THE generality of his prisoners,

Bruce directed should be kept safe in the citadel; but to Mowbray he gave

his liberty; and ordered every means to facilitate the commodious journey

of that brave knight; whom he bad requested to convey the insane Lady

Strathearn to the protection of her husband.

Mowbray accepted his

freedom with gratitude; and gladly set forth with his unhappy charge, to

meet his sovereign. Expectation of Edward’s approach, had been the

reason of his withdrawing his herald from the camp of Bruce; and though

the King did not arrive time enough to save Stirling, Mowbray yet hoped he

might still be continuing his promised march. This anticipation, the

Southron’s loyalty would not allow him to impart to Bruce; and he bade

that generous prince adieu, with the full belief of soon returning to find

him the vanquished of Edward.

At the decline of day,

Bruce returned to his camp, to pass the night in the field with his

soldiers; intending next morning to give his last orders to the

detachments, which he meant to send out under the command of Lennox and

Douglas, to disperse themselves over the border counties; and there keep

station, till that peace should be signed by England, which he was

determined, by unabated hostilities, to compel.

Having taken these measures for the

security of his kingdom, and the establishment of his own happiness, he

had just returned to his tent on the banks of Bannockburn, when Grimsby, his

now faithful attendant, conducted an armed knight into his presence. The

light of the lamp which stood on the table, streaming full on the face of

the stranger, discovered to the King, his English friend the intrepid

Montgomery. With an exclamation of glad surprise,

Bruce would have clasped him in his arms; but Montgomery, dropping on his

knee, exclaimed, "Receive a subject, as well as a friend, victorious

and virtuous Prince!—I have forsworn

the vassalage of the Plantagenets; and thus, without title or land, with

only a faithful heart, Gilbert Hambledon comes to vow himself yours, and

Scotland’s, for ever."

Bruce raised him from the

ground; and welcoming him with the warm embrace of friendship, inquired

the cause of so extraordinary an abjuration of his legal sovereign.

"No light matter," observed the King, "could have so

wrought upon my noble Montgomery!"

"Montgomery no more!"

replied the Earl, with indignant eagerness: "when I threw the

insignia of my earldom at the feet of the unjust Edward, I told him, that

I would lay the saw to the root of the nobility I had derived from his

house, and cut it through: that I would sooner leave my posterity, without

titles, and without wealth, than deprive them of real honour. [This

event is perpetuated, in the crest of the noble family of Hamilton in

Scotland.—(1809.)] I have done as I said!—

And yet I come not without a treasure; for the sacred corse of William

Wallace is now in my barque, floating on the waves of the Forth!"

The subjugation of England, would

hardly have been so welcome to Bruce, as this intelligence. He received it

with an eloquent, though unutterable look of gratitude. Hambledon

continued: "On the tyrant summoning the peers of England to follow

him to the destruction of Scotland, Gloucester got excused under a plea of

illness: and I, could not but show a disinclination to obey. This

occasioned some remarks from Edward, respecting my known attachment to the

Scottish cause; and they were so couched, as to draw from me this honest

answer:—My heart would not, for the wealth of the world, permit me to

join in the projected invasion; since I had seen the spot in my own

country, where a most inordinate ambition had cut down the flower of all

knighthood, because he was a Scot who would not sell his birthright!—The

King left me in wrath, and threatened to make me recant my words:—I as

proudly declared, I would maintain them. Next morning, being in waiting on

the Prince, I entered his chamber, and found John le de Spencer (the

coward who so basely insulted Wallace on the day of his condemnation); he

was sitting with his highness. On my offering the services due from my

office, this worthless minion turned on me, and accused me of having

declined joining the army, for the sole purpose of executing some plot in

London, devised between me and my Scottish partisans, for the subversion

of the English monarchy. I denied the charge. He enforced it with oaths,

and I spurned his allegations. The Prince, who believed him, furiously

gave me the lie, and commanded me, as a traitor, to leave his presence. I

refused to stir an inch, till I had made the base heart of Le de Spencer

retract his falsehood. The coward took courage on his master’s support,

and, drawing his sword upon me, in language that would blister my tongue

to repeat, threatened to compel my departure. He struck me on the face

with his weapon. The arms of his Prince could not then save him; I thrust

him through the body, and he fell. Edward ran on me with his dagger, but I

wrested it from him. Then it was, that in reply to his menaces, I revoked

my fealty, to a sovereign I abhorred, a Prince I despised. Leaving his

presence, before the fluctuations of so versatile a mind could fix upon

seizing me, I hastened to Highgate, to convey away the body of our friend

from its brief sanctuary. The same night I embarked it, and myself, on

board a ship of my own; and am now at your feet, brave and just King! no

longer Montgomery, but a true Scot in heart and loyalty,"

"And, as a kinsman, generous Hambledon!"

returned Bruce, "I receive, and will portion thee. My paternal lands

of Cadzow, on the Clyde, shall be thine for ever. And may thy posterity be

as worthy of the inheritance, as their ancestor is of all my love and

confidence!" [These circumstances, relating

to the first establishment of the noble family of Hamilton (by the old

historians called Hampton, or Hameldon,) in Scotland, are particularly

recorded. The lands of Cadzow are now called Hamilton, from their owners,

earls and dukes of that name. The crest of the family arms is a tree with

a saw in it; and the motto, through.—(1809.)]

Hambledon, having received

his new sovereign’s directions concerning the disembarkation of those

sacred remains, which the young King declared he should welcome as the

pledge of Heaven to bless his victories with peace; returned to the haven,

where Wallace rested in that sleep which even the voice of friendship

could not disturb.

At the hour of the midnight

watch, the trumpets of approaching heralds resounded without the camp.

Bruce hastened to the council-tent, to receive the now anticipated

tidings. The communications of Hambledon had given him reason to expect

another struggle for his kingdom; and the message of the trumpets declared

it might be a mortal one.

At the head of a hundred

thousand men, Edward had forced a rapid passage through the lowlands; and

was now within a few hours march of Stirling; fully determined to bury

Scotland under her own slain, or, by one decisive blow, restore her to his

empire.

When this was uttered by the English

herald, Bruce turned to Ruthven with an heroic smile: "Let him come,

my brave barons! and he shall find that Bannockburn shall page with Cambus-Kenneth!"

The strength of the

Scottish army did not amount to more than thirty thousand men, against

this host of Southrons. But the relics of Wallace were there! His spirit

glowed in the heart of Bruce. The young monarch lost not the advantage of

choosing his ground first; and therefore as his power was deficient in

cavalry, he so took his field, as to compel the enemy to make it a battle

of infantry alone.

To protect his exposed

flank from the innumerable squadrons of Edward, he dug deep and wide pits

near to Bannockburn; and having overlaid their mouths with turf and

brushwood, proceeded to marshal his little phalanx on the shore of that

brook, till his front stretched to St. Ninian’s monastery.

The centre was led by Lord

Ruthven, and Walter Stewart; the right, owned the valiant leading of

Douglas and Ramsay, supported by the brave young Gordon with all his clan;

and the left was put in charge of Lennox; with Sir Thomas Randolph, a

crusade chieftain, who, like Lindsay and others, had lately returned from

distant lands, and now zealously embraced the cause of his country.

Bruce stationed himself at

the head of the reserve: with him, were the veterans Loch-awe and

Kirkpatrick; and Lord Bothwell, with the true De Longueville, and the men

of Lanark; all determined to make this division the stay of their little

army; or the last sacrifice for Scottish liberty, and its martyred

champion’s corse. There, stood the sable hearse of Wallace; and the

royal standard, struck deep into the native rock of the ground, waved its

blood-red volumes over his sacred head.

"By that Heaven-sent

palladium of our freedom;" cried Bruce, pointing to the bier,

"we must this day stand or fall. He who deserts it, murders William

Wallace anew!"

At this appeal, the chiefs

of each battalion assembled round the hallowed spot; and laying their

hands on the pall, swore to fill up one grave with their dauntless

Wallace, rather than yield the ground which he had rendered doubly

precious, by having made it the scene and the guerdon of his invincible

deeds! When Kirkpatrick approached the side of his dead chief, he burst

into tears; and his sobs alone proclaimed his participation in the

solemnity. The vow spread to the surrounding legions; and was echoed, with

mingled cries and acclamations, from the furthest ranks.

"My leader, in death as in

life!" exclaimed Bruce, clasping his friend’s sable shroud to his

heart; "thy pale corse shall again redeem the country which cast

thee, living, amongst devouring lions! Its presence shall fight and

conquer for thy friend and King!"

Before the chiefs turned to

resume their martial stations, the abbot of Inchaffray, drew near with the

mysterious iron box, which Douglas had caused to be brought from St.

Fillan’s priory. On presenting it to the young monarch, he repeated the

prohibition which had been given with it; and added, "Since, then,

these canonized relics (for none can doubt they are so,) have found

protection under the no less holy arm of St. Fillan; he now delivers them

to your youthful majesty, to penetrate their secrete, and to nerve your

mind with redoubled trust in the saintly host."

"The saints are to be

honoured, reverend father; and on that principle I shall not invade their

mysteries, till the God in whom alone I trust, marks me with more than the

name of king; till, by a decisive victory, he establishes me the approved

champion of my country; the worthy successor of him, before whose mortal

body, and immortal spirit, I now emulate his deeds, But as a memorial,

that the host of heaven do indeed lean from their bright abodes, to wish

well to this day, let these holy relics repose with those of the brave,

till the issue of the battle."

Bruce, having placed his array, disposed

the supernumeraries of his army, the families of his soldiers, and other

apparently useless followers of the camp, in the rear of an adjoining

hill.

By daybreak, the whole of the

Southron army came in view. The van, consisting of archers and men at

arms, displayed the banner of Earl de Warenne; the main body was led on by

Edward himself, supported by a train of his most redoubted generals. As

they approached, the Bishop of Dunkeld stood on the face of the opposite

hill, between the abbots of Cambus-Kenneth and Inchaffray, celebrating

mass in the sight of the opposing armies. He passed along in front of the

Scottish lines barefoot, with the crucifix in his hand; and in few but

forceful words, exhorted them by every sacred hope, to fight with an

unreceding step for their rights, their King, and the corse of William

Wallace! At this adjuration, which seemed the call of Heaven itself, the

Scots fell on their knees, to confirm their resolution with a vow. The

sudden humiliation of their posture, excited an instant triumph in the

haughty mind of Edward, and spurring forward, he shouted aloud, "They

yield! They cry for mercy!"—"They cry for mercy!"

returned Percy, trying to withhold his Majesty, "but not from us. On

that ground, on which they kneel, they will be victorious, or find their

graves!"

[This true description of the

leading facts of that great Scottish battle has often sounded its chord in

many a Scottish heart: said, in honour of the accuracy of her painting,

the author has received many warmhearted testimonies; even so far, as in

provincial theatres, concert rooms, and on military parades, being saluted

by the Scottish bands, with the aid patriotic air of—.

"Seots, wha hae wi’ Wallace

bled!

Scots, wha Bruce hath often led! "—

the true pibroch of Scotland! Indeed

the stone in which the standard of Bruce, in the battle of Bannockburn,

was fixed, is still visible; and every narrator of the legends connected

with that memorable field, tells of the superstitious sanctity attributed

to the iron box brought from St. Filan’s.—-(1820.)]

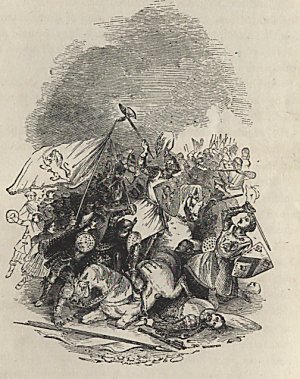

The King contemned this

opinion of the Earl; and inwardly believing that, now Wallace was dead, he

need fear no other opponent, (for he knew not that even his cold remains

were risen in array against him,) he ordered his men to charge. The

horsemen, to the number of thirty thousand, obeyed; and rushing forward,

with the hope of overwhelming the Scots ere they could rise from their

knees, met a different destiny. They found destruction, amid the trenches,

and on the spikes in the way; and with broken ranks, and fearful

confusion, fell, or fled under the missive weapons, which poured on them

from a neighbouring hill. De Valence was overthrown, and severely wounded;

and being carried off the field, filled the rear ranks with dismay; while

the King’s division was struck with consternation at so disastrous a

commencement of an action, in which they had promised themselves an easy

victory. Bruce seized the moment of confusion; and seeing his little army

distressed by the arrows of the English, he sent Bothwell round with a

resolute body of men, to drive those destroying archers, from the height

which they occupied. This was effected; and Bruce coming up with his

reserve, the battle in the centre, became close, obstinate, and decisive.

Many fell before the determined arm of the youthful King; but it was the

fortune of Bothwell to encounter the false Monteith, in the train of

Edward. The Scottish Earl was then at the head of his intrepid Lanark men:

"Fiend of the most damned treason:" cried he, "vengeance is

come!" and with an iron grasp, throwing the traitor into the midst of

the faithful clan; they dragged him to the hearse of their chief; and

there, on the skirts of its pall, the wretched villain breathed out his

treacherous breath, under the strokes of a hundred swords.

"So," cried the veteran Ireland, "perish the murderers of

William Wallace!"—"So," shouted the rest, "perish

the enemies of the bravest, the most loyal of Scots! .the benefactor of

his country!"

At this crisis, the women

and followers of the Scottish camp, hearing such triumphant exclamations

from their friends, impatiently quitted their station behind the bill, and

ran to the summit, waving their scarfs and plaids in exultation of the

supposed victory. The English, mistaking these people for a new army, had

not power to recover from the increasing confusion which had seized them

on King Edward himself receiving a wound; and, panic-struck with the sight

of their generals falling around them, they flung down their arms and

fled. The King narrowly escaped; but being mounted on a stout and fleet

horse, he put him to the speed, and reached Dunbar: whence the young Earl

of March, being as much attached to the cause of England, as his father

had been, instantly gave him a passage to England.

The Southron camp, with all

its riches, fell into the hands of Bruce. But while his chieftains pursued

their gallant chase, he turned his steps from warlike triumph, to pay his

heart’s honours to the remains of the hero whose blood had so often

bathed Scotland’s fields of victory. His vigils were again beneath that

sacred pall:—for so long had been the conflict, that night closed in,

before the last squadrons left the banks of Bannockburn.

At the dewy hour of morn,

Bruce reappeared on the field. His helmet was royally plumed; and the

golden lion of Scotland gleamed from under his sable surcoat. Bothwell

rode at his side. The troops he had retained from the pursuit, were drawn

out in array. In a brief address, he unfolded to them the solemn duty to

which he had called them; to see the bosom of their native land receive

the remains of Sir William Wallace. "He gave to you your homes, and

your liberty! grant, then, a grave, the peace of the tomb, to him, whom

some amongst you repaid with treachery and death !"

At these words a cry, as if

they beheld their betrayed chief slain before them, issued from every

heart.

The news had spread to the

town; and, with tears and lamentations, a vast crowd collected round the

royal troop. Bruce ordered his bards to raise the sad coronach; and the

march commenced towards the open tent that canopied the sacred remains.

The whole train followed in speechless woe, as if each individual had lost

his dearest relative. Having passed the wood, they came in view of the

black hearse, which contained all that now remained of him who had so

lately crossed these precincts in all the panoply of triumphant war: in

all the graciousness of peace, and love to man! The soldiers, the people,

rushed forward; and precipitating themselves before the bier, implored a

pardon for their ungrateful country. They adjured him, by every tender

name of father, benefactor, and friend! and in such a sacred presence,

forgetting that their King was by, gave way to a grief, which most

eloquently told the young monarch, that he who would be respected after

William Wallace, must not only possess his power and valour, but imitate

his virtues.

Scrymgeour, who had well

remembered his promise to Wallace on the battlements of Dumbarton, with a

holy reference to that vow, now laid the standard of Scotland upon the

pall. Hambledon placed on it, the sword and helmet of the sacrificed hero.

Bruce observed all in silence. The sacred burden was raised. Uncovering

his royal head, with his kingly purple sweeping in the dust he walked

before the bier; shedding tears, more precious in the eyes of his

subjects, than the oil which was soon to pour upon his brow. As he thus

moved on, he heard acclamations, mingle with the voice of sorrow.

"This is our King, worthy to have been the friend of Wallace! worthy

to succeed him in the kingdom of our hearts!"

At the gates of Cambus-Kenneth,

the venerable abbot appeared at the head of his religious brethren; but,

without uttering the grief that shook his aged frame, he raised the golden

crucifix over the head of the bier; and after leaning his face for a few

minutes on it, preceded the procession into the church. None but the

soldiers entered. The people remained without; and as the doors closed,

they fell on the pavement, weeping as if the living Wallace had again been

torn from them.

On the steps of the altar,

the bier rested. The Bishop of Dunkeld, in his pontifical robes, received

the sacred deposit, with a cloud of incense; and the pealing organ,

answered by the voices of the choristers, breathed the solemn requiem of

the dead. The wreathing frankincense parted its vapour, and a win but

beautiful form, clasping an urn to her breast, appeared, stretched on a

litter, and was borne towards the spot. It was Helen, brought from the

adjoining nunnery; where, since her return to these once dear shores, now

made a desert to her, she had languished in the gradual decay of the

fragile bonds which alone fettered her mourning spirit, eager for release.

All night had Isabella

watched by her couch, expecting that each succeeding breath would be the

last her beloved sister would draw in this calamitous world; but, its her

tears fell in silence from her cheek, upon the cold forehead of Helen, the

gentle saint understood their expression, and looking up; "My

Isabella," said she, "fear not.—My Wallace is returned. God

will grant me life to clasp his blessed remains!"

Full of this hope, she was

borne, almost a passing spirit, into the chancel of Cambus-Kenneth.—Her

veil was open, and discovered her face, like tone just awakened from the

dead: it was ashy pale; but it bore a celestial brightness; which, like

the silver lustre of the moon, declared its approach to the fountain of

its glory. Her eye fell on the bier: and, with a momentary strength she

sprang from the couch, on which she had leaned in dying feebleness, and

threw herself upon the coffin.

There was an awful pause,

while Helen seemed to weep. But so, was not her sorrow to be shed. It was

locked within the flood-gates of her heart.

In that suspension of the

soul, when Bothwell knelt on one side, of the bier, and Ruthven bent his

knee on the other, Bruce stretched out his hand to the weeping Isabella: "Come

hither; my youthful bride, and let thy first duty be paid to the shrine of

thy benefactor, and mine!—So may we live, sweet excellence; and so may

we die, if the like may be our meed of heavenly glory!" Isabella

threw herself into his arms, and wept aloud. Helen, slowly raising her

head at these words, regarded her sister with a look of awful tenderness;

then turning her eyes back upon the coffin, gazed on it as if they would

have pierced its confines; and clasping the urn earnestly to her heart,

she exclaimed, "‘Tis come! the promise—Thy bridal bed shall be

William Wallace’s grave."

Bruce and Isabella, not

aware that she repeated words which Wallace had said to her, turned to her

with portentous emotion. She understood the terrified glance of her

sister, and with a smile, which spoke her kindred to the soul she was

panting to rejoin, she, answered, "I speak of my own espousals. But

ere that moment is, and I feel it near— let my Wallace’s hallowed

presence, bless your nuptials!—-Thou wilt breathe thy benediction

through my lips!" added she, laying her hand on the coffin, and

looking down on it, as if she were conversing with its inhabitant.

"O! no, no!"

returned Isabella, throwing herself on her knees before the almost

unembodied aspect of her sister: "Let me ever be the sharer of your

cell, or take me with you to the kingdom of heaven!" "it is thy

sister’s spirit that speaks:" cried Dunkeld, observing the awe,

which not only shook the tender frame of Isabella, but had communicated

itself to Bruce; who stood in heart-struck veneration before the yet

unascended angel; "holy inspiration," continued the bishop;

"beams from her eyes; and as ye hope for further blessings, obey its

dictates!"

Isabella bowed her head in

acquiescence. As Bruce approached to take his part in the sacred rite, he

raised the hand, which lay on the pall to his lips. The ceremony began;

was finished!—As the bridal notes resounded from the organ, and the

royal pair rose from their knees, Helen held her trembling hands over

them.—She gasped for breath; and would have sunk without a word, had not

Bothwell supported her shadowy form upon his breast she looked round on

him, with a grateful though languid smile, and with a strong effort

spoke:—"Be you blest in all things, as Wallace would have blessed

you!—From his side, I pour out my soul upon you, my sister—my

being!—and, with its inward-breathed prayers, to the Giver of all Good,

for your eternal happiness, I turn, in holy faith—to my long-looked-for

rest!"

Bruce and Isabella wept in

each other’s arm. Helen slid gently from the bosom of Bothwell,

prostrate on the coffin; and uttering, in a low tone, "I waited only

for this!—We have met—I unite thy noble heart to thee again—I claim

my brother—at our Father’s hands—in mercy!—in love—by his

all-blessed Son!"—Her voice gradually faded away, as she murmured

these broken sentences, which none but the close and attentive ear of

Bothwell heard. But he caught not the triumphant exclamation of her soul;

which spoke, though her lips ceased to move, and cried to the attending

angels—"Death, where is thy sting? Grave, where is thy

victory?"

In this awful moment, the

abbot of lnchaffray, believing the dying saint was prostrate in prayer,

laid his hand on the iron box, which stood at the foot of Wallace’s

bier—"Before the sacred remains, of the once champion of Scotland,

and in the presence of his royal successor" exclaimed the abbot,

"let this mysterious coffer of St. Fillan’s, be opened; to reward

the deliverer of Scotland, according to its intent!" "If it were

to contain the relics of St. Fillan himself:" returned the King,

"they could not meet a holier bosom than this!" and resting the

box on the coffin, he unclasped the lock; and the Regalia of Scotland was

discovered! At this sight, Bruce exclaimed, in an agony of grateful

emotion, "Thus did this truest of human beings, protect my rights,

even while the people I had deserted, and whom he had saved, knelt to him

to wear them all!"

"And thus Wallace

crowns thee!" said Dunkeld, taking the diadem from its coffer, and

setting it on Bruce’s head.

"My husband, and my

king!" gently exclaimed Isabella, sinking on her knee before him, and

clasping his hand to her lips.

"Hearest thou that? my

beloved Helen!" cried Bothwell, touching the clasped hands, which

rested on the coffin. He turned pale, and looked on Bruce. Bruce, in the

glad moment of his joy at this happy consummation of so many years of

blood, observed not his glance; but, in exulting accents, exclaimed,

"Look up," my sister; and let thy soul, discoursing with our

Wallace, tell him that Scotland is free, and Bruce a king indeed!"

She spoke not, she moved

not. Bothwell raised her clay-cold face. "That soul has fled, my

Lord!" said he; "but from yon eternal sphere, they, now,

together, look upon your joys. Here let their bodies rest; for they loved

in their lives, and in their deaths they shall not be divided"‘

Before the renewing of the

moon, whose waning light witnessed their solemn obsequies,—the aim of

Wallace’s life, the object of Helen’s prayers, was accomplished.—

Peace reigned in Scotland.— The discomfited King Edward, died of chagrin

at Carlisle; and his humbled son and successor, sent to offer such

honourable terms of pacification, that Bruce gave them acceptance; and a

lasting tranquillity spread prosperity and happiness throughout the land.