|

Plants in flower.—The water

shed.—Entering British Columbia.—Source of the Fraser River. —Yellow Head

Lake.—Serrated Peaks-—Benighted-—Moose Lake.—Milton and Cheadle.—Relics of

the Headless Indian.—Columbia River.—The three Mountain Ranges.—Horses

worn out.—First canyon of the Fraser.—The Grand Forks.—Changing locomotion

power—Robson's Peak.—Fine timber.—Tete Jauno cache-—Glaciers. Countless

Mountain Peaks.—A good trail.—Fording Canoe River.—Snow fence.— Camp

River.—Albreda.—Mount Milton.—Rank vegetation.—Rain.—A box in V's cache

for S. F—The Red Pyramid—John Glen.—The Forest.—Camp Cheadle.

September 16.—Our aim

to-day was to reach Moose Lake where Mohun's party was surveying. The

distances given us were; six miles to the summit of the Pass, six thence

to Yellow Head Lake, four along the Lake, and fourteen to Moose Lake.

These we found to be correct except the last which is more like sixteen

than fourteen, and unfortunately Mohun's party was near the west end of

Moose Lake, and this added eight more, so that instead of thirty, we had

to do forty. Besides, not having been informed that the second half of the

trail was by far the worst, no extra time was allowed for it, and hence we

had five hours of night travelling that knocked up horses and men, as much

as or more than a double day's ordinary work would have done In fact, the

day began well and ought to have ended well, but instead of that, it will

always be associated in our minds with the drive to Oak Point from the

North-west Angle on July 30th. Worse cannot be said of it.

The first half of the day

was more like a pleasure trip than work. The six miles to the summit were

almost a continuous level, the trail following the now smooth-flowing

Myette till the main branch turned north, and then a small branch till it

too was left among the hills, and a few minutes after the sound of a

rivulet running in the opposite direction over a red pebbly bottom was

heard.

We had left the Myette

flowing to the Arctic Ocean, and now came upon this, the source of the

Fraser hurrying to the Pacific. At the summit, Moberly welcomed us into

British Columbia, for we were at length out of "No man's land," and had

entered the western province of our Dominion. Round the rivulet running

west, the party gathered, and drank from its waters to the Queen and the

Dominion. No incline could be more gentle than the trail from the Atlantic

and Arctic to the Pacific slope. The road wound round wooded banks, a

meadow with heavy marsh grass extending to the opposite hill. There had

been little or no frost near the summit, and flowers were in bloom that we

had seen a month ago farther east. The flora was of the same character on

both sides of the summit; eight or nine kinds of wild berries, vetches,

asters, wild honey-suckle, &c, &c. Good timber, the bark of which looked

like hemlock, but that the men called pine, covered the ground for the

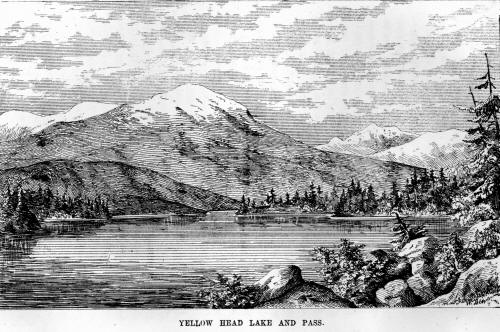

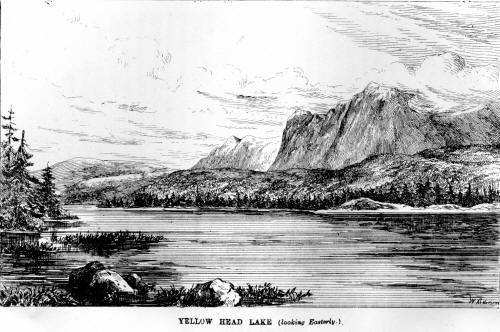

next few miles to Yellow Head Lake. This beautiful sheet of water, clear

and sparkling up to its firm pebbly beach, expanding and contracting as

its shores recede or send out promontories, was absurdly called "Cowdung

Lake" formerly, but ought always to bear the same name as the Pass.

Towards the western end where we halted for dinner, its woods have been

somewhat marred by fires that have swept the hill sides, but wherever

these have kept off, its beauty is equal to, though of a different kind

from Lake Jasper. Low wooded hills intersected with soft green and flowery

glades rise in broken undulations from its shores. It is on those and up

to the line of vegetation that a botanist should go; for there are few

varieties along the low ground, but evidently many higher up. Above and

behind the hills on the south side, towers a huge pinnacle of rock, the

snow on whose summit is generally concealed by clouds or mist. On the

north, the two mountains that we had seen yesterday, bounding the Pass on

that side, and which had been hidden all the forenoon by the woods at

their base, through which the trail runs, now looked out from right over

our heads; riven masses of stratified rock, in a slightly curved line,

forming a gigantic cross-cut saw. Through the Pass slate cropped out in

several places, and boulders of granite strewed the ground, but the

granite was not observed in situ. Probably, slate is what gold miners term

"the bed rock," and Brown and Beaupré pointed out quartz veins that they

had no doubt were gold bearing.

After dinner the trail, from the nature of the

soil, was so rough that the horses could go only at a walk of three miles

an hour It ran either among masses of boulders, or through new woods,

where the trees and willows had been cut away, but their sharp stumps

remained. It was dark before we reached the east end of Moose Lake, and if

all our party had been together, we would certainly have camped beside one

of the many tributaries of the Fraser, that run down from every mountain

on both sides, after it emerges from Yellow Head Lake, and make it a deep

strong river before it is fifteen miles long. One of those mountain

feeders that we crossed was an hundred feet wide, and so deep and rapid in

two places, that the horses waded across with difficulty, and had almost

to swim. Our company, however, was unfortunately separated into three

parts, and no concerted action could be taken. Moberly and the Doctor had

ridden ahead to find Mohun's Camp and have supper ready; the pack-horses

followed three or four miles behind them; and the Chief, Frank, and the

Secretary were far in the rear, botanising and sketching. Every hour we

expected to get to the Camp, but the road seemed endless. In the dense

dark woods, the moon's light was very feeble, and as the horses were done

out, we walked before or behind the poor brutes, stumbling over loose

boulders, tripped up by the short sharp stumps and rootlets, mired in deep

moss springs, wearied with climbing the steep ascents of the lake's sides,

knee-sore with jolts in descending, dizzy and stupid from sheer fatigue

and want of sleep. A drizzling rain had fallen in showers most of the

afternoon, and it continued at intervals through the night; but our

exertions heated us so much that our clothes became as wet, on account of

the waterproofs not allowing perspiration to evaporate, as if we had been

thrown into the lake; and thinking it less injurious to get wet from

without than from within, we took off the waterproofs, and let the whole

discomfort of the rain be added to the other discomforts of the night. The

only consolation was that the full moon shone out occasionally from rifts

in the clouds, and enabled us to pick a few steps and avoid some

difficulties. At those times the lake appeared at our feet, glimmering

through the dark firs, and shut in two or three miles beyond by

precipitous mountains, down whose sides white torrents were foaming, the

noise of one or another of which sounded incessantly in our ears till the

sound became hateful.

This kind of thing lasted in the case of the

three in the rear fully five hours. The men with the pack-horses had got

in to camp half an hour, and Moberly and the Doctor two hours before them.

None of us were in good humour, because we felt there had been stupid

bungling or carelessness on the part of those who should have guided us,

as no one would have dreamed of attempting such a journey if proper

information had been given. And to crown this disastrous day, there was no

feed about Mohun's camp, and his horses that we had expected to change

with ours, had left a few days previously for Tete Jaune Cache. His men

had a raft made on which to transport their luggage and instruments up to

the east end of the lake, as their first work for to-morrow. They had

completed the survey along the west end and centre. Our poor horses, most

of which had now travelled eleven hundred miles, and required rest or a

different kind of work, had had a killing day of it and there was no grass

for them. Reflecting on the situation was not pleasant, but a good supper

of corned-beef and beans made us soon forget sleep. A drizzling rain had

fallen in showers most of the afternoon, and it continued at intervals

through the night; but our exertions heated us so much that our clothes

became as wet, on account of the waterproofs not allowing perspiration to

evaporate, as if we had been thrown into the lake; and thinking it less

injurious to get wet from without than from within, we took off the

waterproofs, and let the whole discomfort of the rain be added to the

other discomforts of the night. The only consolation was that the full

moon shone out occasionally from rifts in the clouds, and enabled us to

pick a few steps and avoid some difficulties. At those times the lake

appeared at our feet, glimmering through the dark firs, and shut in two or

three miles beyond by precipitous mountains, down whose sides white

torrents were foaming, the noise of one or another of which sounded

incessantly in our ears till the sound became hateful.

This kind of thing lasted in the case of the

three in the rear fully five hours. The men with the pack-horses had got

in to camp half an hour, and Moberly and the Doctor two hours before them.

None of us were in good humour, because we felt there had been stupid

bungling or carelessness on the part of those who should have guided us,

as no one would have dreamed of attempting such a journey if proper

information had been given. And to crown this disastrous day, there was no

feed about Mohun's camp, and his horses that we had expected to change

with ours, had left a few days previously for Tete Jaune Cache. His men

had a raft made on which to transport their luggage and instruments up to

the east end of the lake, as their first work for to-morrow. They had

completed the survey along the west end and centre. Our poor horses, most

of which had now travelled eleven hundred miles, and required rest or a

different kind of work, had had a killing day of it and there was no grass

for them. Reflecting on the situation was not pleasant, but a good supper

of corned-beef and beans made us soon forget our own fatigue. After

supper, at 2 P.M., wrapping dry blankets round our wet clothes, and

spreading waterproofs over the place where there were fewest pools of

water, we went in willingly for sweet sleep.

The Doctor had completely forgotten his

fatigue before our arrival under the influence of a present of the spoon

and fishing line of Milton and Cheadle's "Headless Indian." One of the

packers had found the skeleton, and had also found the head lying under a

fallen tree, a hundred and fifty yards from the body. As the body could

not have walked away and sat down minus the head, the explanation of the

packers was that the Assiniboine on his unsuccessful hunt for game had

killed and eaten the Shuswap, and turned the affair into a mystery by

hiding his head. Poor Mr. O'B., of whom we heard enough at Edmonton to

prove that his portraiture is faithfully given in "the North-west Passage

by land," will accept this solution of the mystery if no one else will.

The Doctor put the old horn spoon, and the fishing line—a strong native

hemp line, among his choicest treasures, and took minute notes of the

position of the grave that he might dig up the head.

The two descriptions in Milton and Cheadle

that have been generally considered apocryphal, and that have discredited

the whole book to many readers, are those concerning Mr. O'B., and 'the

headless Indian.' Not only did we find both verified, but the accounts of

the country and the tale of their own difficulties are as truthfully and

simply given as it was possible for men who travelled in a strange

country, chiefly in quest of adventures that they intended to publish, and

who naturally wished to get items with colour for their book. The pluck

that made them conceive, and the vastly greater pluck that enabled them to

pull through such an expedition was of the truest British kind. They were

more indebted than they perhaps knew as far as "Slaughter Camp," to the

trail of the Canadians who had preceded them, on their way to Cariboo; but

from that point, down the frighful and unexplored valley of the North

Thompson, the journey had to be faced on their own totally inadequate

resources. Had they but known it, they were beaten as completely as by the

rules of war the British troops were at Waterloo. They should have

submitted to "the inevitable" and starved. But luckily for themselves and

for their readers, they did not know it; and thanks to Mrs. Assiniboine,

and their own intelligent hardihood that kept them from giving in even for

an instant, they succeeded where by all the laws of probabilities they

ought to have disastrously failed.

We had now crossed the first range of the

Rocky Mountains, and were on the Pacific slope, on the banks of a river

that runs into the Pacific Ocean. One or two of our party seemed to think

that difficulties were therefore at an end ; that all that had to be done

now was to follow the Fraser to its mouth, as so great a river would be

sure to find the easiest course to the sea. A party of gentlemen ignorant

of the geography of the country and deserted by their guides, in

endeavouring to cross the Rocky Mountains a few years ago farther south,

argued similarly when they struck the Columbia river. 'So great a river

cannot go wrong: its course must be the best; let us follow it to the

sea.' And they did follow its northerly sweep round the Kootanie or

Selkirk range, for one or two hundred miles, till inextricably entangled

among fallen timber, and cedar swamps, they resolved to kill their horses,

make rafts or canoes, and trust to the river. Had they carried this plan

out, they would have perished, for no raft or canoe can get through the

terrible canyons of the Columbia. But fortunately two Shuswap Indians came

upon them at this juncture, and though not speaking a word that they knew,

made them understand by signs, that their only safety was in retracing

their steps, and by getting round the head waters of the Columbia, reach

Fort Colville by the Kootanie Pass.

Just as the Columbia has to sweep in a great

loop round the Selkirk range, so in exactly a similar way farther north or

northwest, has the Fraser to loop round the Gold range. Those two ranges

may be considered one, with a gap or long break in it between the northern

bend of the Columbia and the point called "Tete Jaune Cache" where the

Fraser has to turn to the north. It is evident then that the true course

for a traveller, from Yellow Head Pass to the west, since he cannot cross

the Gold Mountains, which stretch in line across his direct path, is to

turn south east a little, try for a road by this gap, and overcome the

Gold Mountains by flanking them.

The reader must understand, that although

there are many cross-sections and subdivisions of the Rocky Mountains

called by different names, there are three main ranges that have to be

traversed in going to the Pacific. In the United States and Mexico these

ranges bear different, but all well known names. As compared with the

mountains farther north, two points may be noted concerning them. First,

that they are not cloven by river passes. A Railway therefore has to climb

to the high plateau that is nearly as high as the summits. Secondly, that

they stretch, especially in the United States, over a far greater extent

of country from east to west than is the case in British America.

Our three ranges are the Rocky Mountains

proper ; the Selkirk and Gold, which may be considered one ; and the coast

range or Cascades. The passage from the east through the first range, is

up the valley of the Athabasca and the Myette, and we have seen how easy

it is, especially for a Railway. The average height of the mountains above

the sea, is nine thousand feet; but the Yellow Head Pass is only three

thousand seven hundred feet. On each side of the valley are mountains that

act as natural snow-sheds.

The next question is, are there similar

valleys and passes through the other two ranges? Yes, but not so direct

and broad, and there are many obstacles to be overcome. How to get through

the second range has always been considered the great difficulty.

First, we have to get to it from Yellow Head

Pass. This is done by following the Fraser, as we did to day to Moose

Lake, and as we shall to-morrow, to Tete Jaune Cache. There we expect to

see the Gold range stretching in unbroken line before us, forcing the

Fraser far to the north, and us somewhat to the south east and then the

south. Oh! for a direct cut through to the Cariboo gold fields like that

which the Athabasca cleaves the Rocky Mountains with! Search for such a

Pass has not been given up, and even though no Pass be found, there is

hope that a short tunnel may yet "cut the knot," and solve all

difficulties. But in the mean time our only course from Tete Jaune Cache,

will be to slip in between the Gold and Selkirk ranges till we strike the

North Thompson, and continue the flanking process, by going down its banks

southerly till we get to Kamloops at the junction of the North and South

Thomson, where we can recommence our westerly course, along the

comparatively low lying plateau, extending between the second range, and

the third called the Cascades.

September 17.—We are now in the heart of the

Rocky Mountains, between the first and second great ranges, nearly a day's

journey on from Yellow Head Pass, with jaded horses, and a trail so heavy

that fresh horses cannot be expected to average more than twenty miles of

travel per day. This

morning the consequences of last night's toil and trouble showed plainly

by a multitude of signs. Breakfasted at 9 A.M., started from Moose Lake

Camp at midday, and crawled ahead about four miles, the horses lifting

their feet so spiritlessly that at every step we feared they would give

out wholly. At an open glade here, the feed was pretty good, though

cropped closely by the dozen horned cattle, kept for the purpose of

furnishing fresh beef for Mohun's party, and it was decided that it would

be wise to camp. The

delay was not lost time, however vexatious the mismanagement that

necessitated it. The Chief had to receive reports about all that had been

done by the engineers in this quarter, inspect the line of survey and the

drawings that had been made; and give instructions not only for Moberly's

parties, but through him for others. Besides, all of us needed a long

night's rest, and a big fire to dry our clothes and blankets at before

going farther. For assurances were volunteered all round that we had a

full fortnight of no holiday travel before reaching Kamloops.

Mohun accompanied us until we should fall in

with the pack-train on its way up from the Cache, in order to arrange

about an exchange of our jaded and unshod horses for others fresh and

shod. Moose Lake that

we struck last night but only got a tolerable view of to day, is a

beautiful sheet of water, ten or eleven miles long, by three wide. It

receives the Fraser, already a deep strong river fully a hundred and fifty

feet wide, and also drains high mountains that enclose it on the north and

south. The survey for the Railway is proceeding along the north side,

where the bluffs though high appeared not so sheer as on the south. The

hillsides and the country beyond support a growth of splendid spruce,

black-pine, and Douglas fir, some of the spruce the finest any of us had

ever seen. So far in our descent from the Pass, the difficulties in the

way of railroad construction are not formidable. nor the grades likely to

be heavy. Still the work that the surveyors are engaged on requires a

patience, hardihood, and forethought that few who ride in Pullman cars on

the road in after years will ever appreciate.

September 18th.—Got away from camp at 8

o'clock. Soon after, struck the Fraser, rushing green and foaming through

a. narrow valley, closed in by high steep rocks wooded beneath and bare

from half-way up. As we advanced, a change in the vegetation, marking the

Pacific slope, began to show distinctly. The lighter green of cypress

mingled with the darker woods tilt it predominated,—white birch and small

maples also coming in. Our jaded horses walked quietly along, at the

two-and-a-half miles per hour step, on a trail heavy in the best places,

across mountain streams rushing down to join the Fraser the worst of them

roughly bridged with logs and spruce boughs ; around precipitous bluffs

and hills, and through mud-holes sprinkled heavily with boulders.

Frequently we came on the stakes of the surveying party who had used the

trail where there was but one possible course for any road. After

travelling nine miles Mohun invited us to tie our horses to the trees, and

go down two hundred yards to see the first canyon of the Fraser. A canyon

is simply a mountain gorge in which the river is obliged to contract

itself, by high rocks closing it in on both sides. A river, however, is

not needed to form a canyon; for walled rocks, enclosing a narrow

waterless valley constitute a canyon. At this first canyon, the rocks

closed in the river for some hundred yards to a width of eight feet, so

that a man could jump across. Down this narrow passage, the whole of the

water of the river rushed, —a resistless current, slipping in great green

masses from ledge to ledge, smashing against out-jutting rocks, eddying

round stony barriers till it got through the long gate-way. In some places

these canyons are merely rocks near the stream; in others they are bluffs

extending far back, or perhaps one great bluff that had formerly stretched

across the river's bed, and had been riven asunder. In either case, they

present formidable obstacles to railroad construction.

A mile beyond, we came to the "Grand Fork of

the Fraser," where the main stream receives from the north-east, a

tributary important enough to be considered one its sources. It flows in

three great divisions, through a meadow two miles wide, from round the

bases of Robson's Peak,—the monarch of the mountains hereabouts, and his

only less mighty satellites whose pyramidal forms cluster in his rear. A

mile from the first division, we came to the second, and found the first

section of Mohun's pack-train in the act of crossing it towards us. This

first section consisted of horses; and the second of mules led by a bell

horse, under the supervision of Leitch, the chief packer, followed a mile

behind. A general halt was called, and Leitch sent for. No difficulty was

found in making new arrangements. He gave us four fresh pack horses which

would now be sufficient for our wants, five saddle horses, and two

packers, and took all our horses, and Brown, Beaupré, and Valad to help

him—Valad being specially entrusted with the duty of taking back six

horses of the Hudson Bay that were among ours. This was an entire

reorganization, and again Terry was the only one of the old set that

remained with us. He wished to go on to Cariboo and make his fortune at

the mines there. A vision of gold nuggets, picked up as easily as diamonds

and rubies in Arizona, more than any sentimental attachment to us was at

the root of his stedfastness. But it grieved all to part from the other

three, and they seemed equally reluctant to turn their backs on us.

Beaupré's only consolation was that he would get pemmican again, for he

declared that life without pemmican was nothing but vanity; and we had

made the huge mistake of exchanging our pemmican with McCord for pork. The

next day and every day after we rued the bargain, but it was too late.

Beaupré and Valad had suffered grievously in body from the change, and for

an entire day had been almost useless. The Doctor was reduced practically

to two meals a day, for he could not stand fat pork three times. Indeed

all, with the single exception of Brown, lamented at every meal, as they

picked delicately at the coarse pork, the folly of forsaking that which

had been so true a stand by for three weeks. The Chief gave Brown and

Beaupré letters to Moberly, the latter having returned to the Jasper

valley two days ago. In now taking leave of these fine fellows, it is with

the hope that they may be entrusted with positions in which they will be

able to exercise their good qualities in the service of the country. Valad

made his adieus, and received the gratuity that the Chief gave him, with a

dignity that only an Indian or a gentleman of the old school could

manifest. And so exeunt, Brown, Beaupré and Valad.

It was only two P.M. when Leitch came up; but

his horses had been travelling all day, and as we were in a good place for

feed and for our own dinner, he advised that camp should be pitched, and

no movement onward made till the morrow, as time would really be gained by

the delay. This was agreed to, the more readily because the Chief had

further instructions to write and send back by Mohun, and because the

clouds that had been floating over the tops of the hills all day, and

obscuring the lofty glacier cone of Robson's Peak, began to close in and

empty themselves. Looking west down the valley of the Fraser, the narrow

pass suddenly filled with rolling billows of mist. On they came, curling

over the rocky summits, rolling down to the forests, enveloping everything

in their fleecy mantles. Out of them came great gusts of wind that nearly

blew away our fires and tents; and after the gusts, the rain in smart

showers. Once or twice the sun broke through, revealing the hill sides,

all their autumn tints fresh and glistening after the rain, and the line

of their summits near, and bold against the sky; all, except Robson's Peak

which showed its huge shoulders covered with masses of snow, but on whose

high head masses of clouds ever rested.

Brown made us a plum cake for tea, and in

honor of the occasion, a tin of currant jam that had been put up to be

eaten with mutton, if bighorn were shot, was produced. On being opened, it

turned out to be only tomatoes, to our great disappointment, but still it

was a variety from the routine fare, and relished accordingly.

Sept. 19th.—It rained during the night and the

morning looked grey and heavy with clouds ; but the sun shone before

eleven o'clock, and the day turned out the finest since crossing the

Yellow Head Pass. At 7.30 A.M. got off from the camp, giving a last cheer

to Brown, Beaupré, and Valad; and casting many a longing look behind to

see if Robson's Peak would show its bright head to us. But only the

snow-ribbed giant sides were visible, for the clouds still rested far down

from the summit. Three miles from camp, beside the river, at a place

called "Mountain view," his great companions stood out from around him;

but he remained hidden, and reluctantly we had to go on, without being as

fortunate as Milton and Cheadle.

Our new horses were in prime condition; but

the road for the first eleven miles was extremely difficult; and last

night's rain had made it worse. The trail follows down the Fraser to "Tete

Jaune Cache," when it leaves the river and turns south-east to go to the

North Thompson, at right angles to the main course we had followed since

entering the Caledonian Valley. The Fraser at the same point changes its

westerly for a northerly course, rushing like a race horse, for hundreds

of miles north, when it sweeps round and comes south to receive the united

Waters of the North and South Thompson, before cutting through the Cascade

Range and emptying into the ocean. Tete Jaune Cache is thus a great centre

point. From it the valley of the Fraser extends to the north, and the same

valley extends south by the banks of the Cranberry and of the Canoe Rivers

to the head of theColumbia,—a continuous valley being thus formed parallel

to the East range of the Rocky Mountains, and separating them from the

Gold and Selkirk ranges.

Our first "spell" to-day was eleven miles over

a road so heavy that it cost our fresh horses three and a half hours tough

work. It hugged the

banks of the river closely, passing through timber of the finest

kind—spruce, hemlock, cedar, (a different variety from the white or red

cedar in the eastern provinces) white birch and Douglas fir. Small maples,

Mountain ash, and other varieties also showed. An old Iroquois hunter,

known in his time as Tete Jaune or Yellow Head, probably from the

noticeable fact in an Indian of his hair being light coloured, had wisely

selected this central point for caching all the furs he got in the course

of a season on the Pacific slope, before setting out with them to trade at

Jasper House. He has given his soubriquet forever, not only to the Cache,

but to the Pass and the Lake at the summit. Two or three miles to the east

is a roaring linn of the Fraser with a fall of from fourteen to twenty

feet; but we did hot go off the road to see it. At the Cache, lofty,

glacier clothed mountains rose in all directions up and down the valley of

the Fraser, the Cranberry, and the Canoe—enough peaks to hand down to

posterity the names of all aspiring travellers and their friends for the

next century. The Gold Mountains formed in unbroken line right across our

path, forbidding any further progress west, and forcing us to go

south-east to flank them, as they forced the Fraser to the north. To our

great comfort there is stationed at the Cache a large boat of the C. P. R.

S. and into it were pitched saddles and packs, and we rowed ourselves

across while the horses swam. The Fraser, at this early stage of its

course, is as broad and strong as the Athabasca below the Jasper valley.

As the packs were off the horses, we halted for dinner, and at one o'clock

were on our way again, "hustling" at a great rate to make up for the slow

progress of the last two days. Jack and Joe, our new packers proved to be

no idlers. The one was a New Bruswicker who had spent years among the

Rocky Mountains, chiefly in the United States; the other an Ontarian,

settled in British Columbia,—both sharp, active fellows, knowing a good

deal of human and still more of horse nature.

Our second "spell" was

twenty miles, south-east and south to the crossing of the Canoe River. The

trail here was in excellent condition, and for great part of the way a

buggy might have been driven on it. A sandy ridge like a hog's-back runs

up the east side of the valley of the Cranberry, and the trail is along

it's top. This valley is the connecting link between the Fraser and Canoe

rivers. The valley of the Canoe is the larger link again, extending to

"Boat encampment" at the northern end of the valley of the Columbia. The

black pines on the ridge are so well apart that there is no difficulty in

diverging from the trail, and going in different directions. Before us, as

we journeyed south with a little easting, snowy peaks rose on each side of

the wide valley, dwarfing it, in appearance, to an extremely narrow width

; while right ahead a great mountain mass that marked the beginning of the

main valley of the Canoe, seemed to close our way. The trees struggled far

up the sides, fighting a battle with the bare rocks and the snows,—the

highest trees heavily dusted with last night's snowfall. Crossing a little

stream called the McLennan that issues from a pass in the side hills, we

rounded Cranberry Lake and saw the valley of the Canoe stretching far up

in the direction we had been going, while our road was across the river

and up the dividing line S.S. W. to Albreda Lake and River, flowing into

the Thompson.

Although only five o'clock, the sun was now setting behind the mountains

to the west from which the Canoe issues, and the road here was heavy with

recent rainfall, boulders, and mud-holes, so that there was no use of

pushing on much farther. At the "Crossing" of the Canoe, there was a raft

on the other side, but as the river had fallen two feet in the course of

the day, we tried the ford and found it quite practicable,—the water not

coming much higher than the horses' shoulders; so that the "Crossing"

which had so nearly cost Lord Milton and Mrs. Assiniboine their lives did

not delay us ten minutes.

The rapidity with which these mountain

torrents increase or decrease in depth is an astonishing feature to those

who have been accustomed only to Lowland rivers. A warm day melts the

snows high up, and there is an increase in depth by the afternoon, of from

six inches to two or three feet. A cold night succeeds, and down the

stream falls by morning. That the Canoe had fallen during the day, was

proof that though warm in the valley, the air was cold in the mountains.

This is pretty much the state of matters as regards weather all through

the winters here. The high mountains not only protect the valleys from

much of the cold, but also from much of the snow. They act as natural snow

fences. As the sun had now disappeared, though his light still shone on

the double range of high peaks stretching away down the Canoe, camp was

pitched on the other side of the river, Jack and Joe proving themselves as

expeditious and obliging as even Brown and Beaupré. It was amusing to

listen to the slang terms of the Pacific that garnished their talk.

"Spell" we found had crossed the mountains, and "spelling place" and a

"good spell" were as common on the one side as the other. But Jack's call

to his horses was new to us. "Git" probably the abbreviated form of our

"get up," and Terry's "git up out o' that," was the only cry ever

addressed to them, and the sound of it would quicken their walk into a

trot when no other words in the language would have the slightest effect.

This transatlantic senten-tiousness and love of abbreviations, from which

come their "Sabre cuts of Saxon speech" characterized all their

conversation. Without intending the faintest disrespect, they addressed

the Doctor always as "Doc." "Good morning Doc," meant no more than "good

morning my Lord" would mean. Even the grandeur of the mountains did not

secure to them their name in full. "They call them 'the Rockies,'" said

Jack, jerking his head in their direction, with an air that indicated that

no further information was required about such things. Every adjective and

article that could, in any way, be dispensed with was rejected from their

English; and if syllables could be lopped off long words so as to bring

them down to one syllable, the axe was unsparingly applied. Thus, San

Fransisco was always "Frisco," and Captain —a name applied

indiscriminately to every stranger—never longer than "Cap."

September 20th.—Up early this morning and,

after breakfast on bread and pork—very unlike Irish pork—for not a

solitary streak of lean relieved the fat, got away at 6.30 A.M., before

the sun had looked out over the mountains. From our camp a singular

radiation of valleys could be observed. That of the Canoe ran almost north

and south, inclining more to the west up stream. Between the west and

south, the valley of one of its tributaries joined it. Along this

tributary called the Camp River—from the fact of one of the surveying

parties wintering on it last year—our course was to be to-day. Between the

east and north the valley of the Cranberry, along which we had travelled

yesterday afternoon, extended away to the Fraser.

Our aim to-day was to reach the North

Thompson. Between our camp and it, thirty-three miles of bad road had to

be travelled. Broad

gravel benches, supporting a growth of small black pines, rose one above

another like terraces, the highest attaining a height of four or five

hundred feet. Up these the trail led, heading across to Camp River.

Similar benches of sand or gravel, or of sand mixed with boulders are a

characteristic of all the rivers in British Columbia. They are distinctly

defined as the successive banks of the smallest as well as of the largest

rivers. Those along the Canoe, are so extensive as to show that a much

greater volume of water once flowed over or rested in the valley. It may

be that the Columbia, before the present canyons through which it now runs

to the south were riven, flowed thus far or farther north.

It seemed to us a great mistake that the old

Indian trail had not been abandoned here, and a new trail made. The

terraces are so steep and high, and the descent on the other side to the

valley of Camp River so sudden, that the only explanation we could suggest

of the trail facing up and down instead of rounding them, was that Tete

Jaune had first made it when chasing a chamois or bighorn, and that he and

all others thereafter, McCord's party included, were too conservative to

look for another and better way.

At the summit of the divide, Camp River flows

opposite ways from the two ends of a sluggish lake, the part that runs

down to the Thompson assuming the name of the Albreda. The valley is

narrow and closed in at its south-west end by the great mass of Mount

Milton which fronted us the whole day. This mountain that Dr. Cheadle

selected to bear the name of his fellow traveller is a mass of snow-clad

peaks that feed the little Albreda with scores of torrents, ice-cold and

green coloured, and make it into a river of considerable magnitude before

it flows into the Thompson. It is on the south of the Albreda and not on

the north as stated by them, and the trail winds round its right or north

side leaving it on the left. Soon after entering the valley of Camp River

we saw it before us, towering high above the hills that enclosed the

narrow valley, and seeming to bar our further progress to the south and

south-west. A semi-circle of five peaks, enclosing a snowy bosom, forms

the left side; and, next to these, four much higher rise, the highest and

largest in the centre showing a broad front of snow like a field, inclined

down till hidden by a forest of dark firs on a range of lower hills. Our

road which at first was up the narrow fire-desolated, stony valley, led

next round the base of these lower hills, and from the difference of soil

and of elevation, changed from a succession of bare, stony ridges, into a

succession of mud-holes and torrents— bridged, fortunately for us, by the

trail party—till we came to the first crossing of the Albreda. The timber

here was of the largest size, but many of the noblest looking cedars were

evidently not of much worth from internal decay. It was after sunset when

we passed over the wooded slopes and along the banks of the river, and as

the dark forest opened here and there, one white peak after another came

out through a broad rift in the wooded hills. The underbrush consisted

chiefly of a great variety of ferns of all sizes, from the tiniest to

clusters six feet high, or of the broad aralea which so monopolized all

light and moisture where it grew that there was no chance for grass. In

some marshes a water-lily, with leaves three feet long, in seed at this

season, hid the water as completely as the aralea the ground. Everything

on this side of the mountains is on a large scale,—the mountains

themselves, the timber, the leaves, ferns, etc.

It was still eight miles to the crossing of of

the Thompson. Since starting in the morning we had halted only once, and

yet had made barely twenty-five miles. But as the fast gathering darkness,

twice as deep too because of the forest, compelled it, our fifty-fifth

camp from Lake Superior was pitched beside the Albreda.

September 21st.—Up this morning at 4.30, in

the dark, and on the road two hours later. The days were now so short,

because of the season of the year and the mountain-limited horizon, that

as it was impossible to travel on the trail after nightfall, the most had

to be made of the sunlight.

The trail for the first eight miles was as bad

as well could be, although a great amount of honest work had been expended

on it. Before McCord had come through, it must have been simply impassable

except for an Indian on foot,—worse than when Milton and Cheadle forced

through with their one pack-horse at the rate of three miles a day; for

the large Canadian party had immediately preceded them, whereas no one

attempted to follow in their steps till McLellan in 1871, and in the

intervening nine years much of the trail had been buried out of sight, or

hope-lesly blocked up by masses of timber, torrents, landslides, or

debris. Our horses, however, proved equal to the work. Even when their

feet entangled in a network of fibrous roots or sunk eighteen inches in a

mixture of bog and clay, they would make gallant attemps at trotting; and

by slipping over rocks, jumping fallen trees, breasting precipitous

ascents with a rush, and recklessly dashing down the hills, the eight

miles to the crossing of the Thompson were made in three hours.

The early morning was dark and lowering, and

at eight o'clock a drizzle commenced which continued all the forenoon.

Struggling through sombre woods and heavy underbush, every spray of which

discharges its little accumulation of rain on the weary traveller as he

passes on, is disheartening and exhausting work. The influence of the rain

on men and horses is most depressing. The riders get as fatigued as the

horses; for jumping on and off at the bogs, precipices, and boulder slides

thirty or forty times a day is as tiresome as a circus performance must be

to the actors. We

crossed the Thompson at a point where it divides into three, the smallest

of the three sections being bridged with long logs, the two others, broad

and only "belly deep," as Jack phrased it. Riding down the west side, too

wet and tired to notice anything, the men in advance passed a blazed tree

with a piece of paper pinned to the blaze; but the Secretary, being on

foot, turned aside to look; and read,—

"In V's Cache

There is a box for S. Fleming

or M. Smith."

He at once called out the

good news, and V's Cache in the shape of a small log shanty was found hard

by. Jack unroofed it in a trice and jumped in; and among other things,

stored for different engineering parties, was the "box." A stone broke it

open, and as Jack handed out the contents, one by one, a general shout

announced their nature.—Candles and canned meats ; good. "Hooray," from

the rear! Two bottles of Worcester sauce and a bottle of brandy! better;

sauce both for the fat pork and for the plum-pudding next Sunday. Half a

dozen of Bass' Pale Ale, with the familiar face of the red pyramid brand!

Three times three and one cheer more! After this crowning mercy, more

canned meats, jams, and a few bottles of claret evoked but faint applause.

The wine and jams were put back again for Mr. Smith. Four bottles of the

ale, a can of the preserved beef, and another of peaches were opened on

the spot, and Terry producing bread from the kitchen sack, an impromptu

lunch was eaten round the Cache, and V's health drank as enthusiastically

as if he had been the greatest benefactor of his species. As the finale,

we deposited the empty bottles and cans at the foot of the blazed tree,

and wrote our acknowledgments,—

"Gratefully received

The above;

Vide infra." On one

side, "God bless V!" and on the other, "Si vis monumen-tum, despice" and

decorating the paper with red and blue pencil marks as elaborately as time

and our limited resources permitted, we rode off with merry hearts, the

rain ceasing and the sun shining out at the same time as if to be in

unison with our feelings. Is it necessary here to implore the ascetic and

the dignified reader to be a little kind to this ebullition on our part?

It was childish, perhaps, but then what were we but "babes in the wood?"

Circumstances alter cases; and our circumstances were peculiar. We would

have gushed over a mere "bowing" acquaintance, had he come upon us in that

inhospitable valley, those melancholy woods, under those rainy skies.

Probably we might have fallen on the neck and wept over an old friend. Is

it wonderful that the "red pyramid" looked so kindly, and touched a chord

in our hearts? Two

miles farther on, the sound of a bell was heard. Jack said that it must be

the bell-horse of another pack-train; but in a few minutes a solitary

traveller, walking beside his two laden horses, emerged from the woods

ahead. He turned out to be one John Glen—a miner on his way to prospect

for gold on hitherto untried mountains and sand-bars. Here was a specimen

of Anglo-Saxon self reliant individualism more striking than that pictured

by Quinet of the American settler, without priest or captain at his head,

going out into the deep woods or virgin lands of the new continent to find

and found a home. John Glen calculated that there was as good gold in the

mountains as had yet come out of them, and that he might strike a new bar

or gulch, that would "pan out" as richly as "Williams Creek" Cariboo; so

putting blankets and bacon, flour and frying-pan, shining pickaxe and

shovel on his horses, and sticking revolver and knife in his waist, off he

started from Kamloops to seek "fresh fields and pastures new." Nothing to

him was lack of company or of newspapers; short days and approach of

winter; seas of mountains and grassless valleys, equally inhospitable;

risk of sickness and certainty of storms; slow and exhausting travel

through marsh and muskeg, across roaring mountain torrents and miles of

fallen timber; lonely days and lonely nights;—if he found gold he would be

repaid. Prospecting was his business, and he went about it in simple

matter-of-course style, as if he were doing business 'on change.' John

Glen was to us a typical man, the modern missionary, the martyr for gold,

the advance guard of the army of material progress. And who will deny or

make light of his virtue, his faith, such as it was? His self reliance,

surely, was sublime. Compared to his, how small the daring and pluck of

even Milton and Cheadle? God save thee, John Glen! and give thee thy

reward!

Glen was more than a moral

to us. He brought the Chief a letter from the Hudson Bay agent at Kamloops,

of date August 24th, informing him that our personal luggage from Toronto

via San Francisco had arrived, and would be kept for us. This was another

bit of good fortune to mark the day.

In hopes of getting to Cranberry marsh,

twenty-two miles down from the crossing, we pushed on without giving the

horses any rest except the lunch half-hour at V's Cache; But the roads

were so heavy that when within four miles of the marsh the packers advised

camping. The horses continued to go with spirit; but the long strain was

telling on them, and they had to be our first consideration. The road had

seemed to us—if not to the horses—to improve from V's Cache; but it was

still a "hard road to travel," the valley of the Thompson being almost as

bad as the valley of the Albreda. In our eighteen miles along it to-day,

there was not a mile of level. It was constant up and down, as if we were

riding over billows. Even where the ground was low, the cradle hills were

high enough to make the road undulating. The valley of the Thompson is

very narrow for a stream of its magnitude; in fact it may more fitly be

called a mountain gorge than a valley. Only at rare intervals is there a

bit of flat or meadow or even marsh along its banks. High wooded hills

rise on each side; and, beyond these, a higher range of snowy peaks, one

or another of the highest of which peeps over the woods at turns of the

river, or when the forest through which you are toiling opens a little to

enable you to see. The forest is of the grandest kind—not only the livings

but the dead; for everywhere around, lie the prostrate forms of old

giants, in every stage of decay, some of them six to eight feet through,

and an hundred and fifty to two hundred feet in length. Scarcely

half-hiding these, are broad leaved plants and ferns in infinite variety,

while the branchless columnal shafts of more modern cedars tower far up

among the dark branches of spruce and hemlock, dwarfing the horse and his

rider, that creep along across their interlaced roots and the mouldering

bones of their great predecessors.

It was not quite five o'clock when we camped ;

but the sun had set in the narrow valley, and it was quite dark before the

horses had been driven to the nearest feed, and the tent put in order for

the night. Terry set to work as usual to hurry up the tea ; but, to his

and our dismay there was no tea kettle. It had fallen by the way from the

pack to which it was tied. Jack was sure he had seen it on, four miles

back; but as "Nulla vestigia retrorsum" was our motto, whatever the loss

sustained, no one proposed to turn back and look for it; and our only

other pot, — the one used for pork and porridge boiling and all other

purposes was laid under requisition for the tea. The two frying pans had

also had their handles twisted off; but Joe tied the two handles together

and made a pair of pincers out of them that would lift one; and Terry

notched a crooked stick and made a handle for the other. Supper was

prepared with these extemporised utensils. The Doctor and Frank fried

slap-jacks and then boiled canned goose in the one pan. Terry fried pork

in the other ; and boiled dried apples in the pot before making the tea in

it. The Chief and the Secretary assisted with bland smiles and words of

encouragement, and by throwing a few chips on the fire occasionally; and a

jolly supper, between the open tent and the roaring fire, was the grand

finale.

September 22nd.—The first meal this morning,

there being only one pot, was a plate of porridge, eaten at 8.30 A.M.,

after a dip in the ice cold Thompson. Two hours after Terry announced

dejeuner a la fourchette. The Doctor and Frank roused themselves from

their second sleep to enjoy it; but Jack was absent. Not taking kindly to

the porridge, he had gone off without saying a word, in search of the

missing kettle, and service was postponed till his return.

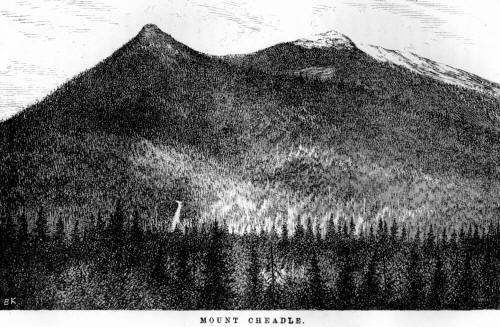

Looking round at the site

of our camp, we could see nothing on our own side of the river but a

willow thicket, and the dense forest rising beyond. On the other side, and

up stream, a snow-clad, round topped mountain looked over the lower hills.

Four or five miles down stream a lofty pyramid showed us its snowy face,

with a twin peak a little to the south, and a great shoulder also

snow-covered, extending farther beyond in the same direction. This 'biceps

Parnassus' we inferred was Mount Cheadle, and in honor of the man the camp

was dubbed 'Camp Cheadle.'

Before mid-day Jack returned in triumph with

the tea kettle— which he had found less than four miles back—slung across

his shoulders. A cup of tea was at once made in it for him as reward. The

Dr. now prepared the pudding, and when it was deposited in the pot for its

three hours boil, the bell was rung for divine service.

Just as the Secretary commenced, the pot to

the dismay of every one tumbled over. Half-a-dozen hands were

instinctively stretched out, but Terry put it right, with the coolness of

a veteran, and the service proceeded with no more trouble, except that

gusts of wind blew the smoke into our eyes, making Jack in particular weep

enough to gratify any preacher.

Dinner was ordered for four o'clock, and it

need hardly be said, the pudding was a success. It rolled from the bag on

to the plate, in the most approved fashion of oblong or rotund puddings.

The Dr. garnished it with six ferns for the six Provinces of the Dominion.

The Chief produced V's brandy, poured some over the pudding and applying a

match, it was set on the table in a blaze of blue light, that gladdened

every one with old memories.

Before sunset, the wind had blown away the

clouds and the snowy mist that had been falling up on the mountains. When

it was dark the stars came out in a clear sky, promising fine weather on

the morrow. After some general talk and calculations as to whether we

could get to Kamloops for next Sunday, in which hope weighed down the

heaviest improbabilities, all gathered round the hearthstone fire for

family worship. It was the time that we always felt most solemnized;

thankful to God for his goodness to us, praying His mercy for our far away

homes, and drawn to one another by the thought that we were in the

wilderness, with common needs, and entirely dependent on God and each

other. |