|

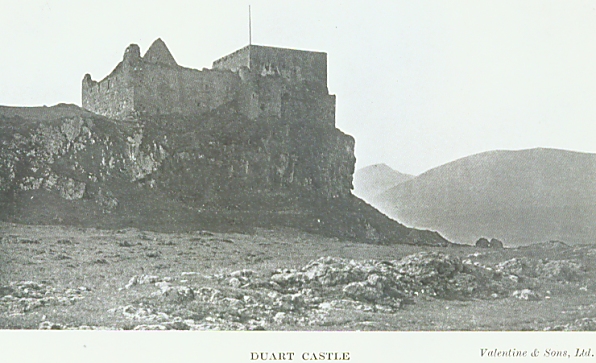

THE tourist who takes

shipping at Oban with the intention of passing through the Sound of Mull

cannot fail to observe the picturesque ruins of Castle Duart, which stand

on a promontory of the island of Mull, immediately opposite Lismore. The

situation occupied by these remains exhibits the chief characteristics of

Highland maritime scenery, and would be worthy of attention even were

there no historical memories connected with it. The Point of Duart has

been formed by the wash of the Atlantic Ocean rushing through the Sound of

Mull, and the rugged peak which it exposes to the confined course of this

current diverts its energy northwards to the indented shores of Loch

Linnhe, to the coast of Morven, and to the islets around Lismore. The

channel between this point and the nearest land is about four miles wide;

and as the Castle is exposed to all the fury of the northern gales which

swoop down upon it from Loch Linnhe, the wildness of the surrounding

scenery may be easily imagined. The hundred peaks of Argyllshire stand out

boldly against the horizon, while the shore on either side of the Sound of

Mull is dotted with the remains of ancient Keeps and Castles, the relics

of the stern feudal system which once obtained in the district, the

deserted strongholds of some of the Highland Clans that are now scattered

throughout the wide world. And as the rude rocks which line the shores

tell the story to him who can read aright of volcanic upheavals and

commotions which have altered the face of Nature in pre-historic times, so

these silent ruins speak eloquently of fierce revolutions in the history

of man, and, like enduring monuments, indicate the progress and

development of civilization. They tell of times :—

"When sullen Ignorance

her flag displayed,

And Rapine and Revenge her voice obeyed."

But they also show by the

very helplessness of their condition that the days of their years are

fled, and their former glory has departed. The races which have compelled

a subsistence from these barren hills, or wrested their means of support

from the raging sea, have vanished from this scene, and left little behind

them save the names which may be preserved in history, and the desolate

ruins which become the wonder of succeeding generations :—

"All ruined and wild

is their roofless abode,

And lonely the dark raven’s sheltering tree;

And travelled by few is the grass-covered road

Where the hunter of deer and the warrior trode

To his hills that encircle the sea."

Amongst the Clans which

formerly inhabited this quarter none was more famous than that of the

Macleans, whose feudal stronghold was Castle Duart. By personal prowess

they had extended their possessions, and by judicious intermarriages they

had increased their power, until there were few amongst the western chiefs

that could compete with them. And as every Highlander inherits the notion

that his Clan was designed by Providence to lead all others, it was

natural that the Macleans should be at feud with those who were not their

vassals and inferiors. The situation of their Castle was peculiarly

favourable for the development of their ambitions hopes, and they soon

found that there were no "foemen worthy of their steel" in the whole

island of Mull.

These marriage connections,

however skilfully devised, sometimes brought the Macleans into serious

difficulties. Their relations with the Clan Campbell, for instance, were

at once put upon a war-footing by the brutal conduct of Lachlan Maclean

towards his wife, a daughter of the Earl of Argyll, which true story is

narrated further on in this notice as connected with the Lady’s Rock,

which stands about midway in the channel between Duart Point and Lismore.

It is impossible to give an

accurate date for the erection of the oldest part of Duart Castle. There

probably was an original Keep on the site of the present Castle, a portion

of which, still in existence, has been adopted in the later erection. This

part has high and massive walls, varying from 10 to 15 feet thick, which

enclose what is now the courtyard. The Castle was probably founded by

Lauchlan Maclean, surnamed Lubanach, about the year 1366, in which year he

married Margaret, daughter of MacDonald, first Lord of the Isles. As

Maclean of Duart, he and his successors for a long time were heritable

Keepers of many Castles in the district, and had many possessions both on

the mainland and in the Western Isles. The first reference to the Castle

in documents is dated 1392, but the building was not completely finished

till the time of Hector Mor Maclean, about 1560, and this Chief also

married Mary, daughter of Alexander Macdonald, then Lord of the Isles,

whose seat was at Isla. From a comparison of the architecture of different

parts of the Castle, it appears that the Great Tower was erected by this

Hector Mor Maclean.

The MacDonalds had made

common cause with. the Macleans against the rising power of the Campbells

of Argyll, but their alliance was short-lived. The Chief of the

MacDonald’s had formed an expedition along with Maclean of Duart, and they

had ravaged some of the richest territories belonging to the Campbells.

But the son of the Chief of the MacDonalds afterwards married a daughter

of the second Earl of Argyll, and he thus became the enemy of Maclean. A

curious complication arose later, when Sir Lachlan Mor Maclean sought to

end the contest with the Campbells by wedding Lady Elizabeth Campbell,

another of the daughters of the second Earl of Argyll, and sister of the

third Earl.

The ambition of Maclean was

unbounded, and though his alliance with the House of Argyll ensured to him

the peaceable possession of his heritage, he was not content with it. When

Sir Donald MacDonald of Lochalsh sought to have himself proclaimed as Lord

of the Isles, Maclean threw up his connection with his brother-in-law

Argyll, and against the latter’s advice, he stirred up an insurrection in

the Hebrides. The powerful influence of Colin, third Earl of Argyll, whose

first duty after his accession was to take up arms against his relative

Maclean, at length quelled the turmoil. Maclean, however, seems never to

have forgiven Argyll for his share in the affair, and determined to wreak

his vengeance upon his own wife. History is not very clear as to the

character of Lady Elizabeth; for whilst one account makes her to appear

almost in the light of a martyred saint, the other asserts that she had

twice attempted to take away her husband’s life. On thing is certain—that

the misfortune of barrenness was magnified into a crime by the lawless

Highland Chief, and he determined to effect her destruction.

The method which he adopted

exhibited the refinement of savage cruelty. Off the coast of Mull, as

already explained, there is still shown the bare and solitary rock which

her lord determined should make her pathway to heaven. Fringed with

sea-weed, and ever moist with the lapping waters which cover the surface

entirely at flood-tide, this lone rock might well scare the high-born

lady, whose brutal husband led her here to endure the agonies of a slow

and torturing death. One may imagine the fearful forebodings of the Lady

Elizabeth as the advancing waters by their resistless march bore her

nearer and nearer to her doom. At length, when despair had all but seized

her, she noticed a little boat upon the waters, whose occupants replied to

her frantic signals of distress. They drew near, and to her infinite joy

she beheld the faces of some of her own clansmen, whom Providence had sent

to her rescue when in extremity. They bore her swiftly away to her

brother’s house, and restored her, weeping, to the shade of the paternal

roof-tree.

The Campbells arose in a

body to demand retribution, but the politic Earl did not care to press his

brother-in-law too severely. The task of revenge fell therefore upon Sir

John Campbell of Cawdor, whose courage kept pace with his impetuosity. Not

long after, having heard that Maclean was in Edinburgh, Campbell hastened

there, entered his lodgings, and slew him as he lay in bed, scorning to

give him even the privilege of defence, since his intended murder of his

wife had disgraced him as a Knight. As might have been foreseen, this rash

deed at once drove the two clans to arms, and only the interposition of

the Government prevented much useless bloodshed. Upon this strange story

Thomas Campbell, the poet, founded his poem of "Glenara." which, though

sacrificing facts for the sake of the poetry, is substantially correct

I dreamed

of my lady, I dreamed of her grief,

I dreamed that her lord was a

barbarous Chief;

On a rock of the ocean fair Ellen did seem—

Glenara! Glenara! now read me my dream!’

In dust low the traitor has knelt on

the ground;

And the desert revealed where the lady was found;

From a rock of the ocean that beauty is borne;

Now joy to the house of fair Ellen of Lorn!"

Joanna Baillie made this

story the subject of one of her "Plays of Passion," under the title of "A

Family Legend," but used some poetic licence as to the details. The facts

as recorded above are beyond dispute. |