|

THE regent, Mary de Guise, having

died in June 1560, while her daughter Mary, the nominally reigning queen,

was still in France, the management of affairs fell into the hands of the

body of nobles, styled Lords of the Congregation, who had struggled for

the establishment of the Protestant faith. The chief of these was Lord

James Stuart, an illegitimate son of James V., and brother of the

queen—the man of by far the greatest sagacity and energy of his age and

country, and a most earnest votary of the new religion.

Becoming a widow in December 1560,

by the death of her husband, Francis II., Mary no longer had any tie

binding her to France, and consequently she resolved on returning to her

own dominions. When she arrived in Edinburgh, in August 1561, she found

the Protestant religion so firmly established, and so universally accepted

by the people—there being only some secluded districts where Catholicism

still prevailed—that, so far from having a chance of restoring her kingdom

to Rome, as she, ‘an unpersuaded princess,’ might have wished to do, it

was with the greatest difficulty that she could be allowed to have the

mass performed in a private room in her palace. The people regarded her

beautiful face with affection; and, as she allowed her brother, Lord

James, and other Protestant nobles to act for her, her government was far

from unpopular.

Mary’s conduct towards the

Protestant cause appeared as that of one who submits to what cannot be

resisted. Before she had been fifteen months in the country, she

accompanied her brother (whom she created Earl of Moray) on an expedition

to the north, where she broke the power of the Gordon family, who boasted

they could restore the Catholic faith in three counties. What is still

more remarkable, she dealt with the patrimony of the church, accepting

part of the spoils for the use of the state. It is believed, nevertheless,

that she designed ultimately to act in concert with the Catholic powers of

the continent for the restoration of the old religion in Scotland. One

obvious motive for keeping on fair terms with Protestantism for the

present, lay in her hopes of succeeding to the English crown, in the event

of the death of Elizabeth, whose next heir she was.

1561

A custom, dating far back in

Catholic times, prevailed in Edinburgh in unchecked luxuriance down almost

to the time of the Reformation. It consisted in a set of unruly dramatic

games, called Robin Hood,

the Abbot of Unreason, and the Queen of May,

which were enacted every year in the floral month just mentioned. The

interest felt by the populace in these whimsical merry-makings was

intense: At the approach of May, they assembled and chose some respectable

individuals of their number, very grave and reverend citizens perhaps, to

act the parts of Robin Hood and Little John, of the Lord of Inobedience,

or the Abbot of Unreason, and ‘make sports and jocosities’ for them. If

the chosen actors felt it inconsistent with their tastes, gravity, or

engagements, to don a fantastic dress, caper and dance, and incite their

neighbours to do the like, they could only be excused on paying a fine. On

the appointed day, always a Sunday or holiday, the people assembled in

their best attire and in military array, and marched in blithe procession

to some neighbouring field, where the fitting preparations had been made

for their amusement. Robin Hood and Little John robbed bishops, fought

with pinners, and contended in archery among themselves, as they had done

in reality two centuries before. The Abbot of Unreason kicked up his heels

and played antics like a modern pantaloon. The popular relish for all this

was such as can scarcely now be credited. ‘A learned prelate [Latimer]

preaching before Edward VI., observes, that he once came to a town upon a

holiday, and gave information on the evening before of his design to

preach. But next day when he came to the church, he found the door locked.

He tarried half an hour ere the key could be found, and instead of a

willing audience, some one told him: "This is a busy day with us; we

cannot hear you. It is Robin Hood’s day. The parish are gone abroad to

gather for Robin Hood. I pray you let [hinder] them not." I was fain (says

the bishop) to give place to Robin Hood. I thought my rochet should have

been regarded, though I were not; but it would not serve. It was fain to

give place to Robin Hood’s men.’

Such were the Robin Hood plays of

Catholic and unthinking times. By and by, when the Reformation approached,

they were found to be disorderly and discreditable, and an act of

parliament was passed against them. Still, while the upper and more

serious classes frowned, the common sort of people loved the sport too

much to resign it without a struggle. It came to be one of the first

difficulties of the men who had carried through the Reformation, how to

wrestle the people out of their love of the May-games.

In April 1561, one George Dune was

chosen in Edinburgh as Robin Hood and Lord of Inobedience, and on Sunday

the 12th of May, he and a great number of other persons came riotously

into the city, with an ensign and arms in their hands, in disregard of

both the act of parliament and an act of the town-council. Notwithstanding

an effort of the magistrates to turn them back, they passed to the Castle

Hill, and thence returned at their own pleasure. For this offence a

cordiner’s servant, named James Gillon, was condemned to be hanged on the

21st of July.

July 27‘

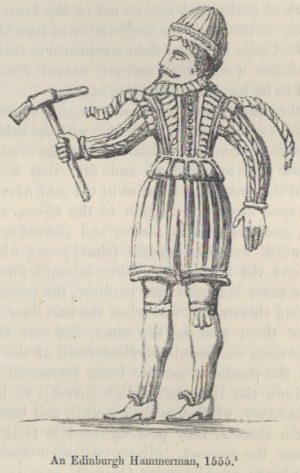

When the time of the poor man’s

hanging approachit, and that the [hangman] was coming to the gibbet with

the ladder, upon which the said cordiner should have been hangit, the

craftsmen’s childer’ and servants past to armour; and first they housit

Alexander Guthrie and the provost and bailies in the said Alexander’s

writing booth, and sync came down again to the Cross, and dang down the

gibbet, and brake it in pieces, and thereafter passed to the Tolbooth,

whilk was then steekit [shut]; and when they could not apprehend the keys

thereof, they brought fore-hammers and dang up the same Tolbooth door

perforce, the provost, bailies, and others looking thereupon; and when the

said door was broken up, ane part of them past in the same, and not

allenarly [only] brought the same condemnit cordiner forth of the said

Tolbooth, but also all the remanent persons being thereintill; and this

done they past down the Hie Gait [High Street], to have past forth at the

Nether Bow, whilk was then steekit, and because they could not get furth

thereat, they past up the Hie Gait again; and in the meantime the provost,

bailies, and their assisters being in the writing-booth of Alexander

Guthrie, past to the Tolbooth; and in their passing up the said gait, they

being in the Tolbooth, as said is, shot forth at the said servants ane dag,

and hurt ane servant of the craftemen’s. That being done, there was

naething but tak and slay; that is, the ane part shooting forth and

casting stanes, the other part shooting hagbuts in again; and sae the

craftsmen’s servants held them [conducted themselves] continually fra

three hours afternoon while [till] aucht at even, and never ane man of the

town steirit to defend their provost and bailies. And then they sent to

the masters of the craftsmen to cause them, gif they might, to stay the

said servants; wha purposed to stay the same, but they could not come to

pass, but the servants said they wald have ane revenge for the man whilk

was hurt. And thereafter the provost sent ane messenger to the constable

of the Castle to come to stay the matter, wha came; and he with the

masters of the craftsmen treated on this manner, that the provost and

bailies should discharge all manner of actions whilk they had against the

said craftschilder in ony time bygane, and charged all their masters to

receive them in service as they did of before, and promittit never to

pursue them in time to come for the same. And this being done and

proclaimit, they skaled [disbanded], and the provost and bailies came

furth of the Tolbooth.’—D. 0.

This was altogether an unprotestant

movement, though springing only from a thoughtless love of sport. We may

see in the attack on the Tolbooth a foreshadow of the doings of the

Porteous mob in a later age. It appears that the magistrates, though

reformers, were unpopular; hence the neutrality of the citizens, who, when

solicited to interfere for the defence of the city-rulers, went to their

four hours penny, and returned for answer: ‘They will be magistrates

alone; let them rule the multitude alone.’—Cal. Thirteen persons

were afterwards ‘fylit’ by an assize for refusing to help the

magistrates.—Pit.

On its being known that Queen Mary

was about to arrive in Scotland from France, there was a great flocking of

the upper class of people from all parts of the country to Edinburgh, ‘as

it were to a common spectacle.’

Aug 19

The queen arrived with her two

vessels in Leith Road, at seven in the morning of a dull autumn-day. She

was accompanied by her three uncles of the House of Guise—the Duc d’Aumale,

the Grand Prior, and the Marquis d’Elbeuf; besides Monsieur d’Amville, son

of the constable of France, her four gentlewomen, called the Maries,

and many persons of inferior note. To pursue the narrative of one who

looked on the scene with an evil eye: ‘The very face of heaven, the time

of her arrival, did manifestly speak what comfort was brought unto this

country with her; to wit, sorrow, dolour, darkness, and all impiety; for

in the memory of man, that day of the year, was never seen a more dolorous

face of the heaven, than was at her arrival, which two days after did so

continue; for beside the surface weet and corruption of the air, the mist

was so thick and so dark, that scarce might any man espy ane other the

length of twa butts. The sun was not seen to shine two days before nor two

days after. That forewarning gave God unto us; but, alas, the most part

were blind.

‘At the sound of the cannons which

the galleys shot, the multitude being advertised, happy was he and she

that first might have presence of the queen [At ten hours her hieness

landed upon the shore of Leith.] Because the palace of Holyroodhouse was

not thoroughly put in order . . . . she remained [in Andrew Lamb’s house]

in Leith till towards the evening, and then repaired thither. In the way

betwixt Leith and the Abbey, met her the rebels of the crafts . . . . that

had violated the authority of the magistrates and had besieged the

provost; but because she was sufficiently instructed that all they did was

done in despite of the religion, they were easily appardoned. Fires of joy

were set forth all night, and a company of the most honest, with

instruments of music, and with musicians, gave their salutations at her

chalmer window. The melody, as she alleged, liked her weel; and she willed

the same to be continued some nichts after.’ —Knox.

The magistrates of Edinburgh, although all of them

zealous for the reformed religion, resolved to give their young sovereign

a gallant reception, taxing the community for the expenses. It was

likewise thought good that, ‘for the honour and pleasure of our sovereign,

ane banquet sould be made upon Sunday next, to the princes, our said

sovereign’s kinsmen.’

Sep 2

The queen ‘made her entres in the burgh of Edinburgh in this manner. Her

hieness departed of Holyroodhouse, and rade by the Lang Gate [A road in

the line of Princess Street] on the north side

of

the burgh, unto the time she came to the Castle, where was ane yett [gate]

made to her, at the whilk she, accompanied by the maist part of the

nobility of Scotland, came in and rade up the castle-bank to the Castle,

and dined therein.

‘When she had dined at twelve hours,

her hieness came furth of the Castle

. . . . ,

at whilk departing the artillery shot vehemently. Thereafter, when she was

ridand down the Castle Hill, there met her hieness ane convoy of the young

men of the burgh, to the number of fifty or thereby, their bodies and

thies covered with yellow taffetas, their arms and legs frae the knee down

bare, coloured with black, in manner of Moors; upon their heads black

hats, and on their faces black visors; in their mouths rings garnished

with untellable precious stanes; about their necks, legs, and arms,

infinite of chains of gold: together with saxteen of the maist honest men

of the town, clad in velvet gowns and velvet bonnets, bearaud and gangand

about the pall under whilk her hieness rade; whilk pall was of fine

purpour velvet, lined with red taffetas, fringed with gold and silk. After

them was ane cart with certain bairns, together with ane coffer wherein

was the cupboard and propine [gift] whilk should be propiuit to her

hieness. When her grace came forward to the Butter Tron, the nobility and

convoy precedand, there was ane port made of timber in maist honourable

manner, coloured with fine colours, hung with sundry arms; upon whilk port

was singand certain bairns in the maist heavenly wise; under the whilk

port there was ane cloud opening with four leaves, in the whilk was put

ane bonnie bairn. When the queen’s hieness was coming through

the said port, the cloud openit, and the

bairn descended down as it had been ane angel, and deliverit to her

hieness the keys of the town, together with ane Bible and ane Psalm-buik

covent with fine purpour velvet.’ After the said bairn had spoken some

small speeches, he delivered also to her hieness three writings, the

tenour whereof is uncertain. That being done, the bairn ascended in the

cloud, and the said cloud steekit.

‘Thereafter the queen’s grace came

down to the Tolbooth, at the whilk was

. . . . twa seaffats, ane aboon, and ane under

that. Upon the under was situate ane fair virgin called Fortune, under the

whilk was three fair virgins, all clad in maist precious attirement,

called, Justice, and Policy. And

after ane little speech made there, the queen’s grace came to the Cross,

where there was standand four fair virgins, clad in the maist heavenly

claithing, and frae the whilk Cross the wine ran out at the spouts in

great abundance. There was the noise of people casting the glasses with

wine.

‘This being done, our lady came to

the Salt Tron, where there was some speakers; and after ane little speech,

they burnt upon the seaffat made at the said Tron the manner of ane

sacrifice. Sae that being done, she departed to the Nether Bow, where

there was ane other scaffat made, having ane dragon in the same, with some

speeches; and after the dragon was burnt, and the queen’s grace heard ane

psalm sung, her hieness passed to the abbey of Holyroodhouse, with the

said convoy and nobilities. There the bairns whilk was in the cart with

the propine made some speech concerning the putting away of the mass, and

thereafter sang ane psalm. And this being done, the

. . . .

honest men remained in her outer chalmer, and desired

her grace to receive the said cupboard, whilk was double over-gilt; the

price thereof was 2000 merks; wha received the same and thankit them

thereof. And sae the honest men and convoy come to Edinburgh.’—D. O.

The Sunday banquet to the queen’s

uncles duly took place in the cardinal’s lodging in Blackfriars’ Wynd. The

entire expenses on the occasion of this royal reception were 4000 merks

Before the queen had been settled

for many weeks in her capital, the new-born zeal of the people against the

old religion found vent in a way that shewed in how little danger she was

of being spoilt by complaisance on the part of her subjects. The provost

of Edinburgh, Archibald Douglas, with the bailies and council, eausit ane

proclamation to be proelaimit at the Cross of Edinburgh, commanding and

charging all and sundry monks, friars, priests, and all others papists and

profane persons, to pass furth of Edinburgh within twenty-four hours,

under the pain of burning of disobeyers upon the cheek and harling of them

through the town upon ane cart. At the whilk proclamation, the queen’s

grace was very commovit.’—D. O. She had, after all, sufficient

influence to cause the provost and bailies to be degraded from their

offices for this act of zeal.

The autumn of this year, the weather

was ‘richt guid and fair.’ In the winter quarter, the weather was still

fair, and there was ‘peace and rest in all Scotland.’— C. F

Dec 16

William Guild was convicted, notwithstanding his being a minor and of weak

mind, of ‘the thieftous stealing and taking forth of the purse of

Elizabeth Danielstoue, the spouse of Niel Laing, hinging upon her apron .

. . . she being upon the High Street, standing at the krame of William

Speir . . . . in communing with him, the time of the putting of ane string

to ane penner and inkhorn, whilk she had coft [bought] fra the said kramer,

of ane signet of gold, ane other signet of gold set with ane cornelian,

ane gold ring set with ane great sapphire, ane other gold ring with ane

sapphire formit like ane heart, ane gold ring set with ane turquois, ane

small double gold ring set with ane diamond and ane ruby, ane auld

angel-noble, and ane cusset ducat.’—Pit. This account of the contents of

Mrs Laing’s purse, in connection with the decorations of the fifty young

citizens who convoyed the queen in her procession through the city, raises

unexpected ideas as to the means and taste of the middle classes in 1561.

Dec 24, 1561

Mr William Balfour, indweller in Leith, was convicted of breaking the

queen’s proclamation for the protection of the reformed religion. One of

his acts—’ He, accompanied with certain wicked persons . . . . upon set

purpose, came to the parish kirk of Edinburgh, callit Sanct Giles Kirk,

where John Cairns was examining the common people of the burgh, before the

last communion . . . . and the said John, demanding of ane poor woman,

"Gif she had ony hope of salvation by her awn good works," he, the said Mr

William, in despiteful manlier and with thrawn countenance, having

naething to do in that kirk but to trouble the said examination, said to

the said John thir words: "Thou demands of that woman the thing whilk thou

nor nane of thy opinion allows or keeps." And, after gentle admonition

made to him by the said John, he said to him alsae thir words: "Thou art

ane very knave, and thy doctrine is very false, as all your doctrine and

teaching is." And therewith laid his band upon his weapons, and provoking

battle; doing therethrough purposely that was in him to have raisit tumult

amang the inhabitants of this burgh.’—Pit.

Jan 1, 1562

Alexander Scott, a poet of that time, sometimes called the Scottish

Anacreon, because he sung so much of love, sent Aine New

Year Gift

to the queen, in the form of a poetical address in

twenty-eight stanzas. ‘Welcome, illustrate lady, and our queen!’ it

begins. ‘This year sail richt and reason rule the rod ‘—‘ this year sall

be of peace, tranquillity, and rest!’ says the sanguine bard, speaking

from his wishes rather than a contemplation of known facts. He calls on

Mary to found on the four cardinal virtues, to cleave to Christ, and be

the ‘protectrice of the puir.’ ‘Stanch all strife ‘—‘the pulling down of

policy reprove.’

‘At Cross gar cry by open

proclamation,

Under great pains, that neither lie

nor she

Of haly writ have ony disputation,

But letterit men or learnit clerks thereto;

For limmer lads and little lasses low

Will argue baith with bishops, priests, and frier;

To danton this thou has eneuch to do,

God give thee grace against this guid new year !‘

Mary would probably feel the force

of the seventh line of this stanza.

With commendable prudence, seeing he

was addressing a papist queen, honest Alexander says:

‘With mess nor matins noways will I

mell,

To judge them justly passes my ingine;

They guide nocht ill that governs weel themsel.’

Yet he deems himself at liberty to

remark—doubtless suspecting that Mary would not be much displeased—that

instead of old idols has now come in another called Covetice, under

whose auspices, certain persons, while

'Singing Sanct David's psalter on

their books,'

arc found

‘Rugging and ryving up kirk rents

like rooks?

‘Protestants,’ he goes on to say,

‘takes the friers’ antetume,’

[repose]

Ready receivers, but to render nocht.’

On this Lord Hailes remarks: ‘The

reformed clergy expected that the tithes would be applied to charitable

uses, to the advancement of learning and the maintenance of the ministry.

But the nobility, when they themselves had become the exactors, saw

nothing rigorous in the payment of tithes, and derided those

devout imaginations.’

In one verse of his poem, Scott makes pointed

allusion to certain prophecies which seemed to assign a brilliant future

to Mary:

‘If saws be

sooth to shaw thy

celsitude,

What bairn should brook all Britain by the sea,

The prophecy expressly does conclude

The French wife of the Bruce’s blood should be:

Thou art by line from

him the ninth degree,

And was King

Francis’ perty maik and peer;

So by descent the same should spring of thee,

By grace of God

against this good new year.’

The poet here undoubtedly had in view a prediction

which occurs in a rude metrical tract printed at Edinburgh by Robert

Waldegrave in 1603, under the title, ‘The Whole Prophesies of Scotland,

England, and somepart of France and Denmark, prophesied by mervelious

Merling, Beid, Bertlingtoun, Thomas Rymour, Waldhave, &c., all according

in one.’ These so-called

prophecies are unintelligible rhapsodies about lions, dragons, foumarts,

conflicts of knights, of armies, and of navies—how there should be

fighting on a moor beside a cross, till by the multitude of slain the crow

should not find where the cross stood—how the dead shall rise, ‘and that

shall be wonder ‘—how

‘When the man in the moon is

most in his might,

Then shall Dunbarton turn up that is down,

And the mouth of Arran both at one time,

And the lord with the lucken hand his life

shall he lose—’

and much more of the like kind.

From the style of the verse, which

is in general alliterative, as well as some of the allusions, it may be

surmised that these

prophecies were written in the minority of James V., on

the basis of obscure popular sayings attributed to Merlin, Rymour, and

other early sages. The special passage which Alexander Scott refers to was

in Rymour’s prophecies, but also given in a slightly different form in

those of Bertlingtoun:

‘A French wife shall bear the son,

Shall rule all Britain to the sea,

That of the Bruce’s blood shall come,

As near as to the ninth degree?

There can be no doubt that it is

applicable to Queen Mary, who was a French wife, and in the ninth degree

of descent from Bruce; and did we know for certain that it formed a part

of the prophecies made up in the minority of her father, it would be

remarkable. But the probability is, that the verse was a recent addition

to the old rhymes, a mere conjecture formed in the view of the possibility

and the hope that a child of Mary would succeed to the English crown at

the close of Elizabeth’s life. What makes the allusion of Scott chiefly

worthy of notice, is the knowledge it gives us of the public mind being

then possessed by such soothsayings. It certainly was so, to a degree and

with effects beyond what we now may readily imagine.

While Scotland was noted in the eyes

of foreigners as a barren land—Shakspeale comparing it for nakedness to

the palm of the hand—its own people were fain to believe and eager to

boast that it was rich in minerals. In

1511, 1512, and 1513, James IV.

had gold-mines

worked on Crawford Muir, in the upper ward of Lanarkshire—a peculiarly

sterile tract, scarcely any part of which is less than a thousand feet

above the sea. In the royal accounts for those years, there are payments

to Sir James Pettigrew, who seems to have been chief of the enterprise, to

Simon Northberge, the master-finer, Andrew Ireland, the finer, and Gerald

Essemer, a Dutchman, the melter of the mine. Under the same king, in 1512,

a lead-mine was wrought at Wanlock-head, on the other side of the same

group of hills in Dumfriesshire. The operations, probably interrupted by

the disaster of Flodden, were resumed in 1526, under James V., who gave a

company of Germans a grant of the mines of Scotland for forty-three years.

Leslie tells us that these Germans, with the characteristic perseverance

of their countrymen, toiled laboriously at gold-digging for many months in

the surface alluvia of the moor, and obtained a considerable amount of

gold, but not enough, we suspect, to remunerate the labour: otherwise the

work would surely have been continued.

We shall find that the search for

the precious metals in the mountainous district at the head of the vales

of the Clyde and Nith, did not now finally cease, but that it never proved

remunerative work. On the other hand, the lead-mines of the district have

for centuries, and down to the present day, borne a conspicuous place in

the economy of Scotland. It must be interesting to see the traces of the

first efforts to get at

‘the wealth

Hopetoun’s high mountains fill.'

John Acheson, master-cunyer, and

John Aslowan, burgess of Edinburgh, now completed an arrangement with

Queen Mary, by virtue of which they had licence to work the lead-mines of

Glen-goner and Wanlock-head, and carry as much as twenty thousand

stone-weight of the ore to Flanders, or other foreign countries, for which

they bound themselves to deliver at the queen’s cunyie-house before the

1st of August next, forty-five ounces of fine silver for every thousand

stone-weight of the ore, ‘extending in the hale to nine hundred unces of

utter fine silver.’

Acheson and Aslowan were continuing

to work these mines in August 1565, when the queen and her husband, King

Henry, granted a licence to John, Earl of Athole, ‘to win forty thousand

trone stane wecht, counting six score stanes for ilk hundred, of lead ore,

and mair, gif the same may guidly be won, within the nether lead hole of

Glengoner and Wanlock.’ The earl agreed to pay to their majesties in

requital fifty ounces of fine silver for every thousand stone-weight of

the ore.—P. C. R.

How the enterprise of Acheson and

Aslowan ultimately succeeded does not appear. We suspect that, to some

extent, it prospered, as the name Sloane, which seems the same as Aslowan,

continued to flourish at Wanlock-head so late as the days of Burns.

A similar licence, on similar terms,

was granted by the king and queen to James Carmichael, Master James

Lindsay, and Andrew Stevenson, burgesses of Edinburgh, referring, however,

to any part of the realm save ‘the mine and werk of Glengoner and Wanlock.’

The Lord James, newly created Earl

of Mar (subsequently of Moray), ‘was married upon Annas Keith, daughter to

William Earl Marischal, in the kirk of Sanct Geil in Edinburgh, with sic

solemnity as the like has not been seen before; the hale nobility of this

realm being there present, and convoyit them down to Holyroodhouse, where

the banquet was made, and the queen’s grace thereat.’ The solemnity

was of a kind which seems rather frisky for so zealous an upholder of the

presbyterian cause. ‘At even, after great and divers balling, and casting

of fire-balls, fire-spears, and running with horses,’ the queen created

sundry knights. Next day, ‘at even, the queen’s grace and the remaining

lords came up in ane honourable manner frae the palace of Holyroodhouse to

the Cardinal’s lodging in the Blackfrier Wynd, whilk was preparit and hung

maist honourably; and there her hieness suppit, and the rest with her.

After supper, the honest young men in the town [the youths of the upper

classes] came with ane convoy to her, and other some came with merschance,

well accouterit in maskery, and thereafter departit to the said

palace.’—.D. O.

Feb

There was ‘meikle snaw in all parts; mony deer and roes slain.’

—C. F.

1562, Apr

The queen was at St Andrews, inquiring into a conspiracy of which the Duke

of Chatelherault and the Earl of Bothwell had been accused by the Duke’s

son, the Earl of Arran. In the midst of the affair, Arran proved to be ‘phrenetick.’

On the 4th of May, ‘my Lords Arran, Bothwell, and the Commendator of

Kilwinning came fra St Andrews to the burgh of Edinburgh in this manner;

that is to say, my Lord Arran was convoyit in the queen’s grace’s

coach, because of the phrenesy aforesaid, and the Earl of Bothwell and

my Lord Commendator of Kilwinning rade, eonvoyit with twenty-four

horsemen, whereof was principal Captain Stewart, captain of the queen’s

guard.’—D. O.

This is not the first notice of a

travelling vehicle that occurs in our national domestic history. Several

payments in connection with a chariot belonging to the late Queen Mary de

Guise, so early as 1538, occur in the lord-treasurer’s books. [In July

1538, there is an entry in the treasurer’s books, of 14s. ‘to Alexander

Naper for mending of the Queen’s sadill and her cheriot, in Sanet

Androis.’ In January 1541—2, there is another: ‘To mend the Quenis cheriot

vi¼ elnis blak velvet, £16, 17s. 6d.’ Besides something for cramosie,

satin, and fringes.] It is not, however, likely that either the chariot of

the one queen or the coach of the other was a wheeled vehicle, as, if we

may trust to an authority about to be quoted, such a convenience was as

yet unknown even in England.

‘In the year 1564, Guilliam Boonen, a Dutchman, became

the queen’s coachman, and was the first that brought the use of coaches

into England. And after a while, divers great ladies, with as great

jealousy of the queen’s displeasure, made them coaches, and rid in them up

and down the countries, to the great admiration of all the beholders; but

then, by little and little, they grew usual among the nobility and others

of sort, and within twenty years became a great trade of coachmaking.

‘And about that time began long waggons to come in use,

such as now come to London from Canterbury, Norwich, Ipswich, Gloucester,

&c., with passengers and commodities. Lastly, even at this time (1605)

began the ordinary use of carouches.’—Howes’s Chronicle.

The author of the Memorie of the Somervilles—who,

however, lived in the reign of Charles II., and probably wrote from

tradition only—says that the Regent Morton used a coach, which was the

second introduced into Scotland, the first being one which

Alexander Lord Seaton brought from France, when Queen Mary returned from

that country. It is to be remarked that the Lord Seaton of that day was

George, not Alexander; and it is evident that Mary did not use a coach on

her landing, or at her ceremonial entry into Edinburgh.

To turn for a moment to one of the remoter and wilder

parts of the country—John Mackenzie of Kintail ‘was a great courtier with

Queen Mary. He feued much of the lands of Brae Ross. When the queen sent

her servants to know the condition of the gentry of Ross, they came to his

house of Killin; but before their coming he had gotten intelligence that

it was to find out the condition of the gentry of Ross that they were

coming; whilk made’ him cause his servants to put ane great fire of fresh

arn [alder] wood when they came, to make a great reek; also he caused kill

a great bull in their presence; whilk was put altogether into ane kettle

to their supper. When the supper came, there were a half-dozen great dogs

present, to sup the broth of the bull, whilk put all the house

through-other with their tulyie. When they ended the supper, ilk ane lay

where they were. The gentlemen thought they had gotten purgatory on earth,

and came away as soon as it was day; but when they came to the houses of

Balnagowan, and Foulis, and Milton, they were feasted like princes.

‘When they went back to the queen, she asked who were

the ablest men they saw in Ross. They answered: "They were all able men,

except that man that was her majesty’s great courtier, Mackenzie—that he

did both eat and lie with his dogs." "Truly," said the queen, "it were a

pity of his poverty—he is the best man of them all." Then the queen did

call for all the gentry of Ross to take their land in feu, when Mackenzie

got the cheap feu, and more for his thousand merks than any of the rest

got for five."

Sep 28

This day commenced a famous disputation between John Knox and Quintin

Kennedy, abbot of Crossraguel, concerning the doctrines of popery. Kennedy

was uncle to the Earl of Cassius, a young Protestant noble, and the

greatest man in the west of Scotland. The birth and ecclesiastical rank of

the abbot made him an important person in his province, and he possessed

both zeal for the ancient religion and talents to set it in its fairest

light. Early in September, John Knox, coming into Ayrshire for certain

objects connected with the Protestant cause, found that Abbot Kennedy had

set forth, in the church of Kirkoswald, articles in support of the

Catholic faith, which he was willing to defend. The fiery reformer

immediately resolved to take up the challenge; and after a tedious

correspondence between the two regarding the place, time, and number to be

present, they met in the house of the provost of the collegiate church of

Maybole, under the sanction of the Earl of Cassillis, and with forty

persons on each side. The conference commenced at eight in the morning,

being opened by John Knox with a prayer, which Kennedy admitted to be

‘weel said.’

We can imagine the forty supporters of Kennedy full of

joyful anticipation as to the defeat which their champion was to give the

unpolite heretic Knox, and the company of the latter not less hopeful

regarding the triumph which he was to achieve over the luxurious abbot.

Acts of parliament had done their best to put down the old church, and

still it had some obstinate adherents; but now comes the valiant reformer,

with pure argument from Scripture, to sweep one of these recusants off the

face of the earth, and leave the rest without an excuse for their

obstinacy. Now are the mass, purgatory, worship of saints, and other

popish doctrines, to be finally put down. If such were the anticipations

they were doomed to a sad disappointment. The disputation proved to be the

very type of all similar wranglings which have since taken place between

the two parties.

It will scarcely be believed, but there is only too

little reason why it should not, that three days were consumed by these

redoubted controversialists in debating one question. The warrant of the

abbot for considering the mass as a sacrifice was the priesthood and

oblation of Melchizedek. ‘The Psalmist,’ said he, ‘and als the apostle St

Paul affirms our Saviour to be ane priest for ever according to the order

of Melchizedek, wha made oblation and sacrifice of bread and wine unto

God, as the Scripture plainly teacheth us... Read all the evangel wha

pleases, he sall find in no place of the evangel where our Saviour uses

the priesthood of Melchizedek, declaring himself to be ane priest after

the order of Melchizedek, but in the Latter Supper, where he made oblation

of his precious body and blude under the form of bread and wine

prefigurate by the oblation of Melchizedek: then are we compelled to

affirm that our Saviour made oblation of his body and blude in the Latter

Supper, or else he was not ane priest according to the order of

Melchizedek, which is express against the Scripture.’

To this Knox answered that Scripture gives no warrant

for supposing that Melchizedek offered bread and wine unto Abraham, and

therefore the abbot’s warrant fails. The abbot called on him to prove that

Melchizedek did not do so. Knox protested that he was not bound to prove a

negative. ‘For what, then,’ says Kennedy, ‘did Melchizedek bring out the

bread and wine?’ Knox said, that though he was not bound to answer this

question, yet he believed the bread and wine were brought out to refresh

Abraham and his men. In barren wranglings on this point were nearly the

whole three days spent; and, for anything we can see, the disputation

might have been still further protracted, but for an opportune

circumstance. Strange to say—looking at what Maybole now is—it broke down

under the burden of eighty strangers in three days! They had to disperse

for lack of provisions.’

Nov

There raged at this time in Edinburgh a disease called the New

Acquaintance. The queen and most of her courtiers had it; it spared

neither lord nor lady, French nor English. ‘It is a pain in their heads

that have it, and a soreness in their stomachs, with a great cough; it

remaineth with some longer, with others shorter time, as it findeth apt

bodies for the nature of the disease." Most probably, this disorder was

the same as that now recognised as the influenza.

1563, May 19

Sir John Arthur, a priest, was indicted for baptising and marrying several

persons ‘in the auld and abominable papist manner.’ Here and there, the

old church had still some adherents who preferred such ministrations to

any other. It appears that Hugh and David Kennedy came with two hundred

followers, ‘boden in effeir of weir;’ that is, with jacks, spears, guns,

and other weapons; to the parish kirk of Kirkoswald and the college kirk

of Maybole, and there ministered and abused ‘the sacraments of haly kirk,

otherwise and after ane other manner nor by public and general order of

this realm.’ The archbishop of St Andrews in like manner came, with a

number of friends, to the Abbey Kirk of Paisley, ‘and openly, publicly,

and plainly took auricular confession of the said persons, in the said

kirk, town, kirk-yard, chalmers, barns, middings, and killogies thereof.’—Pit.

‘After great debate, reasoning, and communication had in the council by

the Protestants, wha was bent even to the death against the said

archbishop and others kirkmen, the archbishop passed to the Tolbooth, and

became in the queen’s will; and sae the queen’s grace commandit him to

pass to the Castle of Edinburgh induring her will, to appease the

furiosity foresaid.’—D. O. The other offenders also made

submission, and were assigned to various places of confinement. William

Semple of Thirdpart and Michael Nasmyth of Posso afterwards gave caution

to the extent of £3000 for the future good behaviour of the archbishop.—.

Pit.

June 4

In the parliament now sitting, some noticeable acts were passed. One

decreed that ‘nae person carry forth of this realm ony gold or silver,

under pain of escheating of the same and of all the remainder of their

moveable guids,’ merchants going abroad to carry only as much as they

strictly require for their travelling expenses. Another enacted, that ‘nae

person take upon hand to use ony manner of witchcrafts, sorcery, or

necromancy, nor give themselves furth to have ony sic craft or knowledge

thercof there-through abusing the people;’ also, that ‘nae person seek ony

help, response, or consultation at ony sic users or abusers of witchcrafts

. . . under the pain of death? This is the statute under which all the

subsequent witch-trials took place.

A third statute, reciting that much coal is now carried

forth of the realm, often as mere ballast for ships, causing ‘a maist

exorbitant dearth and scantiness of fuel,’ forbade further exportations of

the article, under strong penalties. In those early days, coal was only

dug in places where it cropped out or could be got with little trouble. As

yet, no special mechanical arrangements for excavating it had come into

use. The comparatively small quantity of the mineral used in Edinburgh—for

there peat was the reigning fuel—was brought from Tranent, nine miles off,

in creels on horses’ backs. The above enactment probably referred

to some partial and temporary failure of the small supply then required.

It never occurred to our simple ancestors, that to export a native

produce, such as coal, and get money in return, was tending to enrich the

country, and in all circumstances deserved encouragement instead of

prohibition.

July 2

Henry Sinclair, Bishop of Ross and President of the Court of Session—’ a

cunning and lettered man as there was,’ remarkable for his ‘singular

intelligence in theology and likewise in the laws,’ according to the

Diurnal of Occurrents’ ane

perfect hypocrite and conjured enemy to Christ Jesus,’ according to John

Knox—left Scotland for Paris, ‘to get remede of ane confirmed stane.’ This

would imply that there was not then in our island a person qualified to

perform the operation of lithotomy. The reverend father was lithotomised

by Laurentius, a celebrated surgeon; but, fevering after the operation, he

died in January 1564—5: in the words of Knox, ‘God strake him according to

his deservings.’

At the same time there were not wanting amongst us

pretenders to the surgical art. In this very month, Robert Henderson

attracted the favourable notice of the town-council of Edinburgh by

performing sundry wonderful cures—namely, healing a man whose hands had

been cut off, a man and woman who had been run through the body with

swords by the French, and a woman understood to have been suffocated, and

who had lain two days in her grave. The council ordered Robert twenty

merks as a reward.

Sep 13

Two gentlemen became sureties in Edinburgh for Marion Carruthers,

co-heiress of Mousewald, in Dumfriesshire, ‘that she shall not marry ane

chief traitor nor other broken man of the country,’ under pain of £1000

(Pit)—a large sum to stake upon a young lady’s will.

This was a year of dearth throughout Scotland; wheat

being six pounds the boll, oats fifty shillings, a draught-ox twenty merks,

and a wedder thirty shillings. ‘All things apperteining to the

sustentation of man in triple and more exceeded their accustomed prices.’

Knox, who notes these facts, remarks that the famine was most severe in

the north, where the queen had travelled in the preceding autumn: many

died there. ‘So did God, according to the threatening of his law, punish

the idolatry of our wicked queen, and our ingratitude, that suffered her

to defile the land with that abomination again [the mass]... The riotous

feasting used in court and country wherever that wicked woman repaired,

provoked God to strike the staff of breid, and to give his malediction

upon the fruits of the earth.’

It was of the frame of the reformer’s ideas, that a

judgment would be sent upon the poor for the errors of their ruler, and

that this judgment would be intensified in a particular district merely

because the ruler had given it her personal presence. He failed to

observe, or threw aside, the fact, that the same famine prevailed in

England, where a queen entirely agreeable to him and his friends was now

reigning, and certainly indulging in not a few banquetings. Theories of

this kind sometimes prove to be two-edged swords, that will strike either

way. It might have been replied to him: ‘Accepting your theory that

nations, besides suffering from the simple misgovernment of their rulers,

are punished for their personal offences, what shall we say of the

Protestant Elizabeth, whose people now suffer not merely under famine, as

the Scotch are doing, but are visited by a dreadful pestilence besides,

from which Scotland is exempt?’ [In England, the spring of 1562 had been

marked by excessive rains, and the harvest was consequently bad. Towards

the end of the year, plague broke out in the crowded and harassed

population of Havre, in France, then undergoing a siege, and from the

garrison it was imparted to England, which had been prepared for its

reception by the famine. There it prevailed throughout the whole year

1563, carrying off 20,000 persons in London alone. ‘The poor citizens,’

says Stowe, ‘were this year plagued with a threefold plague—pestilence,

dearth of money, and dearth of victuals; the misery whereof were too long

here to write. No doubt the poor remember it.’ On account of the plague at

Michaelmas, no term was kept, and there was no lord-mayor’s dinner!

The plague spread into Germany, where it was estimated to have carried off

300,000 persons.]

1564, Jan 20

‘God from heaven, and upon the face of the earth, gave declaration that he

was offended at the iniquity that was committed within this realm; for,

upon the 20th day of January, there fell weet in great abundance, whilk in

the falling freezit so vehemently, that the earth was but ane sheet of

ice. The fowls both great and small freezit, and micht not flie: mony

died, and some were taken and laid beside the fire, that their feathers

might resolve. And in that same month, the sea stood still, as was clearly

observed, and neither ebbed nor flowed the space of twenty-four hours.’—Knox.

Feb 15 and 18

In the ensuing month meteorological signs even more alarming to the great

reformer took place. There were seen in the firmament, says he, ‘battles

arrayit, spears and other weapons, and as it had been the joining of two

armies. Thir things were not only observed, but also spoken and constantly

affirmed by men of judgment and credit.’ Nevertheless, he adds, ‘the queen

and our court made merry.’

The reformer considered these appearances as

declarations of divine wrath against the iniquity of the land, and he is

evidently solicitous to establish them upon good evidence. There can be no

difficulty in admitting the facts he refers to. The debate must be as to

what the facts were. Most probably they were resolvable into a simple

example of the aurora borealis.

The crimes of unruly passion and of superstition

predominated in this age; but those of dexterous selfishness were not

unknown.

Feb

Thomas Peebles, goldsmith in Edinburgh, was convicted of forging

coin-stamps and uttering false coin—namely, Testons, Half-lesions, Non-sunts,

and Lions or Hardheads. It appeared that he had given

some of his false hardheads to a poor woman as the price of a burden of

coal. With this money she came to the market to buy some necessary

articles, and was instantly challenged for passing false coin. ‘The said

Thomas being named by her to be her warrant, and deliverer of the said

false coin to her, David Symmer and other bailies of the burgh of

Edinburgh come with her to the said Thomas’s chalmer, to search him for

trial of the verity. He held the door of his said chalmer close upon him,

and wald not suffer them to enter, while [till] they brake up the door

thereof upon him, and entered perforce therein; and the said Thomas, being

inquired if he had given the said poor woman the said lions, for the price

of her coals, confessit the same; and his chalmer being searched, there

was divers of the said irons, as well sunken and unsunken, together with

the said false testons, &c., funden in the same, and confessit to be made

and graven by him and his colleagues.’ Thomas was condemned to be hanged,

and to have his property escheat to the queen.—Pit.

May 22

In consequence of the slaughter of the Laird of Cessford, in an encounter

with the Laird of Bucclench, at Melrose, in 1526, a feud had ever since

raged between their respective dependents, the Kerrs and Scotts. In 1529,

there had been an effort to put an end to this broil by an engagement

between Walter Kerr of Cessford, Andrew Kerr of Ferniehirst, Mark Kerr of

Dolphinston, George Kerr, tutor of Cessford, and Andrew Kerr of

Primsideloch, for themselves and kin on the one part, and Walter Scott of

Branxholm, knight, with sundry other gentlemen of his clan on the other

side, whereby the latter became bound to perform the four pilgrimages of

Scotland— that is, to the churches of Melrose, Dundee, Scone, and Paisley—

as a reparation for the slaughter. Bad blood being nevertheless kept up,

Sir Walter Scott of Branxholm, Laird of Buccleuch, was slain on the

streets of Edinburgh by Cessford, in 1552.

At the date now under attention, a meeting of the heads

of the two houses took place in Edinburgh, and a contract was drawn up,

setting forth certain terms of agreement, and arranging that, ‘for the

mair sure removing, stanching, and away-putting of all inimity, hatrent,

and grudge standing and conceivit betwin the said parties, through the

unhappy slaughter of the umwhile Sir Walter Scott of Branksome, knight,

and for the better continuance of amity, favour, and friendship, amangs

them in time coming, the said Sir Walter Kerr of Cessford sail, upon the

23 day of March instant, come to the perish kirk of Edinburgh, now

commonly callit Sanct Giles’s Kirk, and there, before noon, in sight of

the people present for the time, reverently upon his knees ask God mercy

of the slaughter aforesaid, and sic like ask forgiveness of the same fra

the said Laird of Buccleuch and his friends whilk sail happen to be

present; and thereafter promise, in the name and fear of God, that he and

his friends sail truly keep their part of this present contract, and sail

stand true friends to the said Laird of Buccleuch and his friends in all

time coming: the whilk the said Laird of Buccleuch sail reverently accept

and receive, and promise, in the fear of God, to remit his grudge, and

never remember the same.’ A subsequent part of the agreement was, that the

son of Cessford should marry a sister of Buccleuch, and Sir Andrew Ker of

Fawdonside another sister, both without portion.’

This singular meeting would of course take place, but

with what effect may well be doubted. It appears that the feud which had

begun in 1526 still remained in force in 1596, ‘when both chieftains

paraded the streets of Edinburgh with their followers, and it was expected

their first meeting would decide their quarrel.’

Mar 24

At a time when the most prominent events were clan-quarrels and the rough

doings connected with the trampling out of an old religion, it is pleasant

to trace even speculative attempts to enlarge the material resources and

advance the primary interests of the country.

At the date noted, the queen granted to John Stewart of

Tarlair, and William Stewart his son, licence to win all kinds of metallic

ores from the country between Tay and Orkney, on the condition of paying

one stone of ore for every ten won; and this arrangement to last for nine

years, during the first two of which their work was to be free, ‘in

respect of their invention and great charges made, and to be made, in

outreeking of the same.’ In the event of their finding any gold and silver

where none were ever found before, they had the same licence, with only

this condition, that the product was to be brought to her majesty’s cunyie-house,

‘the unce of gold for ten pund, and the unce of utter fine silver for

24s.’ It was too early for such an enterprise, and we hear no more of it

in the hands of the two Stewarts of Tarlair.

1564, March

John Knox, at the age of fifty-eight, entered into the state of wedlock

for the second time, by marrying Margaret Stewart, daughter of Lord

Ochiltree. She proved a good wife to the old man, and survived him. The

circumstance of a young woman of rank, with royal blood in her veins—for

such was the case—accepting an elderly husband so far below her degree,

did not fail to excite remark; and John’s papist enemies could not account

for it otherwise than by a supposition of the black art having been

employed. The affair is thus adverted to by the reformer’s shameless

enemy, Nicol Burne: ‘A little after he did pursue to have alliance with

the honourable house of Ochiltree, of the king’s majesty’s awn bluid.

Riding there with ane great court [cortege], on ane trim gelding, nocht

like ane prophet or ane auld decrepit priest, as he was, but like as he

had been ane of the bluid royal, with his bands of taffeta fastenit with

golden rings and precious stanes: and, as is plainly reportit in the

country, by sorcery and witchcraft, [he] did sae allure that puir

gentlewoman, that she could not live without him; whilk appears to be of

great probability, she being ane damsel of noble bluid, and he ane auld

decrepit creature of maist base degree, sae that sic ane noble house could

not have degenerate sae far, except John Knox had interposed the power of

his master the devil, wha, as he transfigures himself sometimes as ane

angel of licht, sae he causit John Knox appear ane of the maist noble and

lusty men that could be found in the warld."

May 17

‘. . . . the Lord Fleming married the Lord Ross’s eldest daughter, wha was

heretrix both of Ross and Halket; and the banquet was made in the park of

Holyroodhouse, under Arthur’s Seat, at the end of the loch, where great

triumphs was made, the queen’s grace being present, and the king of

Swethland’s ambassador being then in Scotland, with many other nobles.’—

Mar.

In the romantic valley between Arthur’s Seat and

Salisbury Crags, there is still traceable a dam by which the natural

drainage had been confined, so as to form a lake. It was probably at the

end of that sheet of water that the banquet was set forth for Lord and

Lady Fleming’s wedding. The incident is so pleasantly picturesque, and

associates Mary so agreeably with one of her subjects, that it is

gratifying to reflect on Lord Fleming proving a steady friend to the queen

throughout her subsequent troubles. He stoutly maintained Dumbarton Castle

in her favour against the Regents, and against Elizabeth’s general, Sir

William Drury; nor was it taken from him except by stratagem.’

Aug

At the beginning of this month, Queen Mary paid a visit of pleasure to the

Highlands of Perthshire, where the Earl of Athole was her entertainer. It

is understood that Glen Tilt was the scene of a grand hunt, in the

characteristic style of the country, at which the queen was present, and

of which an account has been preserved to us by a scholarly personage who

was in the royal train. ‘In the year 1563,’ says he (mistaking the year),

‘the Earl of Athole, a prince of the blood-royal, had, with much trouble

and vast expense, a hunting-match for the entertainment of our most

illustrious and most gracious queen. Our people call this a royal hunting.

I was then,’ says William Barclay, ‘a young man, and was present on the

occasion. Two thousand Highlander; of wild Scotch, as you call them here,

were employed to drive to the hunting-ground all the deer from the woods

and hills of Athole, Badenoch, Mar, Murray, and the counties about. As

these Highlanders use a light dress, and are very swift of foot, they went

up and down so nimbly that in less than two months’ time they brought

together 2000 red deer, besides roes and fallow-deer. The queen, the great

men, and others, were in a glen when all the deer were brought before

them. Believe me, the whole body of them moved forward in something like

battle order. This sight still strikes me, and ever will, for they had a

leader whom they followed close wherever he moved. This leader was a very

fine stag, with a very high head. The sight delighted the queen very much;

but she soon had occasion for fear, upon the earl’s (who had been

accustomed to such sights) addressing her thus: "Do you observe that stag

who is foremost of the herd? There is danger from that stag; for if either

fear or rage should force him from the ridge of that hill, let every one

look to himself, for none of us will be out of the way of harm; for the

rest will follow this one, and having thrown us under foot, they will open

a passage to this hill behind us." What happened a moment after confirmed

this opinion; for the queen ordered one of the best dogs to be let loose

upon a wolf;’ this the dog pursue; the leading stag was frightened, he

flies by the same way he had come there, the rest rush after him, and

break out where the thickest body of the Highlanders was. They had nothing

for it but to throw themselves flat on the heath, and to allow the deer to

pass over them. It was told the queen that several of the Highlanders had

been wounded, and that two or three had been killed outright; and the

whole body had got off, had not the Highlanders, by their skill in

hunting, fallen upon a stratagem to cut off the rear from the main body.

It was of those that had been separated that the queen’s dogs, and those

of the nobility, made slaughter. There were killed that day 360 deer, 4ith

five wolves and some roes.’

[‘William Barclay, De Regno et Regali Potestate

adversus Monarchomachos. Parisiis, 1600. This author was a native of

Aberdeenshire, but finally settled at Angers, in France, as Professor of

civil Law in the University there. He died in 1604.

Bishop Geddes, in introducing this extract from

Barclay’s forgotten work to the notice of the Society of the Antiquaries

of Scotland (1782), remarks that a still more grand entertainment of the

same kind was given in 1529 to King James V., his mother, Queen Margaret,

and the pope’s legate, by the then Earl of Athole, and that an account of

the affair has been preserved in Lindsay of Pitscottie’s History of

Scotland. The venerable bishop adds: ‘Need I take notice that the

hunting described by Barclay bears some resemblance to the batidas

of the present king of Spain, where several huntsmen form a line and drive

the deer through a narrow pass, at one side of which the king, with some

attendants, has his post, in a green hut of boughs, and slaughters the

poor animals as they come out almost as fast as charged guns can be put

into his hand and he fire them. These are things sufficiently known; and

the same manner of stag-hunting is practised in Italy, Germany, and other

parts of Europe.]

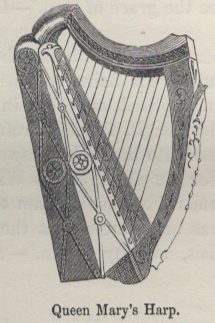

The queen, in the course of her excursion, is believed

to have taken an interest in the native music of the Highlands, in which,

as in Ireland, the harp bore a distinguished part. It is even reported

that a kind of competition amongst the native harpers took place in her

presence, at which she adjudged the victory to Beatrix Gardyn, of Banchory,

Aberdeenshire. Certain it is, that the Robertsons of Lude possessed a harp

of antique form, which family tradition represented as having come to them

through a descendant of Beatrix Gardyn, who had married a Robertson of

Lude; and the same authority regarded this harp with veneration, as having

been the prize conferred on the fair Beatrix by Queen Mary, for her

superior excellence as a performer on the instrument. Queen Mary’s harp,

as it is called, is now in the possession of Mr Stewart of Dalguise. It is

a small instrument compared with the modern harp, being fitted for

twenty-eight strings, the longest extending twenty-four inches, the

shortest two and a half. There had once been gems set in it, and also, it

is supposed, a portrait of the queen. It was strung anew and played upon

in 1806.

This summer there was ‘guid cheap of victuals in all

parts. The year afore, the boll of meal gave five merk, and this summer it

was 18s. There ye may see the grace of God.’—C. F.

Oct

‘.... William Smibert, being callit before the kirk [session of the

Canongate] why he sufferit his bairn to be unbaptised, answers: "No, I

have my bairn baptised, and that in the queen’s grace’s chapel," because,

as he allegit, the kirk refusit him; and being requirit wha was witness

unto the child, answers: "I will show no man at this time." For the whilk,

James Wilkie, bailie, assistant with the kirk, commands the said William

to be halden in ward until he declare wha was his witness, that the kirk

may be assurit the bairn to be baptisit, and by wham.’—Kirk-session Rec.

of Canongate.

1565, Jan

The queen making a progress in Fife caused so much banqueting as to

produce a scarcity of wild-fowl: ‘partridges were sold for a crown

a-piece.’-—Knox.

Apr 1

The communion was administered in Edinburgh, and as it was near Easter,

the few remaining Catholics met at mass. The reformed clergy were on the

alert, and seized the priest, Sir James Carvet, as he was coming from the

house where he had officiated. Knox tells us with what an absurd degree of

leniency the offender was treated. They ‘conveyed him,’ says he, ‘together

with the master of the house, and one or two more of the assistants, to

the Tolbooth, and immediately revested him with all his garments upon him,

and so carried him to the Market Cross, where they set him on high,

binding the chalice in his hand, and himself tied fast to the said Cross,

where he tarried the space of one hour; during which time the boys

served him with his Easter eggs.

‘The next day, Carvet with his assistants were

accused and convinced by an assize, according to the act of parliament;

and, albeit for the same offence he deserved death, yet, for all

punishment, he was set upon the Market Cross for the space of three or

four hours, the hangman standing by and keeping him, [while] the boys

and others were busy with eggs-casting.’

The queen sent an angry letter to the magistrates about

this business; from which ‘may be perceived how grievously the queen’s

majesty would have been offended if the mess-monger had been handled

according to his demerit’—that is, hanged. Knox.

April

A discovery of antique remains was made at Inveresk, near Musselburgh,

revealing the long-forgotten fact of the Romans once having had a

settlement on that fine spot. Randolph, the English resident at Mary’s

court, communicated some account of the discovery to the Earl of Bedford.

‘April 7, For certain there is found a cave beside Musselburgh, standing

upon a number of pillars, made of tile-stones curiously wrought,

signifying great antiquity, and strange monuments found in the same. This

cometh to my knowledge, besides the common report, by th’ assurance of

Alexander Clerk, who was there to see it, which I will myself do within

three or four days, and write unto your lordship the more certainty

thereof, for I will leave nothing of it unseen.’ ‘April 18, The cave found

beside Musselburgh, seemeth to be some monument of the Romans, by a stone

which was found, with these words graven upon him, APPOLLONI GRANNO Q. L.

SABINIANUS PROC. AUG. Divers short pillars set upright upon the ground,

covered with tile-stones, large and thick, torning into divers angles, and

certain places like unto chynes [chimneys] to avoid smoke. This is all I

can gather thereof.’

The reader will be amused at the difficulty which

Randolph seems to have felt in visiting a spot scarcely six miles from

Edinburgh. He will, however, be equally gratified to know that the queen

herself became interested in the preservation of the remains found on this

occasion. Her treasurer’s accounts contain an entry of twelvepence, paid

to ‘ane boy passand of Edinburgh, with ane charge of the queen’s grace,

direct to the bailies of Musselburgh, charging them to tak diligent heed

and attendance, that the monument of grit antiquity, new fundin, be nocht

demolishit nor broken down.’

The monument here spoken of was, in reality, an altar

dedicated to Apollo Grannicus, the Long-haired Apollo, by Sabinianus,

proconsul of Augustus, while the cave with pillars was the hypocaust or

heating-chamber of a bath, connected with a villa, of which further

remains were discovered in January 1783. The spot where the antiquities

were discovered in 1565 is occupied by the lawn in front of Inveresk

House. Camden reports the following as an accurate copy of the

inscription, made by Sir Peter Young, preceptor to King James VI.—’

APP0LLINI GRANNO Q. LUSIUS SABINIANUS PROC. AUG. VSSLVM.’—which is

thus extended and translated by the ingenious Robert Stuart in his

Caledonia Romana (1845): ‘Appollini Grannico Quintus Lusius Sabinianus

Proconsul Augusti, votum susceptum solvit lubens volens merito;’ that is,

‘To Appollo Granicus, Quintus Lusius Sabinianus, the Proconsul of Augustus

[dedicates this], a self-imposed vow, cheerfully performed.’

Napier alludes to the Inveresk altar in his commentary

on, the Apocalypse, and it appears to have attracted the attention of Ben

Jonson, when he was in Scotland in 1618. We last hear of it from Sir

Robert Sibbald, who died in 1711. In Gordon’s Itinerarium,

published a few years later, it is not noticed; wherefore it may be

conjectured that this interesting relic of antiquity was lost sight of or

destroyed about the beginning of the eighteenth century. |