|

THE district of Beauly

possesses a peculiar charm for the Scottish tourist whose experience of

the scenery of Scotland has been confined to the Lowlands. The northern

portion of the kingdom is so radically different in character from the

southern that one might readily imagine that the Grampian Mountains formed

the boundary of a new State, or were the natural demarcation coinciding

with the artificial dividing line between two zones. The fertile vales of

Tweeddale and Clydesdale, with their inconsiderable mounts and hills, give

place, first of all to the varied uplands and elevated plains of

Perthshire, which are preparatory for the cloud-daring peaks of west

Aberdeenshire, and the rugged and barren mountains of Caithness and

Sutherland. Betwixt these extremes of verdant slopes and heath-clad hills

the district of Beauly lies; and whilst partaking of the nature of each,

it forms the connecting link between the two dissimilar aspects of nature.

The varied country is here

decidedly mountainous, and the waters which flow down the sides of the

hills are so concentrated and diverted into the gloomy glens which lie

between that they assume the dignity of rivers. The inland lochs which lie

embossed among the hills find their outlet to the sea through the straths

formed by the overhanging mountains; and though it is difficult to trace a

consecutive range of these, the phenomena which they display are similar

to those of the Grampians. The water-shed of the locality is east by

north, and many of the rivers join themselves together ere debouching into

the North Sea, the inward sweep of whose waters has hollowed out the vast

bay of the Moray Firth.

Three inland lochs at

different altitudes are driven by the set of the land to seek the same

outlet. Loch Affrick, after gathering the drainage of Glen Grivie, flows

into Loch Benevian through the romantic Strath Affrick. Issuing from the

latter loch, the overflow takes the name of River Glass, and assumes the

proportion of a considerable stream. Further north Loch Lingard becomes

tributary by pouring its waters through Strath Cannich into the Glass; and

beyond Scuir na Lappish, Loch Morar’s stream, rushing through the depths

of Strath Farrar, hastens also to join the swiftly-flowing Glass, which

becomes known as the Beauly river after receiving this accession. From

Struan Inn, the point of confluence of the Glass and Farrar, the traveller

may wander in any direction with the assurance of meeting with lovely and

picturesque scenery. He may pursue the precarious path which leads

westward to the shores of Loch Morar, following the devious course of the

Farrar, whose waters roll turbulently downwards to the ocean over rock and

fell, forming myriad cascades of silvery brightness which sparkle in the

summer sun, or dash impetuously down the strath, o’erladen with the spate

of winter snows; or, journeying south-westward, he may retrace the Glass

through all its windings until he reaches the point where Cannich joins

its stream. The road to the right will carry him to the still and silent

shores of Loch Lingard, whose waters lie enclosed by mighty mountains and

over-shadowed by lofty trees. But if he pursue the way which stretches

before him he will ere long reach the hidden recesses where Loch Benevian

and Loch Affrick form natural reservoirs to feed these rapid and

overflowing rivers. Despite the volume of water which flows through the

channel of the Affrick, the inequalities of the rocky way which it follows

break it up into innumerable waterfalls of little altitude, but of great

force and energy. And when Mamsoul and Beinattow, the presiding mountains

which rule the Cannich and the Affrick, are capped with snow, and the

wintry torrents are rushing down their precipitous sides, the picturesque

effect which these rivers present is striking and impressive.

The fringe of the great

Caledonian Forest, which once stretched from the Firth of Forth to the

Banks o’ Dee, here still retains a portion of its primeval grandeur, and

gigantic birch trees and towering, pyramidal firs cast their sombre

shadows over the restless stream which brawls below.

"From the sources which well

In the tarn or the fell,

From its fountains

In the mountains,

Its rills and its gills,

Through moss and through brake

It runs and it creeps

For a while till it sleeps

In its own little lake.

Here it comes sparkling,

And there it lies darkling,

Now smoking and frothing

Its tumult and wrath in,

Till in this rapid race on which it is bent

It reaches the place of its steep descent."

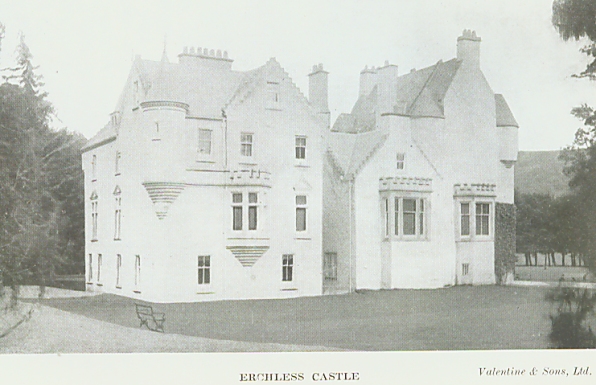

Amid such scenery thus

imperfectly described stands the old Castle of Erchiess, the seat of the

head of the old Clan Chisholm. A short distance from Struy Bridge, on the

banks of the Beauly formed by the conjoined rivers of Farrar and Glass,

and pleasantly situated upon a wooded eminence overlooking the stream,

this Castle adds that element of human interest to the scene without which

it would be incomplete. The many-gabled structure, with its quaint turrets

and hidden turnpike stairs, might well afford to the student of

architecture a compendious history of his art. The original Castle,

judging from its plan, was erected early in the 14th century, though there

have been many alterations on the structure since that time.

The oriel windows, elegant

as they may be, formed no portion of the original building; nor can one

believe that the chief who laid the foundation stone in remote times ever

crossed the threshold of his dwelling beneath a pillared portico. But

these adjuncts, since they are so plainly additions and not

restorations, add to the piquancy of the general effect. In any case

it would be difficult to find another site for a Scottish Castle at once

so picturesque and so commanding.

The Chisholms belonged

originally to the Border Counties, the earliest noted in history being

John de Chisholme, who is named in a Bull of 1254 by Pope Alexander IV.

John’s grandson, Sir John de Chisholme of Berwick, fought at Bannockburn

in 1314, on the side of Robert the Bruce. About 1403, Alexander de

Chisholme, of Chisholme, Roxburghshire, who was the son of Sir Robert,

Constable of Urquhart Castle and Sheriff of Inverness, was married to

Margaret, who is described as "the Lady of Erchless," and this seems to

have been the earliest of the Chisholms of Erchless Castle. The lands in

the possession of the family at this date were Strathglass and Ard, and

later they came into the estate of Comar, which made them proprietors of a

large part of Ross-shire.

In 1685, when the Duke of

York became James II. and VII., many of the Highland Clans adhered to his

cause, as they were chiefly adherents of the Romish Church, and expected

the restoration of the ancient faith. The fatal conflict at the Pass of

Killiecrankie, where Viscount Dundee fell in the hour of victory, forced

the Northern Clans to retire, pursued by the Scottish Whigs and English

Army. John Chisholm garrisoned Erchless Castle to resist the pursuers, but

he had at length to surrender it to General Livingstone (afterwards

Viscount Teviot) who was Commander-in-chief of the Scottish forces of

William of Orange.

With that blind devotion to

the Stewart Cause which is one of the problems of Scottish history at the

time, Roderick Chisholm, son of John, took part in the Jacobite Rising of

1715, in support of the Chevalier de St. George (James VIII.) after his

services had been foolishly refused by George I. The estates of Roderick

were forfeited, but he was afterwards pardoned in 1735, and the lands

restored to him. This did not prevent him from joining Prince Charles

Edward in 1745, and leading eighty of the Chisholms through the campaign

till Culloden, where thirty of them were killed and his son of the same

name also fell. The lands were not alienated at this time, and have

remained with his descendants ever since in undisturbed possession.

Erchless Castle, though

thus intimately associated with war, has also a traditional romance of

love, the story of which is still current in the locality, though dates

are lacking. About six miles from the Castle, on the other side of the

Beauly River, stands the Castle of Beaufort, the ancient seat of the Clan

Fraser. It so happened at one time that Fraser, the Lord of Lovat, had an

only daughter whose welfare was his chief concern. Reared beneath the

shelter of Beaufort Castle and encircled by the unremitting care of her

father and brethren, she grew up to womanhood. The young Chief of the

Chisholms had seen the maid and had fallen captive to her charms; but the

two families were then at feud, and though the lady reciprocated his

affection no marriage seemed possible. At length Chisholm decided to win

his bride at the point of the sword; and one moonlight night, accompanied

by a few of his faithful followers, he waylaid her near some well-known

trysting-place and bore her away to his own territory. With commendable

caution he refrained from carrying her to Erchless Castle, where she would

be first sought for, but rather took her to a lonely isle in Loch Bruirach

where he deemed her safe from discovery.

Meanwhile the Frasers had found out the

loss of their young lady, and the baron rose up in wrath and ordered a

speedy pursuit :—

"O fy!

gar ride, an’ fy! gar rin,

An’ hasteye, bring these faitours

again,

For she’s be brent an’ he’s be slain."

The artifice of Chisholm in conveying his

love to the retreat he had chosen was of no avail. The Frasers had

mustered in force and the Chisholms could not withstand them.

"From

Beauly’s wild and woodland glen

How proudly Lovat’s banners soar;

How fierce the plaided

Highland clan

Rush onward with the braid claymore."

They soon discovered the

spot which the youthful lover had chosen. What will not man endure when

love and beauty is his reward? But the odds against The Chisholm were

fearful; and when his lady clung to his arm and implored him to resign her

again to her kindred rather than risk his life, her very entreaties

impeded his swordsmanship. With his left arm supporting her whom he valued

as dearer than life, he strove to beat back the weapons of his enemies;

and though his defence was a gallant one, of what avail was his prowess

against so many? Had he remained on the mainland some fleet horse might

have borne him into the wilds of Glen Elchaig or the barren shelter of

Mealfourvounie; but the dark waters of the loch encircled him. Bearing up

his precious charge he again essayed the combat, even though overborne by

his assailants, but the moon was overcast by a flying scud which swept

across the sky, and in the temporary darkness which was thus produced the

fatal thrust which was aimed at his heart by one of her brethren was

received by herself! Sinking breathless, lifeless to the ground, the fair

cause of this deadly tumult yielded up her breath, and lay before the

speechless and agonized combatants in the chill embrace of Death! Who

shall dare intrude with officious description on such a scene as this, or

strive with laboured words to explain the depth of such heart-misery? Only

the simple language of the ballad which describes a similar situation can

express the profound emotions of such an incident:-

"I wish l were where Helen

lies!

Night and day on me she cries,

And

I am weary of the skies

For her sake that died for me!" |