £416 sterling, and worked the mines under royal

privileges. According to Atkinson, this adventurer ‘had sixscore men at

work in valleys and dales. He employed both lads and lasses, idle men and

women, which before went a-begging. He profited by their work, and they

lived well and contented.’ They sought for the valuable metal by washing

the detritus in the bottoms of the valleys, receiving from their employer

a mark sterling for every ounce they realised. So long after as 1619, one

John Gibson survived in the village of Crawford to relate how he had

gathered gold in these valleys in pieces ‘like birds’ eyes and birds’

eggs,’ the best being found, he said, in Glengaber Water, in Ettrick,

which he sold for 6s. 8d. sterling per ounce to the Earl of Morton.

Cornelius, within the space of thirty days, sent to the cunyie-house in

Edinburgh as much as eight pound-weight of gold, a quantity which would

now bring £450 sterling.

What ultimately came of Cornelius’s

adventure does not appear. He vanishes notelessly from the field. We are

told by Atkinson that the adventure was subsequently taken up by one

Abraham Grey, a Dutchman heretofore resident in England, commonly called

Greybeard, from his having a beard which reached to his girdle. He

hired country-people at 4d. a day, to wash the detritus of the valleys

around Wanlock-head for gold; and it is added, that enough was found to

make ‘a very fair deep basin of natural gold,’ which was presented by the

Regent Morton to the French king, filled with gold pieces, also the

production of Scotland.

The same valleys were afterwards

searched for gold by an Englishman named George Bowes, who also sunk

shafts in the rock, but probably with limited success, as has hitherto

been experienced in ninety-nine out of every hundred instances, according

to Sir Roderick Murchison.

In consequence of an extremely dry

summer, the yield of grain and herbage in 1567 was exceedingly defective.

The ensuing winter being unusually severe, there was a sad failure of the

means of supporting the domestic animals. A stone of hay came to be sold

in Derbyshire at fivepence, which seems to have been regarded as a

starvation price. There was a general mortality among the sheep and

horses. In Scotland, the opening of 1568 was marked by scarcity and all

its attendant evils. ‘There was,’ says a contemporary chronicler,

‘exceeding dearth of corns, in respect of the penury thereof in the land,

and that beforehand a great quantity thereof was transported to other

kingdoms: for remeed whereof inhibitions were made sae far out of season,

that nae victual should be transported farth of the country under the pain

of confiscation, even then when there was no more left either to satisfy

the indigent people, or to plenish the ordinar mercats of the country as

appertenit.’ - H. K. J.

During his short administration, the

Regent Moray gave a large portion of his time and attention to the

repression of lawless people. Justice was executed in no sparing manner.

March 8, 1567—8, ‘the Regent went to Glasgow, and there held ane

justiceaire, where there was execute about the number of twenty-eight

persons for divers crimes.’ July 1568, he ‘rade to St Andrews, and

causit drown a man cailit Alexander Macker and six more, for piracy.’ Sep.

13, ‘the Lord Regent rade to the fair to Jedburgh, to apprehend the

thieves; but they being advertised of his coming, came not to the fair;

sae he was frustrate of his intention, excepting three thieves whilk he

took, and caused hang within the town there.’—Bir. April 1569, the

Regent made a raid to the Border against the thieves, accompanied by a

party of English. ‘But the thieves keepit themselves in sic manner, that

the Regent gat nane thereof, nor did little other thing, except he brint

and reft the places of Mangerton and Whithope, with divers other houses

belonging to the said thieves.’—D. O.

In the same month, a number of the

most considerable persons in the southern counties entered into a bond at

Kelso, agreeing to be obedient subjects to the Regent Earl of Moray, and

to do all in their power for the putting down of the thieves of Liddesdale,

Ewesdale, Eskdale, and Annandale, especially those of the names Armstrong,

Elliot, Nickson, Croser [Grozart?], Little, Bateson, Thomson, Irving,

Bell, Johnston, Glendorting, Routledge, Henderson, and Scott; not

resetting or intercommuning with them, their wives, bairns, tenants, and

servants, or suffering any meat or drink to be carried to them, ‘where we

may let;’ also, if, ‘in case of the resistance or pursuit of any of the

said thieves, it sail happen to ony of them to be slain or brint, or ony

of us and our friends to be harmit by them, we sall ever esteem the

quarrel and deadly feid equal to us all, and sall never agree with the

said thieves but together, with ane consent and advice.’

1568, July 13

Axel Wiffirt, servant of the king of Denmark, was licensed to levy 2000

men of war in Scotland, and to convey them away armed as culviriners on

foot, ‘as they best can provide them,’ being to serve the Danish monarch

in his wars.

July 15

‘Touran Murray, brother-german to the Laird of Tullibardine, was shot and

slain out of the place of Anchtertyre, in Stratherne, by one Wood [Mad]

Andrew Murray and his confederates, who kept the said place certain days,

and slew some six persons more, yet made escape at that present.’—Bir.

Sep 8

‘Ane called James Dalgliesh, merchant, brought the pest in [to]

Edinburgh.’—D. 0.

According to custom in Edinburgh,

when this dire visitor made his appearance, the families which proved to

be infected were compelled to remove, with all their goods and furniture,

out to the Burgh-moor, where they lodged in wretched huts hastily erected

for their accommodation. They were allowed to be visited by their friends,

in company with an officer, after eleven in the forenoon; any one going

earlier was liable to be punished with death—as were those who concealed

the pest in their houses. Their clothes were meanwhile purified by boiling

in a large caldron erected in the open air, and their houses were

‘clengit’ by the proper officers. All these regulations were under the

care of two citizens selected for the purpose, arid called Bailies of

the Muir; for each of whom, as for the cleansers and bearers of the

dead, a gown of gray was made, with a white St Andrew’s cross before and

behind, to distinguish them from other people. Another arrangement of the

day was, ‘that there be made twa close biers, with four feet, coloured

over with black, and [ane] white cross with ane bell to be hung upon the

side of the said bier, whilk sall mak warning to the people.’’

The public policy was directed

rather to the preservation of the untainted, than to the recovery of the

sick. In other words, selfishness ruled the day. The inhumanity towards

the humbler classes was dreadful. Well might Maister Gilbert Skeyne,

Doctour in Medicine, remark in his little tract on the pest, now

printed in Edinburgh: ‘Every ane is become sae detestable to other (whilk

is to be lamentit), and specially the puir in the sight of the rich, as

gif they were not equal with them touching their creation, but rather

without saul or spirit, as beasts degenerate fra mankind.’ This

worthy mediciner tells us, indeed, that he was partly moved to publish his

book by ‘seeand the puir in Christ inlaik [perish] without assistance of

support in body, all men detestand aspection, speech, or communication

with them.’

Dr Skeyne’s treatise, which consists

of only forty-six very small pages, gives us an idea of the views of the

learned of those days regarding the pest. He describes it as ‘ane

feverable infection, maist cruel, and sundry ways strikand down mony in

haste.’ It proceeds, in his opinion, from a corruption of the air, ‘whilk

has strength and wickedness above all natural putrefaction,’ and which he

traces immediately to the wrath of the just God at the sins of mankind.

There are, however, inferior causes, as stagnant waters, corrupting animal

matters and filth, the eating of unwholesome meat and decaying fruits, and

the drinking of corrupt water. Extraordinary humidity in the atmophere is

also dwelt upon as a powerful cause, especially when it follows in autumn

after a hot summer. ‘Great dearth of victual, whereby men are constrained

to eat evil and corrupt meats,’ he sets down as a cause much less notable.

He does not forget to advert to the suspicious inter-meddling of comets

and shooting-stars. ‘Nae pest,’ he says, ‘continually endures mair than

three years;’ and he remarks how ‘we daily see the puir mair subject to

sic calamity nor the potent.’

Dr Skeyne’s regimen for the pest

regards both its prevention and its cure, and involves an immense variety

of curious recipes and rules of treatment, expressed partly in Latin and

partly in English. He ends by calling his readers to observe—’As there is

diversity of time, country, age, and consuetude to be observit in time of

ministration of ony medicine preservative or curative, even sae there is

divers kinds of pest, whilk may be easily knawn and divided by

weel-learnit physicians, whase counsel in time of sic danger of life is

baith profitable and necessar, in respect that in this pestilential

disease every ane is mair blind nor the moudiewort in sic things as

concerns their awn health.’

There has been preserved a curious

letter which Adam Bothwell, bishop of Orkney, addressed in this time of

plague to his brother-in-law, Sir Archibald Napier of Merchiston,

regarding the dangers in which the latter was placed by the nearness of

his house to the bivouac of the infected on the Burgh-moor.’ It opens with

an allusion to Sir Archibald’s present position as a friend of Queen Mary

in trouble with the Regent:

‘RICHT HONOURABLE SIR AND BROTHER—I

heard, the day, the rigorous answer and refuse that ye gat, whereof I was

not weel apayit. But always I pray you, as ye are set amids twa great

inconvenients, travel to eschew them baith. The ane is maist evident—to

wit, the remaining in your awn place where ye are; for by the number of

sick folk that gaes out of the town, the muir is [li]able to be

overspread; and it cannot be but, through the nearness of your place and

the indigence of them that are put out, they sall continually repair about

your room, and through their conversation infect some of your servants,

whereby they sall precipitate yourself and your children in maist extreme

danger. And as I see ye have foreseen the same for the young folk, whaise

bluid is in maist peril to be infectit first, and therefore purposes to

send them away to Menteith, where I wald wiss at God that ye war yourself,

without offence of authority, or of your band, sae that your house get nae

skaith. But yet, sir, there is ane mid way whilk ye suld not omit, whilk

is to withdraw you frae that side of the town to some house upon the north

side of the samen; whereof ye may have in borrowing, when ye sall have to

do—to wit, the Gray Crook, Innerleith’s self, Wairdie, or sic other places

as ye could choose within ane mile; whereinto I wald suppose ye wald be in

less danger than in Merchanston. And close up your houses, your granges,

your barns, and all, and suffer nae man come therein, while [till] it

please God to put ane stay to this great plague; and in the meantime, make

you to live upon your penny, or on sic thing as comes to yon out of Lennox

or Menteith whilk gif ye do not, I see ye will ruin yourself; and howbeit

I escape in this voyage, I will never look to see you again, whilk were

some mair regret to me than I will expreme by writing. Always [I] beseeks

you, as ye love your awn weal, the weal of your house, and us your friends

that wald you weel, to tak sure order in this behalf; and, howbeit your

evil favourers wald cast you away, yet ye tak better keep on yourself, and

mak not them to rejoice, and us your friends to mourn baith at ance. Whilk

God forbid, and for his goodness, preserve you and your posterity from sic

skaith, and maintein you in [his] holy keeping for ever. Of Edinburgh, the

21st day of September 1568, by your brother at power,

‘THE BISHOP OF ORKNEY.’

The bishop speaks with unmistakable

friendship for his brother-in-law; but what he says and what he does not

say of the miserables of the Burgh-moor, tends much to confirm Dr Skeyne’s

remarks on the absence of Christian kindness among the upper classes

towards the afflicted poor on this occasion.

This pestilence, lasting till

February, is said to have carried off 2500 persons in Edinburgh, which

could not be much less than a tenth of the population. From the double

cause of the pest and the absence of the Regent in England, there were

‘nae diets of Justiciary halden frae the hinderend of August to the second

day of March.' Such of the inhabitants of the Canongate as were affected

had to go out and live in huts on the Hill (by which is probably meant

Salisbury Crags), and there stay till they were ‘clengit.’ A collection of

money was made among the other inhabitants for their support.

The distresses of pestilence were

preceded and attended by those of a famine, which suffered a great and

sudden abatement in the month of August 1569, perhaps in consequence of

favourable appearances in the crop then about to be gathered. At least, we

are informed by the Diurnal of Occurrent:, that on that day, in the

forenoon, ‘the boll of ait meal was sauld for 3l. 12s., the boll of

wheat for 41. 10s., and the boll of beare for 3l.; but ere

twa afternoon upon the same day, the boll of ait meal was sauld for 40s.,

38s., and 36s., the boll of wheat for 50s., and the beare for 33s.'-

D.D.

Little doubt is now entertained that

the exanthematous disease called long ago the Pest, and now the Plague,

and which has happily been unknown in the British Islands for two

centuries, was the consequence of miasma arising from crowded and filthy

living, acting on bodies predisposed by deficient aliment and other

causes, and that at a certain stage it assumed a contagious character. It

will be found throughout the present work that the malady generally,

though not invariably, followed dearth and famine—a generalisation

harmonising with the observations of Professor Alison as to the connection

between destitution and typhus fever, and supporting the views of those

who hold that it is for the interest of the community that all its members

have a sufficiency of the necessaries of life. The pest was not the only

epidemic which afflicted our ancestors in consequence of erroneous living

and misery endured by great multitudes of people. There was one called the

land-ill or wanie-ill, which seems to have been of the

nature of cholera. In an early chronicle quoted below, is the following

striking notice of this kind of malady in connection with famine as

occurring in 1439 :—‘The samen time there was in Scotland a great dearth,

for the boll of wheat was at 40s., and the boll of ait meal 30s.; and

verily the dearth was sae great that there died a passing [number of]

people for hunger. And als the land-ill, the wame-ill, was so violent,

that there died mae that year than ever there died, owther in pestilence,

or yet in ony other sickness in Scotland. And that samen year the

pestilence came in Scotland, and began at Dumfries, and it was callit the

Pestilence but Mercy, for there took it nane that ever recoverit,

but they died within twenty-four hours.’

Oct

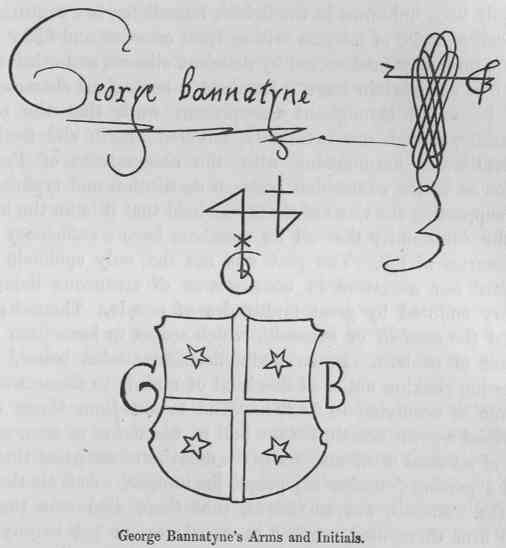

At the time when the pest broke out in Edinburgh, there lived in the city

a young man of the middle class, bearing the name of George Bannatyne, who

was somewhat addicted to the vain and unprofitable art of poesy. He was

acquainted with the writings of his predecessors, Dunbar, Douglas,

Henryson, Montgomery, Scott, and others, through the manuscripts to which

alone they had as yet been committed. it was not then the custom to print

literary productions unless for some reason external to their literary

character, and these poems, therefore, were existing in the same peril of

not being preserved to posterity as the works of Ennius in the days of

Augustus. In all probability, the greater part of them, if not nearly the

whole, would have been lost, but for an accidental circumstance connected

with the plague now raging.

In that terrible time, when hundreds

were dying in the city, and apprehensions for their own safety engrossed

every mind, the young man George Bannatyne passed into retirement, and for

three months devoted himself to the task of transcribing the fugitive

productions of the Scottish muse into a fair volume. His retreat is

supposed to have been the old manor-house of Newtyie, near the village of

Meigle in Strathmore, and nothing could be more likely, as this was the

country-house of his father, who seems to have been a prosperous lawyer in

Edinburgh. In the short space of time mentioned, George had copied in a

good hand, from the mutilated and obscure manuscripts he possessed, three

hundred and seventy-two poems, covering no less than eight hundred folio

pages; a labour by which he has secured the eternal gratitude of his

countrymen, and established for himself a fame granted to but few for

their own compositions. The volume - celebrated as the BANNATYNE

MANUSCRIPT - still exists, under the greatest veneration, in the

Advocates’ Library, Edinburgh, after yielding from its ample stores the

materials of Ramsay’s, Hailes’s, and other printed selections.’

Nov 18

In this time of dearth and pestilence, the council of the Canongate

providently ordained that ‘the fourpenny loaf be weel baken and dried,

gude and sufficient stuff, and keep the measures and paik of

twenty-two ounces;’ ‘that nae browsters nor ony tapsters sell ony dearer

ale nor 6d. the pint;’ and ‘that nae venters of wine buy nae new wine

dearer than that they may sell the same commonly to all our sovereign’s

lieges for 16d. the pint.’

They also ordained (January 10,

1568—9), that ‘nae manner of person inhabiter within this burgh, venters

of wine, hosters, or tapsters of ale, nor others whatsomever, thole or

permit ony maner of persons to drink, keep company at table in common

taverners’ houses, upon Sunday, the time of preaching, under the pain of

forty shillings, to be upta’en of the man and wife wha aucht the said

taverners’ houses sae oft as they fails, but favour.’

It is evident from this injunction,

that the keeping of public-houses open on Sundays, at times different from

those during which there was public worship, was not then forbidden.

1569. Jan 10

In presence of the magistrates of the Canongate, Edinburgh, ‘William

Heriot, younger, baxter, became, out of his awn free motive will,

cautioner for George Heriot, that the said George sall remove furth of

this burgh and freedom thereof, within the space of fifteen days next, and

nae be fund thereintill, in case the said George associate not himself to

the religion of Christ’s kirk, and satisfie the kirk in making of

repentance, as effeirs.’—C. C. R

This was a part of the process of

completing the Reformation.

May

'...the Regent made progress first to Stirling, where four priests of

Dumblane were condemnit to the death, for saying of mess against the act

of parliament; but he remittit their lives, and causit them to be bund to

the mercat cross with their vestments and chalices in derision, where the

people cast eggs and other villanie at their faces, by the space of ane

hour; and thereafter their vestments and chalices were burnt to ashes.

From that he passed to Sanctandrois, where a notable sorcerer called Nic

Neville was condemnit to the death and brunt; and a Frenchman callit

Paris, wha was ane of the devisers of the king’s death, was hangit in

Sanctandrois, and with him William Stewart, Lyon King of Arms, for divers

points of witchcraft and necromancy.’—H.

K. J.

Aug 16

The Diurnal of Occurrents relates the Regent’s proceedings against

the powers of the other world in this journey in a style equally cool and

laconic. ‘In my Lord Regent’s passing to the north, he causit burn certain

witches in Sanctandrois, and in returning he causit burn ane other company

of witches in Dundee.’

Sep

The Regent once more set out on an expedition against the Border thieves,

attended by a hundred men of war. In the words of a poetical panegyrist

'...having established all thing in

this sort,

To Liddesdale again he did resort.

Through Ewesdale, Esdale, and all the dales rade he,

And also lay three nichts in Cannobie,

Where nae prince lay thir hunder years before;

Nae thief durst stir, they did him fear so sore;

And that they should nae mair their theft allege,

Threescore and twelve he brought of them in pledge,

Syne warded them, whilk made the rest keep order,

Than might the rash buss keep lye on

the Border."

It is said that no former ruler had

ever so thoroughly awed the Border men. On his return to Edinburgh in

November, he distributed the hostages among certain barons of the realm.

This, however, was the last of

Moray’s expeditions against the thieves. He was approaching the end of his

career, doomed by party hatred in conjunction with private malice.

1570, Jan 23

‘The Earl of Moray, the Good Regent, was slain in Linlithgow by James

Hamilton of Bothwell-haugh, who shot the said Regent with a gun out at ane

window, and presently thereafter fled out at the back, and leapt on a very

good horse, which the Hamiltons had ready waiting for him; and, being

followed speedily, after that spur and wand had failed him, he drew forth

his dagger, and struck his horse behind; whilk causit the horse to leap a

very broad stank; by whilk means he escaped.’—Bir. |