|

IF, among the nations of

Europe, Scotland has played but a humble part in the development of design

in furniture, the facts of nature and of history at least supply a simple

explanation. A high standard of domestic comfort is the outcome of a long

experience of national prosperity, and the sure index of a well established

social order. Now it is true that, in intellectual culture, Scotland had

reached even in mediaeval times a level which, considering her scattered

population and her meagre opportunities, is remarkable. But if her

reputation in letters was secure, so alas was her poverty proverbial. "What

could have brought us hither?" asked the French knights who, as Froissart

tells us, had come over in 1385 to march against England; "we have never

known till now what was meant by poverty and hard living!" It would be easy

to collect similar testimonies from those who have left records of their

journeyings in Scotland, but the task would be both dismal and unnecessary.

Some of these writers speak of the Scots with kindliness, some with contempt

; but there is hardly one among them who has not recorded some impression of

the poverty of the country. Some hundreds of years ago it was a current jibe

in France that when the Devil led our Lord into a high mountain and showed

him all the kingdoms of the earth and the glory thereof, he thought it

discreet to make one reservation. He "keipit his meikle thoomb on Scotland."

But besides being a poor

country, Scotland was also a singularly unsettled one. By a misfortune of

geography it was her richest provinces that lay exposed to the devastating

raids from the English border. History too brought her mischances. The long

series of regencies during the minorities of the Jameses gave rise to bitter

jealousies and family feuds among the nobles; and from the consequences of

these factions and the social anarchy they brought in their train, not even

the most peaceable country folk could count themselves secure.

"Sum time," says Lyndsay of

the Mount:

Sum time the realme was reulit

be Regentis,

Sum time lufetenantis, ledaris of the Iaw

Than rang sa mony inobedientis

That few or nane stude of ane other aw;

Oppression did sa lowd hys bugle blaw

That nane durst ride bot into feir of weir

Jok-upon-land that time did mis his meir."

This is no fancy picture. Jok-upon-land,

the decent peasant extorting a precarious living from an unkindly soil, was

but too often a sufferer from the violence of the times. The records of

actions for restoration of "spuilzie" not only tell us of such lawless deeds

done by one noble to another, but they are full of petty and ruthless damage

done to poor people who had little to lose. We read of attacks on richly

furnished houses, and we have but to turn the page to find some poor Jok-upon-land

complaining of "scaitht to his horse," another bent on recovering "auchteen

pence takyn furth of hys purs," and a third claiming a still smaller sum for

"hys wyfis hois and schone"; while the august pages of the Acta Dominorum

Concilii have embalmed for us the memory of "ane callit Cutsy," of whom only

this has come down to us, that in a bitter hour four hundred and thirty

years ago, he, or possibly she, suffered the " wrangous, violent and

maisterful spoliatioun of twa sarkis."

To us these acts of oppression bring this

compensation, that as the law required that the pursuer in an action for

restitution should set forth under oath "the avail and quantitie of the

gudis," we have a series of documents giving details and valuations of

household gear in early times, of which we should otherwise have had but

scanty record. Yet we cannot but realise as we read them, what tragedies of

domestic life they describe, tragedies none the less moving that their scale

is sometimes so pitifully small. They bring home to us that, for rich and

poor alike, life was at the mercy of shocks and dislocations of every kind.

Neither for life nor for property was there any security. And we must

acknowledge that, in conditions so unsettled, it was hardly possible that

there should be any equable and progressive development of the arts of

peace. Even if

conditions had, however, been otherwise more favourable, Scotland would

still have been at a disadvantage in the matter of furniture owing to her

comparative dearth of fine timber. Not that Scotland was the treeless waste

that some would have us believe. There was a fair amount of oak in the

neighbourhood of Inverness, as we know from the early records of that town,

while the forest of Badenoch produced quantities of fir trees. Artillery

wheels for the raid of Norham were made in Melrose wood; timber was got at

the same time from Clydesdale and the wood of Cockpen; while James IV used

to send messengers to the Forest of Tern-way, or Darnaway, in Morayshire, to

"ger fell tymmir" there. We have particulars, too, of timber felled at Luss,

and elsewhere in the neighbourhood of Loch Lomond, in connection with the

King's barge, built at Dumbarton in 1494. Still, the visitor who had passed

through England could not but be struck with the comparative scarcity of

trees in Scotland; and though Nicander Nucius, writing in 1545, states that

the whole island abounds with marshes and well-timbered oak forests, it is

questionable whether his journey actually extended to Scotland. We know

that, as a matter of fact, Scotland depended mainly on her imports of "eastland

burdis" from the Baltic; and it is safe to conclude that Scotland was poorly

supplied with timber, though not to the extent suggested by Sir Anthony

Weldon when he said that "had Christ been betrayed in this country, Judas

had sooner found the grace of repentance than a tree to hang himself on."

But any preliminary survey of the conditions

affecting Scottish domestic life and its equipment would be incomplete and

wholly misleading if it did not look beyond the boundaries of the country

itself. Even in mediaeval times Scotland cannot be considered as existing

"in vacuo," or as insulated from foreign contacts. We must have some idea of

how social conditions in Scotland compared with those ruling elsewhere, and

particularly in those countries with which she had intimate relations ; and

we must know something of the channels through which the influences of

countries with a more highly organised social and domestic life were

conveyed to her. Even in England the standard of domestic comfort was, up to

the end of the fifteenth century, much lower than in the principal countries

on the continent of Europe. Indeed, even fifty years later, the Spaniards

are said to have remarked, "These English have their houses made of sticks

and dirt, but they fare commonly so well as the King." In the last quarter

of the fifteenth century, however, there was a clear advance towards comfort

and elegance in house equipment, and furniture of some artistic pretension

began to be introduced. For guidance in such matters England naturally

looked to France and Flanders, and there was, in fact, little important

furniture in England which was not either of foreign origin or at least of

foreign inspiration. It need hardly be said that Scotland, with her smaller

population, her poorer communities and her ruder material civilisation, was

even more dependent on her contact with foreign countries for an advancing

standard of domestic comfort and artistic seemliness. Fortunately we have,

in the Ledger of Andrew Halyburton, an authoritative document as to Scottish

trade with the Netherlands in the closing years of the fifteenth century.

Halyburton was an enterprising Scottish commission merchant, established at

Middelburg, and doing business also at Bruges, Antwerp and elsewhere; and

his clientele included many leading churchmen and laymen in Scotland, as

well as many of the tradesmen who supplied goods to the Royal Household. An

examination of his Ledger shows that the exports from Scotland consisted

almost entirely of unmanufactured products; a few bales of Scottish cloth

seem to be the only exception. The bulk of the trade is in skins, wool and

fish, and even these do not always arrive in creditable condition. It must

be confessed that the exports give a disappointing picture of the

productiveness and industry of the country, and we have to correct this

impression by reminding ourselves that most of the necessaries and some of

the luxuries for home consumption were produced by native industry.

The imports from Flanders are much more various

and interesting, and they may be examined in more detail because of the

light they throw on the social life of the time. We are struck at once, for

instance, with the large proportion of dress materials, velvets and damasks,

silks and satins, as well as humbler stuffs such as "ryssillis cloth,"

buckram and fustian. At first sight this seems inconsistent with the idea of

Scotland's poverty; but we may recall Pedro de Ayala's contemporaneous

statement that the people of Scotland spent all they had to keep up

appearances, and were as well dressed as it was possible to be in such a

country. It must be kept in mind too that a medioval conception of society

regulated the laws of costume; and the demand for costly materials is to

some extent explained by the fact that they had a definite significance in

announcing the rank and social importance of the wearer.

Next to the trade in dress materials comes that

in groceries, spices and wines, and the variety of these shows a rather more

luxurious standard of living than we might have expected. There was, for

instance, a demand for olives, as well as for figs, almonds, raisins and

dates, and for spices and confections of many kinds; while there are

frequent puncheons of "claret Gascheo" "Mawvyssie" and other wines,

including some from the Rhine. Next may be mentioned the trade in church and

domestic furnishings, a trade which considerably increased in the following

century, but was meanwhile of no great volume. To its details I must return

later. Another interesting import consists of illuminated books, chiefly

porteuses and breviaries, and there are occasional shipments of a ream or

half ream of paper. It will be noticed that in all that has been enumerated

there is little that is not destined for immediate use. If we look for

materials for work to be done in Scotland, we find little beyond madder, for

dyeing; some iron, for smith-work; gunpowder, carts and wheelbarrows for

quarrying and building; white and red lead and vermilion, and gold and

silver foil, probably for decoration of churches and other buildings; and

sewing silks for embroidery.

Now consider for a moment what is implied in the

contrast between the exports from Scotland and the imports from Flanders.

Scotland, as we have seen, exported practically nothing but fish, wool and

skins—fish speared or netted in her lochs and rivers and estuaries; wool

sheared from the sheep on her hillsides and lowland pastures; skins of

animals shot or snared in her mountains or forests. Thus the whole outward

foreign trade of Scotland was based, not on the organised industry of

communities of skilled craftsmen and workers, but on the primeval callings

of the fisherman, the shepherd and the huntsman ! In how different a social

atmosphere such a country must have lived from that of one able to send out

immense quantities of tapestries, carved furniture, vessels of silver and

gold, and fruits, spices and wines, to every part of Europe. We must, of

course, make a fair allowance for the fact that the Netherlands was a

clearing-house for European and extra-European trade. It is something that

Scotland was even importing such artistic and other luxuries as Flanders was

able to supply; and it is at least a tribute to Scottish enterprise that

these imports were brought in Scottish vessels, commanded and manned by

Scotsmen. But it can readily be seen that very little furniture, unless of a

rough and merely serviceable kind, was likely to be made in Scotland, and

that anything appealing to a more sophisticated taste would be introduced

from countries having a more highly developed standard of design and

workmanship. This further lesson may be drawn from the facts we have been

reviewing, that it would be misleading to transfer to Scotland any general

picture of mediaeval life which we may have formed from accounts based on

conditions elsewhere. Such accounts are usually drawn from the literature of

countries with a wealthy and elaborate civilisation; from illuminated

manuscripts, highly coloured fabliaux, and finely wrought interiors by

primitif painters, and they are apt to convey an impression that is

overcharged and, in its total effect, untrue, even of life in those favoured

lands. It would be unreasonable to expect to find in Scotland---a country so

poor, so unsettled and so isolated—any such development of the material

setting of social life as existed in Italy, with her splendid artistic

traditions; in Flanders, with her world-wide commerce ; or in France, with

her natural taste and the luxury of her brilliant court.

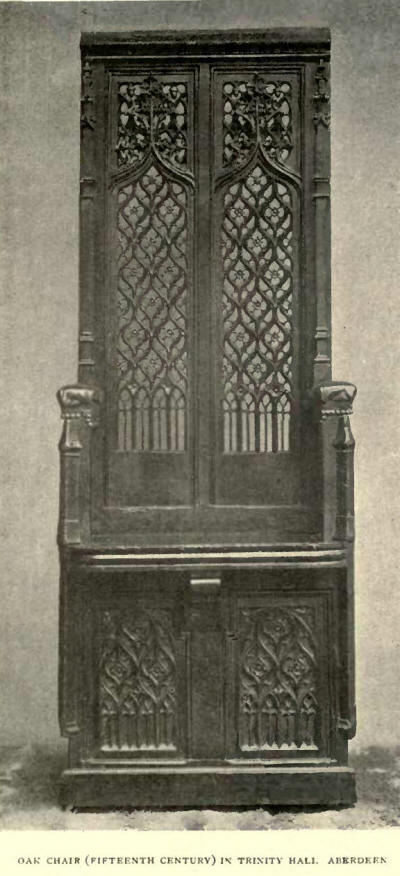

Of Scottish Furniture of the fifteenth century

little or nothing remains; nor have we any contemporary illustration to turn

to for information. But just because, in the absence of such material, the

subject has been neglected, it is worth while to collect such knowledge as

we can derive from literary and documentary sources and to form an idea of

mediaeval practice in house-furnishing, and of the social usages on which it

was founded. Early Scottish poetry is full of allusions to the arrangements

of domestic life, and unless we have some acquaintance with these

arrangements the allusions must remain obscure, instead of casting a homely

light on the poet's thought. It is the more necessary because, while the

medieval tradition persisted during the changes of the sixteenth century, it

disappeared altogether in the beginning of the seventeenth, and the very

words used to describe once-familiar pieces of furniture and traditional

domestic arrangements either acquired a new meaning or dropped completely

out of the language. It was not till two hundred years later, during the

Romantic Revival which originated, I suppose, with Horace Walpole and which

led up to Sir Walter Scott, that there was a movement to recover a knowledge

of medieval customs and to exhume the lost vocabulary. As we shall see, the

editors who at that time reprinted early Scottish poems were often puzzled

by words and allusions which would have been intelligible had they known

more of medieval life, and they were too apt to tamper light-heartedly with

the text, so that they sometimes introduced astonishing anachronisms. Even

the pronunciation of forgotten words was a matter of mere guesswork, and the

word "dais," which we pronounce to-day in two syllables, is an instance of

such ignorance. In early times in this country it was a monosyllable, as it

still is in France.

Let us see, therefore, what was the actual

furnishing of a Scottish Castle in the latter part of the fifteenth century.

Arriving at one of these strongholds in the dusk of a winter afternoon, we

are led up the winding stone staircase by a retainer swinging a horn

lantern. On the first floor is the great hall, an apartment some thirty feet

long, or more, in which the evening meal is about to be served. On one side

a great fire of turf and peat burns in the wide fireplace, where there is,

of course, no barred grate, and casts a ruddy glow through the room. A lad

stands holding a metal basin, and the guests wash in turn, water from a

laver or ewer being poured over their hands by another servant. A long

narrow table is set across one end of the room, and at this the principal

persons, some six or eight in number, take their seats with their backs to

the wall. This table is known as the "hie burde," and it stands on a dais

some inches higher than the rest of the floor, being reserved for the use of

the more important guests. On the wall behind them is a piece of tapestry,

or a simpler hanging of coloured worsted. The lord of the castle sits in a

high-backed chair in the middle, and if he observes great state, there may

be a canopy suspended from the ceiling above his seat. On his right and left

are the guests seated on benches provided with loose cushions, and sometimes

with "bancours" of tapestry or other woven material. The less important

members of the household are seated at side tables, and they too have their

backs to the wall, so that the opposite side of each table is left free for

service from the middle of the room. All those seated at the meal have their

heads covered, the ladies, according to Scottish fashion, wearing kerchiefs

draped from a high structure of real or false hair in the form of two

horns—a dress which the Spanish ambassador described as the handsomest in

the world. Only the servants are uncovered. The reason for wearing hats at

meals seems to have been that it was considered a precaution against the

contamination of the food by what a plain-spoken old writer calls "flyes and

other fylthe." Our present standards of cleanliness and decency were not

reached in a day, and a frank account of some of the table manners of the

fifteenth century would fill us with disgust. Even in France people had, to

be warned that it was bad manners to spit or blow the nose at meals without

turning aside the head ; that one must not struggle to catch fleas at table,

nor seek to relieve the irritation of a then prevalent scalp-disease by

scratching the head.

The table is spread with fair Dornick cloth, a

diapered linen first made at Tournai, the same town which the Dutch called

Dornewyk. Lighted cand1s stand on the tables and there are others in the

chandillars of brass which hang from the roof On the table itself the most

notable object is the salt-fatt, or salt-cellar, often of elaborate design

and considerable size. It had a quasi-ceremonial importance, and servants

were instructed that after the cloth was laid they must first see that the

salt cellar was in place; after that the knives, then the bread, and last of

all the food. The division of the table into "above and below the salt" is

not a medieval one, for those who were socially inferior sat at separate

tables. Pewter dishes were in fairly common use, but even in many important

Scottish houses the old wooden trenchers were not yet displaced. If there

were a shortage of plates, some of the retainers might have to use slices of

bread to hold their food. The spoons were of pewter or occasionally of

silver. Knives are seldom mentioned in early inventories, because it was

customary to use the knives which men carried about with them for general

use. Forks were unknown and food was carried to the mouth by the fingers.

Politeness required that only three fingers, that is two fingers and the

thumb, should be used in handling food; and in drinking, the cup was to be

lifted in the same way. This handling of food, and especially the fact that

it was lifted from the general dish with the fingers, explains the necessity

for the basins and lavers, sometimes of silver, but usually of less costly

metals, which were served for the use of the guests. Towels were provided

and each person had his table napkin. Their use is indicated in a line of

Gavin Douglas's Eneid, where he speaks of "soft serviettis to make their

handis clene"; and how this was done may be inferred from Welldon's

description of James VI, who, he tells us, "rubbed his fingers' ends

slightly with the wet end of a napkin." Well-bred persons of the time were

counselled to avoid gluttony, to eat without suffocating themselves and not

to stare rudely at others eating; they were also to drink moderately,

diluting their wine, and not to suck in their liquor "as if it were an

egg"—meaning, I suppose, audibly —and finally they must not, while drinking,

let their eyes roll about to this side and that.

Looking round the hall, we see that the floor is

covered with rushes or bent grass. A "lyar," or rug, is stretched in front

of the fire, and on it are several cushions serving as footstools. At the

opposite end of the hall from the dais is a rude gallery in which two or

three pipers or fiddlers are exercising their art, and in the corner of the

hall below them are some stands of armour with spears and staves, while a "blawin'

horn" hangs on the wall. There is also on one side of the hall a kind of

service table, not a board detachable from its supports, but a solid table,

such as was called in England a "table dormant." On this any vessels of

silver or pewter that are not in use may be displayed. The only other piece

of furniture is a chest, in which napery is kept and which serves also as a

seat. In the shadow of a deep window we may perhaps discover a

spinning-wheel, and beside it, on a cushion on the stone seat, a "buke of

storeis," its parchment leaves enclosed in boards clasped with silver. On

the wall by the fire-place the light of the flickering candles finds

answering points of reflection in the gilding of a polychrome figure in

carved wood, representing some favourite saint, St. Ninian, perhaps, or St.

Kentigern. Now the

first thing that strikes us in this picture of the hall is how little

furniture it contains. Tables and forms, with a chair for the master of the

house, a side table and a chest, these are all that we find in a large room

where all that is important in the social life of the house takes place. Why

is the hall so scantily furnished? We know that pieces of furniture of many

types were in use—"copamries," "covartur-amries," "mcit-amries,"

"vessel-almeries," "wair-almries" and "wairstalls," besides chests and

coffers of various kinds. Yet these seldom appeared in the hall. Furniture

in Scotland was made for convenience, not for display, to keep dishes and

napery out of the way of dust and accidents, and it was accordingly made

locally of fir or other cheap wood, and consisted of plain, serviceable

pieces with little or no pretension to artistic treatment. On the other

hand, the foreign furniture which was being imported by Halyburton and

others had hardly begun to reach the private houses. The Church, by virtue

of her wealth and her foreign connections, was still the pioneer in

introducing the luxuries of civilisation, and it is to ecclesiastics that

Halyburton sends most of the tapestries and furniture that appear in his

Ledger. It is early in the sixteenth century before we find much Flemish or

French furniture in the houses of the laity. Yet we do find references,

exceptional rather than typical, to the "lang-sadyll" or settle, the "lettron"

or reading desk, and to Flanderis kists and counters, pieces of furniture

such as Halyburton was importing. Goods of foreign origin which were much

more widely diffused were silver salt-fatts and other vessels, brazen

chandillars and candlesticks, feather-beds, pillows and cushions, and, of

course, napery. One entry in Halyburton's Ledger may be specially

mentioned—a reference to an "oralag" sent by Bishop Elphinston for repair,

and returned "mended, and the cais new." This shows that clocks were already

in use in Scotland for ecclesiastical and public buildings, if not yet for

domestic purposes. Let

us examine in rather more detail some of the furnishings and arrangements of

the hall. The dining tables were merely long boards, of oak or fir,

supported by a pair of trestles which-were generally of fir, and when not in

use the board was laid against the wall and the trestles were cleared away.

There was no feeling that the room looked "unfurnished" without its tables.

In the Freiris of Berwik we read how a "hostillar's" wife entertains a friar

in her husband's absence. When the husband unexpectedly returns, she orders

her maiden, according to Sibbald's version (1802), which professes to take

no liberties with the text, to "clear the board." But if we turn to the

Bannatyne MS., we find it is "Close yon board," a much more characteristic

touch, implying that the table itself is to be dismounted and removed.

Go, clois yon burd, and tak awa the chyre

And lok up all into yone almery,

Baith met and drink with wyne and aill put by.

The reference to the single chair, which was the

rightful seat of the master of the house, and to the use of the almery, are

worth noting. We also read, earlier in the poem, that

The burde scho cuverit with clath of costly

greyne,

Hir napry aboif wes woundir weill besene,

and early inventories show that table covers

were, like the cloth of a modern billiard table, always green, a special

cloth known as "Inglis green " being imported from England for the purpose.

The principal table, or "hie burde," set on the

dais and having behind it the tapestry or other wall-hanging, was, as I have

said, reserved for persons of importance, and the dais thus gave a line of

social distinction. The author of Schir Penny, satirising the deference paid

to wealth, in the person of Sir Penny, says:

"That Syre is set on heich deiss

And servit with mony rich meiss

At the hie burde." Some

years ago a paper was read before a learned Society giving an account of an

interesting sixteenth century inventory. The author, an experienced

archa?ologist, had little knowledge of the social uses of the time, and the

result was an extraordinary series of blunders. The first thing mentioned in

the hall was "ane desbuyrd," meaning of course the table on the dais, and

this was interpreted as "a dish-board, or perhaps a plate-rack." The author

then pointed out the remarkable absence of chairs, mentioning that only one

was specified, and that it stood in the hall, which, he said, "indicates a

meagreness of plenishing not easily reconcilable even with the plain living

of the times." The single chair, placed in the hall for the master's use,

was the invariable rule at the period of which he wrote, and chairs did not

come into ordinary domestic use till the seventeenth century. The author of

the paper also interpreted "treying copes" as trying cups, which he thought

might mean measuring cups, whereas they are simply "tree-en" cups, or cups

made of wood; and a "wairstall," a kind of press, he converted into a night

stool, a brilliant effort of fancy! Most of these mistakes arise not merely

from ignorance of the terminology of house furniture of the time, but from

failing to realise the difference between the domestic arrangements and

social life of that age and those of our own day. Early furniture owes much

of its interest to its reflecting customs with which we are no longer

familiar, and it is meaningless unless we interpret it in terms of the

social habits which produced it.

In Henryson's poem, The Twa Mice, we read how

the cat catches one of the mice, and how, in playing with her victim:

Quhyll wad she let her ryn under tthe strae

—the straw with which the floor was covered. The

mouse manages to escape, and Sibbald's version (18oz) tells us that she

crept "between the dressour and the wall " and climbed "behind the

panelling." Now the words "dressour" and "panelling" were not in use in

Scotland when the poem was written, and their introduction is but another

instance of the propensity to substitute for unfamiliar expressions others

more easily understood and perhaps considered more picturesque. When we

consult the early text we find that the mouse escapes, not between the

dressour and the wall, but between "ane burde and the wall," and climbs, not

behind the panelling, but behind "ane parelling," which was the usual name

for the hanging on the wall behind the dais table. The burde, taken from its

trestles, had no doubt been laid along the foot of the wall, and the mouse,

getting behind it, crept beneath the parelling and worked her way into a

position of safety. Accordingly she says, later in the poem:

I thank yone courtyne and yone perpall wall

For my defence now fra ane crewel heist,

the perpall wall being the partition wall on

which the courtyne or parelling hung.

A very interesting and characteristic piece of

furniture in the Scottish medieval hall was the Comptour, or Counter. Few

houses in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries were without one, yet to-day

there are the most conflicting ideas as to what the counter really was, and

what part it played in the domestic life of the time. It has been defined as

a table, a cabinet, a desk and so on, while one reference in an old protocol

book has been held to prove that it was a penannular, or C-shaped, sofa. Let

us see what we can learn from documents of the time when the counter was in

everyday use. But we must bear in mind that in any investigation into early

furniture and its nomenclature we are dealing with names which, though

stereotyped themselves, are applied to furniture forms which are constantly

being modified and transformed in the attempt to adapt them to the varying

uses of a rapidly developing social system. Especially is this true of

pieces of furniture whose use is not limited by having to meet some definite

and permanent human need. Beds, dining-tables and chairs, for example, are

controlled by a certain fixed basis of human requirement; and, under all

their superficial varieties of form, their essential shape and measurements

must have a certain relation to the scale and movements of the human figure.

But when furniture is not so closely bound by elementary needs, the form

remains comparatively indeterminate, and may vary in any direction according

to the wants of those for whom it is made. Thus a name may persist long

after it has ceased to be a correct description of the thing. A Cupboard,

for instance—originally a table for displaying cups —has so changed its use

and form that it has now nothing to do with cups, it is not a table, and it

is used rather for concealment than display:. A Gardevyand, originally

intended, as its name implies, for storing food, developed into a sort of

portable strong box, so that we read of locks and "braycis " being added to

the King's "cardiviance" in order to "twrss west" the gold and silver

vessels of James IV "again Yule to Lythgow." In the same way we read of a "meit-almery

for conserving napery" and a "capamre" (or cup-almrie) for holding clothes.

Thus the name of a piece of furniture must not be taken as indicating

anything more than its original use.

The counter, compter-buird or compt burde, was

originally a table whose top was used as a reckoning board, being marked out

into spaces with distinguishing symbols. It was used for such purposes as

adding up accounts, and for these calculations disc-shaped counters or

jet-tons were employed. When not in use the jettons were kept in metal

cylindrical cases, referred to in Halyburton's Ledger as "nests of countaris."

A reference to the use of the compter burde for calculating occurs in

Calderwood's History of the Kirk of Scotland, where we are told, as one

incident of an earthquake in 1597, that "a man in St. Johnston, laying

compts with his compters, the compts lap off the buird; the man's thighs

trembled, and," adds the faithful historian, "ane leg went up and the other

doun." Counter boards were tables of convenient size and they were built on

fixed legs, not simply laid on trestles. When we bear in mind that these

tables, which were originally imported from Flanders, were the only tables

known except the cumbrous long boards and trestles used for meals, we need

not be surprised that they soon came into common use even among those who

had little need for arithmetical calculation, but who appreciated the

usefulness of a steady, moderate-sized table for many domestic purposes.

Early inventories show that in a large number of houses there was no table

but the counter; sometimes "ane comptar with the furmes" is mentioned,

clearly showing that it was used for the household meals. Medioval

illustration proves that the reckoning board was sometimes provided on the

table-cloth, and this would enable the table itself to be without special

marking and so to lose its arithmetical associations.

There is documentary evidence that as the

counter developed as a piece of furniture it was made with some enclosed

accommodation below. Thus Sir David Lyndsay, of the Mount, left among his

furnishings "ane lokit comptar burde," and we find in the second half of the

sixteenth century an increasing number of references to the locks and keys

of counters, implying that they had closed receptacles. As time went on the

enclosed accommodation seems to have extended downwards till it became the

characteristic feature of the counter, and what had been the surface of the

table now shrank in importance till it was merely the top of a small

rectangular almerie. In the seventeenth century we read of

"counter-almries"; and in the list issued in 1612 of foreign goods subject

to duty on import to Scotland, we find a fixed rate levied on "cabinettis or

countaris." Thus the counter, which, under the name of "ane stop-compter,"

had been used for the display of stoups or vessels as early as 1489, had

gone through a similar course of development to that of the cupboard in

England. The counter, as an article of domestic furniture, seems to have

gone out of use, or at least to have been superseded by other forms of table

and cupboard, about the middle of the seventeenth century. It was retained,

however, among merchants and tradesmen as a useful piece of business

furniture, and the shop and bank counters of our day are thus survivals or

developments of a forgotten medieval form.

In connection with the vessels which stood upon

the counter when it was used as a side table, one interesting question

arises. What is meant by the "compterfute weschel" which often appears in

early lists of household goods? In an English inventory of 1487, quoted as

an appendix to the Paston Letters, we read of "ij garnysshe" (i.e. two

complete sets) "of pewter vessel counterfete"; and, according to an

inventory of 1598, transcribed in the Black Book of: Taymouth, there were

"off counterfute plaittis in the galarie garderob of Balloch, iiij dosane."

These are the only references I have found to counterfute dishes in the

plural, and in these cases it is probable that a counterfeit metal is

intended, though it is hard to say what is meant by pewter counterfeit. The

dictionaries interpret "compterfute" in the sense of "imitation," an

inferior metal meant to imitate one more valuable, and they give no

alternative definition. As a matter of fact the base metal made to resemble

gold was commonly called "alchemy."

But the references in early Scottish inventories

are nearly always to "ane compterfute vessel," or simply "ane comptarfut,"

in the singular, and when this is mentioned as one particular vessel among

others whose character or use is stated, it is difficult to resist the

con-elusion that the name was applied to a vessel serving a specific purpose

or occupying a particular place. This impression is confirmed when we find

the counterfoot grouped with vessels which were certainly silver; and any

lingering uncertainty disappears when we read, in a carefully detailed

inventory of 1542, of a counterfoot expressly stated to be of silver, its

weight being given and worked out at the value of silver per ounce. What a "comptarfut"

was must remain a matter of conjecture till some literary reference is found

which throws light on the problem. The word might conceivably be applied to

a vessel cast in two halves; or, as an alternative suggestion, it might be

used of a vessel which stood at the foot of, or underneath, the

counter—perhaps on a tray contained between the stretchers near the ground,

just as we see vessels displayed in this position in early illustrations of

similar pieces of furniture in other countries, such as credences and

dressers. Let us pass

from the Hall to another room which is often mentioned in documents as to

old Scottish houses, the "Chalmer of Des." The name has, like other medioval

terms, dropped out of use ; I do not think it is mentioned in McGibbon and

Ross, and its meaning has puzzled antiquarians and lexicographers. Jamieson,

discussing the corruption "chambradeeze," properly dismisses the suggestion

that it stood for "la chambre ou ils disent," and tells us that the word was

still in use among old people in Fife for a parlour, and that the original

form was "Chamber of Dais." Sir Walter Scott said it was still common in his

day in the South of Scotland, and was applied to the best sleeping room; and

he suggested that it was the room in which there was a bed with a dais, or

canopy. But the term originated in castles where there were many beds with

canopies, but only one Chamber of Dais; and, moreover, in Scottish records

the word dais is applied to the raised platform, and not, as in France, to

the canopy, which is called the "cannabie" or "rufe," or sometimes, in

connection with beds, the "sparwort." A study of early inventories leaves

little doubt that the Chamber of Dais was the private apartment which so

often communicated with the upper or dais end of the hall. It was the

bedchamber of the master of the house, and it was also used, in accordance

with medimval custom, as a retiring room for those who sat at the dais

table. Those who sat there represented what is called "the quality," and the

chamber was for their exclusive use. Its position and use are clearly shown

by an extract from an old protocol book, which tells us that Peter Rankin,

the heir of Shield, "entered the hall of Scheld and the chalmer of des

within the hall" (meaning that to reach it he had to go through the hall).

After describing the furniture which he found in the hall it goes on, "and

in the chalmer of des he found twa fedder beddis with necessaries, and a

wooden press." It is evident that the Chamber of Dais was in effect the

principal bedroom. I

have spoken of the bareness of the hall in the matter of furniture, but the

furnishing of the bedrooms was equally meagre, and this simply because of

the primitive standard of comfort of the times. Even in an English house so

richly furnished as Arundel Castle, the furnishing of the King's Chamber, so

late as the year 1580, consisted only of a bed, a table and a chair, besides

the tapestry hangings. We need not expect to find a more luxurious standard

in Scotland. In the well-equipped house of Lord Lindsay of Byres—a house

which had its own private chapel with suitable vestments and a gilded

chalice—the Chalmer of Des had no furniture but the bed and "an aid compter,"

on which stood a candle and two books. In nearly all the other bedrooms of

the house there was nothing but the bed or beds, for it was common to put

several beds in one room. Occasionally there is a chest to hold clothes, or

a form or stool, but nothing else was considered necessary. The bed,

however, was often fitted with a "futegang," corresponding to the French "narchepied"—the

long step or stool which we see in medieval illustrations placed along the

side of the bed. The "futegang" was sometimes "bandit," that is, hinged, so

that the top could be opened and the inside used for keeping clothes, and in

this form it is sometimes called a "buncar."

We need not concern ourselves with kitchen

furniture nor with the equipment of the brew-house and bakehouse which were

found in every medieval mansion. If what has been said conveys the

impression that life in a Scottish medieval castle must have been a stern

and comfortless existence, remember that a hardy race is not reared in

luxury. Cast your minds back to the Scotland of that day, set far from the

centres of medieval culture, hard pressed to hold her own against her richer

and more powerful neighbour; a land of mountain and moor, shrouded with

mist, drenched with rain, visited with short and fitful summers and long and

bitter winters, and predestined to a history of jealous factions and

relentless feuds; and remember that in this land was reared a race

hard-headed, resolute and tenacious, yet ever quick to shed its blood for a

great cause, a dear name or a fine point of doctrine; a race ready to go

forth to other lands, however distant and however inhospitable, in quest of

profit or adventure; yet with hearts that kept turning always homeward with

something of the passion which a man cherishes for the mother who has borne

him in pain and nurtured him in poverty. |