|

THE tragic course of Scottish

history under the later Stuart kings resulted from the irreconcilable

antagonism of two ideas, each entertained as a principle absolute and

admitting of no compromise. On the one side, the people, with every fibre

hardened in its long struggle for religious liberty, held unflinchingly to

the divine right of conscience. On the other, the Royalists asserted no less

peremptorily the divine right of Kings. The people's claim meant in practice

the divine authority of the Presbyterian form of religion. And as the King,

in his capacity as I-leaven's vice-regent, claimed the right to impose

whatever form of religion commended itself to him, and as that form was not

Presbyterianism, there was no possibility of a compromise such as might have

led to a peaceful and harmoniously organised national life. For eleven years

under the Commonwealth and Protectorate, Scotland had experienced, for the

first time in her history, the domination of a foreign government whose rule

was orderly and not unjust, but which was yet in many respects uncongenial.

And when, in 1660, Charles II was restored to the throne, there were many

whose experience of the form of government set up by the Covenant led them

to accept with relief the return of the monarchy, and who looked hopefully

forward to happier times under the ancient line of Scottish kings.

But it soon appeared that the

old antagonism was to find no pacific solution, and that the policy of the

King and his advisers aimed at nothing less than the total extirpation of

the Covenant, a policy which would have been impracticable had not the

nobility turned Royalist and had not the Covenanters themselves been divided

by internal differences. The Recissory Act cancelled everything in the way

of legislation that the Covenant had accomplished, and Presbyterian

ministers had to forfeit their charges unless they brought themselves to

apply for collation by a bishop. There followed the long story of

persecution which has been described as "the most pitiful, the most

revolting, and at the same time the sublimest and most impressive page in

the national history." When we read the narrative of the torturings and the

violent deaths of those who remained faithful to the Covenant and who

refused to accept episcopacy and thus acknowledge Charles as the head of the

Church, and when we contrast their sufferings with the untroubled existence

that was open to them as an alternative, we cannot wonder if the majority

were ready to compromise and purchase peace and immunity on easy terms, nor

if many of the Presbyterian ministers took advantage of the Acts of

Indulgence to regain possession of their charges. While the dragoons were

scouring the moors and hillsides for the followers of Cargill, Cameron and

Renwick, and the heather was stained with the blood of the martyrs, many an

amiable country gentleman was peacefully attending to the management of his

estates, and had most of his time free for the comparatively arduous pursuit

of his pleasures. One would never suspect, from reading the Account Books of

Sir John Foulis, of Ravelston, that he lived through a time whose tragedies

have stamped themselves so deeply on Scottish memory. The same skies, the

same alternations of rain and sunshine, saw the Covenanters exiled from

human society, upheld through danger and privation by dark sayings of the

Hebrew poets, and stung by their sufferings to an exaltation that was either

prophecy or frenzy; and Foulis, in the friendliest good humour, making

himself popular at horse races and penny weddings, dispensing drink-money to

the midwife, and tossing a hansell with a kind word to "ye muckman that

dights ye close."

Such antitheses could of

course be drawn in our own or any age. Yet the contrasted pictures of the

Covenanter and of the cheerful laird may serve to remind us of the

alternatives that a man had to face when he resolved to stand by the

Covenant, and of the inducement to swallow his qualms and choose the side of

comfort and safety.

In the furnishing of the

times it is possible to trace some reflexion of the events, the changes of

national feeling, and the social contrasts, of which I have reminded you.

Looking back to the previous reign we note that Charles I had been himself

something of a collector and a patron of the arts, and his influence and

example had had their effect in diffusing among the upper classes an

interest in the furnishing of their homes. But with his death and the

establishment of the Commonwealth there was a marked reaction, under Puritan

influence, against ostentation and display, and a general reversion towards

simplicity and even austerity in the whole setting of domestic life. The

eleven years of the Commonwealth were too short a period to bring about any

far-reaching change in the development of furniture, yet all the

characteristic pieces of furniture which we associate with Cromwell's time

are distinguished by their simple design, aiming at usefulness rather than

comfort or ornament. Many of them were of earlier origin, types selected

owing to their being naturally suited to the ascetic views of life and of

human requirements which guided the Puritan's choice. Thus what is known as

the Cromwell chair, a simple rectangular chair with a horizontal panel for

the shoulders to rest on, and with the seat and panel covered with stretched

leather nailed to the frame, was really a development of the "farthingale

chair," the earliest armless form of chair, which was introduced in James

VI's reign to meet the necessity of ladies who found that the enormous

whalebone farthingales, or crinolines, then worn, were a source of

embarrassment when they were given an arm-chair to sit on. In Cromwell's day

the extremely narrow seat of the farthingale chair had been extended to a

more comfortable size, and the legs and stretchers were often turned in a

"knob" pattern, though the straight leg was still perhaps more usual. On

such chairs it was hardly possible to sit otherwise than bolt upright, so

that there was little temptation to idle lounging. In the same way the

gate-legged tables and writing bureaux of the period are furniture of a

plain and homely type, such as men who aimed at sitting lightly to the world

and its vanities might use without danger of having the eye seduced or the

heart entangled.

After eleven years'

experience of Puritan severity and repression, it was inevitable that there

should be a revolt against a system that made little allowance for the

natural instinct for beauty and innocent enjoyment. In Scotland especially,

where the national struggle had never been directed against monarchical

government, but merely against interference with religious liberty, the

restoration of the Stuarts was hailed by most as a return of the good old

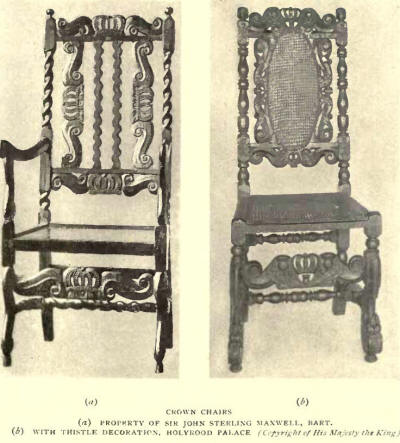

times. Something of these feelings is crystallised in a very familiar type

of contemporary furniture. What is often called a "Queen Mary chair,"

probably because of its association with Holyrood and also, perhaps, because

the crown which is its characteristic decoration somewhat resembles the

initial "M," is typical of the Restoration period. The crown is no merely

conventional piece of decoration, but expressly commemorates the return of

the monarchy; and in days when Royalist sympathies were not only naturally

widespread but were also paraded, and sometimes perhaps even simulated, in

order to allay suspicion of any Covenanting leanings, we need not be

surprised that furniture that testified to one's loyalty had a considerable

vogue. In those days, we are told, a solemn face was apt to prejudice a

man's reputation, and a loud laugh was sedulously cultivated; so that

Royalist furniture, besides being fashionable, had a precautionary value

that appealed to the discreet. One characteristic feature of these chairs is

the carved band which connects the front legs, and here, as on the top of

the chair-back, the crown appears between two S-shaped scrolls or, in more

elaborate examples, between two flying cherubs. The liberation from the

severity of Puritan ideas is shown by the disappearance of straight legs and

stretchers, and the knobbed turning of the late Commonwealth develops into

"barley-sugar" spirals. The back has often a central panel, either

rectangular or oval, which, like the seat, is stretched with trellised cane.

The introduction of cane from the Malay Peninsula about this time was no

doubt due to the East India Company, and Samuel Pepys first mentions it just

after the Restoration, the entry being a rather characteristic one—"This

morning, sending the boy down into the cellar for some beer I followed him

with a cane, and did there beat him for . . . his faults, and his sister

came to me down and begged for him. So I forbore. . . and did talk to Jane

how much I did love the boy for her sake." The early cane seats had a wider

mesh than is now usual, and as they wore out they were often replaced by

padded seats, the backs being similarly treated. Other chairs of this type

have wavy splats in the back instead of cane. Chairs of the same character

are also found in France, but the crown, which had not there the same

significance, is less prominent and appears rather as a conventional

ornament. In English chairs a rose often occurs between the pair of scrolls

which decorates each side of the back panel, while at Holyrood there is a

chair in which the thistle is conspicuously used. In the later patterns we

sometimes find the scroll form of leg—a form imported from France and

destined to develop into the cabriole leg with which we are familiar in

eighteenth-century furniture.

Another piece of furniture

which is decorated with the crown is the day bed, generally called in

Scotland the "resting" or "reposing bed." The day bed, which was the

forerunner of the modern sofa, was known in Elizabethan times, and is,

indeed, mentioned by Shakespeare. It was only after the Restoration,

however, that it came into common domestic use, and it was a considerable

addition to the comfort of the hitherto scantily furnished drawing-rooms of

the time. Like the chairs, these resting beds stood on spiral legs connected

with spiral stretchers, and they had the carved band showing the crown and

scrolls in front. The seat was covered in cane. At one end was a back

intended to support the shoulders, and the inclination of this back could be

varied and fixed by strings to the uprights. The back and the long seat were

furnished with bright-coloured cushions, and altogether the resting bed was

a picturesque and characteristic piece of furniture. It marks, perhaps, the

beginning of the propensity to lounging which inspires so much of our modern

furniture and makes the club smoking-room the paradise of the lethargic

sprawler. The day bed, as a concession to human indolence, was accompanied

by the sleeping-chair, a good example of which may be seen at Holyrood. It

is comfortably upholstered and the back has a projecting wing at each side,

so as to form corners in which it was possible to dose with the head

supported and sheltered from draughts. Notice, as a feature which this chair

shares with the crown and other contemporary types of chair, the carved band

which connects the front legs some way from the ground. As long as rushes

were in use for covering floors, it was practically impossible to keep

floors sweet and clean, and much unsavoury debris of one kind and another

was apt to accumulate. The chairs and tables of those days accordingly show

a plain stretcher near the ground on which the feet could be supported and

kept clear of the floor. But when rushes gave place to carpets or to bare

floors, which are often shown in seventeenth-century prints, the low

stretcher had become an encumbrance which prevented people from tucking

their feet below their chairs if they wished to do so. The stretcher, which

strengthened the chair by binding the front legs together, was therefore

raised, and, being no longer exposed to wear and tear from human heels, it

developed into a decorative feature and was enriched with carving. How

elaborate this carved decoration became may be seen in the double chair,

also at Holyrood, which bears a ducal coronet and a monogram embroidered on

the back of each seat. It appears to date from about 1680.

There are many influences

other than the mere reaction against Puritanism which must be taken into

account in tracing the development of furniture after the Restoration. One

of these is the re-establishment of the Court, which was a powerful factor

in diffusing extravagant habits of living. Charles himself, during his

residence in France and Holland, had become familiar with more luxurious

standards than those that had been countenanced under the Commonwealth ;

and, as Evelyn tells us, "he brought in a politer way of living, which

passed to luxury and intolerable expense." Were it necessary to illustrate

the extent of the reaction at Court against the austere standards of

Puritanism one might quote Evelyn's picture of the Court as he saw it within

a week before the death of Charles II: "I can never forget the inexpressible

luxury and profaneness, gaming and all dissoluteness, and as it were total

forgetfulness of God (it being Sunday evening) which this day sennight I was

witness of ; the King sitting and toying with his concubines, Portsmouth,

Cleveland and Mazarin, etc., a French boy singing love-songs in that

glorious gallery, while about twenty of the great courtiers and other

dissolute persons were at basset round a large table, a bank of at least two

thousand pounds in gold before them; upon which two gentlemen who were with

me made reflections with astonishment. Six days after, was all in the dust."

In much of the furniture of

the period the tendency to ostentatious display is plainly enough shown.

There was a return from Puritan sobriety to the use of rich and brilliant

colours in covering chairs, as well as in cushions and curtains. Some of the

ladies whose names have just been quoted, and others whose names are equally

familiar in connection with the scandals of the Court, exercised a distinct

influence in this direction and had their part in the movement which brought

into fashion all sorts of tinselled fringes, tassels and borders. The same

tendency was shown by the introduction of such materials as ebony,

tortoiseshell, ivory and mother-of-pearl, and their application to coffers

and cabinets and other furniture. Charles had probably some experience of

the use of these eastern substances during his exile in Holland; and they

were brought to England by the English East India Company, which,

incorporated by Queen Elizabeth in 1600, was so prosperous in Charles II's

reign that one shareholder sold out his two hundred and fifty pounds of

stock to the Royal Society for seven hundred and fifty pounds, a transaction

which he describes as "extraordinary advantageous, by the blessing of God."

Some of the furniture with ivory or mother-of-pearl inlay has a distinctly

Saracenic suggestion, and it is likely that this may have come through

Portugal as a result of Charles's marriage with Catherine of Braganca. To

the disappointment of the King, his bride's dowry was paid in kind and not

in cash. It included, besides sugar and spices, a considerable quantity of

furniture which naturally gave a turn to the fashions of the time. The

Braganca "toe" is a familiar type in furniture to this day. Even more

important as an influence than the furniture was the cession to England,

under the marriage treaty, of Tangier and especially of Bombay, which was

the first step towards the acquisition of her eastern imperial possessions.

The exotic materials that

have been mentioned were freely employed in the decoration of the cabinets

which are a feature of the Restoration period. The word was applied not, as

in our time, to large armoires and cupboards, but particularly to

comparatively small chests of coffers supported on stands and containing a

number of drawers. Such pieces were not unknown in the sixteenth century,

and, indeed, Queen Mary had one which is described as "ane cabinet lyke ane

coffer coverit with purpour velvet, quhairin is drawin litil buists to keip

writtingis in." But since Mary's day the habit of writing and the number of

confidential documents had greatly increased. Correspondence must have

reached a considerable volume since the Union of the Crowns. In 1635 Charles

I had inaugurated the inland post "to run night and day between Edinburgh

and London, to go thither and come back again in six days, and to take with

them all such letters as shall be directed to any post town in or near that

road." It was sixty years later before the internal postal communications in

Scotland were taken in hand by the Scottish Parliament. But the amount of

correspondence was enough to explain the demand for cabinets. The religious

diaries too of which we have spoken were presumably kept under lock and key,

for it is one thing for a man to humble himself before his Maker and quite

another thing to tell the story of his lapses and shortcomings to the

peeping Toms, the prying Dicks and the gossiping Harrys of his own

household, to say nothing of their feminine counterparts. Such

considerations and the secrets contained in letters at a time when the whole

kingdom was so divided on questions of religion and politics, and when so

many people for one reason and another changed sides, explain also the

introduction of sliding panels and secret drawers whose use was so highly

developed in the cabinets of the Restoration. Of these the Lennoxlove

Cabinet' is a good type. It is described in an early inventory as "The

Duchess's Cabinet," and it is said to have been presented by Charles II to

Frances Theresa Stuart, Duchess of Lennox, known as "la belle Stuart." The

convex hearts of red tortoise-shell have thus a special significance. If the

outside of the cabinet, with its inlays and applications of various

ornamental materials, is characteristic, so also is the inside with its many

drawers and hidden receptacles. The word "cabinet" means of course a little

house, and it is interesting to note the tradition of architectural

treatment which they exemplify. In this cabinet, as in so many others, the

central recess is flanked by columns, and its floor is inlaid with black and

white squares, like the portico of some great building.

An Act of James VI "Anent

Banqueting and Apparel" had forbidden the use of gold and silver lace on

apparel, "embroydering or any lace or passements upon cloathes, and pearling

or ribbening upon ruffles, sarkes, napkins and sockes." It had even

attempted to perpetuate the "fashion of Cloathes now presently used." But by

Charles II's time such restrictions, as well as those imposed by Puritanism,

had been forgotten, and dress was both gay and elaborate. What with silk

brocades, lace, silver edgings, embroidered belts and all the other fineries

of the day it was found necessary to devise a piece of furniture more

convenient than the old chest or the shelved aurnrie, in which such things

could be kept accessible, free from dust and arranged in some kind of order.

The first step was to add a couple of drawers side by side in the lower part

of the chest; and gradually the number of drawers was increased, till the

hinged lid gave place to a fixed top and the whole of the accommodation was

devoted to drawers. Thus was evolved that modern and convenient piece of

bedroom furniture the "chest of drawers," which is what its name literally

implies, though not in the too literal sense in which an Englishman is said

to have asked in a French shop for a poitrine de cale Eons. The chest in its

original form was now superseded and for practical purposes ceased to be

made. The new form was similar in idea to the cabinets described above, and

in the earlier specimens the drawers, or at least the upper drawers, were

often enclosed by a pair of doors opening in the centre.

Those were days in which a

great deal of liquor was drunk and drink-money was distributed lavishly to

thirsty dependents on all sorts of occasions. But thanks once more to the

East India Company tea and coffee began to come into use in England about

1660, while chocolate was also introduced, and we find allusions to the use

of these beverages in Scotland not many years later. At first they were

looked upon as having a certain medicinal virtue, being recommended for the

"defluxions," but they soon won their way on their merits as beverages and

began to bring about social changes. Tea and coffee houses sprang up, and

there men foregathered to read the news sheets and to play cards and other

games of chance and skill, so that there was soon an increased demand for

small folding tables, often made of walnut—a wood which, being of more even

texture than oak, was a more satisfactory material for the spiral legs

favoured by the taste of the time. The employment of walnut and the

discovery of its special qualities by the workmen who handled it led to the

development of a lighter and more graceful type of furniture than the

cumbrous oak furniture of earlier times, just as the introduction of

mahogany in the following century led to further progress towards the ideal

of slender and sometimes rather flimsy elegance.

The introduction of these

folding tables and of furniture of a comparatively light kind, which could

be easily moved from one part of a room to another, and the gradual adoption

of tea and coffee, and many other small changes of habits, served

cumulatively to bring a more modern atmosphere into the domestic life of the

time. There was also a considerable development of the taste for music in

private houses. Young ladies were taught to play the viol and the virginals,

to the pride of their parents and, let us hope, to the satisfaction of less

partial listeners. The charming pair of virginals shown in Plate XVI is a

good specimen of the instruments on which they performed. It has spiral legs

corresponding to those of the chairs and tables of the time. The keys,

instead of being faced with ivory, are of solid boxwood, which was the

material used for that purpose in Charles II's reign, and they are worn with

the touch of slender fingers which made music two hundred and fifty years

ago. The compass is only about four and a half octaves, and the tone was

sweet and delicate, not powerful and sonorous like our modern pianos with

their massive iron frames and their heavily loaded wires stretched at

enormous tension. At each end of the keyboard is a little carved figure, and

one cannot but feel that this instrument, if less efficient, is at least in

outward form much more charming and sympathetic to the artist than the

French-polished and stony-hearted looking monsters which are its modern

descendants. The fifth, or central, leg seems to be an eighteenth century

addition designed to carry a lever operated by a pedal for the purpose of

opening and closing the lid in order to increase or diminish the volume of

tone. The expression "pair of virginals" does not, of course, denote two

instruments, but merely refers to the series of notes, as in old times a

rosary was called a pair of beads,"or as we still talk of a "pair of

stairs."

One other change contributed

to the modern air of the houses of the period—the introduction of barred

grates in place of the old open fireplace. In the engravings of Abraham

Bosse, who was born about 16io, and whose works are full of interest as

pictures of seventeenth-century life, the fireplaces are open and fitted

with a pair of andirons to support the fuel. The early Scottish grate was

called a chimney, and it was fitted with a pair of "raxis," either standing

or lying ; it had an iron back and at the side there was often fitted a

"gallows" with crooks or chains, from which a pot could be hung. The

customary fireside implements were a "porring irne," or poker, and a pair of

tongs. The "foreface," with ribs, was introduced before 1660, and we read in

Lamont of Newton's Diary in i66 i66i that "The Lady caused make a new

chemnay for the hall of Lundy, of the newest fashion with long bars of iron

before, with a high backe, all of iron behind." Grates of this type may

still be seen in Holyrood, which was restored and furnished for Charles II

in the years following 1671, though those actually in use are reproductions

of the originals still on view.

Before passing on to a sketch

of the social life of the time, let me say a few words on a subject on

which, in my earlier lectures, I have only touched in a negative sense—I

mean the question of the use of forks at table. We have seen that a single

fork was occasionally used for handling fruit, and that the luxurious Parson

of Stobo had one of these rarities in the earlier half of the sixteenth

century. In Coryat's Crudities, published in 1611, the author writes of the

use of forks in cutting meat as a curious custom which he had seen in his

travels, "neither doe I thinke that any other nation of Christendome doth

use it, but only Italy. . . . The reason of this their curiosity is, because

the Italian cannot by any means endure, to have his dish touched with

fingers, seeing all men's fingers are not alike cleane." A character in Ben

Jonson's comedy, The Devil is an Ass, exclaims, "Forks? What be they?" and

receives this answer

The laudable use of forks,

Brought into custom here, as they are in Italy,

To th' sparing o' napkins.

But, though the custom would

thus seem to have been introduced early in the seventeenth century, it

appears to have died out both in England and in France. The explanation may

perhaps be found in the fact that they were found useful at the time when

wide ruffs, worn round the neck, made it difficult to reach the mouth with

the hand; so that when ruffs passed out of fashion the use of forks was

discontinued. In France the practice reappeared among the fashionable and

fastidious in the latter half of the seventeenth century, on the initiative,

it is said, of the Due de Montausier; and a French "Traite de Civilite'

exhorts well-bred persons "porter la viande a la bouche avec sa fourchette."

In spite of this there is abundance of evidence that even in important

French houses food continued to be lifted with the fingers, and it was

apparently only in the eighteenth century that the use of forks was

established as a general practice. Certainly within Stuart times, to which

my own researches have hitherto been confined, I have found no instance of a

supply of forks for table use in Scotland ; and the large numbers of napkins

inventoried in Scottish houses support the view that meat was still handled

as in medioval times. It may, however, be noted that when, in 1669, Charles

II entertained Cosimo II, Duke of Tuscany, knives and forks were laid for

the guests, and there may have been houses where the practice was adopted

before it became a usual one.

A curious point about table

knives may be added. These, as early illustrations show, used to have sharp

points, as penknives still have; and sharp points must have had many

practical advantages. Why, then, have our modern table knives rounded

points? The change took place in France in the first half of the seventeenth

century, when Cardinal Richelieu, disgusted at Chancellor Seguier's gross

habit of picking his teeth with the point of his knife, a habit which was no

doubt common enough, had the points of his table knives rounded to prevent

the recurrence of so offensive a spectacle. The fashion thus set was

generally adopted; and in dissecting the wing of a chicken with a

round-pointed knife one may console oneself with the reflection that one

suffers vicariously for the solecism of a Chancellor of France.

I suppose there is no epoch

of English history of whose social and domestic life we have such brilliant

and intimate glimpses as Pepys' immortal Diary gives us of the period of the

Restoration. In Scotland we have nothing comparable to that sparkling and

outspoken journal. Law's Memorials give many interesting sidelights on the

ecclesiastical and political affairs of the time. Lamont, of Newton, records

with impartial fidelity the meetings of Fifeshire Presbyteries and the

winners of the Cupar horse races. Neither writer has the English diarist's

genius for jotting down vividly and with unflagging zest the trifling yet

enthralling incidents of his daily life. It is only occasionally that such

writers are surprised into an unconventional note, as when Lamont writes,

"Sept. 6, being Saturn's day, the garner's mother in Balcarresse was bitten

through the arme with a puggy ther, which did blood so therafter that it

could not be stem'd. . . . Some few days therafter she dyed." Of all our

diarists of that time Lauder, of Fountainhall, has the most alert

observation and the wittiest tongue. Of a bad crossing to France he writes,

"What a distressed brother I was upon the sea neids not hear be told. . . .

Mr. John Kincead and I strove who should have the bucket first, both being

equally ready. . . . At every gasp he gave he cried God's mercy, as if he

had been to expire immediately." Arrived in France, which he hails as the

land "of graven images," he is "not a little amazed to see upright pod-dock

stools" being prepared for his diet. Of these the Scot partakes without

enthusiasm, yet he owns that "in eating them a man seimes to be just eating

of tender collops." Another experience of French cookery, in which the legs

of a frog were substituted for those of a pullet, drives him to exclaim,

"Such damnd cheats be all the French!" He is far too canny to admit

prematurely any good opinion of those he meets, even if they are fellow

Scots. "The Mr. of Ogilvie and I were very great," he says; but adds, "I

know not what for a man he'el prove, but I have heard him talk wery fat

nonsense whiles." He husbands his expletives to impart a sting to his

observations on men and things which are not of his own country. Thus he

introduces an anecdote of the patron Saint of Ireland with the remark, "The

Irishes hes a damned respect for St. Phatrick." If Lauder's gift of racy

expression had been transferred to Foulis, of Ravelston, and had been

devoted to keeping a journal of his occupations and amusements, we might

have had something like a Scottish Pepys. But Foulis's doings have to be dug

out of his Account Books. There we can trace a round of duties and pleasures

that might have supplied material for a delightful diary; how he went to

Cramond to fish and to Lothianburn to hunt, or how a less cheerful errand

took him to Mr. Strachan, the watchmaker in the Canogait, to have a new

tooth fitted to its place with silk. Leith appears to have been the Elysium

frequented by those who cultivated sport and the drama; to Leith the Laird

of Fountainhall made frequent expeditions to see a horse race or to play a

round of golf; and to Leith he would convey a party to see a comedy—The

Spanish Curate, or The Silent Woman—and would not forget to treat the ladies

during the performance to cherries or oranges. These entries give us a

picture of a cheerful Scottish laird, attending to his estates and the

upkeep of his house, a welcome figure whether in patronising a penny wedding

or in "conveying Lady Kimmergem's corps"; taking in hand the family

shopping, buying a golf club to Archie, Rudiments to Jonie and a pair of

strait sleeves to Lissie, as well as five ells of stringing for "hangers to

hys own breeches"; and at the same time, out of a kind heart and a

comfortable purse, dispensing rather indiscriminate alms to " a poor

irishman, he called himself foulis," "a distrest man named middletoune

wanting ye nose" and other casual applicants; and then, perhaps in doubt as

to the wisdom of his charity, paying an officer fourteen shillings Scots "to

keep away ye poor." If he has many a festive evening and loses many a wager

at golf or cards, he is willing that his family too should amuse themselves,

and he leaves two pounds with his "douchter Jean to give the fidler and play

at cards." Like that hero of song, Captain Wattle, who "was all for love,

and a little for the bottle," he sets small store by literature, science, or

the arts. Public affairs receive little of his attention, though when the

future James VII visited Scotland in pursuit of the anti-Covenanter

measures, he makes it an excuse for another jaunt to Leith, where he hires a

boat "to see the duke of york go abord-o"—the entry having a quasi-nautical

turn which suggests that he enjoyed his day and came home pleasantly

exhilarated.

A good deal of light is

thrown on the social habits of the day in connection with births, marriages

and deaths. On the death of Sir John's first wife, a lad was sent round with

intimations sealed in black to the houses of the neighbouring lairds. The

house at Ravelston was hung with black serge, the church pew was covered

with the same material, and Meg, Lissie and Grissie were provided with black

"under pitticoats." The widower himself requires a yard and a half of black

looping for his hat and hatband, a pair of black shoe-buckles and a mourning

sword, while his horse has to be arrayed in black trappings. The funeral

charges include the "dead chist" and "sear cloathes," the cost of

"embowelling my dear wife," and fees to bellmen, trumpeters and the cryer,

the keepers of the mortcloath, and the herald-painter who provided the

hatchment placed on the front of the house to announce the quality of the

dead lady. Within two months all these bills had been paid, and before

another two months had passed Sir John seems to have forgotten the mother of

his fourteen children and is once more a bridegroom, wearing silver buckles

and garters, paying for an epithalamium and calling once more on the

trumpeters, to play this time at his wedding. Such swift remarriage does not

seem to have been considered disrespectful to the memory of the first wife.

A man, William Lundin, in Fife, married as his second wife Helen Lithell,

and we are told that "the said Helen Lithell was spoken of at the tabell of

Lundin one day att dinner before that the deceaset Elspet Adie, his first

wife, was interred, to be a fitt woman for his second wife." Apparently he

should have waited till a few days after the funeral. Fortunately native

caution prevented many men from running too hastily into matrimony. A

ploughman was asked by the Presbytery of Elgin why he had changed his mind

after proclamation of banns, and gave four good reasons for his having

declined the venture : "1. He could not get his parents' consent. 2. He

could not get his master's consent. 3. The wumman was lous fingered. 4. They

promised him 100 merks and could nor wald pay it."

Among Sir John Foulis's

recreations, billiards is not named, yet it is likely enough that he may

have known the game. Though it is mentioned by Spenser and Shakespeare,

billiards seems only to have been made fashionable by Louis XIV in the

middle of the seventeenth century, and it is all the more remarkable to find

that there was "ane old spoyld bulliert boord" in the West Gallery at Birsay

House, Orkney, so early as 1653. Kirk, who visited Scotland in 1677,

mentions the game as taking up part of his time at Aberdeen. There were, of

course, many on the Crown as well as on the Covenant side who disapproved of

such recreations as billiards, cards and horse racing; and an easygoing

father sometimes incurred severe criticism from his own straitlaced

offspring. It is plain that the Earl of Rothes combined affection for his

daughter the Countess of Haddington with a wholesome dread of her austere

standards of conduct, as the following letter to his son-in-law will show:

"Thursday, wan a cklok.

My Dear Lord,

All that cips runieng horsies in Scotland being jeust going to diner with

me, I have taym onlie to tell you that Sir Andrew Ramsie and Poso runs on

Satirday by aliuin a cklok, which will be a verie gret math, and I beliue

much munie upon it; and on Tyousday bothe the plet runs, at which ther is

six horsies; and Mortein's old hors and mayn runs a by mathe. This is onlie

to inform you, not to inwayt you, for I dear not for my doghter ; but if you

cum, which I wold du if I uere in your pies, you shall be verie velcum to

your

R.

My seruies to my dear Maig,

and all the rest of your good cumpanie.

For the Earle of Haddingtoune—these."

There is one piece of

furniture which is often met with in seventeenth-century houses, whose use

carries us beyond the limits of the house itself. This was the "kirk stuill."

Even "kirk chairs" are mentioned, and these may have been of a folding type

so as to make them easily carried. Usually, however, well-to-do people had

their own pews for which they paid "dask maill" or pew rent, and it was only

necessary to carry with them the cushions, generally covered in velvet,

which gave a certain amount of alleviation while listening to the prolonged

sermons of the time. The use of kirk cushions is mentioned as a new fashion

in the middle of the sixteenth century in Maitland's Satyre on the Town

Ladies, where he says:

In kirk thai are not content

of stuillis

The sermon quhen they sit to heir,

But caryis cuschingis lyike vaine fuillis

And all for newfangilnes of geir.

In the seventeenth century

many of the churches had still thatched roofs, and we read of some in

country districts with "the doors sodded up and no windows." The kirk-brod

or plate, stood at the door, or the collection might be taken by ladles. The

church-goer prepared himself at home by wrapping his intended offering in

his "nepeking end," that is, the corner of his handkerchief, so that he

could lay hands upon it when wanted, and perhaps to prevent his putting in a

coin of higher value by mistake. In some churches the tradesmen sat above in

the pews allotted to the several trades, the gentlemen sat below, and the

women in the "high end" or near the pulpit. When the minister prayed it was

customary for the congregation to "use a hummering kind of lamentation for

their sins," and this moaning and shuddering must have produced a curious

and impressive effect. As to the singing, the custom of "giving out the

line" was introduced about 1640; each line was chanted in monotone before

the congregation sang it. Sometimes the effect of separating the lines in

this way rather perplexed the sense. Thus in the verse beginning:

I'll praise the Lord, and I

will not

Keep silence, but speak out.

the precentor intoned, in all

solemnity, the words, "I'll praise the Lord and I will not," and this

paradox was thereupon adopted unanimously by the loud-voiced congregation.

Taking advantage of their docility the unreasonable precentor went on to

chant, "Keep silence, but speak out!" a command which the faithful flock

echoed without a qualm.

On the pulpit was fixed a

bracket containingan hour glass. As soon as the preacher had given out his

text, the men put on their hats, the glass was turned and the sermon began

and was seldom over before the sands had run out. Sometimes the preacher had

periods of "desertion" in which even men like Thomas Boston "had much ado to

see out the glass"; and sometimes, on the other hand, congregations had to

get their ministers restrained from habitually exceeding the time-limit.

Generally the preachers seem to have taken a gloomy view of the probable

fate of their hearers in the next world. In a Journal of the time we read of

Mr. Rob. Wedderburn addressing his congregation thus: "God will even come

over the hil at the back of the kirk their, and cry wt a by voice, Angel of

the church of Maln (moon) sy, compeir ! Then Ile answer, Lord behold thy

servant, what hes thou to say to him? Then God wil say, 'Wheir are the souls

thou hest won by your ministry heir thir 17 years' Ile no wal what to answer

to this, for Sirs, I cannot promise God one of your souls : yet Ile say,

Behold my own soul and my crooked Bessie's (this was his daughter); and wil

not this be a sad matter?

For the writer of to-day, as

for the preachers of forgotten yesterdays, the sands run low and time

imposes inexorable limits. Were it permissible to view, as Moses did, the

land which I must not enter and to look but a year or two beyond the date to

which I have confined myself, we should find a new Foulis of Ravelston, no

longer wearing his own hair and paying frequent visits to the barber's to

have it trimmed, but decked with a periwig; we should find that James

Peacock has been called in to "cut and powder the bairns' hair," and that

her ladyship is carried to her lodging in a Sedan chair. Such changes

prelude the dawn of the eighteenth century, and, as students of the

seventeenth, we may take a jealous satisfaction in believing that some of

them at least were not endured without a pang. To take to a periwig called

for considerable resolution. With one diarist the crisis of indecision and

procrastination lasted for six months. When he first tried on a wig, he

found that he had no stomach for it, "but that the paines of keeping my

haire clean is so great." Some months passed, and he made another attempt,

but again put it off for a while. More months slipped by, and then, taking

the desperate plunge, he had his hair cut off, "which went a little to my

heart at present to part with it." He adds somewhat ruefully, "But it is

over, and so I perceive after two or three days it will be no great matter."

In our study of Domestic Life

in Scotland we have had to consider many things which in themselves are of

little importance—the setting of a salt-cellar, the lifting of a mouthful of

food, the form of a table or chair. Yet such things are the footprints of

our race on their long journey from primitive barbarism to the usages and

conventions of a humaner civilisation. Step by step man has risen from a

listless tenure of the cave and forest homes which he shared with the

beasts; generation by generation he has wrought for himself a home

reflecting his human desire not only for comfort and decency and order, but

for kindly converse with his fellows, and at last also for beauty and the

exercise and refreshment of the mind. And for us the story of his progress

and the small things and tentative advances of his domestic life can never

be trivial or insignificant.

But on the other hand our

survey, in dealing with the little things and changing fashions of life and

manners, and in recalling the swift succession of eager but transient

generations, may—if we are to seek for a closing morality—fitly enough

remind us also of the littleness of much that preoccupies the minds of men.

If the putting on of a periwig marks and symbolises the end of an era, the

wearer at least mourns the loss of his locks rather than the flight of the

irredeemable years. Though he clings in his heart to old and familiar ways,

the new mode is not to be resisted, and he accepts it with the best grace he

can. Thus is human life tangled in the meshes of worldly mutability. Thus,

amid the vagaries of ephemeral fashion and petty but perpetual change, do

generations pass and epochs roll to their appointed close. Trifles press and

encroach upon us; meanwhile the morning is gone ere we know it, and evening

already draws in. Life, with its romantic offers, comes and swiftly goes,

opportunity flows by and is not to be won again. That fair white page, on

which we had vowed but yesterday to inscribe deeds worth doing and not to be

blotted out, is to-day scribbled and smirched with the record of our

inconstant aims and fitful resolutions. Farewell to all we had hoped for,

had counted on, yet had not the wit to sieze! Little wonder if it goes

somewhat to our heart to part with it. Yet the world goes merrily on. The

virtues we might have won hard in life are freely given us in an epitaph;

and those who follow after us are busy already with the cakes and ale. Of

all our laborious trifling, what remains? Have we added a single stone to

that shining Temple which it is the task of the ages to uprear? Who can say?

The issues of human effort are beyond human disposal. Yet if a man have

learned wisdom, if, losing all things, he have won the grace of a humble

spirit, he may look back at the last on all he had hoped and the little he

has done, and may say without bitterness in his heart, "It is over; and so I

perceive after two or three days it will be no great matter." |