|

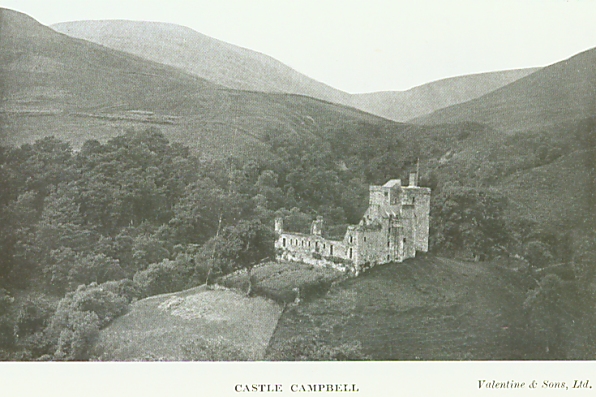

Picture of Castle Campbell sent in by Louise McGilviray

THE Ochil Hills bear much the same relation to the East

Coast of Scotland as the Kilpatrick Hills do to the West. Though not in

themselves privileged to give rise to an extensive stream, they are both

inseparably associated with the noble rivers, the Forth and the Clyde,

which sweep majestically past their several bases on their way to the

eastern and western seas. But in point of grandeur the Ochils transcend

the western range, even as they are themselves dwarfed into insignificance

by the loftier hills of the north.

Opposed by the Pentland

Hills, which limit the southern basin of the Forth, the Ochils form a

lofty barrier between the valleys of the Forth and the Tay, and send

tributary streams to swell the volume of both of these rivers. Three minor

ranges of the Sidlaws, the Ochils, and the Pentland Hills thus enclose

between them the two noblest rivers on the East Coast of Scotland, and

direct their course to the North Sea. The Ochils, unlike the more northern

mountains, are clad with verdure almost to their summits, and though bold

in outline and varied in colour, they have not the sterile majesty of the

peaks of Aberdeenshire. At their base lie many little hamlets and towns,

whose subsistence is drawn rather from their manufactures than from

agriculture. Tillicoultry and Alva are alike famous for their productions

in the woollen trade, and the extensive factories which here exist show

that the introduction of steam as a motive power has rather increased than

diminished the number of weavers.

Pre-eminent among the Ochil

towns stands Dollar, picturesquely situated upon one of the innumerable

"crooks of Devon," which claims remembrance from many causes. The

educationalist will think of it as the site of the famous Academy, to

which many Scottish men of letters owe their mental birth; the poet will

remember it as the residence of Tennant, the inimitable author of "Anster

Fair," and the immortalizer of "Maggie Lauder"; and the Waltonian will

never forget that in its neighbourhood he has bagged the finest trout

which the streams of Scotland afford. For down by the very doors of the

inhabitants of Dollar flows the lovely river Devon, whose name is not

unknown among the lyrics of Scotland, since of it does our National Bard

sing in his well-known lay:-

"Row pleasant the banks of

the clear winding Devon,

With green spreading bushes and

flowers

blooming fair."

It is not easy to find a

more purely Scottish stream than this same Devon river, which calls forth

the enthusiasm of the tourist. Taking its rise in the eastern end of the

Ochil range, it wanders by the natural dip of the land towards

Lochleven; but a peculiar geological

formation interposes a barrier and diverts the stream westward, so that,

instead of having a short-lived existence ere it lost itself in the loch,

it "meandering flows" through many miles of varied scenery, until at

length it becomes tributary to the Forth. Nowhere does it attain

considerable size, but everywhere it presents the essential phenomena of

the Scottish stream. From the Crook of Devon, which is literally the

turning-point of its existence, it wanders placidly between the banks with

verdure crowned, until it nears Rumbling Bridge.

Here the rapid descent of

the valley of Dollar causes it to assume a more turbulent character, and,

dashing through the "Devil’s Mill," where its stream is not seen, but

heard as some weird subterranean "voice of many waters," it hurries on

towards the Cauldron Linn. The force of the water, continuously rushing

for centuries, has hollowed a vast basin in the sandstone rock, and the

stream now pours through a contracted aperture, with the force of a

water-spout, sheer over the precipice. From this point it descends more

gently through the valley of Dollar, presenting all the characteristics of

a Scottish salmon-stream, and realizing Tennyson’s description of "The

Brook" :—

"I wind about, and in and

out,

With here a blossom sailing,

And here and there a lusty trout,

And here and there a grayling."

Passing near the town of

Dollar, it takes a south-westerly direction toward the Forth, merely

catching a glimpse of the picturesque Castle Campbell, which stands amid

the green woodland of the hill.

Viewed from a distance,

this ancient Keep might readily be mistaken for some retiring

mansion-house, embowered in a miniature forest of larch and beech, or, by

a stretch of the imagination, to the poet’s mind it might seem

"A palace,

lifting in eternal summer

Its marble head from out a glossy bower

of leaves."

Yet a nearer acquaintance

with its topography will speedily

dispel this illusion. The approach to the Castle soon alters from the mild

riverside way with which it begins, to the rugged and stern mountain path

which terminates at the ruin. The "bower of leaves" becomes a gloomy

forest, and the "marble palace" vanishes into a grim and solitary ruin,

which frowns defiantly from the summit of a precipice, apparently

in-accessible. The road is now narrowed to its minutest limit, and crosses

the fearful chasm which partly surrounds the Castle by one of those shaky

wooden bridges which terrify the soul of the timorous tourist. But the

view to be obtained from this spot is well worth the

trouble thus occasioned. In the valley of the Devon its glistening stream

appears, disappears, and reappears far below the spectator; and the spires

of Dollar and the factories of

Tillicoultry, the scenes of the triumph of head and hand, are at once

visible. Over the rising ground which lies between the Devon and Alloa,

the estuary of the Forth may be seen, now expanded into a noble firth;

while westward the levelling country indicates, the proximity of the

fertile Carse of Stirling.

Nearer the point of vision

the two streams which flow around the Castle and fall into the Devon a

short way from it have been named by some romantic native in pre-historic

times, the Water of Care and the Burn of Greif (Gryfe); while the ancient

title of the ruin itself was "the Castle of Gloom," and the site of the

melancholy trio was "the Valley of Dolour." This poetical combination,

however, like so many fanciful tales, has collapsed before the searching

examination of this practical age, and a new interpretation must now be

given. The name of Castle Gloom is probably a corruption of the Gaelic

Chleum or (loch Leum—the Mad Leap, though the origin of that

title is lost in obscurity. The Water of Care was most likely applied to

the stream after the building of the edifice, as it seems an easy

transition from Caer, the Celtic prefix for a castle and its

surroundings. Dollar is now supposed to have been originally Balor,

the high field—a title which its position justifies; and thus the tender

element of romance evaporates beneath analysis.

The date of the erection of

the Castle is now undiscoverable, nor has the most elaborate investigation

thrown much light upon its origin. There is a tradition still current

which declares that it was a portion of the dowry which King Robert the

Bruce bestowed upon his sister, Lady Mary Bruce, on the occasion of her

marriage with Sir Neil Campbell of Lochow. But if this was the case it

must have gone out of the possession of the family afterwards, for it was

certainly held by Archbishop Schevet, of St Andrews, and was gifted by him

to the head of the Campbells in his tithe as a bribe to secure his support

on a special occasion. The Archbishop died in 1498 at an advanced age. In

1493 an Act of Parliament was passed to enable the proprietor (apparently

the second Earl of Argyll) to change its name from "Castle of Gleume" to

"Castle Campbell," by which designation it is still known. And though it

must have been peculiarly convenient for a powerful western clan to have a

stronghold of such security in the eastern district, whereby disaffection

might be overawed, the isolation of the Castle from the main body of the

Clan Campbell frequently exposed it to danger, and finally brought about

its destruction.

The rivalry between the

clans of the east and the west of Scotland raged with violence for

centuries, and the untutored clansmen pursued their feuds with the same

deep spirit of revenge as a Corsican follows the vendetta of his family.

When, therefore, the Covenanters in the time of Charles I. included two

such eminent men as Montrose and Argyll, the leaders of the Grahams and

the Campbells, who had been sworn foes for a lengthened period, it was

soon evident that they could not long remain devoted to the same cause.

Their traditional enmity effectually prevented them from coalescing, and

the crafty spirit of Argyll led him to attempt

"Ways that are dark,

And tricks that are vain,"

The haughty soul of

Montrose recoiled from his leadership and renounced the Covenanting cause

which he had espoused. His overtures to the King were well received at

Court, for his reputation as a warrior had gone before him, and he was

looked upon as a Chevalier Bayard,

sans peur et sans reproche.

The exploits of the great

Marquess of Montrose in Scotland read more like a romance of olden times

than veritable history; and his heartfelt devotion to the King in good or

ill-fortune elevate him to the position of a hero. But the sun of the

Stewart family was then under eclipse; and it was not given to Montrose to

be the instrument of their restoration to power, however strenuous his

endeavours for that purpose; though, perhaps his cruel and ignominious

death did as much to forward the Royal Cause as his most brilliant victory

on the field of battle. The history of Montrose, however, is not to

concern us at present, save in its relation to Castle Campbell.

The period of Scottish

history which treats of the Civil War during the time of Charles I. and

the Commonwealth, shows distinctly that the gratification of private

revenge and the settlement of family feuds largely influenced the

combatants. The wavering fortunes which inclined now to the Covenanters

and anon to the Royalists soon reduced the land to the state in which

Judæa was placed when "there was no King in Israel." Argyll had his own

traditional enemies, but so also had every prominent man in his retinue;

and thus vengeance was widely spread, and never lacked opportunity. The

history of the time was a constant record of murder and rapine, of insult

and reprisal, until the condition of the country became absolutely

deplorable. The opposing forces soon reached that stage at which no sense

of honour restrains from excess, and when the claims of family ties and

blood relationships are boldly set at naught or publicly outraged. And it

was during this fearful time, and as a result of this melancholy and

fratricidal position that Castle Campbell fell a victim to the general

fury.

The Campbells, as already

mentioned, were at feud with the Grahams, but they were also sworn foes to

the Ogilvies, another powerful eastern clan, which commanded a large

portion of Forfarshire. The Earl of Airlie, leader of this clan and a

devoted adherent of Charles I., had removed to England early in the

struggle of 1640, fearing that the Covenanters would insist upon his

signature. His Castles of Airlie and Forter were left in charge of his

son, Lord Ogilvy, and as they were well-garrisoned, he thought they might

escape the rage of the enemy; But the Committee of Estates, undaunted by

the check which the young Lord had given them, issued a Commission of Fire

and Sword to Argyll, authorizing him to capture both these strongholds.

The task was a congenial one to the ruthless Argyll; and with fiendish

glee he set about its accomplishment. Directing an overwhelming force

against the Castle of Airlie, he compelled Lord Ogilvy to withdraw, and

then, in pursuance of his instructions from the Committee, he proceeded to

raze the walls and battlements.

A contemporary writer

records that "Argyll was seen taking a hammer in his hand, knocking down

the hewed work of the doors and windows till he did sweat for heat at his

task." And the ancient ballad from which the following verses are quoted,

details, with perhaps some superfluous exaggerations, the poetical aspect

of the grim scene:—

"It fell on a day, and a

bonnie simmer day,

When green grew aits an’ barley,

That there fell oot a great dispute

‘Tween gleyed Argyll an’ Airlie.

Argyll has raised ane hunder men,

Ane hunder harnessed rarely;

An’ he’s awa’ by the back o’ Dunkeld

To plunder the Castle o’ Airlie.

Lady Ogilvy looks ower her bower

window,

An’ O, but she looks wearily;

An’ there she spied the great Argyll,

Come to plunder the bonnie house o Airlie.

‘Come down, come down, my Lady

Ogilvy,

Come down an’ kiss me fairly.’

'O, I wadna kiss the fause Argyll

Tho’ he shouldna leave a standin’ stane in Airlie.’

. . . . . .

‘O, I ha’e seven braw sons,’ she

said—

‘The youngest ne’er saw his daddie;

But tho’ I had ane hunder mae

I’d gi’e them a’ to King Charlie.

‘But gin my gude Lord had been

at

hame,

As this nicht he is wi’ Charlie,

There durstna a Campbell in a’ Argyll

Ha’e plundered the bonnie house o’ Airlie.

‘Gif my gude Lord was noo at hame,

As he is wi’ King Charlie,

The dearest blude o’ a’ thy kin

Wad slocken the burnin’ o' Airlie!

Thus runs the old song, and

though there seems too strong a flavour of the Trojan dame in this

Scottish matron, the strain proved prophetic, for her Lord had the

privilege on the bloody field of Kilsyth of executing summary vengeance

upon the Campbell clan in open battle.

Meanwhile, a partial

revenge had been taken upon the unfortunate Castle Campbell by the

followers of Montrose. After the "glorious victory" at Aulderne, that

intrepid leader descended by the east coast to the Forth, and then,

striking across the country by way of Kinross and Devon Valley, he thought

to surprise and capture Stirling with little effort. In his progress

westward he had to pass this stronghold of Argyll; and as the ruthless

conduct of the cross-eyed Earl at Airlie had been detailed to Montrose, he

relaxed discipline to allow the Ogilvies, who were with him, to indulge

their revengeful spirit. These were joined by the followers of the Earl of

Stirling, whose house of Menstrie, at the base of the Ochils, had been

relentlessly destroyed by the same hand. And as these avengers of blood

marched boldly up the narrow path towards the ancient Castle of Gloom,

well might the Campbells within its walls tremble

"To see the gallant Grahams come hame.

I’ll crown them east, I’ll crown them

wast,

The bravest lads that e’er I saw;

They bore the gree in free fechtin’,

An’ ne’er were slack their swords to draw.

They won the day wi’ Wallace wight.

They were the lords o’ the south countrie;

Cheer up your hearts, brave cavaliers,

The gallant Grahams ha’e come ower the sea!"

The resistance offered to

the assault must have been slight, since the position of the Castle might

have rendered defence easy. But the name of Montrose acted as a magic

spell upon his enemies; and this token of western power fell into the

hands of the warriors of the east, and was laid waste by fire and sword.

Nor have its lofty battlements since borne the Banner of Argyll, with the

Galley of Lorne, and the proud motto of the Campbells,

Ne obliviscaris.

Castle Campbell at night and thanks to Ken

Cameron for sending this in. |