|

There

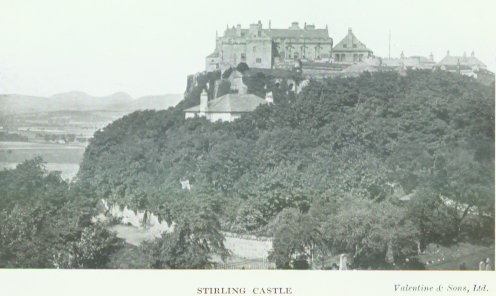

are some Castles in Scotland which have become

famous rather in consequence of their beauty than their strength; but it

will be found that those of them which are most memorable in history are

noteworthy for both these elements. Edinburgh Castle, for instance, whilst

long celebrated as the Maiden Fort which defied the invader, commands a

prospect that alone would have made it worthy of remembrance In like

manner the Castle of Stirling would have been noticeable for its

picturesque situation, even had there been no important events connected

with it. The beauty of its site attracted the notice of the Kings and

Princes of early times as forming the position for a Royal residence,

while its strength formed no mean recommendation as a protection for the

Court in a lawless age. Hence Dumbarton Castle, Stirling Castle and

Edinburgh Castle have at different times been the seats of Kingly power.

Dumbarton was replaced by Stirling, then Perth, before the centre of

government was settled at Edinburgh.

There are many derivations

of the name of Stirling given by students of Place-names, though these are

mostly variations of one idea. Its old name of "Strila" is evidently

compounded of the Celtic words strigh (strife) and laigh

(the bending of the bow), and it has been alleged that the name arose from

the fact that the archery butts were set up here at an early date. Its

second name was "Stryvelin," usually interpreted as "strife," and is

poetically applied to the meeting of the three waters—Forth, Allan and

Teith—near the town. The most reasonable notion seems to be that which

derives its origin from Ster (a mountain) and lin (a river),

since this exactly describes the position of the town and the Castle. And

the fact that its alternative title of "Snawdun," signifying "the

fortified hill on the river" gives additional weight to this conjecture,

and finds corroboration in the couplet by old Sir David Lyndsay :—

"Adew! fair Snawdun, with

thy towris hie,

Thy Chapell Royal, Park, and

Tabyll Round."

No one can wonder that a

Castle so beautifully situated became a favourite residence with the

monarchs of Scotland.

The hill upon which the

Castle is built, though not in itself of any great height, towers so

precipitously over the Carse of Stirling that it gains an advantage, so

far as stretch of vision is concerned over more lofty mountains. The

stream of the Forth, which is here a goodly river, flows around the base

of the eminence, and meanders through the level country betwixt Stirling

and the sea, with many a graceful curve and winding sweep. As seen from

the Castle the view is exquisite. To the north-eastward stands the

solitary peak of Abbey Craig, now crowned by the Wallace Monument, and

overlooking the ever-memorable field of Bannockburn. Here, too, may be

seen the ruins of Cambuskenneth Abbey, once a royal sepulchre; while the

dark purple of the Ochil Hills forms a dim receding background. Westward

the wide carse of Stirling stretches far as the eye can reach, presenting

an unbroken surface of fertile and variegated country, dotted with towns

and villages in rich profusion. The majestic river winds with serpent-like

and sinuous writhings through the green plain, casting abroad its gigantic

folds, like some stupendous chain, whose argent gleaming reflects the rays

of the sun with greater intensity because mellowed by the tint of the

verdant and fruitful banks through which it pursues its course.

There are few prospects in

"braid Scotland" more charming than this, and whilst the Castle was deemed

important enough to be set aside as the dowry of the Scottish Queens, the

lovely scene which lies before it did not escape the notice of the ancient

ballad-singers. The river Forth here takes so many tortuous windings that

in the space of six miles the stream measures twenty-four miles; and these

wimpling links are often celebrated in early Scottish song:-

"Are these the Links o’ Forth, she

said,

Or are they Crooks o’ Dee,

Or the bonnie wood o’ Warroch-head

That I sae fain wad see?"

In very distant times Stirling

formed the boundary of the great Nemus Caledonia, or Caledonian Forest,

which was an insuperable barrier against Roman invasion. And at this day

the ancient Seal of the Burgh of Stirling shows a Forest, supposed to be

this Scottish Wood, together with a Cross, explained as signifying the

great Cross set up at the Castle, and a Bridge emblematical of the Bridge

of Forth, both of which erections were due to the Northumbian invasion in

855, at which time the Castle changed hands. Tradition asserts that from

the Castle the intelligent observer may descry thirteen battle-fields,

among which may be mentioned Bannockburn, Sauchie Burn, Falkirk (twice),

Sherifimuir, and Stirling Bridge. It is evident that a locality such as

this must be rich in historic lore; and the Castle of Stirling has been

the scene of many deeds of crime, of many revelries and pageants, only

equalled by Edinburgh, the Capital of Scotland. Some of these incidents

may be related, even though they are not placed in chronological order.

The Castle of Stirling had been

conferred by James I. upon his English bride, Lady Joanna de Beaufort—the

heroine of "The King’s Quhair "—as her dowry, and it was here that her

son, afterwards James II., was born in 1430, being the younger twin-son of

the King, the elder of whom, Alexander, died in infancy. Some of the

chroniclers state that the birth of the twins took place at Holyrood; but

possibly this may be an error caused by the anointing and crowning there

of James II. in 1437, a year after his father’s assassination at Perth.

This may be doubtful; but it is certain that the King (James II.), in

Febnary 1451-52, perpetrated at Stirling one of the blackest deeds of

treachery which is recorded against the whole Stewart race to which he

belonged.

From the time of King Robert the

Bruce the family of Douglas, whose founder was the fellow-warrior of that

King, had been rising into increased power. Honours were showered upon

them by successive Monarchs—at first in gratitude but latterly in fear.

For the dominion of the Douglases spread so widely, and drew within its

scope so many warlike nobles that the Lanarkshire Earl might soon

out-number the Crown in wealth, as in forces. As it was impossible,

therefore, for the King to quarrel with so powerful a subject, he

endeavoured to win the Earl over by making him Lieutenant-General of the

Kingdom. But the possession of so important a post seems rather to have

inflamed the ambition of the Earl than bound him to the King. So

overbearing, indeed, had he become that the Monarch, whose favourite

Douglas had been, was compelled to withdraw the Royal patronage, and to

deprive the Earl of his post. The disappointed nobleman retired in chagrin

to his Castle of Douglas and meditated schemes of revenge against the King

and the Court party.

Nor was he long without opportunity

of gratifying his vindictive spirit. One after another of the King’s

followers were attacked upon some pretext, sufficient in those times to

justify sudden reprisal; and the Monarch soon found that he had made a

dangerous enemy in the Earl of Douglas. But it was not until he had openly

disregarded the King’s mandate that he was finally abandoned. The Earl had

summoned his vassals to meet him upon a special occasion. Amongst those

whom he had thus summoned was M’Lellan, known as the Tutor of Bomby, in

Kirkcudbrightshire. This unfortunate man had provoked the Earl by refusing

to join with him against the King; and Douglas had kidnapped this daring

vassal, and carried him off to the Castle of Thrieve. The uncle of

M’Lellan, Sir Patrick Gray, Captain of the King’s Guard—then a favourite

with the King—obtained a Royal mandate ordering Douglas to release

M’Lellan.

Sir Patrick set forth with this

missive, but was met by the Earl with every demonstration of amity,

inviting him to dinner, and protracting the meal till his own evil purpose

had been accomplished. Then he led Gray into the courtyard; he pointed to

a dead body lying there, and said:

"Sir Patrick, the letter which you

bear comes too late. There lies your sister’s son, without his head. To

his body thou art welcome, an’ it please thee to mell with it." -

"Nay," said Sir Patrick, "sen thou

hast ta’en the head, make what thou wilt of the body; for thou shalt

answer shortly to the King for both." And mounting in hot haste, Gray sped

to Edinburgh to report this outrage, pursued by the myrmidons of Douglas.

The recital of this new attack upon

his kingly prerogative decided the King to adopt severe measures against

the Earl of Douglas; but he took a crafty method of doing so.

Having discovered that Douglas, who

ruled in the south, had agreed with the Earl of Ross, who was all-powerful

in the north, and the Earl of Crawford, whose influence spread throughout

the east coast, to maintain each others quarrels, even against the King

himself, his Majesty, fearful of the conspiracy, summoned his Parliament

to Stirling to advise upon it. After deliberation, it was decided to bring

Douglas to this conference, and to endeavour by argument to break this

alliance. A safe conduct, under the hand and Seal of the King, was sent to

him requesting his attendance. Trusting to the honour of his liege-lord,

Douglas approached with but a few adherents, and even those were excluded

from the precincts of the royal palace.

Alone, therefore, the Black Earl

entered that portal through which he never more should pass. The King met

him with accustomed cordiality, and, after supper, retired with him and a

few of his counsellors to an inner apartment to discuss the affairs of

State. Here James thought to persuade Douglas to abandon his league with

the Earls Ross and Crawford; but threat and persuasion were alike

powerless upon him. Irritated beyond measure by this continued obstinacy,

and well aware of the result of too great leniency towards him, the King

at last drew his dagger, and exclaiming "By Heaven, if you will not break

this league, I will," he stabbed the unfortunate Earl to the heart. The

old enemy of Douglas, Sir Patrick Gray, with all the bitterness of his

last grudge against him, was not slow to aid the King in his felon intent,

and the body of the murdered nobleman was thrown from the window of that

apartment in the Castle which is still called "the Douglas Room."

However disreputable the means

employed, it is certain that the step which the King had taken ultimately

compelled him to adopt repressive measures against the Scottish nobility,

and finally to overcome and destroy the long-established feudal system.

And, as a curious instance of historical retribution, it may be mentioned

that the murder of James III. (son of James II.) at Sauchie Burn, was

popularly attributed to the son of this same Sir Patrick Gray, the King’s

accomplice in his attack upon the Earl of Douglas.

Many additions were made to the

Castle during the turbulent reign of James III., who made it his favourite

residence. He built the large hall, now called the Parliament House, and

erected the Chapel Royal, celebrated in song by the poets of the period;

which was afterwards demolished by James VI. to make way for a more

pretentious structure. There is little doubt that the violent death of

James III. was immediately caused by the treachery of the Castellane whom

he had put in charge of Stirling, and who refused to open the gate to the

King while in retreat.

During the reign of James V.,

Stirling was the scene of a very ludicrous scientific fiasco. The

reputation which the King had gained on the Continent as a lover of

literature and art had attracted many foreign adventurers to the Scottish

shore. Poets, musicians, and alchemists flocked to the Court whose Monarch

laid claim to a wide sympathy with the art of each professor; and as the

craze of the search after the "philosopher’s stone" was not yet exploded,

King James fell an easy prey to charlatanry and imposture. Chief among the

alchemists that had gained an ascendancy over the King was an Italian

monk, who so dazzled his dupe by unlimited promises that nothing was

withheld from him. He was made Abbot of Tungland, and assigned apartments

in the Castle that he might pursue his Rosicrucian studies unmolested.

That this monk was neither a

Dowsterswivel nor a Subtle, may be surmised from the fact that he so far

believed in his power as to experiment on himself. Having made aerial

flight his study for a considerable time, he at last announced that he had

solved the problem which had perplexed mankind till his day. He invited a

large company to witness his triumph over gravitation; and having mounted

the battlements of the Castle he boldly flung himself from the parapet.

But he had miscalculated the attractive influence of our planet upon him.

And so the astonished multitude, who expected to see him cleaving with

mighty wings the blue empyreum, were shocked and dismayed to behold him

falling like some ordinary mortal earthward, unable, even with the aid of

all his familiar spirits, to escape the broken limb which the most

illiterate lord might have as easily gained, without bravado.

One cannot but admire the pluck

which led the Abbot to make this rash experiment, and the ingenuity with

which he explained his failure. "Many of the feathers," he wrote, "whereof

my wings were composed had been unwittingly taken from barnyard and

dunghill fowls. Hence the earth had more influence upon them since they

were unused to upward flight. Had they been eagles’ feathers then the

attraction of the heavens would have been as great as the attraction of

the earth was in other conditions." There is no record of his ever having

tried aviation afterwards.

For a considerable time the Castle

of Stirling was selected as the place of Coronation for the Scottish

rulers, and the fact of its being a favourite residence for royalty

brought it into notice as the birth-place of a succession of monarchs, and

it was also the scene of several tragedies connected with the royal

family. Some of the latter incidents may be briefly noticed here.

Alexander I., who reigned from 1106

till 1124 is the first Scottish King who is recorded as having died at

Stirling. William the Lion— 1165-1214——died at Stirling in his 71st year.

David, second son of Alexander III., born in 1273, died in Stirling Castle

in 1281, aged 8 years, and as his elder brother Alexander died in his

father’s life-time, the succession fell to Margaret, "the Maid of Norway,"

whose death in 1290 brought about the trouble with the claimants, in which

Edward I. of England interfered. While James I. was a prisoner in England,

his uncle Robert, Duke of Albany, was Governor from 1388 till 1420, in

which year he died at Stirling Castle. His son, Murdoch, became Governor,

but when James I. returned to his kingdom in 1424, he accused Murdoch of

treason, and caused him to be beheaded at Stirling Castle in the following

year, together with his son, his nephew, and his father-in-law. James IV.,

in 1488, when he was only 16 years of age, was brought from Stirling

Castle by the Lords, who had rebelled against his father, James III., and

was present at the Battle of Sauchie Burn, near Stirling, where the King

was assassinated. Alexander, Duke of Ross, sixth child of James IV., was

born in Stirling Castle, and died there in 1515 in his second year. Prince

James and Prince Arthur, sons of James V., both died in infancy at

Stirling Castle, in 1541, thus leaving the succession to the Throne open

to Mary, Queen of Scots, who was born in 1542, the year of her father’s

death. She was crowned in the Chapel at Stirling Castle in September 1543.

The year 1571 witnessed a series of tragic incidents. John Hamilton,

Archbishop of St Andrews, was accused as concerned in the murders of Henry

Darnley and also the Regent Moray, and was hanged at Stirling Castle. The

Regent Lennox, father of Darnley, was shot in a skirmish at Stirling; his

successor, the Regent Mar, died at Stirling Castle in 1572. James VI. was

baptized in the Chapel of Stirling Castle in 1566; and his beloved eldest

son, Prince Henry, was born in the Castle in 1593, but died in 1612 in his

19th year, and thus the King was succeeded by his second son and fourth

child, afterwards Charles I. These are all facts relating to the

connection of the Royal Family with Stirling Castle.

The Union of the Crown in 1603, when

the King and Court removed to London, had an important effect upon the

whole of Scotland, and especially on Stirling Castle. The place fell out

of notice for a considerable time, and until the great Marquess of

Montrose restored the renown of Scottish chivalry its existence was placid

and uneventful. The brilliant exploits of this famous commander brought

renown to Scotland; and during the century which followed, the position of

Stirling Castle as the key to the north by the east coast made it a scene

of continued turmoil and strife. Stirling Castle was captured and held for

a short time by the Covenanters. In 1651, after the defeat of General

Leslie and the Covenanters at Dunbar by Cromwell, the fugitive Scots made

Stirling Castle their rallying-place. This led General Monck to besiege

and reduce the Castle, and to carry off many of the national documents

that had been brought from Edinburgh as less secure than Stirling. It was

from the Castle in the same year that Charles II. set out upon his

invasion of England, which was terminated by the fatal Battle of

Worcester.

At the time of the Union of the

Parliaments in 1707 Stirling was one of the four Castles that were

specially described as the most important in Scotland. The first trial of

its strength occurred in 1715, when Argyll on his way to Sheriffmuir was

well-supported from the Castle. The next attempt on the Castle was in

1745-46, when the army under Prince Charles Edward was retreating

northward. The leaders of the Highland forces promised the Stirling people

would not be molested; but this pledge was not respected by the Jacobites,

and general plunder was the result. Preparations were made to besiege the

Castle; but the conflict at Falkirk, where the Prince was victorious, led

to the prolongation of the siege (against the will of Prince Charlie)

until the advance of the Duke of Cumberland’s army compelled a retreat

northward, which ended at Culloden. Since that time Stirling Castle has

remained unassailed.

James VI. was the last Scottish

Sovereign to live in residence at Stirling Castle. The Duke of of York

(afterwards James VIII. and II.) was here with his family for a short time

in 1685, amongst them being the daughter who became Queen Anne. In

September 1842, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert visited the place; and in

1859, the Prince of Wales (afterwards Edward VII.) examined the historic

Castle, so closely connected with the lives of his remote ancestors.

STIRLING CASTLE : ITS

PLACE IN SCOTTISH HISTORY. By Eric Stair-Kerr, M.A. Edin. and Oxon.,

F.S.A. Scot. Pp. viii, 219. With numerous Illustrations. Crown 8vo.

Glasgow : James MacLehose & Sons. 1913.

IN this volume Mr.

Stair-Kerr sets forth in a clear and attractive manner the events which

went to make Stirling Castle one of the great historic places of

Scotland. The story of Stirling Castle is in a great measure the history

of Scotland, and the author has been careful to avoid expanding his

volume into a national treatise, and has adhered closely to the

narrative of events that concern directly the ancient stronghold on the

rock. In the opening chapter the author takes passing but adequate

notice of the various associations, more or less mythical, which are

attached to Stirling by the early chroniclers. The castle definitely

comes into authentic history in the reign of Alexander I. (1107-1124),

who dedicated a chapel within its walls. Alexander died in Stirling

Castle, leaving the crown and a prosperous realm to his brother, David

I., who made the fortress one of his chief residences, many of his

charters being dated ' Striuelin.' During the period of national

prosperity that ensued Stirling did not take an important place, but in

the reign of William the Lion it emerged into prominence in sad and

humiliating circumstances. William, captured at Alnwick in 1174, was

confined by Henry II. of England in the Castle of Falaise, in Normandy.

After several months

conditions of peace were arranged, and William was set free upon signing

the Treaty of Falaise, by which he swore to be the vassal of the English

King, and agreed that the Castles of Roxburgh, Berwick, Edinburgh and

Stirling were to be garrisoned by English soldiers. This document was in

its effects one of the most far reaching that ever was penned. It gave

substantial grounds for the subsequent claims of the English Edwards to

the overlordship of Scotland, and was thus a prime cause of those

disastrous wars between Scotland and England which for four centuries

curbed the prosperity of England, and caused Scotland to be a backward,

poverty-stricken land, a prey to the attacks of foreign enemies from

without and to the spoliation of contending factions within. Not until

the eighteenth century was nearing its close did the last embers die out

of the fire which the unfortunate Treaty of Falaise helped to kindle.

Mr. Stair-Kerr's chapter

on the War of Independence shows the importance which was attached to

Stirling as a stronghold in those stirring times: it was the prize for

which Stirling Bridge and Bannockburn were fought. During the days of

the Stewarts, from Robert II. to Queen Mary, Stirling Castle was at its

zenith. Here the Court remained for long periods, the Palace, the

Parliament House and other buildings were erected as we know them now,

the Royal Gardens were laid out in great splendour by the old Tabyll

Round, below the Castle to the south, and the King's Park was the scene

of many a merry hunt. Tournaments and games, pageantries and morality

plays, dancing and music occupied the days and nights. Nor was the

tragic note awanting, as when the blood-stained Heading Hill witnessed

the execution of Duke Murdoch and his sons, or when James of the Fiery

Face plunged his dagger in Earl Douglas's body and flung the corpse out

of the window. Pathetic scenes there were, as when Queen Margaret,

holding the infant King by the hand, met the nobles at the gateway, and

rung down the portcullis ere from behind its bars she refused to

surrender the castle ; or as when Archibald Douglas of Kilspindie panted

up the hill beside the King as he rode to the castle, seeking, but

finding not, some kindly recognition from the set face of his sovereign.

Amusing incidents happened too, as when the French Abbot of Tungland

attempted, with a pair of wings of his own making, to fly from the

battlements, and fell among the refuse heaps of the Castlehill ; or when

the Gudeman o' Ballengeich sallied out on some of his unkinglike

adventures among his subjects. With the departure of James VI. for

England, in 1603, Stirling ceased to be a royal residence. It was still

a place of importance, however, so long as there was righting to be

done. It figured largely in Cromwell's campaign, and although Oliver got

no nearer than Torwood, his next in command, General Monk, besieged the

castle and forced its surrender. During the Jacobite troubles of 1715

and 1745 Stirling Castle again came into prominence, and with the

imprisonment and execution of Baird and Hardie, the Radical martyrs of

1820, the castle passes out of history.

There is a very

interesting chapter containing a comparison of the castle of Stirling

with those of Dumbarton and Edinburgh. Dumbarton was prominent as a

dwelling place of princes before the other castles emerged from the haze

of tradition, but the War of Independence brought the three strongholds

into line. All three were the scene of romantic exploits and heroic

feats of arms, and each was at one time or another the refuge of

sovereigns in distress. Dumbarton dropped earliest out of the stream of

national history, and Stirling and Edinburgh both became places of less

importance after the Union of the Crowns.

Mr. Stair-Kerr devotes to

the subject of Stirling Castle in poetry a chapter which we would like

to have seen expanded. It is a suggestive and fruitful theme, and if

prose writers had been included, more might have been made of it. The

author tells of the visits of Burns, Wordsworth, Scott; and it is to be

noted that it is chiefly as a haunt of visitors that Stirling figures in

literary history, at least after we have named the ballads, such as

Young Waiters and the references to the castle in Blind Harry, Barbour,

Dunbar, and Davie Lindsay. We have nothing but praise for the manner in

which Mr. Stair-Kerr has executed his task. The illustrations,

consisting of drawings of the old buildings of the castle by Mr. Hugh

Armstrong Cameron, are excellent, and include several taken from

original points of view. DAVID B. MORRIS.

You can download this book in

pdf format here |