|

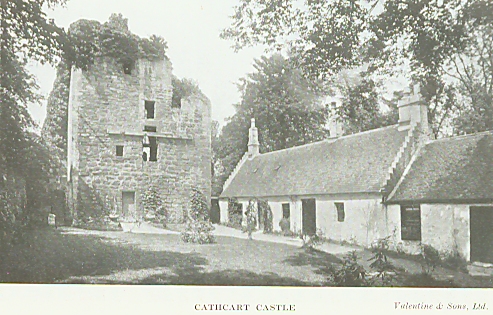

It is worthy of note that,

whilst Crookston Castle witnessed the earlier and happier portion of

Mary’s variegated life, Cathcart Castle, which is all but visible from it,

was the scene of her final downfall. The latter stands about seven miles

from Crookston, and nearly two miles south-east of Glasgow, upon the

Mearns Road. An inconsiderable pathway which leaves the main road a short

space beyond the bridge over the Cart, leads past the Castle gate, which

is not surrounded now by any vestige of garden ground. Unlike Crookston,

it must have afforded little advantage to its inmates in the matter of

defence. it is easily approached on all sides, and is more like a

pleasure-palace than a stronghold. There are arrow-slits m the walls, and

the appearance of an attempt at fortification; but the surrounding

locality affords too easy access for this to have been of much avail. Yet

the outlook from one of the windows in the upper chamber, still called

Queen Mary’s Window, is very lovely. The ground upon which the Castle

stands slopes gently down to the river’s brink, whose silver sheen

glimmers faintly here and there amid the overhanging boughs of birch and

ash and nodding beech. Due north from this point of view lies the field of

Langside, where was fought the final and decisive conflict which

terminated Queen Mary’s career in Scotland.

The lands of Cathcart

belonged in the 12th century to a family bearing that name, and so

continued till 1546, when the Sempill family acquired them through

marriage. The original Cathcart family was represented in 1740 by the

eighth Baron, who repurchased the ancestral property. The Castle, which

had been built in the 15th century, was partly demolished by this Baron

Cathcart, and has not since been occupied. In 1814 the tenth Baron was

created. Earl Cathcart, and the members of the family have long been

distinguished in military history; Cathcart House, which took the place of

the old Castle, was built by Mr James Hill, Solicitor, Glasgow, who

acquired part of the estate in 1788, and from him it passed, in 1801, to

Earl Cathcart, when the rest of the estate was purchased by him.

The undulating lea, now

called "Battlefield," is completely commanded from "Queen Mary’s Window,"

and it was doubtless from here that the hapless Queen watched with

breathless interest the contest upon which her own future depended. After

her daring and romantic escape from Lochleven, she made her way to the

east coast so as to mislead her pursuers; then doubling back, she sought

to reach Dumbarton Castle, which was then held by her partisans. Taking

the road by Hamilton, she was soon joined by many of the Lowland gentry,

with their retainers, and found herself at the head of a small but

well-appointed army. Fearful of risking a conflict with her hall-brother,

the Regent Moray, who then lay with his troops at Glasgow, she took the

south bank of the Clyde, intending to cross to the Dumbarton side when

safe from interruption. But the intelligence which Moray had received of

her movements enabled him to checkmate her plans. Detaching a strong body

of his troops he occupied the field at Langside, which lay directly on her

line of march, thus leaving her no option save either to dare the battle

or fall helplessly into an ambuscade betwixt the two portions of his army.

The confidence of the Queen in her cause decided her to adopt the former

course, and in a fatal hour for her the armies engaged in deadly conflict.

The position of Cathcart Castle, which overlooked the field of battle,

afforded the most favourable spot from which to observe the course of the

strife, although, from its proximity to the combatants, perhaps not the

safest place for so precious a prize.

That she occupied Crookston

Castle for this purpose is not a reasonable supposition, since its

distance from Langside and its situation would effectually prevent her

from obtaining early intelligence of the course of the battle. And her

flight to Dundrennan Abbey after the disastrous issue of the conflict was

much more easily accomplished from Cathcart than from Crookston. Yet one

must remember that so weighty an authority as Sir Walter Scott mentions

the latter place as the position which she held, though perhaps the

romantic and poetical contrast between her earlier and later days at

Crookston might influence the poet to adopt this theory even though not

supported by facts. One thing is certain, that local tradition ascribes

this melancholy interest to Cathcart, and even points out the particular

spot where the ill-fated Queen beheld the overthrow of all her hopes. And

thus, by a curious combination of circumstances, two Castles standing upon

the banks of the same river, Cart, and separated by but a few miles from

each other, serve as landmarks, tear-fraught and sad, recording the joys

and sorrows of Scotland’s fairest Queen—her time of love and her time of

war. |