So large a reinforcement,

was gratefully received by Wallace; and he welcomed Maxwell with a

cordiality, which inspired that young knight with an affection equal to

his zeal.

A council being held

respecting the disposal of the new troops, it was decided that the Lennox

men must remain with their earl in garrison; while those brought by

Maxwell, and under his command, should follow Wallace in the prosecution

of his conquests, along with his own especial people.

These preliminaries being

arranged, the remainder of the day was dedicated to more mature

deliberations; to the unfolding of the plan of warfare which Wallace had

conceived. As he first sketched the general outline of his design, and

then proceeded to the particulars of each military movement, he displayed

such comprehensiveness of mind; such depth of penetration; clearness of

apprehension; facility in expedients; promptitude in perceiving, and

fixing on the most favourable points of attack; explaining their bearings

upon the power of the enemy; and where the possession of such a castle,

would compel the neighbouring ones to surrender; and where occupying the

hills, with bands of resolute Scots, would be a more efficient bulwark

than a thousand towers—that Maxwell gazed on him with admiration, and

Lennox with wonder.

Mar had seen the power of

his arms; Murray had already drunk the experience of a veteran, from his

genius; hence, they were not surprised, on hearing that which filled

strangers with amazement.

Lennox gazed on his leader’s

youthful countenance, doubting whether he really were listening to

military plans, great as general ever formed; or were visited, in vison,

by some heroic shade, who offered to his sleeping fancy, designs far

vaster than his waking faculties could have conceived. He had thought,

that the young Wallace might have won Dumbarton by a bold stroke: and

that, when his invincible courage should be steered by graver heads, every

success might be expected from his arms: but now that he heard him

informing veterans on the art of war; and saw, that when turned to any

cause of policy, "the Gordian knot of it he did unloose, familiar as

his garter" he marvelled, and said within himself, "Surely this

man is born to be a sovereign!"

Maxwell, though equally

astonished, was not so rapt. "You have made arms the study of your

life?" inquired he.

"It was the study of

my earliest days," returned Wallace. "But when Scotland lost her

freedom; as the word was not drawn in her defence, I looked not where it

lay. I then studied the arts of peace: that is over; and now the passion

of my soul revives. When the mind is bent on one object only, all becomes

clear that leads to it :- zeal, in such cases, is almost genius."

Soon after these

observations, it was admitted, that Wallace might attend Lord Mar and his

family on the morrow to the Isle of Bute.

When the dawn broke, he

arose from his heather-bed in the great tower; and having called forth

twenty of the Bothwell men to escort their lord, he told Ireland, he

should expect to have a cheering account of the wounded, on his return:

"But to assure the

poor fellows:" rejoined the honest soldier, "that something of

yourself still keeps watch over them, I pray you leave me the sturdy sword

with which you won Dumbarton. It shall be hung up in their sight ; and a

good soldier’s wounds will heal by looking on it."

[This

tower, within the fortress of Dumbarton, is still called Wallace’s

tower; and a sword is shown there, as the one that belonged to Wailace,

This sword was brought to the Tower of London, a few years ago, by the

desire of our late King, George IV., to be kept there along with other

esteemed British relics. But the Scottish nation, with a jealous pride in

their champion’s weapon of victory, worthy of them, became discontented

at its removal; the lower orders particularly, murmured at its being given

to a place, where his life had been taken from him; and our gracious

monarch commanded that it should be restored. The traveller may therefore

see it at Dumbarton still; and in the print of the old fortress which

illustrates this edition, may be traced the spot of its lasting sanctuary.—(1840.)]

Wallace smiled: "Were

it our holy King David’s we might expect such a miracle. But you are

welcome to it; and here let it remain till I take it hence. Meanwhile,

lend me yours, Stephen; for a truer never fought for Scotland."

A glow of conscious valour

flushed the cheek of the veteran. "There, my dear lord," said

he, presenting it; "it will not dishonour your hand, for it cut down

many a proud Norwegian on the field of Largs.

Wallace took the sword, and

turned to meet Murray with Edwin, in the portal. When they reached the

citadel, Lennox and all the officers in the garrison were assembled to bid

their chief a short adieu. Wallace spoke to each separately; and then

approaching the Countess, led her down the rock to the horses, which were

to convey them to the Frith of Clyde. Lord Mar, between Murray and Edwin,

followed; and the servants, and guard, completed the suite.

Being well mounted, they

pleasantly pursued their way; avoiding all inhabited places, and resting

in the deepest recesses of the hills. Lord Mar had proposed travelling all

night; but at the close of the evening, his Countess complained of

fatigue, declaring she could not advance further than the eastern bank of

the river Cart. No shelter appeared in sight, excepting a thick and

extensive wood of hazels; but the air being mild, and the lady declaring

her inability of moving on, Lord Mar at last became reconciled to his wife

and son passing the night with no other canopy than the trees. Wallace

ordered cloaks to be spread on the ground for the Countess and her women;

and seeing them laid to rest, planted his men to keep guard around the

circle.

The

moon had sunk in the west, before the whole of his little camp were

asleep. But when all seemed composed, he wandered forth by the dim light

of the stars, to view the surrounding country; a country he had so often

traversed in his boyish days. A little onwards, in green Renfrewshire, lay

the lands of his father; but that Ellerslie of his ancestors, like his own

Ellerslie of Clydesdale, his country’s enemies had levelled with the

ground! He turned in anguish of heart towards

the south, for there less racking remembrances hovered over the distant

hills.

The

moon had sunk in the west, before the whole of his little camp were

asleep. But when all seemed composed, he wandered forth by the dim light

of the stars, to view the surrounding country; a country he had so often

traversed in his boyish days. A little onwards, in green Renfrewshire, lay

the lands of his father; but that Ellerslie of his ancestors, like his own

Ellerslie of Clydesdale, his country’s enemies had levelled with the

ground! He turned in anguish of heart towards

the south, for there less racking remembrances hovered over the distant

hills.

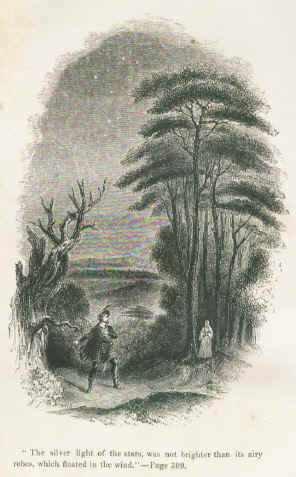

Leaning on the shattered stump of an

old tree, he fixed his eyes on the far-stretching plain, which alone

seemed to divide him from the venerable Sir Ronald Crawford, and his

youthful haunts, at Ayr. Full of thoughts of her who used to share those

happy scenes—he heard a sigh behind him. He turned round, and beheld a

female figure disappear amongst the trees. He stood motionless: again it

met his view: it seemed to approach. A strange emotion stirred within him.

When he last passed these borders, he was bringing his bride from Ayr!

What then was this ethereal visitant? The silver light of the stars, was

not brighter than its airy robes, which floated in the wind. His heart

paused—it beat violently—still the figure advanced. Lost in the

wildness of his imagination, he exclaimed, "Marion!" and darted

forwards, as if to rush into her embrace. But it fled, and again vanished.

He dropped upon the ground in speechless disappointment.

"‘Tis false !" cried he,

recovering from his first expectation; "‘tis a phantom of my own

creating. The pure spirit of Marion would never fly me: I loved her too

well. She would not thus redouble my grief. But I shall go to thee, wife

of my soul !" cried he; "and that is comfort. Balm,

indeed, is the Christian’s hope !"

Such were his words, such were his

thoughts, fill the coldness of the hour, and the exhaustion of nature,

putting a friendly seal upon his senses, he sunk upon the bank, and fell

into a profound sleep.

When he awoke, the lark was

carolling above his head; and to his surprise he found that a plaid was

laid over him. He threw it off, and beheld Edwin seated at his feet.

"This has been your doing, my kind brother," said he; "but

how came you to discover me?"

"I missed you, when

the dawn broke; and at last found you here, sleeping under the dew."

"And has none else

been astir ?" inquired Wallace, thinking of the figure he had seen.

"None that I know of.

All were fast asleep, when I left the party."

Wallace began to fancy that

he had been labouring under the impressions of some powerful dream, and

saying no more, he returned to the wood. Finding every body ready, he took

his station; and setting forth, all proceeded cheerfully, though slowly,

through the delightful valleys of Barochan. By sunset they arrived at the

point of embarkation. The journey ought to have been performed in half the

time; but the Countess petitioned for long rests: a compliance with which

the younger part of the cavalcade conceded with reluctance.