|

OUR survey of the development

of domestic life in Scotland now brings us to the Covenanting period, when

the ecclesiastical differences which had manifested themselves under James

VI became more acute, and the national preference for a Presbyterian system

of church government brought the people into direct conflict with the throne

and began to loosen their tenacious loyalty to the House of Stuart. By his

marriage with the Catholic princess, Henrietta Maria, Charles I forfeited

the confidence of Presbyterian Scotland and exposed himself to much jealous

and suspicious misunderstanding of his conduct and motives. It was his

misfortune that his high conception of his duties and prerogatives as King

was not tempered by something of the watchful caution of his father, and

something of his father's instinct for studying men and waiting for the

opportune moment. Thus the Act of Revocation—involving most of the property

of the pre-Reformation Church, which had been distributed by James VI among

the nobles—drove the nobility to the Presbyterian side, undoing at a blow

what it had cost James much labour and ingenuity to accomplish. The

imposition of Laud's Service Book by authority of King Charles immediately

called forth the National league and Covenant, a protest which was

enthusiastically signed. A year later Sir Edward Verney, writing home from

the English army encamped near Berwick, said, "Wee find all the meaner sort

of men uppon the Scotch Border well inclyned to the King . . . but the

Gentlemen, are all Covenanters."

As soon, however, as the

pacification of Berwick had reinstated Presbyterianism, the Scottish clergy

made the signature of the National Covenant compulsory, thus arrogating to

themselves the right to dictate the national religion—the very right which

they had denied to the King. It was not long before the nobles began to

realise how little their alliance with the Presbyterian ministers was based

on any real harmony of view or congeniality of feeling. It was against all

their traditions to submit to the domination of men whose origin and

upbringing inclined them to look with disfavour on habits, recreations and

indeed the whole scale of social amenity to which the upper classes had

always been accustomed; and it galled them to be dictated to by ministers on

whom they looked down as social inferiors. The result was a revulsion

against the system set up by the Covenant and an inevitable reaction of

Royalist sympathies, and the country was split into two camps—a division

which really arose not from mere class feeling, but from the opposition of

two irreconcilable views of life. For the student of the domestic arts the

evidences of this divergence of view are too plain to be passed by.

Much as Scotland owes to the

Covenanters, for their contribution to Scottish mind and character can

hardly be overestimated, the religion which animated them was of a

singularly austere and forbidding type. Scores of contemporary diaries have

familiarised us with its solitary and introspective character. It was the

fashion of the time to keep a minute record of the individual's religious

experiences, in which were detailed the clouds of doubt and distrust, the

entanglements of temptation and spiritual "discurradgement," the covenants

made, broken and renewed, the darknesses and self-abhorrences, and the

occasional clearnesses, often resulting from the sudden recollection of some

appropriate scriptural text from which the struggling soul "gott some sweete

and comfortabl discoverie" of grace; and then the frequent reaction, when

"Satan began to whisper in my minde, oh I fear this will be lyke the morning

cloud and the earlie dew, that soon passeth away." Even a schoolboy, having

been "intised" into playing games upon the "saboth day," writes, "I fell

into such dread-full terrors that was insupportabl, aprehending it could not

consist with the justice of God but that the earth should open and swallow

me up to hell qwick." It was an unhappy consequence of the current

interpretation of the doctrine of salvation by faith and not by works, that

attention was focussed on states or "frames" of mind, as if these were in

themselves more important than the faithful performance of the allotted

task.

To men of this mould every

natural impulse was apt to appear as a snare of the devil, and every event

of life as merely a phase of the conflict with Apollyon. Even love-making

was no idyllic interlude. Mr. John Livingstone in his Memoirs tells us how a

marriage was "propounded" to him by a third party with the daughter of an

Edinburgh merchant. Propounded! The very word might dissipate the rosiest of

dreams! "I had seen her before several times," he says, "and had heard the

testimony of many of her gracious disposition, yet I was for nine months

seeking, as I could, direction from God about that business; during which

time I did not offer to speak to her, who, I believe, had not heard anything

of the matter, only for want of clearness in my mind, although I was twice

or thrice in the house, and saw her frequently at communions and public

meetings; and it is like I might have been longer in such darkness except

the Lord had presented me an occasion of our conferring together; for in

November, 1634, when I was going to the Friday meeting at Ancrum, I met with

her and some others going thither, and propounded to them by the way to

confer upon a text whereupon I was to preach the day after at Ancrum;

wherein I found her conference so judicious and spiritual that I took that

for some answer to my prayer to have my mind cleared, and blamed myself that

I had not before taken occasion to confer with her. Four or five weeks later

I propounded the matter to her and desired her to think upon it, and after a

week or two I went to her mother's house, and being alone with her, desiring

her answer, I went to prayer, and urged her to pray, which at last she did ;

and in that time I got abundance of clearness that it was the Lord's mind

that I should marry her, and then propounded the matter more fully to her

mother. And although I was fully cleared, I may truly say it was above a

month before I got marriage affection to her, although she was for personal

endowment beyond many of her equals; and I got it not till I had obtained it

by prayer. But thereafter I had a great difficulty to moderate it."

This is one way of love. Let

us not judge too harshly the pious procrastinations of our Covenanting

Romeo. The course of true love never did run smooth. And the story of Mr.

Livingstone's courtship, with its reluctant advances, its palsied

intermissions, and its triumphant and indeed somewhat unbridled close,

serves to remind us once more that "stony limits cannot hold love out."

Keeping before our eyes the romantic picture of the two on their evening

walk to Ancrum, and overhearing in fancy their Doric accents raised in

exegetic heat over the disembowelment of some knotty text—culled, it may be,

from the book of Habakkuk—let us be content to murmur with the poet

How silver sweet sound lovers'

tongues by night,

Like softest music to attendant ears!

And now, by way of

emphasising Mr Livingstone's psychology by contrast, and because it is well

to study the spirit of one century in its development or reaction in the

next, let us compare his narrative with an eighteenth-century letter from a

lady whose affections have been touched. "Mr. Shapely," she writes, "is the

prettiest gentleman about town. He is very tall, but not too tall neither.

He dances like an angel. His mouth is made, I do not know how, but it is the

prettiest that I ever saw in my life. He is always laughing, for he has an

infinite deal of wit. If you did but see how he rolls his stockings! He has

a thousand pretty fancies, and I am sure, if you saw him, you would like

him. He is a very good scholar, and can talk Latin as fast as English. I

wish you could but see him dance! Now you must understand poor Mr. Shapely

has no estate; but how can he help that, you know? And yet my friends are so

unreasonable as to be always teasing me about him because he has no estate.

. . . I forgot to tell you that he has black eyes, and looks upon me now and

then as if he had tears in them. And yet my friends are so unreasonable,

that they would have me be uncivil to him! I have a good portion which they

cannot hinder me of . . . but everyone here is Mr. Shapely's enemy. I desire

therefore you will give me your advice, for I know you are a wise man ; and

if you advise me well, I am resolved to follow it. I heartily wish you could

see him dance, and am, Sir, Your most humble servant, B. D."

This is another way of love.

You will admit that in these two instances the mating instinct operates

somewhat diversely, so that one could hardly have suspected that the

seventeenth-century minister and the eighteenth-century belle were passing

through the same crisis of the affections. Each, perhaps, might with

advantage have learned something of the other. Had the young lady propounded

to Mr. Shapely to confer upon a portion of scripture, with a view to

ascertaining whether his conference was judicious and spiritual, she might

have discovered that that was not the kind of portion that most appealed to

him. And had Mr. John Livingstone, without the long months of painful

propoundings, admitted into his lugubrious bosom so much natural marriage

affection for the lady as to write, "Her mouth is made, I do not know how,

but it is the prettiest that I ever saw in my life," I do not think that

either God or man would have laid it too heavily to his charge.

But I quote Mr. Livingstone's

romance, and contrast it with the engaging foolishness of the later

specimen, because it exemplifies an attitude of mind that was common in

Scotland and elsewhere in the seventeenth century. Mr. Livingstone

represents a generation to whom anything beyond an elementary standard of

domestic comfort was luxury and self-indulgence, and any regard for beauty

and ornament was a concession to the lust of the eye and the pride of life.

Where such views are held we need not look for any development of the

artistic aspect of household life. Like the pilgrims in Bunyan's allegory,

the Covenanters" set very light by all the wares of the merchandisers; they

cared not so much as to look upon them; and if any called upon them to buy,

they would put their fingers in their ears and cry, 'Turn away mine eyes

from beholding vanity.' "

The Puritan spirit, however,

was not the only cause which operated against any general diffusion of

luxury in domestic furnishing. In 1628 Scotland was bankrupt. The nobles,

thanks to the Act of Revocation, had their own troubles. Among the merchants

and tradesmen there were many whose enterprise and industry had amassed

considerable fortunes, but Charles' repeated attempts at legislation against

usury made it difficult for such men to invest their means profitably, and

thus deprived Scottish trade of the capital necessary to its expansion. Yet

progress was by no means arrested. As family life developed, new wants began

to discover themselves; and this and the introduction of new materials and

industries brought about changes which, though small in themselves, had a

gradual and cumulative effect in enriching the setting of domestic life.

About 1620, for instance,

English tanners were brought into Scotland to instruct the native tanners in

"the true and perfect form of tanning." Leather, accordingly, in spite of

the imposition of a special tax, came into increased use for all sorts of

domestic purposes. The inventory of an Edinburgh wright burgess, who died a

few years later, includes a considerable stock of leather backs for chairs,

and of red skins destined no doubt for the same purpose. At Rusco Tower Lady

Lochinvar had "six gilt ledder cuscheounes"; and leather was also used for

the cases in which knives and spoons, brushes and combs, and many other

household goods were enclosed.

Another industry which took

root in Scotland at the same time was glass making. A small glass works was

set going by Sir George Hay in the village of Wemyss, and after some ups and

downs the venture proved successful. A Commission appointed by the Privy

Council examined the glass and reported that it was fully as good as

Danskine glass, though its thickness and toughness still left something to

be desired. A conditional protection against foreign competition was

accordingly granted, and to prevent the native manufacturer from taking

unfair advantage of his monopoly a maximum price for "braid glas," meaning

sheet glass, was fixed at twelve pounds the cradle. Glass had of course been

in use in Scotland long before this. St. Margaret's Chapel, in Edinburgh

Castle, had glass windows in 1336; and, among secular buildings, the palaces

of Linlithgow and Falkland had their windows glazed in the year 1505. By the

time with which we are now dealing every small town had its "glasenwricht"

or glazier. As to glass vessels James IV had a cupboard of these in 1503,

and as we have seen, foreign-made bottles and drinking-glasses had come into

fashion in James VI's time. But it is only after the setting up of the glass

works at Wemyss that we find table glass in common use in ordinary houses,

different shapes being made for wine, beer and other beverages. Foreign

glass of course also remained in use, and Lord Melville had a cupboard of

Venice glass valued at five hundred pounds.

Along with glass we may note

the gradual introduction of earthenware dishes, though whether these were of

native manufacture is not clear. In most houses tin or pewter dishes

continued to be used, while here and there the earlier "tree" or wooden

dishes were still employed. Earthenware dishes had been imported from I-Iolland

by Halyburton in the fifteenth century, but it is not till Charles I's reign

that we find frequent reference to their domestic use. Though subject to

breakage they had the advantage of being cheaper and more easily kept clean

than pewter, and as they are sometimes described as painted their colour

decoration may have been an additional attraction.

Earthenware was also used for

less utilitarian purposes. The tradition which furnishes the cottage

chimney-piece with highly glazed and boldly coloured dogs or human figures

is an ancient one. In 156z there was among the effects of Queen Mary "ane

figure of ane doig" made in white earthenware, and such figures are often

found in Charles I's time. It is startling at first sight to read that Mr.

John Bonyman, dying in 1631, left among other things "thrie lame babies and

three lame doges," but the notion that his house offered hospitality to

cripples of all descriptions may be dismissed. These "babies" were merely

small figures which, like the dogs, were made of "lame," that is loam or

earthenware.

Another influence which must

be taken into account as contributing to progress in house furnishing was

the increasing familiarity with English standards of comfort and elegance.

It had become customary for the well-to-do to send to London for their

furniture. Thus on his daughter's engagement to Lord Cardross, Sir Thomas

Hope, the Lord Advocate, who was an open supporter of the Covenant, made a "nott

of some furnischings to be coft in London and sent home." He estimated the

cost at two hundred pounds sterling, and added, "With Godis grace I sal sie

the samyn thankfullie payit." The so-called furnishings included some "abillzeamentis"

for the bride, for fashions in dress were also set in London. Many a

gentlewoman in Scotland, profoundly distrusting local standards of fashion,

must have had recourse to agonised appeals such as that addressed by one of

their English provincial sisters to a friend in London—"`I pray send me word

if wee bottone petticotes and wastcotes wheare they most be Botend."

That we may have an idea of

the actual arrangements and furnishing of the time, let us examine some of

the principal rooms of the house of a Scottish nobleman who died in 1643.

The house may be taken as fairly typical of its class, and it is interesting

because it illustrates the transition from the lingering mediaeval tradition

to a still immature appreciation of the possibilities of family, as

contrasted with feudal, life.

Of the kitchen we need only

remark that it is on the ground floor, that it is well supplied with brazen

pots and pans and cooking utensils of all kinds, and that there are many

dozen of tin plates, all of which are engraved with the family arms. No

seats of any kind are provided for the servants' use.

We may also pass by the

"Gentlemen's chalmer," only remarking, as to the significance of the name,

that as one writer puts it "our nobility must needs have their menials

gentlemanised," and that the room was occupied by menservants, some of whom

slept in beds and others on shake-downs on the floor. The application of the

word "gentleman" to menservants is not an exclusively Scottish use; but the

English traveller, Christopher Lowther, was struck in 1629 by the fact that

Scottish gentlefolk called their men and maids Misters and Mistresses.

Probably the Scottish tendency to greater formality in forms of address is

one of the traces of early association with France.

The special interest of the

house begins with the "Laiche Hall." In the mediaeval house, as we have

seen, the hall was the principal apartment, and it was always on the first

floor. But now that the family had withdrawn from the hall to the private

Dining-room and Drawing-room, the hall lost its importance and was relegated

by the architects of the time to the ground floor, which was associated by

tradition with the cellars and vaults, while the first floor was reserved

for the more modern sitting-rooms used by the family. The Laiche Hall, thus

banished, still bears some resemblance to the feudal hall of earlier days.

Its walls are covered with hangings, it is furnished with an extending table

surrounded by chairs in place of the older-fashioned board and forms, and

there is a large fireplace in which a hospitable fire might still blaze. But

the hangings are worth comparatively little, the fine arras being reserved

for the rooms upstairs; the chairs are only five in number, showing how

little company the old hall sees in its declining days; and the fireplace is

unfurnished save for a pair of tongs. In a word, the hall has outlived its

purpose and is already half-way towards the cheerless no man's land that it

has become in the modern house.

Above the hall is the modern

room which has supplanted it—the "Dyneing Room." Here are displayed seven

pieces of arras hangings, clothing the walls with rich colour. Instead of

the mediaeval board there are five Spanish tables, besides three others kept

in reserve in another part of the house. These were probably of uniform size

so that any number required might be set in contact to form one continuous

table, either straight or with rectangular extensions. In the room itself

there are seats for as many as twenty-two guests, and this number could of

course be supplemented if necessary. All of these seats were covered with

"carpet," a thick woollen material. Ten of them, having backs, were used for

the more important guests, while the remainder were stools or tabourets. The

windows had striped hangings; there was a long Persian carpet valued at five

hundred merks, and three short carpets which may have been used as

table-covers. At the fireside, which was furnished with shovel and tongs,

stood two vessels for holding coal. These were made of tin and were valued

at one hundred merks.

It will be noticed that

neither in the hall nor in the dining-room is there a cupboard or dresser,

nor any form of buffet or serving-table. Yet in the pantry we shall find

that the silver for the table is what might be looked for in a house of this

character. There are two silver basins and ewers, each set weighing 12lb.

and one of the sets being gilt; two great gilt and chiselled silver cups

with covers; tankards and tumblers of silver; a great silver salt-fatt; two

large silver candlesticks, two dozen silver spoons, and twelve silver

dessert dishes. There is no mention of forks except that there is a case

containing eleven knives followed by an entry of "ane fork." The fact that

the fork was a single one shows that it was used only for serving fruit or

some such special purpose.

The tumblers mentioned in

this list were tumblers in the literal and original sense of the word, for

having no flat base they would not stand upright on the table, but had to be

emptied and turned upside down. They are spoken of by Samuel Pepys some

twenty years later, and his reference to them is the earliest known to the

New English Dictionary.

After the dining-room, and

probably communicating with it, comes the drawing-room, one of the earliest

instances in Scotland of a room called by that name. We are so familiar with

the social uses of the drawing-room in our own day that we can hardly

realise the vagueness with which people in the first half of the seventeenth

century were feeling for a type of room which should answer the scarcely

defined wants of their social life. There was no precedent, no tradition to

give them a lead. The room was one to withdraw to after supper, and in it

the dessert was no doubt eaten; but what were the occupations or amusements

with a view to which the "room was to be furnished? In the mediaeval hall

there had been musicians and sometimes visits from jugglers and other

wandering performers. These, however, belonged to an age that was past, and

the family, thrown on its own resources, had to devise its own methods of

passing the time. In many households this would present no difficulty, but

there are also people who have little initiative in such matters and who

find themselves at a loss unless they are entertained by others. The house

under our notice shows little evidence of any organised family life. The

drawing-room was a room with a fireplace and two turrets. In each of these

turrets, or "studies," as they are called, there was a carpet stool; in the

drawing-room itself there were only a set of eight chairs with padded backs,

covered with blue and red satin damask, and a reposing chair "conforme," or

en suite. There is no table of any kind, though sometimes, perhaps, some of

the Spanish tables in the dining-room may be brought in; no cabinets or

aumries; no musical instruments nor signs of chess, backgammon or cards; no

curtains, blinds nor carpet; still less are there books, or pictures, or

bowls for flowers, or a Block. Besides the handsome set of chairs and couch

there is nothing of any kind whatever save a shovel and tongs by the

fireside, and one other article so strangely out of keeping with modern

ideas of a drawing-room that it must not be ignored—a chamber pot.

From the absence of

comfortable furnishings we see that while the drawing-room had been adopted

as a new and fashionable addition to the family apartments, many a Scottish

family had some difficulty in adapting its habits to the use of such a room.

In the house we are examining "My Lordis bed chamber" was supplied with a "wrytting

standard," and he no doubt preferred to write his letters there. And it is

probable that the comparative novelty of private bedrooms—each with its

separate entrance, instead of opening off one another—through which other

persons did not keep coming and going on their way to their own rooms,

tempted inmates of the house to neglect the new public rooms and the social

life that ought to have united the family there.

Of course ideas of furnishing

and standards of comfort varied very widely even in houses of the same

class. Lord Stormonth, for instance, who died in 1636, had in his house many

of the things we have missed in the cheerless and scantily furnished

drawing-room that has been described. Not only had he portraits on the

walls, but he cultivated music, for there was a pair of organs; and we find

also needlework chairs and embroideries, and chess and backgammon boards. In

which room these were kept, however, we are not told, so we can draw no

inference as to the development of a particular type of room corresponding

to the modern drawing-room.

But however the contents of

Scottish houses were distributed over the various rooms—and early

inventories seldom give this information —there was a distinct advance in

the richness and variety of furnishing and ornaments. In addition to the

Turkey and Persian carpets that have already been mentioned we learn that

China carpets were also known; and as showing the wide geographical range

from which the wants of Scottish homes were supplied, one house in Aberdeen

had Dutch tablecloths, Venice sponges, Indian saucers, Muscovite goblets and

Turkish turbans! This may be an exceptional instance, due perhaps to some

member of the household having followed the sea; but foreign ornaments and

curiosities were by no means uncommon, one favourite ornament being what

were called "Indana nootscheillis"—in other words, coco-nuts, set on a

silver stem and lined, or at least lipped, with silver.

Among the changes which

followed from the abandonment of the hall and the separation of the life of

the family from that of the servants, was the introduction of the domestic

handbell, which now became necessary to summon the servants when they were

wanted. It was not till the opening years of the eighteenth century that it

was superseded by the bell hung in the kitchen and rung by wires from the

various rooms. Another sign of the times was the introduction of the

basin-stand. It was at first used only in the hall or dining-room, in

whichever a particular family might dine, and it went by the name of the "knaiff"

or knave. A young lad had hitherto held the basin in which the principal

persons washed their hands before a meal, but the new tendencies led to his

place being taken by a wooden "standard" or stand, which was accordingly

called after him on the same principle as that on which we call a revolving

table with two or three stages a "dumb waiter," or on which a fireside

candlestick is called a "Carle" or a "peerman" in various parts of Scotland.

These alterations in the domestic arrangements also gave rise to a new

apartment in the architecture of the time, known as the "lettermeitt house."

It was in effect a mess-room for men-at-arms or an upper servants' hall, and

it derived its name from the fact that the joints at the family meals were

removed when done with and served at the later-meat house. Inventories show

that the linen for the lettermeitt house was intermediate in quality between

the linen used by the family and that thought good enough for the kitchen.

The bedrooms of the time

showed a considerable advance on the days when there was often little

furniture beyond the bed or beds, a chest, and sometimes a table and form or

stool; yet they lacked many things which we now count elementary

necessities. The swinging toilet mirror not yet having been introduced, the

dressing-table as we know it did not exist, though in France a draped table

with brushes and shaving materials is shown in one of Abraham Bosse's

engravings, and a framed mirror was often, no doubt, propped up on a table

by the window. More often they were hung upon the wall, or only a hand-glass

was used. Such as they were these mirrors no doubt served the same purpose

that ours do today—to gratify a woman's longing to see that everything is

right, and relieve a man's anxiety to see that nothing is wrong. Nothing

like the modern commodious wardrobe was to be found, and the clothes were

still kept in a chest, in the lower part of which, however, were now

sometimes fitted a couple of "shuttles" or drawers. Neither is there any

washstand, and, indeed, if it was usual to wash in the bedroom at all, which

it probably was not, a basin and ewer must have been brought for the purpose

by a servant. Baths are never mentioned, and when these were taken it was in

a large tub or "baith-fatt," with which, in medieval days, a canopy had been

used to ensure a measure of privacy. Public baths, which played so important

a part in foreign town life in the fifteenth century, and which, it must be

added, generally acquired so doubtful a reputation, do not seem to have

existed in Scotland till early in the second half of the seventeenth

century, when there were "bath stoves" or "sweiting balnes" in Edinburgh.

But, to tell the plain truth,

neither in Scotland nor elsewhere had habits of personal cleanliness yet

come into fashion. It is probably true that, as M. Henri Havard suggests in

his book, L'art et le Confort, the origin of the fashion which led ladies in

the eighteenth century to receive visitors while they performed their

toilette, was an ostentatious pride in the display of standards of

cleanliness which were a reaction against the slovenly neglect that had

hitherto prevailed. Washing, so far from being a habit, was only occasional,

though, as we have seen, the hands were superficially cleansed at meals. A

French writer on manners proposed what was no doubt considered a high

standard when he urged his readers to take the trouble to wash their hands

every day, and their faces "nearly as often"! He added that the head too

should sometimes be washed. This was in Charles I's time, when men as well

as women wore long hair, and the counsel was all the more necessary, if also

all the more troublesome to carry out. It was, in fact, the increasing

desire for cleanliness that eventually led to the adoption of the periwig.

Another advance in manners

was the use of the handkerchief, which however was still by no means

general. Handkerchiefs had been known in the sixteenth century, but Erasmus

enumerates various primitive and unseemly expedients practised by his

contemporaries in attending to what we may delicately call nasal hygiene,

all of which were evidently more usual than the use of the handkerchief.

Another writer some years later, giving rules for elegant deportment in

society, says that if in blowing your nose you use a handkerchief "you will

earn great praise"? One of Abraham Bosse's engravings shows a

seventeenth-century interior in which a lady uses a handkerchief, and in

doing so she turns her head away from the company—a rule of politeness

dating from the days when handkerchiefs were not in use.

The bedrooms, however, were

pleasant enough rooms. In ordinary houses the walls were painted or

whitewashed, the mean if convenient practice of using wall-papers not having

been introduced till after 1800, when "China papers" began to come into

fashion. In more elegantly furnished houses there would be hangings of

camlet or of arras, while occasionally, as in Lady Melville's bedchamber at

Monymaill, the walls were hung with stamped and gilded leather. The

furniture generally consisted of a chair and stools covered with stuff to

match the bed-curtains, and a table covered with the same material. The

whole suite thus made up was considered as going with, and forming part of

the equipment of, the bed. Beyond the chest and mirror already mentioned and

sometimes a shelved aumrie or press, there was little else but the

candlesticks.

The principal piece of

furniture was of course the bed itself, and it may be worth while to cast

back and review the development of beds, and especially of some of the

varieties that were characteristic of Scotland.

George Buchanan, writing of

the hardy habits of the Highlanders, says, "In their houses also they lie

upon the ground, strewing fern or heath upon the floor with the roots

downward, and the leaves turned up." And he adds that they had the greatest

contempt for pillows and blankets. In early times it was very much in this

fashion that the retainers in Scottish castles passed the night in the hall,

making themselves as comfortable as they could on straw or heather, or, as

civilisation advanced, on sacks or rude mattresses filled with flock, and

known as "knop seks." Before the end of the fifteenth century stand beds,

which were beds raised from the floor on "stoups" or legs, were used by all

the more important persons in the household. There were various forms of

stand beds. The "strek" bed seems to have been one in which the mattress was

laid on stretched supports instead of on boards. The "letacamp" or camp bed

(lit de camp), sometimes amusingly perverted into "litigant," was originally

a folding bed suitable for carrying on a journey, and we read in the Lord

High Treasurer's Accounts for 1489 of "tursing (i.e. packing and

transporting) the kingis letacamp bed to Dunbertane." Such beds were often

fitted with a portable canopy, so that the traveller, even if the bed had to

be set up for the night in squalid surroundings, might have his own seemly

hangings round him. When a nobleman with his family and retinue went from

one of his country seats to another, all the necessary furniture, including

tapestries, beds, and sometimes even the windows and doors, was carried with

them. When the Percy family in England travelled there was an order that one

bed must serve for every two priests or gentlemen, and one for every three

children. In Scottish houses the stand beds had a covering of serge, kersey

or arras, and they were fitted with blankets and sheets as well as bolsters

and pillows with the necessary "codware" or pillow covers. The use of a "rufe,"

or canopy, with curtains was very common, but it was suspended from the

ceiling and did not form part of the bed. The four-poster, in which the

canopy is supported on the posts, first appears in the list of beds

belonging to James V in 1539. This is the most important type, and we shall

return to it after describing some other varieties.

The introduction of "kaissit

"beds, in which wooden boarding or panelling took the place of hanging

drapery, is only a phase of the movement which brought panelled walls into

fashion instead of tapestry. Among the "insicht geir" in Dumbarton Castle in

i 58o was a "stand bed of eastland timmer with ruf and pannell of the same,"

the pannel, or pane, being the vertical part rising from behind the pillow

to the back of the canopy. But thirty years earlier Laurence Murray, of

Tullibardine, had left among his effects "twa clois beddis." These were the

characteristic box beds, known also as "buisties" or "boushties," still to

be found in many a cottage. Their use was noted by Fynes Moryson, the

English traveller, who, being in Scotland "upon occasion of businesse" in

1598, thus described them: "Their bedsteads were then like Cubbards in the

wall, with doors to be opened and shut at pleasure so as we climbed up to

our beds. They use but one sheete, open at the sides and top, but close at

the feete, and so doubled." The enclosing of the bed with wooden doors or

sliding panels was the outcome of the contemporary desire for "close" rooms.

Tapestried chambers were too often draughty and uncomfortable and our

forefathers' ambition was to have their rooms air-tight so as to exclude

draughts. The discomforts of closeness, in the modern sense of exhausted and

vitiated air, had still to be discovered, and the early box beds, which

excluded light and air, were no doubt considered in their day the last word

in luxury. Early in the seventeenth century Gordon, of Abergeldie, had "ane

clos kaissit bed, lokkit and bandit" in which we may assume that he slept

secure not only from the intrusions of man, but also from the insidious

encroachments of ventilation. Such beds were often provided with a

bed-staff, which Johnson's Dictionary erroneously defines as "a pin to keep

the clothes from slipping." In Satan's Invisible World Discovered there is a

tale of a ghostly visitant in which this incident is related: "The night

after, it (the apparition) came panting like a dog out of breath; upon which

one took up a bed-staff to knock, which was caught out of her hand and

thrown away." This is the only literary reference to the use of the

bed-staff which I know. No doubt the bed-staff was so used to knock with

when there were no bells to call attendants, but its characteristic use was

in arranging the bedclothes on a bed which was only accessible from one

side—spreading them smooth and tucking them in on the further side. For this

purpose it is still in use in Fife and elsewhere.

Probably the "bureau" bed,

used in the eighteenth century, was a descendant of the box bed. It was made

to fold back during the day on a hinge near the floor into a niche in the

wall.

The white-washed wall, the

nicely sanded floor,

The varnished clock that click'd behind the door;

The chest, contrived a double debt to pay,

A bed by night, a chest of drawers by day.

So Goldsmith describes it,

and in many houses designed by the brothers Adam it was used to economise

space in the servants' quarters.

One other form of bed worth

mentioning is the truckle bed. Truckle beds were employed at Magdalen

College, Oxford, in 1459, but they seem only to have come into use in

Scotland in the sixteenth century. A personal servant was thus enabled to

sleep in his master's room on a bed which by day was run under the standing

bed on which his master slept. In 1566 the "Wyide Chalmer," of Calder House,

had "ane turnit bed with ane draw bed under of plane tre," while in another

room there was what is described as "ane laych rynnand (low running)

bed"—another name for the same thing. It was this arrangement, whereby the

master slept on a higher level than his servant, which misled the Scottish

Laird who, arriving at an English inn with his servant, was given a room

with a four-poster. "Such furniture being new to the Highlanders"—I quote

from an old chapbook —"they mistook the four-posted pavillion for the two

beds, and the Laird mounted the tester while the man occupied the

comfortable lodging below. Finding himself wretchedly cold in the night, the

Laird called to Donald to know how he was accommodated. `Ne'er sae weel a'

my life,' quothe the ghilly. `Ha, man,' exclaimed the Laird, 'if it wasna

for the honour of the thing I could find it in my heart to come doun.'" Such

pretentious furniture was not to be found in Scottish inns, where the

accommodation was of the most primitive kind, and there was, as a Scottish

traveller remarked on returning north of the Tweed, "a sensible decay of

service by that a man has in England." But it must be borne in mind that the

upper classes in Scotland did not make use of the inns, being usually able

to count on the hospitality of persons of their own rank. The inns,

therefore, laying themselves out for a lower class of visitor, did not make

a favourable impression on travellers in Scotland. One complains that "the

bottom of my bed was loose boards, one laid over another, and a thin bed

upon it"; while another speaks of "mean beds where we might have rested had

the mice not randezvoused over our faces."

In private houses, however,

the four-poster soon established itself, and the royal inventories show us

that such beds were richly decorated and must have given an imposing air to

the rooms in which they were placed. One of those belonging to James V was

hung with purple velvet with fringes and tassels of silver; others were

draped in crimson or equally rich colours, while it was not unusual to

employ "variant," or shot silk, whose play of colour must have produced

effects of great splendour. Various kinds of decoration were made use of in

ornamenting the royal beds. Some were "pasmentit," that is, enriched by the

application of gold and silver lace, while needlework and embroidery were

also employed. Thus another of James V's beds had a "rufe with ane heid and

overfrontale of cramosy velvott, with the stone of the life of man upoune

the samune, comparit to a hart, all in raisit wark in gold, silver and

silk." In Queen Mary's time the royal beds were even more elaborate, and in

their decoration embroidery and needlework were carried to a high pitch. One

comparatively plain bed among them is of some historical interest. It is

described as "of violett broun veluot, pasmentit with a pasment made of gold

and silver, furnished with ruif, headpiece and pandis," and it had curtains

of violet damask. It was in this bed, given by the Queen to Darnley in

August, 1566, that Darnley was asleep in his lodging in the Kirk o' Field

when the explosion took place which caused his death. So much violence and

tragedy is covered by the terse note in the inventory "the said bed was tint

in the Kingis ludgeing." Even what are inventoried as" plane beddis not

enrichit with onything "were sometimes rather gay for modern standards of

taste. One, for example, was "of veluot, reid yallow and blew" with "`thrie

curtenis of dames (damask) of the same cullouris unfreinyett " (unfringed)—as

though the shy god of sleep were to be caught lurking in the rainbow!

Among the State Papers

relating to Queen Mary is one (No. 408) dated October, 1587, giving a list

of "Devices on the Queen of Scots Bed." About fifty of these allegorical

devices are described. In the description of them there are several

references to colour. It is possible, of course, that the devices may have

been carved on the wood of the bed, and then heightened with colour and

gilded. But it is much more probable, and quite in accordance with the usage

of the time, that the so-called bed is really a bedcover, probably the same

as that referred to in the inventory of articles left in possession of

"Andrew Melvin, gent " (State Papers, No. 292), and there described as

"Furniture for a bed, wroughte with needle woorke of silke, silver and gold,

with divers devices and armes, not throughlie finished." Many of the devices

and mottoes are philosophical reflections on the fateful circumstances of

Mary's life. One represents "A Lioness and her little cub near to her" with

the motto, "Unum quidem, sed leonem." Another shows "A dove in a cage, and

an eagle above ready to devour her when she shall come forth," with the

motto in Italian, "I am in evil plight, but I fear worse." A third consists

of "Two crowns on earth and one in heaven, composed of stars with flames of

fire issuing from them," and the motto, "Manet ultima coelo."

One characteristic custom of

the time was the use of mourning beds draped in black. The statement is

constantly repeated that mourning was unknown in Scotland till the death of

Queen Magdalen in 1537, the authority of George Buchanan having been

accepted without question. So far as it applies to public mourning the

statement, may be correct. An order subscribed by the King was inserted in

the books of the Edinburgh Town Council in July, 1537 (the date of the

Queen's death), which, without express reference to that event, says, "The

lords understandis that the Kingis grace and all the lieges of his realm hes

instantly ado with blak veluott, satyne, dammes and all sorts of blak clayth

. . ."and goes on to forbid raising the price. But private mourning was worn

long before this. It is mentioned in Dunbar's poem of the "edow," which was

in print by 1508. This lady describes how she goes to the kirk "cled in

cairweeds," talks of her "dule habits," and tells us that her "clokkis thai

are cairful (sorrowful) in colour of sable," and such allusions entitle us

to assume that mourning was by that time a well-established custom. The bed

which appears among the possessions of James V in 1542, and which was hung

in black " dalmes " (damask), was probably so draped in sorrow for the death

of his French bride. At any rate, it was not unusual, as the sixteenth

century went on, for well-to-do families to have a special bed for use in

times of mourning, or at least a complete set of black hangings. The same

practice ruled in England. In the Verney Memoirs (Vol. I, p. 293) Sir Ralph

Verney writes to a relative who has announced the death of her husband, and

suggests lending her "the great black bed and hangings from Claydon" as the

only consolation he can offer; and it seems to have been customary to send

this bed round to any branch of the family which had to go into mourning. In

Queen Mary's inventories we find three such beds, two of velvet and one of

damask, entirely in black, with black silk fringes. In 1594 the Laird of

Caddalis had two of these funereal beds, draped in black velvet with black

taffeta curtains; and when we examine the wearing apparel in his house we

find fresh evidence of a period of mourning. There are black velvet "cornettis,"

which are the well-known head-dresses shaped like two horns, worn by women;

three "blak mwchis of talphetie"; and, most unmistakable of all, "ane braid

craip for the duill." As time went on our forefathers gloried in multiplying

and extending the visible signs of grief. On the death of the Earl of

Haddington, in 1643, his chamber was "hung with mourneing"; and five years

later there were not only a "black cloath" bed, with tester, valance and

curtains, and chair and stool covers to correspond, but also black baize

hangings for the rooms, black covers for the forms and other seats, and

black horse-cloths and liveries. Nothing was left undone to emphasise the

most dismal aspects of death and to aggravate the depressing circumstances

of the bereaved. It is even said that the mistress of Brunston had a

particular alley in her garden which she set aside for walking in during

mourning.

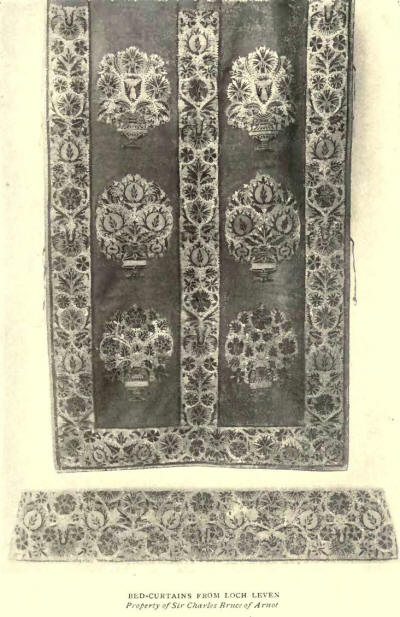

The furnishing of a

four-poster in Queen Mary's time consisted of (1) the covering, or

bed-cover; (2) the headpiece or pane, rising from the head of the bed; (3)

the roof or canopy; (4.) three pands, forming the valance or frieze-like

hanging at the top of the curtains; (5) the curtains; (6) the stoup-covers,

the material fitted round the bedposts, usually wound spirally; and (7) the

underpands or "subbasmont," hanging from the bed to the floor. The top of

the bed was often decorated with "standards of fedderis" at the four

corners, while in 1634 a citizen of Aberdeen had his bed similarly

surmounted with no fewer than six tin crowns! As to curtains, there is a set

at present on view at the Royal Scottish Museum, on loan from Sir Charles

Bruce, of Arnot, which are believed to have been hung on Queen Mary's bed

during her imprisonment at Lochleven. They are certainly of that date and

they have many points of interest. They are of crimson cloth divided by

broad bands of applique velvet embroidered in gold and colours. The curtains

are four in number, besides the valances. When they came to the Museum they

were measured, and it was found that while the height was approximately

uniform—about 6 ft.—the width of the separate pieces was remarkably

different, one being 44 in. wide, one 58 in., one 79 in., and the last as

much as 99 in. Curtains are of course meant to hang with a certain amount of

fullness, so they need not be expected to correspond precisely to the

measurements of the bed. The proper arrangement seems to be this: the 58 in.

one is the head-piece; the shortest of all, that measuring 44 in., hangs

next to the head on the side on which the bed was entered; the 79 in. one

hangs along the whole of the opposite side of the bed; and the 99 in. one

extends from that side along the foot of the bed and up the other side till

it meets the short one, the meeting-place occurring just where it would be

most convenient that there should be an opening for entering and leaving the

bed. When the curtains at the Museum were arranged in this way it was found

that the edges of the curtains at this opening were worn—perhaps by Queen

Mary's own hand as she drew them back to face each new morning of her

capitivity. The curtains show a characteristic feature of the beds of the

time, the strings and "knoppis" for tying the curtains from inside before

going to sleep.

Heraldic ornament was often

applied to beds, either in the form of wood-carving, or executed in

needlework on the valance, head or coverlet. But its appearance in private

houses is rare before the seventeenth century. David Wedderburn, the Dundee

merchant, speaks, in 1622, of "ane lite camp bed with my father and motheris

airmes thairon." Sir Colin Campbell, the eighth Laird of Glenurquhy, who had

a taste for magnificence in furnishing, had one silk bed with red hangings,

"ane pand with rid velvett brouderit with blew silk, with the Laird of

Glenurquhy and his Ladie their names and airmes thairon." And other beds,

one of blue, one "incarnatt," and one of shot green and yellow, similarly

bore the arms of the laird and his lady. The taste of the time seems to have

favoured such bright colours as these, and an inventory of 1622 permits us a

chaste glimpse of Mr. Adam Primrose, a native of Culross, retiring to his

slumbers under the glowing shade of "orang growgrane courtenis." But,

whether as a result of Puritan influence or no, these cheerful hues soon

began to lose favour, and such romantic colour-names as crammasie and

color-de-roy passed out of fashion. In their place we have a number of

unpleasant names like "hair-cullour" and "flesche collor," and depressing

ones like "sadd cullor" and " lead colour"; while there are also names, more

attractive in themselves, which none the less stand for dull and neutral

shades of various kinds, such as "gridaline" (gris de lin), a pinkish grey;

"gingalyne," ginger coloured; and the pretty name "philiamort" (feuille

mort) or dead leaf colour. Such colours taken as representative of the time

convey an impression of an age which has lost much of the gaiety and romance

of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Yet on similar evidence what

judgment would the archaeologists of the future pass on our own time, for if

we may trust the advertisements in to-day's papers the palette of the

twentieth century would appear to be laid in with such mysterious shades as

"nigger, putty, jade, bottle, tango and saxe"? |