|

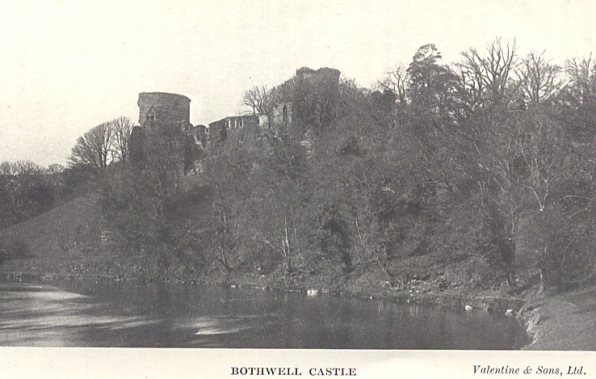

The ancient Castle of

Bothwell occupies a position more picturesque in its surroundings than the

majority of strongholds of early times. In the days when men had to fight

for the defence of their possessions it was usual for the lord of the land

to select a point difficult of access—some lonely peak, some sea-beaten

rock, or loch-encircled isle—as the spot most suitable for the erection of

his fastness, so that it might afford him a secure retreat from his foes

should Fortune turn against him. Hence, the most powerful in appearance of

the Castles of Scotland are those which frown from the bleak summits of

the barren hills of the north, or face the rude blasts which assail the

storm-lashed coasts of Ayrshire or East Lothian; which overlook from their

precipitous cliffs the profound depths of Loch Ness, like Castle Urquhart,

or rest on some tiny islet in the midst of a billowy lake—

"A

priceless gem, set in a silver sea."

like Lochleven Castle. But

Bothwell Castle presents none of these characteristics. The scenery which

surrounds it is essentially woodland and pastoral, and the quiet which

reigns in the vicinity seems somewhat out of keeping with the massive

towers and buttresses, which speak of inharmonious war in the midst of

peaceful repose.

The Clyde, flowing around

the domain of Bothwell, forms here a winding link, and wanders placidly

betwixt verdant banks crowned with varied foliage. From one point of view

the source and exit of the water are alike invisible, and the overhanging

boughs of the trees on either side of the river, as they seem to meet,

delude the spectator into the notion that he sees before him a still,

inland loch forming a natural moat for the Castle rather than a mighty

river pouring its resistless flood onwards to the ocean. From, the margin

of the river the banks rise in gentle slopes on either side, showing

patches of greenest verdure through the over-arching leaves of beech, of

birch, and of elm which fringe the water-edge and crown the grassy summits

of the confronting eminences. On the left bank of the river the ruins of

Blantyre Priory may be seen rising from the grey rock on which it was

founded about the beginning of the fourteenth century; while the grassy

mound on the right bank is surmounted by the remains of Bothwell Castle,

whose ivy-mantled walls have looked forth upon many changing epochs of

Scottish history, and whose halls have been trodden by both the friends

and foes of Scotland.

The ruins of Bothwell

Castle have been regarded by antiquaries as affording one of the finest

examples of its style of architecture in the kingdom. The date of its

erection is not accurately known, although it was certainly in existence

early in the thirteenth century. The plan of the Castle, as well as the

method of masonry employed, distinctly show that it was not the work of

native artizans; for in those times Scottish architecture was of the

rudest description. Possibly some enterprising Southern knight had

penetrated into the remote recesses of Clydesdale, and, enamoured of the

locality, had annexed it to his property, and built the Norman Castle

thereon. The size of the building itself would forbid the idea of its

having originated with any of the Scottish nobles of that distant time;

for there were few indeed among them wealthy enough to have undertaken

this task, even had they been civilized enough to conceive it. But as no

authentic record exists of the original builders, all is but conjecture.

The social position of its

first occupant may be imagined from the idea of its magnificence which the

ruins still convey. It has been constructed as an oblong quadrangle, with

inner court enclosed by vaulted buildings, probably with circular towers

at the corners, of which the greater part of two remain, although but

slight traces of the others now appear. An examination of the existing

ruins will show that the Castle covered an area of about 240 feet in

length, by 100 feet in breadth. The lateral extensions between the towers

are pierced irregularly with windows, but there are not sufficient

examples left to enable us to decide as to the nature and extent of the

chambers these walls contained. That it was devised as a stronghold is

evidenced by the strength of the outer wall, which is about 15 feet in

thickness, and stands nearly 60 feet high. Despite the almost defenceless

position which it occupies topographically, it is evident that no light

force would be necessary to win the Castle from resolute defenders.

Yet there are few Castles

on Scottish ground which have more frequently changed masters, and though

we cannot tell whose brain devised or whose hands upreared its towers, the

stories which are known of its chequered career link its history with that

of Scotland; and the Barons of Bothwell in chivalrous times for a long

period exercised vast power both in the Council and the camp of the

nation. Most of the structures of a similar kind, even if they have not

their beginning recorded, have at least accurate details of their

destruction; but the date of the erection of Bothwell Castle is unknown,

and the name of its destroyer can only be conjectured.

The first name associated

with a Castle of some kind at Bothwell is that of Olyfard, and the

connection of the family with Scotland may be traced. The family were of

long Norman descent, and the name appears in "Scalacronica" amongst the

Norman knights who fought on the side of William I. at the battle of

Hastings in 1066, and received grants of land in Northamptonshire from the

Conqueror. In 1113, when David I. of Scotland, sixth son of Malcolm

Caeamor, when Prince, became Earl of Northampton by marriage he came much

in contact with the Olyfards, and was godfather to the heir, David Olyfard.

This fortunate youth, though on the English side, was able to assist

David’s escape after the Battle of Winchester in 1141, and he accompanied

the fugitive King to Scotland, and became a prominent member of the

Scottish Court, and received many grants of lands from his godfather, the

King, becoming a generous benefactor to the Church. Though Bothwell is not

specially mentioned, it is evident that he had a seat there, as he gave a

contribution from Bothwell towards Blantyre Priory, the ruins of which are

close beside the ruined Castle. David Olyfard was made Justiciary of

Laudonio, which included the lands south of the Forth and on to the Tweed.

He was one of the first to establish feudalism in Scotland.

Walter Olyfard, the third

Justiciary by heredity, died in 1242, and though there is no known clue as

to the style and extent of Bothwell Castle in his time, it must have been

a place of importance as the regular seat of the Justiciary of the South

of Scotland. The statement has been made, and not disputed, that the

daughter of Walter Olyfard was married to Walter de Moravia, who was

ancestor of the Randolphs, Earls of Moray, and thus a new race came into

possession of Bothwell Castle and the surrounding district.

In the time of Alexander

II. the influence of England in the government of the northern part of the

kingdom had been experienced, and the unfortunate imprisonment of William

the Lion, the King’s father, had suffered the English to have some claim

to feudal superiority. The boldness of Alexander had prompted him to

oppose their efforts, and to seek to undermine the power of the throne of

England by joining with the Barons against King John. That monarch,

enraged at this presumption upon the part of his vassal, gathered together

an army of freebooters and desperadoes, invaded Scotland, crossing the

Humber, and laying waste the provinces between that river and the Forth.

The Scottish King was unable to oppose his march, and presently retired

until an accession of forces should join him. Then, ordering the Castles

of the knights who had joined him to be left in a defensive position, he

pursued King John by way of Berwick and chased him ignominiously to his

own country. At this time Bothwell Castle was in the possession of Walter

Olyfard, and would doubtless be considered a post of importance, as it lay

in the midst of a fruitful country, and was sufficiently apart from the

highway of England to escape the destruction with which the invading

armies usually overwhelmed their adversaries’ dwellings.

It was not to be expected

that a position of such strength as Bothwell must have been would long

escape the notice of the English. The armies which overran this portion of

the kingdom ere long discovered that the district of Clydesdale could

remain unsubdued whilst Bothwell and Dumbarton were in the hands of the

natives. Against the former of these, therefore, they directed their

endeavours, and with too fatal success. The delusive hopes which the

Scottish statesmen had built upon the apparent amity that existed for some

years betwixt Henry III. of England and his son-in-law, Alexander III.,

had been rudely shattered by the attitude which the former assumed upon

the question of the independence of Scotland. But Henry was too polite to

risk an open rupture with Alexander, and proceeded therefore by underhand

means to secure the division of the kingdom though fomenting discord while

professing friendship. His schemes were interrupted by the hand of Death;

but he bequeathed his policy to an able successor in the person of his son

and successor, Edward I.

How faithfully that monarch

fulfilled the desires of his much-lamented father need not here be told

except incidentally. Every one knows that Edward endeavoured to entrap his

brother-in-law, Alexander III., into rendering homage for the kingdom of

Scotland; that he took advantage of every pretext for interfering in

Scottish affairs during his life; that he expired in the very act of

leading an overwhelming army against the defenders of her liberty; and

that he directed that his tombstone should bear as its proudest motto the

self-assumed title of "Malleus Scottorum"—"The Hammer of the Scots." It is

not, therefore, necessary to dwell on all the details of this King’s

venturous career. When he visited Bothwell Castle in 1301 it was a very

different place from that which the Olyfards had left about fifty years

before. Sir Walter de Moravia had vast means at his command, and had

determined to erect a Castle worthy of the superb position. His wife, the

last of the Olyfards in Lanarkshire—the family were afterwards located at

Newtyle, Kinpurnie, and Gask in Perthshire—was at the Scottish Court, and

had met the second wife of Alexander II., the famous Marie de Coucy of

Picardy, who was married to the King in May, 1239, at Roxburgh. Now, in

1230, the Queen’s father, Enguerand III., Baron de Coucy, had just

completed the splendid Chateau de Coucy, in Picardy, which evidently has

been the model for the Bothwell Castle, possibly planned by Walter Olyfard,

but certainly completed by Walter de Moravia, no doubt with the prompting

of his wife, who may have sought to rival the Queen.

It has been shrewdly

suggested that Queen Marie may have brought to Scotland some of the Mason

Lodges that had been engaged on the Chateau de Coucy, and that these may

have been employed on the building of Blantyre Priory and Bothwell Castle.

The theory is by no means incredible, and accounts for the similarity of

the plans of Chateau and Castle. In any case it seems to be fairly

confirmed that Bothwell Castle was finished in a splendid fashion in 1278

or thereby.

The second Walter de

Moravia was married to a sister of John Comyn, one of the competitors for

the Scottish Crown; and he had two sons, William, who swore fealty to

Edward I. in 1291, and Andrew, the famous patriot, who supported Wallace,

and fell in September 1297 at the Battle of Stirling. His son, Thomas

Randolph, whose mother, Isabella, was a sister of King Robert the Bruce,

was also such a conspicuous hero in the War of Independence that Robert I.

conferred upon him the Earldom of Moray, and after the King’s death he was

Guardian of Scotland. Bothwell Castle was still the seat of the Earl,

though in 1299 it had been captured by the English. The place was visited

in 1301 by Edward I., who resided there for three days, and then placed

Bothwell in the charge of the English warrior, Aymer de Valence, Earl of

Pembroke, who was appointed Governor; and there is a consistent tradition

that the plan for the capture of Wallace was devised at Bothwell.

The career of De Valence

was varied, for though Edward I. trusted him with a large command,. he

fell under the suspicions of Edward II., who deprived him of many of his

honours. Bothwell was regarded as a safe retreat for fugitives from

Scotland, especially after Bannockburn. The Earl of Hereford, who had

commanded a wing of the English army at that conflict, sought to save his

soldiers by falling back on the Castle for shelter. Barbour relates the

incident thus :—

"The Erle of Herford frae

the melle

Departed with a great menyie,

And straucht to Bothwell took the way,

That in the Inglis mennis fay

Was holden as a place of wer."

Their attempt to withstand

the victorious Scottish army, however, was hopeless, and they were forced

to abandon the Castle. At a later date the first Earl of Moray had the

strange task allotted to him to dismantle his own Bothwell Castle and also

the Castles of Leuchars and St Andrews, to prevent them from being again

occupied by the English. The demolition was afterwards repaired by the

next noble family that came into possession of Bothwell Castle, though

traces may still be found of this incident.

Similarity of patriotic

feelings as well as pursuits had long held the families of Bothwell and

Douglas together. They claimed a common origin from some of the Flemish

families which had settled in Scotland at an early period, and their

determined resistance to the encroachments of England had saved the

country from conquest on several occasions. When, therefore, the race of

the first Randolph, Earl of Moray, terminated by the death of John, his

grandson, third Earl, who was killed at the Battle of Durham in 1346,

leaving no male issue, his brother, Thomas, who does not seem to have

assumed the title, died, leaving a daughter, it was not unnatural that a

union of these two families should be brought about by marriage. And thus

it happened that by the wedding of Archibald "the Grim," Earl of Douglas

(though an illegitimate son), with the heiress of Bothwell in 1381, the

Castle came into the possession of this powerful family.

Marjorie, the daughter of

this marriage, was united in wedlock to the unfortunate Duke of Rothesay,

son of Robert III., at the Parish Kirk of Bothwell in 1398, and though no

record exists to warrant the conclusion, there is every probability that

the marriage festivities took place at the Castle. For nearly a hundred

years the Douglas Earls held the Castle, and the strange manner in which

they came to lose it is worthy of notice.

Without accepting wholly

the fanciful tales which Hume of Godscroft relates as to the origin of the

Douglas family, it must be admitted that they can claim a very respectable

antiquity. Their historian maintains that they were almost the only family

of note that could trace back their ancestry to a purely Scottish source,

but his theory will hardly bear critical investigation; and the notion

that their progenitor was a man of mark "in the days of Solvathius, about

the year 767," will scarcely receive credence in these days. Hector

Boetius—not the most credible of historians—relates that Malcolm Ceanmor

held a Parliament at Forfar in 1061, at which he restored the estates that

had been reft from the Thanes by Macbeth, and empowered them to adopt

surnames from the localities where their lands lay. Amongst them was a

certain "Gulielmus à Douglas," who was

created first Lord of Douglas, and from him are derived the many and

honourable men who have borne a similar title. Their influence throughout

the struggles for Scottish Independence is very visible, and their growing

power upon the Border ultimately induced a rivalry with the reigning

family.

Latterly the Douglases held

the position of make-weight in all contests between England and Scotland;

for the series of Forts and Castles which they held throughout Lanarkshire

and Dumfriesshire could oppose a formidable barrier to either party, as

the Lord of Douglas willed. Perhaps the most romantic portion of their

history is that which relates to the "Good Sir James," the trusty

fellow-warrior of Bruce, and the chosen custodian of that monarch’s heart

when on its post-mortem journey to the Holy Land. Of him the old

rhyme still declares

"Good Sir James Douglas,

Who wise, and wight, and worthy was,

Was never over-glad for winning,

Nor yet over-sad for timing,

Good fortune and evil chance

He weighed both in one balance."

But the story of the early

adventures of the Douglas family belongs rather to the traditions

of

Douglas Castle than to Bothwell Castle, which

is our

present theme.

The fortunes of the

Douglases culminated in the person of Archibald, fourteenth Lord and fifth

Earl, and with him they began to waver and decline. Through his active

service in France he had won glory and wealth, and added several titles to

those which he had inherited. His full style was—Earl of Douglas, Earl of

Wigton, Lord of Bothwell, Galloway and Annandale, Duke of Touraine (in

France), Lord of Longueville, and Marshal of France. But when James I.

returned from his long imprisonment in England to assume the Crown of

Scotland, he found some of the more prominent nobles too powerful to be

tolerated, and suddenly cast many of them into prison, and the Earl of

Douglas among them. So far as can be judged, the chief offence of that

nobleman, besides his power, was a certain freedom of speech which he used

in advising the King, which that monarch could not endure. Disappointed by

this treatment, the Earl retired to France, and did not return till after

the assassination of the King.

He found Scotland in a most

pitiable condition. The policy of James I. had taught him to elevate men

of parts and understanding to places of trust in the kingdom despite their

inferior birth; and for the slight thus passed on their nobility the upper

grades of the Scottish nobles did not readily forgive him. When,

therefore, the Earl of Douglas found that the government of his native

land had been committed to Crichton and Livingstone of Callander—men of

good family, but of low degree in the peerage—whilst he had been excluded

from all share in the Councils of Scotland, he was not unnaturally moved

with resentment. It was shrewdly suspected by the nobles that these men

had been elevated to this high position as much for the purpose of

curtailing the power of the nobility as for any special faculties they

possessed; and the appointment of the Earl of Douglas to the post of

Lieutenant-General of the Kingdom was too evidently an extorted concession

to pacify them. The Earl by this time was too far advanced in years to

meddle with paltry matters of dispute. He retired in 1438 to Restalrig,

and died in that year.

William, sixth Earl of

Douglas, was only fourteen years old when he succeeded his father. He had

inherited all the late Earl’s courage and daring, and as the oppressions

of the Douglas family by the Stewart Kings was a frequent topic in

Bothwell Castle, the young Earl was somewhat unguarded in his speech about

them. Livingstone and Crichton became alarmed, and determined to have him

removed. Crichton wrote to him a hypocritical letter regretting the

discord betwixt the Earl and his kinsman, the King, and inviting him to

meet James II. at Edinburgh Castle, and aid him with advice. The young

Earl fell readily into the trap, and set out with his retainers for

Edinburgh. Crichton met him on the way, and lured him to his Castle of

Crichton, which he had just erected. For two days was the feasting and

revelry maintained there, and then the followers of Douglas, with David,

his younger brother, and his friend, Malcolm Fleming of Biggar, joined

Crichton’s band, and all set forth for Edinburgh. Arrived at the Castle,

Douglas was introduced to the King by Livingstone, and James felt, or

affected, strong attachment to the two brothers, sole heirs of an ancient

line. Several days were spent in entertaining them, and every mark of

attention was bestowed upon them.

At length the time arrived

for the consummation of the plot. One day, while at dinner in the presence

of the King, Crichton and Livingstone, with many of their followers,

suddenly rose upon the Douglases, and, as their attendants had been

carefully disposed of beforehand, they seized the unfortunate noblemen,

carried them out to the western courtyard of the Castle, and beheaded

them, without even the pretence of a trial. To give an air of legality to

the foul deed, Fleming was kept for four days, then beheaded on a plea of

treason. The traditional rhyme made upon the occasion is thus preserved :—

"Edinburgh Castle, Town and

Tower,

God grant thou sink for sin,

And

that even for the black dinner

Earl Douglas gat therein."

By this double murder the

direct line of the Douglases was terminated, and the title went to the

grand-uncle, mentioned by the historian of the family as "James the

Gross." His tenure of the title only lasted three years, when he was

succeeded by his eldest son, William, whose character more resembled that

of his uncle and cousin than of his weak and imbecile father. The plot of

Crichton and Livingstone had been devised astutely so as to terminate the

male direct line of successors, on the notion that the possessions of the

Douglases would probably be distributed amongst heiresses, and thus wipe

out the family. But their scheming was overturned to some extent by Earl

William, who reunited the dissevered portions of the vast estates of his

family by his marriage with Beatrix of Galloway, his first cousin, and

chief heiress of the alienated lands of Douglas. By this union the Earl

found himself in the position of the first subject of the realm. The

intention of the Stewart Kings had been to centralize all power in their

hands, and hitherto they had not scrupled to reduce the independence of

the greater nobles by flagrant acts of injustice. Fate had selected James

II. to be the chief instrument for the overthrow of the ancient house of

Douglas. The story of the King’s consenting to the murder of the two young

Douglases in November, 1448, has just been narrated; but the more

disgraceful murder by the King’s own hand in February, 1451—2, when

William, eighth Earl of Douglas, "was stabbed by King James II., and was

despatched by some of his courtiers in Stirling Castle." The story is told

in the account of "Stirling Castle" in this volume.

With James, ninth Earl of

Douglas, brother of the murdered Earl, the proud name of Douglas of

Douglas was brought nearly to extinction. Earl James, wishing to avenge

the murder of his brother, called out his retainers and also his three

younger brothers, and made a demonstration against the King; but some of

his allies deserted him, and when the King’s forces came out under George

Douglas, Earl of Angus, in May 1455, James, the ninth Earl, was defeated

at Arkinholme, and two of his brothers slain, and one made prisoner. In

June of this year Parliament passed sentence of forfeiture on James, ninth

Earl, and other members of the family.

For a long period after

1455 Earl James remained in England, and took no action against the

Scottish King. In 1483 he joined with Alexander, Duke of Albany, brother

of the new King, James III., in an expedition aimed at the deposition of

the King. But the times were sadly altered when Douglas found that

Annandale, Nithsdale and Clydesdale alike refused to rise at his bidding.

The Englishmen whom he had brought to invade the land of his birth were no

match for the hardy Border warriors, and fled at their approach. The Earl,

weary of the exile which he had been enduring, and ashamed of the disgrace

which had fallen upon him, yielded himself prisoner to one of his old

servants that a friend might have the advantage of the price put upon his

head. With a refinement of cruelty James III. condemned him to be confined

in the Abbey of Lindores during the remainder of his existence. He felt

most acutely that his life had been wasted when he heard the dread words

pronounced :—

"Go thou and join the living dead!

The Living Dead whose

sober brow

Oft shrouds such thoughts as thou hast now,

Whose hearts within are seldom

cured

Of passions by their vows abjured;

Where under sad and solemn show

Vain hopes are nursed, wild wishes glow.

Seek the Convent’s vaulted room,

Prayer and vigil be thy doom;

Doff the green and don the grey,

To the Cloister hence away!"

Perhaps not the least

bitter of his reflections in his enforced solitude would be that his

defeat had been brought about through the treachery of his kinsman, the

Earl of Angus, who had joined with the King against him. The members of

the Angus branch were notable for the fairness of their complexions,

whilst the Clydesdale Douglases were swarthy and dark in colour. Hence the

saying came into use after the fall of Earl James that "the Red Douglas

had put down the Black." The family historian endeavours to turn a

graceful compliment out of this fact, with which the account of the

Douglases in Bothwell Castle may be terminated:-

"Pompey by Caesar only was

o’ercome;

None but a Roman soldier conquered

Rome;

A Douglas could not have been

brought so low

Had not a Douglas wrought his

overthrow."

The estates that had

belonged to the Earl of Douglas, and were forfeited in 1455, at the time

of his departure for England, fell to the Crown, and King James had taken

the opportunity of partitioning these so as to secure some doubtful

adherents. Crichton, the son of the Chancellor who had compassed the

murders of the two Earls, received Bothwell Castle as the tardy reward of

his father’s treachery; and Sir James Hamilton of Cadzow, who abandoned

the cause of Douglas at this time, exchanged the lands of Kingswell for

those of Bothwell Forest, whilst the lands of Galloway were annexed to the

Crown. |