garden gate, heard the whisper of his friend,

"There is Shairp!" and saw before the door, plashed to the waist

with a long day’s fishing among the hills, the "fair-haired,

ruddy-faced, manly man," then a master of Rugby, who was to become,

later, Principal of St Andrews; and here, in every nook of the quiet

shore, the follower of the gentle craft, in the intervals of casting his

line, can recall some deed of ancient days chronicled of the spot in

Border song. If he have in his pocket the second canto of Marmion, so

much the better. Most of the region’s memories are storied there in

stirring lines, and reading these amid their native scenes the rambler

will find endless interests to repay his reverie.

In the early light the mountains behind, through which the road

descends from the outer world, appear dark and gloomy, with rain-mists

hanging low yet among them. In front, however, though the clouds are still

heavy and grey, a gleam of bright sunshine chases the shadows upon the

mountain side, and sweeps the blue surface of the lake. Revealed by it,

far along the water’s margin, their white wings gleaming against the

dark background of trees, sail the wild swans of St Mary’s, famous long

ago in

Border lays. The hills at this time of year are brown with withered

windlestrae, varied by the richer patches of russet bracken, while not

much heather is to be seen. Here, though trees are scattered but thinly

now along the lake’s edge and by the mouths of streams, roamed in bygone

times the largest stags in Scotland, with wild boars in plenty, and even

wolves. The huntsmen of the district were for long the most famous of the

Scottish archers, and the ancient character of the countryside survives in

its name of Ettrick Forest. It is the spirit rather than the detail of

this scene which has been rendered in the famous lines of Scott.

When, musing on companions gone,

We doubly feel ourselves alone,

Something, my friend, we yet may gain,

There is a pleasure in this pain:

It soothes the love of lonely rest

Deep in each gentle heart impressed.

. . . . . . . . . .

Oft in my mind such thoughts awake

By lone St Mary’s silent lake.

Thou know’st it well,—nor fen nor sedge

Pollute the pure lake’s crystal edge.

Abrupt and sheer the mountains sink

At once upon the level brink,

And just a trace of silver sand

Marks where the water meets the land.

Far in the mirror, bright and blue,

Each hill’s huge outline you may view.

Shaggy with heath, but lonely bare,

Nor tree, nor bush, nor brake is there,

Save where, of land, yon slender line

Bears thwart the lake the scattered pine.

Yet even this nakedness has power.

And aids the feeling of the hour:

Nor thicket, dell, nor copse you spy

Where living thing concealed might lie;

Nor point, retiring, hides a deli

Where swain, or woodman lone, might dwell.

There ‘s nothing left to fancy’s guess,

You see that all is loneliness.

And silence aids—though the steep hills

Send to the lake a thousand rills;

In summer tide so soft they weep,

The sound but lulls the ear asleep;

Your horse’s hoof-tread sounds too rude,

So stilly is the solitude.

On closer approach the few remaining trees by the lochside—hoary

silver birches, many-gnarled and knotted — show themselves old enough to

have shaded the ambuscade of the Scottish lover, when, according to the

ancient ballad, he came to St Mary’s Kirk to carry off his English bride

from the funeral bier. Among them, high-perched on the hillside above the

road, nestles the comfortable hostelry of Rodono—a lonely spot, after

the poet and sportsman’s own heart, and a modern rival to the more

famous inn of Tibbie Shiel.

A story which throws a lurid light upon the possibilities of life among

these hills during the feudal centuries, belongs to a spot at hand. The

Meggat Water, haunt of historic anglers, comes down here between the

hills. By the side of this stream, about a castle whose vestiges may still

be traced, hangs the tragic if somewhat uncertain legend. The place was

the stronghold of Pierce Cockburne, one of those freebooters whose lawless

deeds were, during the régime of the early Stuarts, the terror of

the Borders. As a matter of history, in the reign of James V. the ravages

of these self-made barons became so notorious that the king determined to

vindicate the law upon them. Accordingly, on a summer day in 1529, having

first taken the precaution of shutting up the greater Border lords in

Edinburgh, he made a sudden and unexpected descent upon the neighbourhood.

Here tradition takes up the tale, and relates how James, appearing before

Henderland Tower, surprised Cockburne at dinner, with short shrift hanged

the reiver and his men over their own gate, and forthwith marched, by the

path still known as the King’s Road, between St Mary’s Loch and the

Loch o’ the Lowes, and through the mountains beyond, to surprise in

similar fashion for his misdeeds Adam Scott, in his tower of Tushielaw,

and to visit afterwards with a like fate at Caerlanrig the famous Border

bandit Johnnie Armstrong. By the same tradition it is recorded that the

wife of Cockburne fled to the recesses of the Dow-glen, near the castle,

and at a place still called the "Lady’s Seat" strove to drown

in the roar of the cataract the shouts which greeted the accomplishment of

her husband’s doom. There is an ancient ballad, which was long known in

the district, said to refer to this circumstance. The pathos of its lines

suits well with the popular tradition :—

THE LAMENT OF THE BORDER WIDOW.

My love he built me a bonnie bower,

And clad it a’ wi’ lily flower;

A brawer bower ye ne’er did see

Than my true love he built for me.

There came a man by middle day,

He spied his sport and went away;

And brought the king that very night,

Who brake my bower and slew my knight.

He slew my knight, to me sae dear;

He slew my knight and poin’d his gear.

My servants all for life did flee,

And left me in extremitie.

I sewed his sheet, making my mane;

I watched the corpse myself alane;

I watched the body night and day—

No living creature came that way.

I took his body on my back,

And whiles I gaed, and whiles I sat.

I digged a grave and laid him in,

And happed him wi’ the sod sae green.

But think na ye my heart was sair

When I laid the moul on his yellow hair?

O think na ye my heart was wae

When I turned about away to gae?

Nae living man I’ll love again,

Since that my lovely knight is slain;

Wi’ ae lock of his yellow hair

I’ll chain my heart for evermair.[1]

[1 William Motherwell, in his ‘Minstrelsy, Ancient and Modern,’

ventured the hypothesis, which receives the support of Professor Child in

‘English and Scottish Ballads,’ that this lament is merely a fragment

of the English ballad, ‘The Famous Flower of Servingmen.’ The only

ground for this supposition appears to be that some nine lines of the

lament have been included in the English ballad, where they have been

awkwardly tacked on to form a quite redundant preface. The lines

appropriated are entirely at variance with the actual pleasant dénouement

of the English story, which has nothing whatever in common with the

passionate and utter grief that breathes in the Scottish ballad.]

Sir Walter Scott chose to follow this popular tradition, both in his

‘Border Minstrelsy’ and in his "Tales of a Grandfather;" and

in a note to the ballad he endeavours to furnish another link to the

story. On a broken tombstone, still lying in the deserted burial-place

which once surrounded the chapel of the castle, he deciphered, with

armorial bearings, the inscription "Here lyes Perys of Cockburne and

his wyfe Marjory." As a matter of fact, however, the Cockburne of

James V.’s time was not executed here. It is clearly set forth in

Pitcairn’s "Criminal Trials of Scotland" that he, along with

Scott of Tushielaw, was duly tried, condemned, and executed at Edinburgh.

Further, the tombstone deciphered by Scott cannot cover the famous

freebooter, since the name of the latter was not Pierce, but William,

Cockburne. Taken altogether, the probability is that tradition here has

mixed up the circumstances of more than one event. Certainly, while the

ballad may reasonably relate to the historic occurrence, the story of the

summary execution is altogether apocryphal, and the tombstone belongs to

another man. A tragedy of this nature might of course have happened at any

time in the troublous history of the Borders, and should the popular

tradition have truth in it, and be really connected with the subject of

the tombstone, it is possible that the story refers to some occurrence in

an earlier century, before the Norman prefix of "de" died out.

Professor Veitch has a fine poem on the subject of the tragedy,

entitled "The Dow Glen," in which, after describing the rocky

recess, with the burn, and its deep, dark pool, rowan-hung, he recalls the

place’s memory of "passion thrown to heaven."

As from the wife heart-broken

The waters bore the cry,

And the forest hills in echo

Woke the world’s sympathy.

Ah, me! she hears the shouting

Where she cowers beside the Linn;

Around her lord men crowding,

And all the dying din.

And now none knows her story,

Where human heart doth dwell,

But weeps the woman watching

The dead she loved so well.

Linn! in mine ear thy cadence

Hath its own peculiar fall,

As echo of a sorrow

Through time which softens all.

Clings to thy rock thy ivy

To keep faith’s memory green;

And the red rose of the briar

Glows where her love hath been.

High on the lonely hillside further on, where a few bushes wave out of

sight of the road, rises a green mound—all that is left of the chapel of

St Mary. Lonely as the spot is now, it is renowned in Border legend, has

constant mention in the ancient ballads, and has been the scene of more

than one historic incident. More tradition and poetry, indeed, probably

gathers about this ancient dependency of Melrose Abbey than about any

other kirk of its size in Scotland. It has been said that St Mary’s at

Carluke, and not the ruined fane here, was the "Forest Kirk" in

which Wallace was chosen Warden of Scotland; but the point has by no means

been finally settled. The precincts here remain, according to tradition,

the burial-place of the lovers whose heroic story is told in the ballad of

"The Douglas Tragedy," to be referred to presently. Here also,

according to some versions, is set the dramatic ending of the ballad

"The Gay Goshawk," a composition which seems to have furnished

Hogg with part of the idea for his poem of "Mary Scott," and the

machinery of which presents so curious a resemblance to that of

"Romeo and Juliet," that it would almost appear as if some

Scottish minstrel had turned Shakespeare’s play into a ballad, but with

a happier ending. A Scottish lover, debarred by the parents of his English

mistress from pressing his suit in person, sends her a letter by means of

his goshawk demanding when he can see her, as otherwise "he cannot

live ava." The lady returns the reply :—

"I send him the rings from my white fingers,

The garlands off my hair;

I send him the heart that’s in my breast;

What would my love have mair?

And at the fourth kirk in fair Scotland,

Yell bid him meet me there."

She then exacts a promise from father, mother, sister, and brothers

respectively, that if she dies in fair England they will bury her in

Scotland, performing certain memorials at three kirks there before

entombing her at the fourth. The promise exacted, she forthwith drops down

apparently dead at her mother’s knee. An old witch-wife, however, who

sits by the fire, suspects illusion :—

Says, "Drap the het lead on her cheek,

And drap it on her chin,

And drap it on her rose-red lips,

And she will speak again:

For much a lady young will do

To her true love to win."

This cruel test is applied without effect, and preparations are

therefore made for the maiden’s funeral as had been promised. Her

brothers make her a bier of cedar-wood, while her sisters sew her a shroud

of satin and silken work. The cortege then sets out.

At the first kirk of fair Scotland,

They gar’d the bells be rung;

At the second kirk of fair Scotland,

They gar’d the mass be sung.

At the third kirk of fair Scotland,

They dealt gold for her sake.

The fourth kirk of fair Scotland

Her truelove met them at.

"Set down, set down the corpse," he said,

Till I look on the dead,

The last time that I saw her face

She ruddy was and red;

But now, alas, and woe is me!

She’s wallowit like a weed."

He rent the sheet upon her face,

A little above her chin:

With lily-white cheeks and leamin’ een

She looked and laughed to him.

"Give me a chive of your bread, my love,

A bottle of your wine,

For I have fasted for your love

These weary lang days nine.

There’s not a steed in your stable

But would have been dead ere syne.

"Gae hame, gae hame, my seven brothers,

Gae hame and blaw the horn;

For you can say in the south of England

Your sister gave you a scorn.

I came not here to fair Scotland

To lie amang the meal;

But I came here to fair Scotland

To wear the silks so weel.

"I came not here to fair Scotland

To lie amang the dead;

But I came here to fair Scotland

To wear the gold so red."

Covenanter and Catholic, Scotts and Kerrs and Pringles, all sorts and

conditions of men, sleep their long sleep here at peace together. Even

that "Wizard Priest," once tenant of the chaplainry, whose story

is sung in Hogg’s "Mess John," and whose bones, according to

Scott, were "thrust from company of sacred dust," lies under the

little stone-capped mount at hand, locally known as Binram’s Cross.

Scott informs us that the kirk was wrecked by the clan of Buccleuch in the

course of a feud with the Cranstouns in 1557. The historic

circumstance is introduced as an episode in "The Lay of the Last

Minstrel," Canto II.

For the Baron went on pilgrimage,

And took with him this elvish Page,

To Mary’s chapel of the Lowes:

For there beside our Ladye’s lake,

An offering he had sworn to make,

And he would pay his vows.

But the Ladye of Branksome gathered a band

Of the best that would ride at her command;

The trysting place was Newark Lea.

Wat of Harden came thither amain,

And thither came John of Thirlestane,

And thither came William of Deloraine;

They were three hundred spears and three.

Through Douglas burn, up Yarrow stream,

Their horses prance, their lances gleam.

They came to St Mary’s lake ere day;

But the chapel was void, and the Baron away.

They burned the chapel for very rage,

And cursed Lord Cranstoun’s Goblin-Page.

Long, at any rate, it is since the last mass was sung here, and the

light went out above the altar. Knight and monk and friar rode from the

place for the last time into the darkness of oblivion three hundred years

ago. Its latest tenants, the upholders of the Covenant, themselves have

passed away, and, as the somewhat sarcastic folk-rhyme has it,

St Mary’s Loch lies shimmering still,

But St Mary’s Kirk bell’s lang dune ringing;

There ‘s naething now but the gravestane hill

To tell o’ a’ their loud psalm-singing.

The pageantry of arms, too, has bidden the spot a long farewell. From

the green ruin mound, towards the close of that fateful year in Scotland,

the ‘45, might have been seen one of the divisions of Prince Charles

Edward’s Highland army making its way southward towards Carlisle along

the old road on the further side of the loch—the last sign of war among

these hills.1 [1This tradition is recorded, from

information furnished by Lord Napier and Ettrick, in the preface by

Professor Campbell Fraser to Dr Russell’s "Reminiscences of

Yarrow."]

A pleasant place it is for the storied old-time lovers of the Douglas

ballad to rest in, visited only by sun and rain and mist, with the silent

hills watching above, and, far below, the lake murmuring in the sunshine

as it is driven into flakes of silver by the wind. Like the grave of Keats

outside the walls of Rome, "it would almost make one in love with

death to be buried in so sweet a spot."

An old grassy road slopes down the hillside eastward from St Mary’s

Kirk—doubtless the path trodden long since by priest and penitent. Half

way down its length, on the heath above the track, lie unnoticed the

remains of a still older place of burial. The existence of these remains

appears to be unrecorded; but a careful observer can still make out among

the heather several prehistoric cairns, most of them overgrown with the

peat deposit of centuries; and examination puts it beyond doubt that these

represent the resting-spot of some forgotten race.

Most appropriate here seems the loneliness which is characteristic of

all the pensive Borderside. From it one derives an impression as if the

hills and dales themselves were thinking of the days and the scenes that

have been. Amid the silence only the chip of a solitary stonebreaker’s

hammer is to be heard, as, far off upon the road, he splits for rustic

feet "fragments of some old continent." An isolated existence

the stonebreaker must lead amid this solitude; but his life among these

hills, as the reflective angler knows, will have its own pleasures. His

cares will be as few as his possessions; he will enjoy his simple fare

with an appetite a duke might envy; and his sleep will be sound of nights

after his work is done. The man, however, is compelled to own that he

knows but little of the famous places in "the Forest." He is

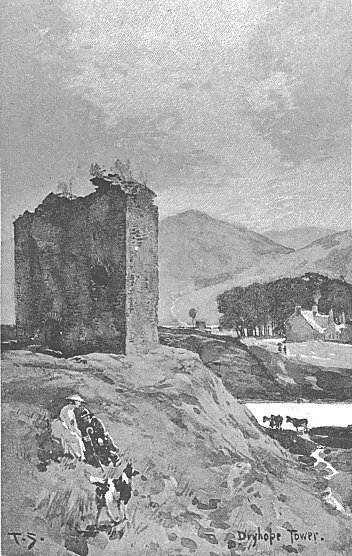

only aware that some interest is attached to Dryhope Tower, by the Dryhope

burn, a little further on.

Dryhope

Tower! The name summons to mind a vista of Border memories. The place was

the home of Mary Scott, that "Flower of Yarrow" of whom long

since sung Allan Ramsay and minor bards unnumbered. Through its low

doorway and up its broken stair her light step has trod; and her presence

amid the rude surroundings of a Border chieftain’s stronghold casts

about the spot to the present hour something of "the tender grace of

a day that is dead." Fierce and fast must have been the maiden’s

wooing by that fiery young Borderer, Walter Scott of Harden; for the

legend runs that he paid her father the significant price of "a moon

in Northumberland" to support his bride at Dryhope for a time after

her marriage. One almost wonders if she felt no feir when her

strong-handed lover carried her home to the tower which hangs yet, though

in ruins, on the edge of its own dark glen near Hawick. Certain it is,

however, that she knew how to manage that impetuous heart, for she was

first sung as the Flower of Yarrow, they say, by an English youth whom she

had saved from her husband’s doom-tree. She it was, too, who, when

provisions ran short in the larder, uncovered on the table, in place of

the smoking haunch, a pair of clean spurs—a strong hint that cattle were

to be found south of the Border. There was a fire in that gentle blood

which time had no power to cool; for sixth in descent from this union

sprang, as he himself proudly records in his all too short autobiography,

the Minstrel of Abbotsford, who was to throw its most lasting glory round

the name of Scott.

Dryhope

Tower! The name summons to mind a vista of Border memories. The place was

the home of Mary Scott, that "Flower of Yarrow" of whom long

since sung Allan Ramsay and minor bards unnumbered. Through its low

doorway and up its broken stair her light step has trod; and her presence

amid the rude surroundings of a Border chieftain’s stronghold casts

about the spot to the present hour something of "the tender grace of

a day that is dead." Fierce and fast must have been the maiden’s

wooing by that fiery young Borderer, Walter Scott of Harden; for the

legend runs that he paid her father the significant price of "a moon

in Northumberland" to support his bride at Dryhope for a time after

her marriage. One almost wonders if she felt no feir when her

strong-handed lover carried her home to the tower which hangs yet, though

in ruins, on the edge of its own dark glen near Hawick. Certain it is,

however, that she knew how to manage that impetuous heart, for she was

first sung as the Flower of Yarrow, they say, by an English youth whom she

had saved from her husband’s doom-tree. She it was, too, who, when

provisions ran short in the larder, uncovered on the table, in place of

the smoking haunch, a pair of clean spurs—a strong hint that cattle were

to be found south of the Border. There was a fire in that gentle blood

which time had no power to cool; for sixth in descent from this union

sprang, as he himself proudly records in his all too short autobiography,

the Minstrel of Abbotsford, who was to throw its most lasting glory round

the name of Scott.

Further up "the Hope," the " Auld Wa’s" represent

the keep of that daring Dick of Dryhope, who in 1596 helped Buccleuch to

rescue Kinmont Willie from Carlisle Tower, sadly, it is said, to Queen

Elizabeth’s annoyance. The story, which forms the subject of one of the

best-known historical ballads, [The ballad of "Kinmont Willie,"

in Scott’s ‘Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border.] affords a good

illustration of the manners of the Borders in the sixteenth century. On

the day of a Warden meeting, and in violation of safe-conduct, William

Armstrong of Kinninmonth had been seized and thrown into the keep of

Carlisle by Salkeld, deputy of Lord Scroope, the English Warden. Upon

hearing of the transaction, Buccleuch first tried remonstrance with Lord

Scroope and the English ambassador, and this proving futile, determined

upon the bold expedient of effecting Armstrong’s release by a midnight

raid. Mustering some two hundred horse at Morton Tower, in the Debateable

Land, an hour before sunset, he set out with scaling-ladders and

prison-breaking instruments, and reached Carlisle before daybreak. There,

his enterprise being concealed from the sentinels by a night of pitchy

darkness and a tempest of wind and rain, he forced his way in at a

postern, and found and carried off the prisoner before the garrison could

muster strength to resist. The ballad writer, in the dramatic fashion

peculiar to this class of composition, pictures Salkeld meeting the

expedition on its way, and accosting one company after another. At last he

reaches and accosts the band commanded by the doughty Dick of Dryhope.

"Where be ye gaun, ye broken men ?

Quo’ fause Sakeld; "come tell to me!"

Now Dickie of Dryhope led that band,

And the never a word of lear [learning] had he.

"Why trespass ye on the English side?

Row-footed ["Wheel-footed," equivalent to

"gallows-necked."] outlaws, stand?" quo’ he.

The never a word had Dickie to say,

So he thrust the lance through his fause bodie.

The natural beauty of the surroundings them. selves tempts the wanderer

to linger in this hollow among the low green hills. But there remains

another and subtler spell about the spot.

Of old the grey heron fed below in these narrow meadows through which

the Yarrow, freshly poured from the lake, runs, gently murmuring. Ever and

anon in ancient times the hill-foot has seen portly abbot and stalwart

earl go by; and across its "holm so green," her funeral train

"stemming the Yarrow’s silver wave," that other and scarcely

less real Mary Scott, the creation of the Ettrick Shepherd, can be

pictured, as, clad in "golden gear and cramasye," she was borne

on her bier to her unhoped-for bridal at St Mary’s Kirk with Lord

Pringle of Torwoodlee. The place is silent now. Only the kine come lowing

under the grey walls in the gloaming, and for a pennon the long grass

waves from the ruin top. Yet lhe beating here once of happy hearts, the

love, the laughter, and the sorrow that have passed away, make the sunny

knoll a haunt of pensive musings, and endue the worn stones with eloquent

regrets.

It was the spell of these things which was felt by Wordsworth, and of

which his lines remain the finest expression.

YARROW VISITED.

And is this Yarrow ?—This the stream

Of which my fancy cherished,

So faithfully, a waking dream?

An image that hath perished!

O that some minstrel’s harp were near,

To utter notes of gladness,

And chase this silence from the air,

That fills my heart with sadness.

Yet why ?—a silvery current flows

With uncontrolled meanderings;

Nor have these eyes by greener hills

Been soothed, in all my wanderings.

And through her depths, Saint Mary’s Lake

Is visibly delighted;

For not a feature of those hills

Is in the mirror slighted.

A blue sky bends o’er Yarrow vale,

Save where that pearly whiteness

Is round the rising sun diffused,

A tender hazy brightness;

Mild dawn of promise! that excludes

All profitless dejection;

Though not unwilling here to admit

A pensive recollection.

Where was it that the famous Flower

Of Yarrow Vale lay bleeding?

His bed perchance was yon smooth mound

On which the herd is feeding;

And haply from this crystal pool,

Now peaceful as the morning,

The water-wraith ascended thrice—

And gave his doleful warning.

Delicious is the lay that sings

The haunts of happy lovers,

The path that leads them to the grove,

The leafy grove that covers:

And pity sanctifies the verse

That paints, by strength of sorrow,

The unconquerable strength of love;

Bear witness, rueful Yarrow I

But thou, that didst appear so fair

To fond imagination,

Dost rival in the light of day

Her delicate creation.

Meek loveliness is round thee spread,

A softness still and holy;

The grace of forest charms decayed,

And pastoral melancholy.

That region left, the vale unfolds

Rich groves of lofty stature,

With Yarrow winding through the pomp

Of cultivated nature;

And, rising from those lofty groves,

Behold a ruin hoary!

The shattered front of Newark’s towers,

Renowned in Border story.

Fair scenes for childhood’s opening bloom,

For sportive youth to stray in;

For manhood to enjoy his strength;

And age to wear away in!

Yon cottage seems a bower of bliss,

A covert for protection

Of tender thoughts, that nestle there—

The brood of chaste affection.

How sweet, on this autumnal day,

The wildwood fruits to gather,

And on my true-love’s forehead plant

A crest of blooming heather!

And what if I unwreathed my own!

‘T were no offence to reason;

The sober hills thus deck their brows

To meet the wintry season.

I see—but not by sight alone,

Loved Yarrow, have I won thee;

A ray of fancy still survives—

Her sunshine plays upon thee!

Thy ever-youthful waters keep

A course of lively pleasure;

And gladsome notes my lips can breathe,

Accordant to the measure.

The vapours linger round the heights,

They melt, and soon must vanish;

One hour is theirs, nor more is mine—

Sad thought, which I would banish,

But that I know, where’er I go,

Thy genuine image, Yarrow!

Will dwell with me—to heighten joy,

And cheer my mind in sorrow.

From the home of Mary Scott, a mile to the east by the side of

Blackhouse Farm, the Douglas Burn comes down to join the Yarrow, and the

murmur of its waters is the "Open, Sesame," to another cluster

of old-world associations. The quiet farm-house itself, at the glen mouth,

was the home of William Laidlaw, the amanuensis and friend of Sir Walter

Scott, and author of the simple and beautiful verses, ‘Lucy’s Flittin’;’

and on the Blackhouse heights above it was that for ten years the Ettrick

Shepherd tended his flocks. It was on one of these heights, the Hawkshaw

Rig, past which the Blackhope burn comes down to join the Douglas, that

upon a summer day in 1796 an interesting thing happened. As the young

herdsman was watching his sheep, a half-daft wanderer of the countryside,

named Jock Scott, lying near him on the heather, recited a marvellous poem

called ‘Tam o’ Shanter,’ made, said the reciter, by an Ayrshire

peasant, lately dead, of the name of Robert Burns. As he listened, it is

said, big tears of joy and surprise rolled down Hogg’s quivering cheek.

Again and again he had the poem repeated till he knew by heart every word

of it; and forthwith he resolved to serve himself the successor of the

ploughman poet. Thanks to the old songs and ballads crooned to his

childish ears by his mother at Ettrick Hall, "he could tell more

stories and sing more songs," he felt sure, "than ever ploughman

could in the world." Thus casually fell the spark which set the

lonely herdsman’s heart on fire. Well, however, might that herdsman

sing, spending the long days, as he did, alone amid such scenes and

memories, and within the hearing of so many traditions. It would be

difficult in all broad Scotland to find a spot more fit for the dreaming

of a poet.

Two miles up the Douglas water, in the very heart of the quiet hills,

lies the tower of the Good Lord James, who strove to carry the heart of

the Bruce to the Holy Land. The Douglases were early settled here. Sir

John, eldest son of William, first Lord Douglas, is recorded by Hume of

Godscroft, the family historian, to have sat as baronial lord of Douglas

Burn, in a parliament of Malcolm Canmore, held at Forfar; and here the

companion of Bruce was wont sometimes to retire to gather fresh forces for

the cause of the king. A crumbling ruin now, the home of the Border lord

is abandoned to the last neglect. Within the walls which cradled that

haughty race are kennelled a shepherd’s dogs, and rubbish and filth

cover the hearth and threshold of the Black Douglas. A silent reproach

exists in the aspect of the broken ruin, desecrated by mean uses,

unvisited and uncared-for in its decay.

From this tower it was, as the ballad of ‘The Douglas Tragedy’

tells, that Fair Margaret was carried off by her lover. A mile further up

the solitary glen stand seven great stones, marking, it is said, the spot

where Lord William alighted and slew the lady’s seven pursuing brothers;

and the bridle road, one of the disused mediaeval paths from tower to

tower, which the fleeing lovers are said to have followed, can still

easily be traced across the hills, The words of the ancient composition

possess a strange vividness when read with a knowledge of the locality,

and at the foot of these grey walls.

THE DOUGLAS TRAGEDY.

"Rise up, rise up, now, Lord Douglas," she

says,

"And put on your armour so bright;

Let it never be said that a daughter of thine

Was married to a lord under night!

"Rise up, rise up, my seven bold sons,

And put on your armour so bright,

And take better care of your youngest sister,

For your eldest’s away the last night!"

He ‘s mounted her on a milk-white steed,

And himself on a dapple gray,

With a bugelet horn hung down by his side,

And lightly they rode away.

Lord William lookit o’er his left shoulder

To see what he could see,

And there he spied her seven brethren bold

Come riding o’er the lea.

"Light down, light down, Lady Marg’ret," he

said,

And hold my steed in your hand,

Until that against your seven brethren bold,

And your father, I make a stand."

She held his steed in her milk-white hand,

And never shed one tear,

Until that she saw her seven brethren fa’,

And her father hard-fighting, who loved her so dear.

O, hold your hand, Lord William!" she said,

For your strokes they are wondrous sair;

True lovers I can get mony a ane,

But a father I can never get mair."

O, she ‘s ta’en out her handkerchief,

It was o’ the holland sae fine;

And aye she dighted her father’s bloody wounds

That were redder than the wine.

O choose, O choose, Lady Marg’ret," he said;

O whether will ye gang or bide?"

"I’ll gang, I’ll gang, Lord William," she said; "

For you have left me nae other guide."

He’s lifted her on a milk-white steed,

And himsel’ on a dapple grey,

With a bugelet horn hung down by his side,

And slowly they baith rude away.

O they rude on, and on they rade,

And a’ by the light o’ the moon,

Until they came to yon wan water,

And then they lighted down.

They lighted down to tak’ a drink

O’ the spring that ran sae clear;

And down the stream ran his gude heart’s blood,

And sair she began to fear.

"Hold up, hold up, Lord William," she said,

"For I fear that you are slain!"

"‘T is naething but the shadow o’ my scarlet cloak

That shines in the water sae plain."

O they rude on, and on they rade,

And a’ by the light o’ the moon,

Until they cam’ to his mother’s ha’ door,

And there they lighted doun.

"Get up, get up, lady mother," he says,

Get up and let me in

Get up, get up, lady mother," he says,

"For this night my fair lady I’ve win.

"O, mak’ my bed, lady mother," he says,

"O, mak’ it braid and deep,

And lay Lady Marg’ret close at my hack,

And the sounder I will sleep."

Lord William was dead lang ere midnight,

Lady Marg’ret lang ere day;

And all true lovers that go thegither,

May they have mair luck than they!

Lord William was buried in St Mary’s Kirk,

Lady Marg’ret in Mary’s quire:

Out o’ the lady’s grave grew a bonnie red rose,

And out o’ the knight’s a brier.

And they twa met, and they twa plat,

And fain they wad be near;

And a’ the world might ken right weel

They were twa lovers dear.

But bye and rude the Black Douglas,

And wow but he was rough!

For he pulled up the bonnie brier,

And fang it in St Mary’s Loch.

As one lingers in the silent glen, the scene of this strange romance

and of its tragic outcome, a "breath of the time that has been"

seems to hover about it, with the sadness of these old forgotten days.