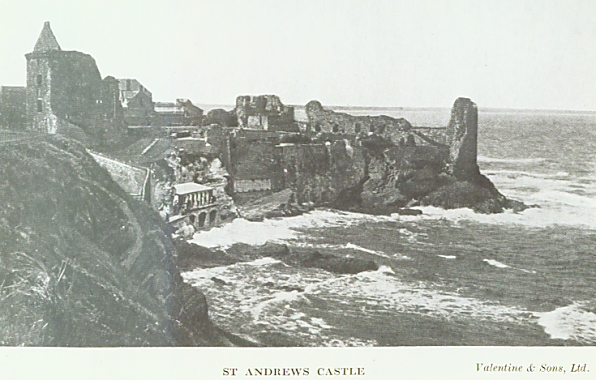

THE situation of St Andrews Castle

is exceedingly picturesque. The shore on each side of the ruins trends

inwards, leaving a projecting headland, upon whose rocky summit stand the

ruins of the Archiepiscopal Palace. The ceaseless beat of the wild North

Sea has swept away the ancient landmarks upon either side, gradually

leaving the foundation of the Castle to form an apex between two bays:-

"The peak on an

aerial promontory,

Whose caverned base with the vexed surge is hoary."

If this spot be really the site of

the original Castle of St Andrews, built by Bishop Roger in 1200, as there

is little reason to doubt, it savours more of romance than of practical

utility. For even though the encroachments of the sea have been great in

this locality they cannot have so seriously altered the position of the

Castle in little over seven centuries as to transform an inland fortress

into a sea-washed ruin. And, however conducive to reflection in a recluse,

it could not be altogether pleasant for men of the world, as many of the

Prelates were, to hear the "hollow-sounding and mysterious main" dashing

against the rock-bound coast, or watch it flinging its wintry spray

defiantly upon the topmost battlement.

Whether for resistance by sea or

land, no more commanding site could have been found along the coast than

that on which the Castle stands. Its peninsular position would enable its

possessor to sweep both the north and south coasts with ease; while the

approach from the land would be rendered difficult by the narrowness of

the passage. Local tradition tells of subterranean caves hollowed beneath

the foundations of the Castle, and represents the rock as honey-combed by

the action of the waves; and certainly there have been mysterious passages

recently discovered which may have been formed by extending such caves,

though their utility has not been satisfactorily explained.

But the ruin which now crowns the

rugged steep has not been reduced to its present state solely by the

ravages of time or of the elements. The resistless surge of human passion

and the fierce whirlwind of civil war have done more to render the Castle

of St Andrews roofless and uninhabitable than have the relentless storms

of many centuries. And though first erected a dwelling for• the men of

peace, it was not long ere the warriors of Scotland discovered that the

position which it occupied was too valuable to be sacrificed as a

Parsonage; even as they found that the site of Dunnottar Castle was too

important for a Parish Kirk. And thus it soon happened that the peaceful

abode of the Bishops of St Andrews became the residence of the fierce

soldiery both of England and France, whose lawless presence drew down upon

its innocent head the vengeance of their enemies. And the Castle, which

might have existed as long as the Vatican at Rome, had it been left to its

original possessors, did not continue for a century and a half without

suffering almost total demolition. Arising again from its ashes under the

benign influence of another Bishop, it re-asserted the proud position

which it had formerly held, and remained intact for another hundred and

fifty years. But the cloud of the Reformation had over-shadowed the

dignity of the priesthood, and "their gilded domes and their princely

halls" were now the abode of the leading spirits of the new birth.

Yet again was the ruined Castle

rebuilt and made habitable, but it was now shorn of all its former

greatness, and "Ichabod" was written on its ruins. And now, as if

"unwilling to outlive the good that did it," or wilfully refusing shelter

to the renegades from the faith of its founders, it stands bare and

desolate, a barren relic of the glory that passeth away. Only a few yards

from these ruins may be seen the burying ground where rest many of the

Lords Spiritual, who once held sway within its halls, mingling their dust

with that of the vassals whose toil supported them, and by whose labour

they were maintained. And as we pass from these tombs by the ever-sounding

sea to the melancholy ruin of former grandeur which the Castle presents,

we feel:-

"The sway

Of the vast stream of ages bear away

Our floating thoughts."

Here in the very birthplace of

Scottish Christianity we find the cradle of the Reformation, and this grim

ruin was the scene of many of the deeds of violence and of injustice and

lawlessness that called aloud for a new upheaval of Society—the avatar of

a Protestant Reformation. And now, as the moonlight breaks through the

unglazed window apertures, or falls shimmering, clear and cold, upon the

grass-grown courtyard, unroofed and open to the assaults of heaven, we

cannot escape from the romance of the situation—

"I wandered through the wreck of days

departed,

Far by the desolated shore, when even

O’er the still sea and jagged islets darted

The light of moonrise; in the northern heaven,

Among the clouds near the horizon driven,

The mountains lay, beneath one planet pale;

Around me broken tombs and columns riven

Looked vast in twilight, and the sorrowing gale

Waked in these ruins grey their everlasting wail!"

The action of the water upon the

free stone and shale forming the base of the Castle is apparent, though

the extent of this influence is much exaggerated. Some local historians

would have us believe that the angry surge has swept away towers and

turrets, walls and battlements, but there is more fancy than fact in their

statements. Yet there are many alterations in the formation of the Castle

grounds plainly discernible. At some remote period the whole of the

landward structure has been surrounded by a deep moat, presumably supplied

with tidal water and furnished with lock-gates communicating with the sea.

The debris of many years had accumulated within this fosse to such

an extent that it was level with the ground. But some years ago

excavations were made in the locality whereby the trench was quite cleaned

out, and a more correct view of the fortifications thus obtained. Amongst

other discoveries made, not the least interesting was that of the ancient

well in the courtyard, which has been cut out of the solid rock, and is

more than twenty feet deep to the water surface. In the North Sea Tower on

the north-west part of the courtyard, may be seen the Bottle Dungeon, a

cavity quarried in the freestone, twenty-five feet deep, with an aperture

forming the neck, seven feet in diameter and eight feet deep. Below this

point the dungeon expands to nearly seventeen feet in diameter; and as

there are no visible means of entrance, it is supposed that the prisoners

were incarcerated here by using rope and windlass to lower them into its

loathsome depths. The imaginative in-habitants of this neighbourhood have

peopled this fearful prison with many of the men familiar in history; but

the traditions connected with it are not very trustworthy. It is not

likely that the place was used except for purposes of temporary

confinement, and as an alternative to the rack or other form of torture.

The whole plan of the Castle is now clearly visible, and as steps have

been taken to preserve the ruins the ravages of time will no longer

prevail to overthrow it. The vicissitudes through which it has passed, and

which link it prominently with many notable events in Scottish story,

entitle the Castle of St Andrews to the tender regard and veneration of

the students alike of Church and of State History.

The exact date of the foundation of

the Bishopric of St Andrews is not now discoverable, but it is known to

have had a firmly established existence in the middle of the ninth

century. For a considerable period the history of the Bishopric is but a

succession of names and dates which, like the catalogue of the Pictish

Kings, is now of little interest to us. Early in the twelfth century

(about 1107) Bishop Turgot founded the Parish Kirk, and about fifty years

after, Bishop Arnold, the possessor alike of larger views and increased

revenue, began the erection of the splendid pile of St Andrews Cathedral,

whose ruins still testify to its former magnificence. Having thus provided

for the spiritual wants of their parishioners, it became advisable that

the Bishops should look after their own temporal welfare; and so Bishop

Roger laid the foundation of the Castle somewhere about the year 1200.

Hitherto the holders of the Episcopal See had resided either in the

ancient Monastery of the Culdees (now Kirkhill, where the foundations may

be seen) or in the house of the Prior, which adjoined the Cathedral

buildings. It no longer consorted with the dignity of so important a See

that the Bishops should have nowhere to lay their heads, and as the Royal,

as well as the Papal, favour had been bestowed upon them, they could well

afford to indulge in a habitation for themselves.

Old Andro Wyntoun, Prior of St

Serf’s on Loch Leven, in his "Cronykil," records that Bishop Roger was son

of the Earl of Leicester; but to this statement exception may be taken, as

it is not supported by other evidence. There certainly was a Roger de

Bellomont who fought at the Battle of Hastings in 1066, and whose

descendant was Earl of Leicester in 1128, but that Earl had no son called

Roger. This is Wyntoun’s account

"This Rogere

The Erle’s son was of Laycestere.

The Castell in his dayis he

Founded and gart biggit be

In Sanct Andrewys in that place

Where now that Castel biggit was."

The undertaking, though considerable

in those days, was but a trifle compared to the erection of the Cathedral

which was then proceeding; and it is extremely likely that the builders of

the latter edifice were employed upon Bishop Roger’s residence. The name

of the architect of these two buildings has not been discovered. At that

time Antwerp was the great school of masonry, and a travelling Guild of

Masons may have begun the structure which took many years to complete.

By whomsoever devised and executed,

the Castle was at length completed, and the Bishop would, no doubt,

prepare with devout gratitude for his "house-warming." One may picture the

venerable Bishop looking forward with hopeful eyes to a glorious future

for the bield he had now "biggit," and prophesying of the halcyon days of

universal peace which his firmly-founded Castle should never behold. Hope

still looks forward, in defiance of history and human experience, for the

brighter days that never come, and we delude ourselves by a faith in the

future for which our past gives no warrant. And thus runs the world away !

—

"Golden days, where are you?

Pilgrims east and west

Cry, if we could find you

We would pause and rest.

We would pause and rest a little

From our dark and dreary ways,

Golden days, where are you?

Golden days!"

Peace and prosperity were not long

the heritage of the Castle of St Andrews, for in those stirring times the

dignitaries of the Church were compelled to take an active part in the

affairs of State. As St Andrews was the foremost See in Scotland, both

because of its antiquity and extent, it was natural that the Bishop of so

important a diocese should be frequently brought to the front. And as

Glasgow bore the same relation to the west of Scotland as St Andrews did

to the east, the Bishops of these places were the leaders during the most

turbulent times. Foremost among these patriots was Robert Wiseheart (Wishart),

Bishop of Glasgow, in 1270, who was appointed one of the six Guardians of

Scotland on the death of Alexander III. in 1286, though he supported

Edward I. in 1290, but took up the cause of Robert Bruce in 1299, for

which Edward imprisoned him. Afterwards he joined Wallace with the

Scottish patriots, and officiated at the Coronation of Robert Bruce in

1306.. His faithful ally was William Lamberton, Bishop of St Andrews in

1297, who supported Wallace, though he had sworn fealty to Edward. He was

also present at the crowning of Bruce and was captured and put in prison

by Edward.

It was during Bishop Lamberton’s

time that the building of the Cathedral was completed, and he also

repaired the breaches in the walls of the Castle which Edward I. had

caused after Wallace had escaped from it. Having had it put in repair for

his occupancy, Edward I. and his Queen occupied the Castle from 14th March

to 5th April 1303-4, together with the Prince of Wales (afterwards Edward

II.), and to the Prince was committed by the King the stripping of the

lead from the roof of the Cathedral to make ammunition for the siege of

Stirling Castle. While Edward was in St Andrews Castle he received the

homage of the leading Scottish nobles and clergy.

The Castle was held by the English

till 1305, when it was captured and held by the Scots for a short period,

but was regained from them in 1306, and remained an English fortress till

1314, the year of the Battle of Bannockburn. These frequent attacks must

have seriously weakened the structure, for Bishop Lamberton, who died in

1328, found it necessary to spend his last years in the Priory instead of

the Castle.

Hardly had Lamberton been gathered

to his fathers ere the minions of Edward Balliol, son of King John

Balliol, and a dependant on the bounty of the King of England, Edward

III., seized upon the Castle, and forced the new Bishop, James de Bane, to

fly for refuge to Holland, where he died in 1332, leaving the See

unoccupied. Edward Balliol had invaded Scotland in this year, and won a

victory at the Battle of Dupplin, and he placed a garrison in St Andrews

Castle. The chief Scottish opponent of Balliol was Sir Andrew Moray of

Bothwell, son of the companion-in-arms of Wallace, who was proclaimed

Regent. Finding English soldiers in the Castle he attacked it and forced

them away; but finding that he had not men to spare for garrisoning it he

threw down some of the fortifications, and proceeded southward to expel

the invaders from Scottish soil. This incident is thus recorded by Andro

Wyntoun :—

"Sir Andro Murray cast it doun,

For there he fand a garrisoun

Of English men intill that place,

For the See than vacand was."

Ere another fifty years had gone the

Bishopric came into the hands of Walter Trail (1385-1401) a Prelate whose

influence in the affairs of the kingdom entitled him to rank as a true

patriot. During his term as Bishop the Castle was rebuilt and again made

fit for an episcopal residence. Yet, by a curious fatality, the princely

towers which he built became the prison-house of one of his dearest

friends, shortly after his decease. In the story of Rothesay Castle in

this volume, the sad tale of the murder of David, first Duke of Rothesay,

son of Robert III., by his unscrupulous uncle, the Regent Albany, was

narrated. Whilst this unfortunate Prince was supported by the counsel of

his mother, Queen Annabella, of his father-in-law, Earl Douglas, and of

his tutor, Bishop Trail, he withstood the insidious advances of his

ambitious uncle; but when death had removed all three of these

counsellors, the craft of the statesman proved too much for the

unsuspecting Prince. Rothesay was persuaded that after the death of the

Bishop it was his duty to occupy the Castle till a successor was

appointed. The young Duke made his way to Fife with a few followers, and

was waylaid by the emissaries of Albany near Strathtyrum and thrown into

prison at St Andrews Castle to await the instructions from his uncle.

Ultimately he was taken to Falkland Palace, where he met the sad fate

prepared for him. Thus the lordly dwelling which his old friend the Bishop

had erected, and where he would have been an honoured guest, became the

scene of his first imprisonment.

"What man that sees the ever-whirling

wheels

Of change the which all mortal things doth sway;

But that thereby doth find, and plainly feels

How mutability in them doth play

Her cruel sports to many men’s decay?"

The Castle of St Andrews increased

in importance as time rolled on, and soon had greatness thrust upon it.

Bishop Wardlaw had spent his forty years within its walls; and had done

much service to the world at large by founding the University, building

the Guard Bridge, and burning a few pestilent heretics "for the greater

glory of God." Bishop Kennedy had enjoyed his quarter-of-a-century there,

and signalized his reign by erecting the College and Chapel of St Salvator,

founding the Greyfriars Monastery, and endeavouring to introduce commerce

to the city by building a large vessel suitable for export trade. But the

venal period of the Bishops had arrived, and they were about to blossom

into Archbishops. Bishop Kennedy died in 1465, and his half-brother,

Patrick Graham, Bishop of Brechin, succeeded him in the following year.

Bishop Wardlaw, in 1440, had appointed John de Wemyss of Kilmany as

Constable of St Andrews Castle, so it had been kept in order during the

time of Bishop Kennedy. To his successor, Patrick Graham, belongs the

honour of being the first Archbishop of St Andrews, but he did not take up

his residence at the Castle in 1466, going to Rome for another purpose. In

1472 he returned with Bulls from Pope Sixtus IV., constituting St Andrews

the Metropolitan See of Scotland.

Despite the honour that Archbishop

Graham had brought to this country his life was a miserable one. He had

been impoverished by the bribes he had presented to the officials at Rome,

who had assisted him, and in 1478 William Schevez, then Archdeacon,

brought charges of heresy and simony against him, and he was deposed and

imprisoned, first in the Monastery of Inchcolm, and afterwards in Loch

Leven Castle, where he died, and was buried at St Serfs Isle. The

ambitious Schevez succeeded as second Archbishop, and apparently resided

at the Castle. Hardly had he been appointed than he dashed into a

controversy with Robert Blacader, Archbishop of Glasgow, on a point of

etiquette as to precedence. The dispute became so violent that it had to

be submitted to His Holiness Pope Innocent VIII., who evidently gave the

preference to St Andrews as the seat of the Primate. An ancient

Chartulary, still in existence, throws a sinister light on this

transaction. It shows that Schevez gave over the lands and Castle of

Gloom, on the Devon, and the Bishopshire on the Lomond Hills to the then

Earl of Argyll to bribe his support in the dispute with Glasgow. He thus

proves himself as the mediaeval ecclesiastic— solemn, precise,

exacting—anything but profound, whose interest lay more in vestments and

ceremonies than the welfare of the precious souls committed to his charge.

The Castle of St Andrews had now

gained additional importance as the seat of the Primate, and the

Archbishops took a prominent part in political affairs, and were

recognized as statesmen. So far back as the time of William the Lion, the

claim had been made, and since continued, that the King had the right of

presentation to this Archbishopric. Hence, when the See of St Andrews

became vacant through the death of James Stewart, second son of James Ill.

(1497-1503), James IV., who bore the same name as his younger brother,

exercised his right under peculiar circumstances. The King had then an

illegitimate son, Alexander Stewart, born in 1493, but not of age to be

made an Archbishop, so the See was left vacant till 1505, when he was

nominated. In that year Stewart went abroad; studied under Erasmus at

Padua, 1508; returned to Scotland in 1509 for his installation; was

appointed Chancellor of Scotland, 1510; accompanied his father the King in

1513 to Flodden, and fell on the battlefield, in his twentieth year.

A very curious complication arose at

Archbishop Stewart’s death. The Queen-Regent (Margaret Tudor, sister of

Henry VIII., and widow of James IV.), claimed the right of the Crown to

appoint the new Archbishop, and was prepared to select the famous Bishop

Elphinstone of Aberdeen, founder of Aberdeen (King’s College) University,

for the See of St Andrews; but he died at Edinburgh in October 1514,

before he could be installed. Meanwhile, in August 1514, Queen Margaret

had married Archibald Douglas, sixth Earl of Angus; and to please her new

husband she nominated the celebrated poet, Gawain Douglas, her uncle by

marriage, to the Archbishopric. But the Chapter of St Andrews elected in

preference John Hepburn, Prior of St Andrew, while the Pope recommended

Andrew Forman, Bishop of Moray for the position. There were thus three

claimants, proposed respectively by the Queen-Regent, the Chapter, and the

Pope, representing the Crown, the Church, and the Papal power.

Gawain Douglas, the translator of

Virgil, and one of the most learned and accomplished men of his time, made

the first move by taking violent possession of St Andrews Castle, having

the troops of Angus and the Queen-Regent to support him. The forces he had

at his disposal were lulled into a false security by the ease of their

conquest. Doubtless the new Archbishop, looking upon himself as the man in

possession prepared to enjoy his "lordly pleasure-house" with as little

apprehension of approaching danger as ever troubled the hero of his own

exquisite poem :—

"King Hart into his comely Castel

strang,

Closed about with craft and meikle ure,

So seemly was he set his folk amang

That he no doubt had of misadventure,

So proudly was he polished plain and pure,

With Youth heid and his lusty levis greeve,

So fair, so fresh, so likely to endure,

And also blyth as bird in summer schene."

But the dark-visaged Prior Hepburn

meanwhile was not idle. Silently assembling the fierce Border Clans of the

Hepburns and Homes, to whom he was related, he took the Castle by storm,

and turned out its occupants in disgrace. Chagrined by his defeat, the

Queen-Regent urged her husband, Angus, to besiege the Castle; but the bold

Prior, like a true Churchman Militant, set the forces of the Crown at

defiance. The combined efforts of the Royal troops and the Men of the

Means were unavailing to conquer the hardy Borderers, and the unscrupulous

Archbishop-elect for whom they fought.

Matters had thus reached a crisis,

and it seemed as though Scotland were to be blessed with three Primates.

The wily Bishop Forman, however, meddled less with arms than with men, and

he soon gained over the Earl of Home to his cause by the old-fashioned

method of bribery and corruption. Hepburn had no choice but to succumb to

circumstances. He withdrew his soldiers from the Castle and resigned all

claim to the Primacy on condition of receiving the Bishopric of Moray,

from which See his opponent Forman had been promoted, together with a

pension of three thousand crowns from the hinds of the Archbishop of St

Andrews, stipulating that no questions should be asked as to the revenues

which he had uplifted whilst in possession of the See. And thus the

presentees alike of the Queen-Regent and the Church were conquered by the

favourite of the Pope.

The ambition of the Queen-Regent

brought evil days upon her. When the Duke of Albany, grandson of James

II., and heft-presumptive to the Throne, was appointed Governor of

Scotland in 1515, he soon took vengeance upon those friends whom Margaret

Tudor had favoured.

The relatives of the Earl of Angus,

who were suspected, fell under Albany’s displeasure, and first among them

was Gawain Douglas. He was seized upon the pretext of some informality in

his presentation to the post of Bishop of Dunkeld, was carried to St

Andrews Castle and thrown into the Bottle Dungeon there in 1521, where the

vagaries of Fortune would give him food for regretful reflection, in the

darkness, upon the brief period when he was master in the Castle :—

"But yesterday I did declare

How that the time was soft and fair,

Come in as fresh as peacock’s feddar—

This day it stangis like ane eddar,

Concluding all in my contrair.

Yesterday fair upsprang the flowers—

This day they are all slain with showers;

And fowlis in forest that sang clear,

Now weepis with ane dreary chere,

Full cauld are baith their beds and bowers.

So next to Summer Winter bein;

Next after comfort caris keen;

Next to dark night the mirthful morrow;

Next after joy aye comis sorrow;

So is this warld and aye has been!"

By some obscure means Gawain Douglas

escaped from St Andrews in 1521, and fled to England, where Henry VIII.

was his patron; but he died there in the following year, of the plague,

aged forty-eight years.

Archbishop Forman died in 1522, and

was succeeded by James Beaton, then Archbishop of Glasgow. Beaten was the

son of John Beaten of Balfour, in Fife. He took his M.A. degree at St

Andrews University in 1492; was Abbot of Dunfermline in 1504; Lord

Treasurer, 1505-6.; Chancellor, 1513 to 1526; one of the Regents during

the minority of James V.; Bishop of Galloway and Archbishop of Glasgow,

1509; and Archbishop of St Andrews, 1523, continuing in that office till

his death in 1539. He kept lordly state within the Castle, and was

renowned for his hospitality, especially to French visitors to Scotland.

Beaton assisted James V. to throw off the yoke of his step-father, the

Earl of Angus, and in revenge Angus laid waste the Archbishop’s Castle of

St Andrews. Beaton, however, was a "building Prelate" even when in

Glasgow, and he soon restored his Castle to its former magnificence. James

V. was frequently entertained there, and it is possible that the King

would have made the Castle the residence of his first Queen, Magdalen de

Valois, in 1539, had he not built a special house in the Priory grounds

for her reception. It was during the rule of Archbishop James Beaton that

the persecution of the Scottish Protestants began, and in this work he was

especially active, utilizing the dungeons in the Castle for the

confinement of heretics. The Archbishop died in 1539, and was buried

before the High Altar in the Cathedral of St Andrews.

The successor to James Beaten was

his nephew, David Beaten, who was Archbishop from 1539 till 1546, when his

death was violently accomplished. He was the third son of John Beaten,

eldest brother of James Beaton, Archbishop of St Andrews, and was born in

1494; educated at St Andrews, Glasgow and Paris; Abbot of Arbroath, 1523;

Bishop of Mirepoix, in Languedoc, 1537; Cardinal of St Stephen in Monte

Coélio, by Pope Paul III., 1538; Co-Adjutor of St Andrews, 1538-39;

Archbishop of St Andrews, 1539.

The character of Cardinal Beaten has

puzzled many Scottish historians, their estimates being largely influenced

by religious prejudices on one side or the other. To imagine that he was

an empty and illiterate bigot is an open mistake. He was more of the

time-server who could perceive where the necessity had arrived for him to

bend to the blast, but who would strenuously hold fast that which he had

until a better appeared. Yet, however opportunist his actions might be, he

stoutly resisted the plans of Henry VIII. to conquer Scotland by capturing

the infant Queen Mary. When the game lay between the wily Cardinal and

bluff King Hal, it required skilful playing to come off victorious as

Beaten did. He was sent by James V. to arrange the King’s marriage with

Mary of Guise, which he accomplished successfully.

His uncle and predecessor, James

Beaton, as already mentioned, had taken up a violent attitude against the

Protestants, and the same policy was adopted and intensified by the

Cardinal, and it ultimately led to his destruction. The methods adopted by

him had made many enemies, but he pursued the persecution of the heretics,

as he accounted them, as if it were a pious duty. The tragic incident of

the Cardinal’s assassination has been so often narrated that it need not

here be detailed. The dastardly deed took place on Saturday, 29th May

1546, when Kirkaldy of Grange gave admittance by the drawbridge to the

Castle to Norman Leslie, Master of Rothes, John Leslie, his uncle, Peter

Carmichael, James Melvil, and others to the number of sixteen, who sought

out the Cardinal in his room, set upon him with swords and daggers, and

violently bereft him of life. They then, it is said, showed the dead body

at a window to the populace. The window usually shown to visitors was

certainly not the spot of this exposure, as it was erected by Archbishop

Hamilton, the Cardinal’s successor.

Assassination is one of the most

dangerous weapons that a struggling cause can adopt; and the deed, however

convenient for themselves, was loudly blamed by the Protestant party. So

far from rising into favour with their partizans, as the conspirators had

hoped, they found themselves almost universally execrated. Thus Sir David

Lyndsay, no friend to the Cardinal, and a most undoubted and faithful

Protestant, expresses his feelings:—

"As for the Cardinal—I grant

He was the man we weel could want,

And we’ll forget him soon!

And yet I think, the sooth to say,

Although the loon is well away,

The deed was foully done."

The assassins had taken possession

of the Castle, which was well-provisioned, and expected that their

sympathisers would have flocked to support them, and that they would hold

this fort till Henry VIII. had sent troops to capture Scotland and end the

Roman Catholic Church. In both expectations they were disappointed. Henry

VIII., the indomitable champion of Protestantism, died on 28th January

1546-47, and on 30th March following, Francis I. of France, the hero of

Romanism, "also died," so that both parties were deprived of their

leaders. The Castilians, as they called themselves, found that even the

Governor Arran had been the friend of the Cardinal, and they even sent an

humble petition to him that he would apply to the Court at Rome for a Bull

of Absolution to clear them of their crime. Well they knew that the

message to Rome would occupy some time, and meanwhile the English troops

might arrive to aid them. This was duplicity, but it was not worse than

that of the Governor, who certainly sent a message to Rome, as requested,

but took up the interval before the answer was returned in frantic appeals

to Francis I. to send skilful bombardiers to besiege St Andrews Castle.

Evidently both parties were insincere. The Castilians, meanwhile, had

received no inconsiderable additions to their numbers, amongst them the

indomitable John Knox, who had written that he recorded the murder of the

Cardinal "merrily," and who was yet to become a ruthless leader in the

demolition of the Churches of Scotland.

The Governor Arran, who had returned

to the Ancient Faith, found that his animated entreaties to the Court of

France had been effectual. He had besieged the Castle for four months

without victory; but at length the French soldiers and the artillery of

Leon Strozzi reduced the Castle to such a ruinous condition that the

Castilians capitulated in August 1547. And it is recorded by Lindsay of

Pitscottie that, "the French captain entered and spoiled the Castle very

vigorously; wherein they found great store of vivers, clothes, armour,

silver, and plate, which, with the captives, they carried away in their

galleys. The Governor, by the advice of the Council, demolished the

Castle, lest it should be a receptacle of rebels." In the "Diurnal of

Occur-rents," it is stated that the captors " tuke the auld and young

Lairds of Grange, Normand Leslie, the Laird of Pitmilly (Monypenny), Wm.

Henry Balnevis, and John Knox, with mony utheris, to the number of sex

score persones, and carryit thame all away to France; and tuke the spulzie

of the said Castell, quhilk was worth 100,000 pundis and tuke doun the

hous." It was this incident which called forth the current verse of the

time :—

"Priests, content ye noo;

Priests, content ye noo;

For Norman and his companie

Ha’e filled the galleys fou!"

The French Commander, Leon Strozzi,

had instructions to convey his Scottish prisoners to Paris, and the King

there decided that many of the Castilians should be incarcerated in

prisons at the north of France, the ringleaders, including John Knox,

should be sent to the galleys and chained to the oars. The bold spirits

who had put the Army of the Regent to defiance, were now treated as

malefactors, whose crimes were only short of receiving the extreme penalty

of the law. John Knox was imprisoned at Paris in 1548, and released in the

following year. He went to Dieppe, Geneva, where he met Calvin, and

Frankfort-on-Maine, reaching Scotland in 1556, and resuming his position

as a leader of the Scottish Reformation. His death took place at Edinburgh

in 1571, when in his sixty-sixth year.

The successor of Cardinal Beaten as

Archbishop of St Andrews was John Hamilton, an illegitimate son of James

Douglas, first Earl of Arran, and was born in 1511, was Abbot of Paisley,

and afterwards Bishop of Dunkeld in 1546, and was translated to St Andrews

in 1547 as Archbishop. The first work which he undertook was the repairing

of the ruinous Castle, and in this reconstruction he was probably assisted

by the masons whom he had employed to complete the building of St Mary’s

College. When the Reformers had gained power in Scotland in 1559, Hamilton

had to abandon the Castle, and from that time he was a fugitive until he

was captured at Stirling in April 1571, accused of complicity in Darnley’s

murder, and hanged ignominiously.

The Castle came into the possession

of the Protestants under the Regent Moray, and was used as a political

prison by him and his successors as Regents, becoming, indeed, "the

Bastile of Scotland." Though thus used as a secular prison, it was still a

portion of the ecclesiastical property, and James VI. did not feel

justified in annexing it without some process of law. This was not

accomplished for many years, and the place had become partly ruinous from

the repeated attacks made upon it by successive factions of the Scottish

nobles. At length the King made a bargain with George Gledstanes,

Episcopal Archbishop of St Andrews, as the representative of the ancient

Prelates, and in July 1600 a charter gave the Castle to George, Earl of

Dunbar, one of the King’s favourites. This arrangement, however, did not

last long, for when Episcopacy was fully established in 1612, the Castle

was given back to Gledstanes, and the Earl compensated. The new

Archbishops did not inhabit the Castle, but used it as an occasional

prison, and the place soon became ruinous.

About 1650 the Castle passed into

the hands of the Town Council, who shortly afterwards laid violent hands

upon the masonry, and used it for repairing the Pier. There is thus little

left even of Hamilton’s restorations. One may fancy the shade of good old

Bishop Roger addressing his successor, the Cardinal, in such lines as

these of the old Scottish poet Robert Henryson :—

"Thy kingdom and thy great empire,

Thy royalty nor rich array,

Shall not endure at thy desire,

But as the wind will wend away.

Thy gold and all thy goodis gay

When Fortune list, will from thee fall;

Sen thou sic sampills seest each day,

Obey and thank thy God for all!"