|

THOUGH burning with stifled

passions, Earl de Valence accepted the invitation of Lady Mar. He hoped to

see Helen; to gain her ear for a few minutes; and above all, to find some

opportunity, during the entertainment, of taking his meditated revenge on

Wallace. The dagger seemed the surest way; for, could he render the blow

effectual, he should not only destroy the rival of his wishes, but, by

ridding his monarch of a powerful foe, deserve every honour at the royal

hands. Love and ambition again swelled his breast; and with recovered

spirits, and a glow on his countenance, which reawakened hope had planted

there, he accompanied De Warenne to the palace.

The hall for the feast was

arrayed with feudal grandeur. The seats at the table spread for the

knights of both countries, were covered with highly-wrought stuffs; while

the emblazoned banners, and other armorial trophies of the nobles, being

hung aloft according to the degree of the owner, each knight saw his

precedence, and where to take his place. The most costly meats, with the

royally attired peacock, served up in silver and gold dishes; and wine of

the rarest quality, sparkled on the board. During the repast, two choice

minstrels were seated in the gallery above, to sing the friendship of King

Alfred of England, with Gregory the Great of Caledonia. The squires, and

other military attendants of the nobles present, were placed at tables in

the lower part of the hall, and served with courteous hospitality.

Resentful, alike at his

captivity, and thwarted passion, De Valence had hitherto refused to show

himself beyond the ramparts of the citadel; he was therefore surprised, on

entering the hall of Snawdoun with De Warenne, to see such regal

pomp; and at the command of the woman, who had so lately been his prisoner

at Dumbarton; and whom (because she resembled an English lady who had rejected

him) he had treated with the most rigorous contempt. Forgetting these

indignities, in the pride of displaying her present consequence, Lady Mar

came forward to receive her illustrious guests. Her dress corresponded

with the magnificence of the banquet; a robe of cloth of Baudkins,

enriched, while it displayed the beauties of her person; her wimple blazed

with jewels, and a superb carkanet, emitted its various rays from her

bosom.

[Cloth of

Baudkins was one of the richest stuffs worn in the thirteenth

century. It is said to have been composed of silk intenwoven with gold.

According to Du Cangs, it derived its name from Baldack, the

modern appellation for Babylon. or rather Bagdat, where it

was first manufactured. Wimple was a head-dress of the times; it

resembled a veil, not worn flowing, but in curious folds upon the head.

The carkanet was a large broad necklace of precious stones of all

colours, set in various shapes, and fastened by gold links into each

other.—(1809.)]

De Warenne followed her

with his eyes, as she moved from him. With an unconscious sigh, he

whispered De Valence, "What a land

is this, where all the women are fair, and the men all brave!"

"I wish that it, and

all its men and women were in perdition !" returned De Valence in a

fierce tone. Lady Ruthven, entering with the wives and daughters of the

neighbouring chieftains, checked the further expression of his wrath; and

his eyes sought amongst them, but in vain, for Helen.

The chieftains of the

Scottish army, with the lords Buchan and March, were assembled around the

Countess, at the moment a shout from the populace without, announced the

arrival of the Regent. His noble figure was now disencumbered of armour;

and with no more sumptuous garb, than the simple plaid of his country, he

appeared effulgent, in manly beauty, and the glory of his recent deeds. De

Valence frowned heavily, as he looked on him; and thanked his fortunate

stars, that Helen was absent, from sharing the admiration which seemed to

animate every breast. The eyes of Lady Mar, at once told the impassioned

De Valence, too well read in the like expressions, what were her

sentiments towards the young Regent; and the blushes, and eager civilities

of the ladies around, displayed how much they were struck with the now

fully discerned and unequalled graces of his person. Lady Mar forgot all

in him. And indeed so much did he seem the idol of every heart, that from

the two venerable lords of Loch-awe and Bothwell, to the youngest man in

company, all ears hung on his words, all eyes upon his countenance.

The entertainment was

conducted with every regard to that chivalric courtesy, which a noble

conqueror always pays to the vanquished. Indeed, from the wit and

pleasantry which passed from the pposite sides of the tables, and in which

the ever gay Murray was the leader, it rather appeared a convivial meeting

of friends, than an assemblage of mortal foes. During the banquet, the

bards sung legends of the Scottish worthies, who had brought honour to

their nation in days of old; and as the board was cleared, they struck at

once into a full chorus. Wallace caught the sound of his own name,

accompanied with epithets of extravagant praise; he rose hastily from his

chair, and with his hand motioned them to cease. They obeyed; but Lady Mar

remonstrating with him, he smilingly said, it was an ill omen to sing a

warrior’s actions till he were incapable of performing more; and

therefore he begged she would excuse him from hearkening to his.

"Then let us change

their strains to a dance," replied the Countess.

"A ball! a ball!"

exclaimed Murray, springing from his seat, delighted with the proposal.

"I have no

objection," answered Wallace; and putting the hand she presented to

him, into that of Lord de Warenne; he added, "I am not of a

sufficiently gay temperament, to grace the change; but this Earl may not

have the same reason for declining so fair a challenge!"

Lady Mar coloured with

mortification; for she had thought, that Wallace would not venture to

refuse, before so many; but following the impulse of De Warenne’s arm,

she proceeded to the other end of the hall; where, by Murray’s quick

arrangement, the younger lords of both countries had already singled out

ladies, and were marshalled for the dance.

As the hours moved on, the

spirits of Wallace subsided from their usual cheering tone, into a sadness

which he thought might be noticed; and wishing to escape observation, (for

he could not explain to those gay ones, why scenes like these ever made

him sorrowful,) and wbispering to Mar, that he would go for an hour to

visit Montgomery, he

withdrew, unnoticed by all but his watchful enemy.

De Valence, who hovered

about his steps, had heard him inquire of Lady Ruthven, why Helen was not

present. He was within hearing of this whisper also, and, with a Satanic

joy, the dagger shook in his hand. He knew that Wallace had many a

solitary place to pass, between Snawdoun and the citadel; and the company

being too pleasantly absorbed, to mark who entered or disappeared, he took

an opportunity, and stole out after him.

But, for once, the

impetuous fury of hatred, met a temporary disappointment. While De Valence

was cowering like a thief under the eaves of the houses, and prowling

along the lonely paths, to the citadel; while he started at every noise,

as if it came to apprehend him for his meditated deed; or rushed forward

at the sight of any solitary passenger, whom his eager vengeance almost

mistook for Wallace; Wallace, himself, had taken a different track.

As he walked through the

illuminated archways, which led from the hall, he perceived a darkened

passage. Hoping, by that avenue, to quit the palace unobserved, be

immediately struck into it; for he was aware, that should he go the usual

way, the crowd at the gate would recognise him, and be could not escape

their acclamations. He followed the passage for a considerable time, and

at last was stopped by a door. It yielded

to his hand, and he found himself at the entrance of a large building. He

advanced; and passing a high screen of carved oak; by a dim light, which

gleamed from waxen tapers on the altar, he perceived it to be the chapel.

"A happy transition," said

he to himself, "from the jubilant scene I have now left; from the

grievous scenes I have lately shared !—Here, gracious God," thought

he, "may I, unseen by any other eye, pour out my heart to thee. And

here, before thy footstool, will I declare in thanksgiving for, thy

mercies; and, with my tears, wash from my soul, the blood I have been

compelled to shed !"

While advancing towards the altar,

he was startled by a voice, proceeding from the quarter whither he was

going, and with low and gently-breathed fervour, uttering these words

:—"Defend him, Heavenly Father! Defend him, day and night, from the

devices of this wicked man: and, above all, during these hours of revelry

and confidence, guard his unshielded breast from treachery and

death." The voice faltered, and added with greater agitation,

"Ah, unhappy me, that I should be the cause of danger to the hope of

Scotland; that, I should pluck peril on the head of William Wallace!"

A figure, which had been hidden by the rails of the altar, with these

words rose, and stretching forth her clasped hands, exclaimed, "But

Thou, who knowest I had no blame in this, wilt not afflict me by this

danger! Thou wilt deliver him, O God, out of the hand of this cruel

foe!"

Wallace was not more

astonished, at hearing that some one, in whom he reposed, was his secret

enemy; than at seeing Lady Helen in that place, at that hour, and

addressing Heaven for him. There was something so celestial in the maid,

as she stood in her white robes, true emblems of her own innocence, before

the divine footstool; that, although her prayers were delivered with a

pathos, which told they sprang from a heart more than commonly interested

in their object; yet every word and look breathed so eloquently, the

virgin purity of her soul, the hallowed purpose of her petitions; that

Wallace, drawn by the sympathy, with which kindred virtues ever attract

spirit to spirit, did not hesitate to discover himself. He stepped from

the shadow, which involved him. The pale light of the tapers, shone upon

his, advancing figure. Helen’s eyes fell upon him, as she turned round

she was transfixed, and silent. He moved

forward. "Lady Helen," said he, in a respectful, and even tender

voice. At the sound, a fearful rushing of shame, seemed to overwhelm her

faculties; for she knew not how long he might have been in the church, and

that he had not heard her beseech Heaven, to make him less the object of

her thoughts. She sunk on her knees beside the altar, and covered her face

with her hands.

The action, the confusion,

might have betrayed her secret to Wallace. But he only thought of her

pious invocations for his safety; he only remembered, that it was she who

had given a holy grave to the only Woman he could ever love: and, full of

gratitude, as a pilgrim would approach a saint, he drew near to her.

"Holiest of earthly maids," said he, kneeling down beside her;

"in this lonely hour, in the sacred presence of Almighty Purity,

receive my soul’s thanks for the prayers I have this moment heard you

breathe for me! They are more precious to me, Lady Helen, than the

generous plaudits of my country; they are a greater reward to me,

than would have been the crown, with which Scotland sought to endow me;

for, do they not give me, what all the world cannot,—the protection of

Heaven."

"I would pray for

it!" softly answered Helen, but not venturing to look up.

"The prayer of meek

goodness, we know, ‘availeth much.’ Continue, then, to offer up that

incense for me," added he, "and I shall march forth tomorrow,

with redoubled strength; for I shall think, holy maid, that I have yet a

Marion to pray for me on earth, as well as one in heaven!"

Lady Helen’s heart beat,

at these Words; but it was with no unhallowed emotion. She withdrew

her hands from her face, and clasping them, looked up :- "Marion will

indeed echo all my prayers; end he who reads my heart, will, I trust,

grant them! They are for your life, Sir William Wallace," added she,

turning to him with agitation, "for it is menaced."

"I will inquire by

whom," answered he, "when I have first paid my duty at this

altar, for guarding it so long. And dare I, daughter of goodness, to ask

you, to unite the voice of your gentle spirit, with the secret one of

mine? I would beseech Heaven, for pardon on my own transgressions; I would

ask of its mercy, to establish the liberty of Scotland. Pray with me, Lady

Helen; and the invocations our souls utter, will meet the promise of him,

who said, ‘Where two or three are joined together in prayer, there am I

in the midst of them."

Helen looked on him with a

holy smile; and pressing the crucifix, which she held, to her lips, bowed

her head on it in mute assent. Wallace threw himself prostrate on the

steps of the altar; and the fervour of his sighs alone, breathed to his

companion, the deep devotion of his soul. How the time past, he knew not;

so was he absorbed in the communion which his spirit held in heaven, with

the most gracious of beings. But the bell of the palace striking the matin

hour, reminded him, he was yet on earth; and looking up, his eyes met

those of Helen. His devotional rosary hung on his arm: he kissed

it:—"Wear this, holy maid:" said he, "in remembrance of

this hour!" She bowed her fair neck, and he put the consecrated chain

over it: "Let it bear witness to a friendship," added he,

clasping her hands in his, "which will be cemented by eternal ties in

heaven."

Helen bent her face upon

his bands: he felt the sacred tears of so pure a compact, upon them; and

while he looked up, as if he thought the spirit of his Marion hovered

near, to bless a communion, so remote from all infringement of the

sentiment he had dedicated for ever to her, Helen raised her head—and,

with a terrible shriek, throwing her arms around the body of Wallace, he,

that moment, felt an assassin’s steel in his back, and she fell

senseless on his breast. He started on his feet; a dagger fell from his

wound to the ground, but the hand which had struck the blow, he could

nowhere see. To search further, was then impossible, for Helen lay on his

bosom like one dead. Not doubting that she had seen his assailant, and

fainted from alarm, he was laying her on the steps of the altar, that he

might bring some water from the basin of the chapel to recover her, he saw

that her arm was not only stained with his blood, but streaming with her

own. The dagger had gashed it in reaching him.

"Execrable

villain! "cried he, turning cold at the sight; and instantly

comprehending, that it was to defend him she had thrown her arms around

him, he exclaimed in a voice of agony, "Are two of the most matchless

women, the earth ever saw, to die for me !" Trembling with alarm, and

with renewed grief; for the terrible scene of Ellerslie, was now brought

in all its horrors before him; he tore off her veil, to stanch the blood;

but the cut was too wide for his surgery: and losing every other

consideration, in fears for her life, he again took her in his arms, and

bore her out of the chapel. He hastened through the dark passage, and

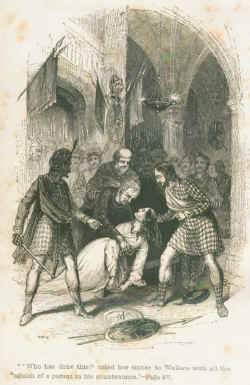

almost flying along the lighted galleries, entered the hail. The noisy

fright of the servants, as he broke through their ranks at the door,

alarmed the revellers; and turning round, what was their astonishment to

behold the Regent, pale and streaming with blood, bearing in his arms a

lady apparently lifeless, and covered with the same dreadful hue! "Execrable

villain! "cried he, turning cold at the sight; and instantly

comprehending, that it was to defend him she had thrown her arms around

him, he exclaimed in a voice of agony, "Are two of the most matchless

women, the earth ever saw, to die for me !" Trembling with alarm, and

with renewed grief; for the terrible scene of Ellerslie, was now brought

in all its horrors before him; he tore off her veil, to stanch the blood;

but the cut was too wide for his surgery: and losing every other

consideration, in fears for her life, he again took her in his arms, and

bore her out of the chapel. He hastened through the dark passage, and

almost flying along the lighted galleries, entered the hail. The noisy

fright of the servants, as he broke through their ranks at the door,

alarmed the revellers; and turning round, what was their astonishment to

behold the Regent, pale and streaming with blood, bearing in his arms a

lady apparently lifeless, and covered with the same dreadful hue!

Mar instantly recognised

his daughter; and rushed towards her, with a cry of horror. Wallace sunk,

with his breathless load, upon the nearest bench; and, while her head

rested on his bosom, ordered surgery to be brought. Lady Mar gazed on the

spectacle, with a benumbed dismay.

None present durst ask a

question, till a priest drawing near, unwrapped the arm of Helen, and

discovered its deep wound.

"Who has done

this?" cried her father, to Wallace, with all the anguish of a parent

in his countenance.

"I know not:" replied he;

"but, I believe, some villain who aimed at my life."

"Where is Lord de

Valence?’? exclaimed Mar, suddenly recollecting his menaces against

Wallace.

"I am here,"

replied he in a composed voice: " would you have me seek the

assassin?"

"No, no," cried

the Earl, ashamed of his suspicion; "but here has been some foul

work,—and my daughter is slain."

"Oh, not so!"

cried Murray, who had hurried towards the dreadful group, and knelt at her

side: "she will not die—so much excellence cannot die." A

stifled groan from Wallace, accompanied by a look, told Murray, that he

had known the death of similar excellence. With this unanswerable appeal,

the young chieftain dropped his head on the other hand of Helen; and,

could any one have seen his face, buried as it was in her robes, they

would have beheld tears of agony drawn from that ever-gay heart.

The wound was closed by the

aid of another surgical priest, who had followed the former into the hall;

and Helen sighed convulsively. At this intimation of recovery, the priest

made all excepting those who supported her, stand back. But, as Lady Mar

lingered near Wallace, she saw the paleness of his countenance turn to a

deadly hue, and his eyes closing, he sunk back on the bench. Her shrieks

now resounded through the ball; and falling into hysterics, she was taken

into the gallery, while the more collected Lady Ruthven remained, to

attend the victims before her.

At the instant Wallace

fell, De Valence, losing all self command, caught hold of De Warenne’s

arm, and whispering, "I thought it was sure ;—Long live King

Edward!" rushed out of the hail. These words revealed to De Warenne,

who was the assassin; and though struck to the soul, with the turpitude of

the deed, he thought the honour of England would not allow him to accuse

the perpetrator; and he remained silent.

The inanimate body of Wallace was

now drawn from under that of Helen: and, in the act, discovered the

tapestry-seat clotted with blood, and the Regent’s back, bathed in the

same vital stream. Having found his wound, the priests laid him on the

ground; and were administering their balsams, when Helen opened her eyes.

Her mind was too strongly possessed with the horror which had entered it

before she became insensible, to lose the consciousness of her fears; and

immediately looking around her with an aghast countenance, her sight met

the outstretched body of Wallace.—"Oh! is it so?" cried she,

throwing herself into the bosom of her father. He understood what she

meant:—"he lives, my child! but he is wounded like yourself. Have

courage; revive for his sake and for mine!"

"Helen! Helen! dear Helen

!" cried Murray, clinging to her hand, "while you live, what

that loves you can die!"

While these acclamations surrounded

her couch, Edwin, in speechless apprehension, supported the insensible

head of Wallace; and De Warenne, inwardly execrating the perfidy of De

Valence, knelt down to assist the good friars in their office.

A few minutes longer, and the

stanched blood refluxing to the chieftain’s heart, he too opened his

eyes; and instantly turning on his arm—"What has happened to me?

Where is Lady Helen ?" demanded he.

At his voice, which aroused

Helen; who, believing that he was indeed dead, was relapsing into her

former state, she could only press her father’s hand to her lips; as if

he had given the life she so valued, and bursting into a shower of

relieving tears, breathed out her rapturous thanks to God. Her low murmurs

reached the ears of Wallace.

The dimness having left his

eyes; and the blood, (the extreme loss of which, from his great

agitations, had alone caused him to swoon,) being stopped by an embalmed

bandage, he seemed to feel no impediment from his wound; and rising,

hastened to the side of Helen. Lord Mar softly whispered his

daughter,—"Sir William Wallace is at your feet, my dearest child;

look on him, and tell him that you live."

"I am well, my

father:" returned she, in a faltering voice; "and, may it indeed

please the Almighty, to preserve him!"

"I too, am alive, and

well:" answered Wallace: "but thanks to God, and to you, blessed

lady, that I am so! Had not that lovely arm, received the greater part of

the dagger, it must have reached my heart."

An exclamation of horror,

at what might have been, burst from the lips of Edwin. Helen could have

re-echoed it; but she now held her feelings under too severe a rein, to

allow them so to speak."

"Thanks to the

Protector of the just," cried she, "for your preservation! Who

raised my eyes, to see the assassin! his cloak was held before his face,

and I could not discern it; but I saw a dagger aimed at the back of Sir

William Wallace! How I caught it, I cannot tell, for I seemed to die on

the instant."

Lady Mar, having recovered,

re-entered the hall, just as Wallace had knelt down beside Helen. Maddened

with the sight of the man on whom her soul doted in such a position before

her rival, she advanced hastily; and in a voice, which she vainly

attempted to render composed and gentle, sternly addressed her

daughter-in-law; "Alarmed as I have been by your apparent danger, I

cannot but be uneasy at the attendant circumstances: tell me, therefore,

and satisfy this anxious company, how it happened that you should be with

the Regent, when we supposed you an invalid in your room; and were told,

he was gone to the citadel ?"

A crimson blush overspread

the cheeks of Helen, at this question; for it was delivered in a tone,

which insinuated that something more than accident had occasioned their

meeting: but, as innocence dictated, she answered, "I was in the

chapel at prayers; Sir William Wallace entered with the same design; and

at the moment he desired me to mingle mine with his, this assassin

appeared; and (she repeated,) I saw his dagger raised against our

protector, and I saw no more."

There was not a heart

present, that did not give credence to this account, but the polluted one

of Lady Mar. Jealousy almost laid it bare. She smiled incredulously, and

turning to the company, "Our noble friends will accept my apology, if

in so delicate an investigation, I should beg that my family alone may be

present."

Wallace perceived the

tendency of her words; and not doubting the impression they might make on

the minds of men, ignorant of the virtues of Lady Helen, he instantly

rose. "For once;" cried he, "I must counteract a lady’s

orders. It is my wish, lords, that you will not leave this place, till I

explain how I came to disturb the devotions of Lady Helen: Wearied with

festivities, in which my alienated heart can so little share, I thought to

pass an hour with Lord Montgomery in the citadel; and in seeking to avoid

the crowded avenues of the palace, I entered the chapel. To my surprise, I

found Lady Helen there. I heard her pray for the happiness of Scotland,

for the safety of her defenders; and my mind being in a frame to join in

such petitions, I apologised for my unintentional intrusion, and begged

permission to mingle my devotions with hers. Nay, impressed, and

privileged, by the sacredness of the place, I presumed still further; and

before the altar of purity, poured forth my gratitude for the duties she

had paid to the remains of my murdered wife. It was at this moment, that

the assassin appeared. I heard Lady Helen scream, I felt her fall on my

breast, and at that instant the dagger entered my back.

"This is the history

of our meeting; and the assassin, whomsoever he may be, and how long

soever he was in the church before he sought to perpetrate the

deed,—were he to speak, and capable of uttering truth, could declare no

other."

"But where is he to be

found?" intemperately, and suspiciously, demanded Lady Mar.

"If his testimony, be

necessary to validate mine;" returned Wallace, with dignity, "I

believe Lady Helen can point to his name."

"Name him, Helen; name

him, my dear cousin !" cried Murray; "that I may have some link

with thee, Oh let me avenge this deed! Tell me his name! and so yield me

all that thou canst now bestow on Andrew Murray !"

There was something in the

tone of Murray’s voice, that penetrated to the heart of Helen. "I

cannot name him whom I suspect, to any but Sir William Wallace: and I

would not do it to him," replied she, "were it not to warn him

against future danger. I did not see the assassin’s face; therefore, how

dare I set you to take vengeance on one who perchance may be innocent? I

forgive him my blood, since Heaven has spared to Scotland its

protector’s."

"If he be a Southron,"

cried Baron Hilton, coming forward,

"name him, gracious lady; and I will answer for it, that were he the

son of a king, he would meet death from our monarch, for this unknightly

outrage."

"I thank your zeal,

brave chief," replied she; "but! would not abandon to certain

death, even a wicked man. May he repent! I will name him to Sir William

Wallace alone; and when he knows his secret enemy, the vigilance of his

own honour, I trust, will be his guard.— Meanwhile, my father, I would

withdraw." Then whispering him, she was lifted in his arms, and

Murray’s, and carried from the hall.

As she moved away, her eyes

met those of Wallace. He rose; but she waved her hand to him, with an

expression in her countenance, of an adieu so firm, yet so tender, that

feeling as if he were parting with a beloved sister, who had just risked

her life for him, and whom he might never see again, he uttered not a word

to any that were present, but leaning on Edwin, left the hall by an

opposite door.

|