|

After the great crisis—what then? The excitement, the enthusiasm, the

crowded meetings, the cheers that greeted them were over—the time had

come to face the privations, the loss of their old homes and of their

churches. Other roofs must cover their heads, and their preaching, for a

time, must be done under difficult, and sometimes nearly impossible,

conditions. The sacrifices, the devotion, the grandeur of those who were

prepared to lose everything rather than yield unto Caesar the things

that belonged to God must in these years of paler spiritual faith stir

the blood of their descendants. Mr Gladstone said: "As to the moral

attitude of the Free Church, scarcely any word weaker or lower than that

of majesty is, according to the spirit of historical criticism, justly

applicable," and the late Duke of Argyll described those

spiritual-minded ministers as being "the best and greatest men I ever

knew."

My story is almost told. Dr Duncan returned to Ruthwell only

to leave his old home shortly afterwards for ever ; the manse, that for

forty years had been his home,- and the church where he had ministered

to his people. He walked round his garden for the last time, bidding

farewell to every tree and shrub; he crossed the little wooden bridge,

went through the gate that led to the churchyard and meditated there

alone. What thoughts must have lingered in his heart! The last load of

furniture was gone;s he looked for the last time at the desolate rooms,

and saw the cinders growing grey in the grate: he turned and left it

all. The latch of the gate clicked behind him as he passed out from the

old life full of sweet memories, to begin the new life when he was in

his seventieth year. There was no house for them in the village, but an

old parishioner was good enough to share her house with her minister and

his wife. It is sad and painful to dwell on this part of his life. It

meant many bitter partings with old parishioners, who did not follow in

his footsteps, but remained behind in the Established Church, for it was

only about half the church-going population that "went out" with him. It

must have been a hard wrench to see those who had been with him breaking

away and going in the opposite direction.

It was useless to look for a

site for the Free Church near Ruthwell, as the landed proprietors were

against the movement. He, therefore, had to turn his eyes further

afield. A suitable place was found at Mount Kedar, though it was

situated some distance from the village of Ruthwell. He preached, in the

meantime, in a barn fitted up as a temporary place of worship; and he

used also to go every other Sunday many miles along the sands of the

Solway to Cterlaverock to preach in the open air. His well-known figure

was to be seen whatever the weather might be, and these open-air

services were a striking proof of the spirit of the people, for they

would come from great distances to hear him.

DR DUNCAN OF RUTH WELL

"I heard on

the side of a lonely hill,

The Free Kirk preacher's wrestling prayer;

Blue mist, brown muir, and a tinkling rill,

God's only house and

music there.

And aged men, in mauds of grey,

Bare-headed stood

to hear and pray.

Is it to pomp and splendour given

Alone to

reach the throne on high?

The hill-side prayer may come to heaven

From plaided breast and up-cast eye."

Dr Duncan eventually took up his

residence in a labourer's cottage, which is still standing on the

highway. It contains two small rooms, and his wife says that though it

was damp and some of the ceiling was broken, they were thankful to get

into a place of their own and felt "as if they had found a palace." He

was very happy there and set to work at once to make the garden nice. A

story is told about him in his little cottage. The writer says, speaking

of Dr Duncan, "I saw the fine old gentleman in his roadside cottage

about the year 1846. He entertained his company, a few ministers in the

neighbourhood, with the polished courtesy of the old school. Dinner

over, he said: "Will you go into the drawing-room, gentlemen?" His

friends gazed at each other and wondered what he could possibly mean.

Opening the back door of the cottage he said: "My drawing-room is the

great drawing-room of nature." Through declining health and the too

frequent calls made upon his strength his family were anxious for him to

remove, for the cottage was too damp and cold for him, and it was

generally thought by his relations and friends that his health required

great care. Pressure was put upon him to go to Edinburgh where he would

find plenty of work to do in connection with the Church. He was

reluctant to go; he said: "If they take me from my people, they may just

lay me on the shelf. My energies, such as they are, are gone, and I

really think that if I be transplanted I shall wither and die." It was

expedient and advisable, however, for him to go away and live under more

healthy conditions, and give up for a time an active part in the parish.

But he bitterly felt moving from the active part he had taken. "Must I

slip off at last like a knotless thread? I have no doubt that I could

find something to do in Edinburgh, if I had faith for it, but I feel

that I am too old to transplant." The short time he spent in Edinburgh

was very sad for he felt the separation from his people, and his heart

was at Ruthwell. When his health improved he started on a campaign in

Liverpool and Manchester to collect funds to finish the church and manse

at Mount Kedar. He seriously overtaxed his strength by the amount of

work he did; he preached con^ stantly to crowded congregations, and

devoted himself heart and soul to interesting everyone in the Free

Church. No warnings from friends who knew that he was doing far too much

turned him away from the work he had to do, and he very nearly succeeded

in collecting the sum required. With a joyful heart he hastened back to

Ruthwell, and his old parishioners, both those who left the Church with

him and those who did not, joined in welcoming him. Touching and

pathetic interviews passed between them; he made a house to house

visitation; he specially gave up much of his time to the sick and dying;

he brought comfort to the afflicted. He went to Mount Kedar to

superintend the work there—his activity seemed as great as ever. It was

the bright flickering of the candle before the end. He was seen in the

churchyard, lingering, wrapt in thought, his horse tied to the gate.

What memories the scene of his old home must have brought back to him,

of days of youth and vigour, and healthy, glowing life; the old house

where he had spent so many happy years and where his children had been

born. A few days later he was holding a service in the house of an

elder of the Established Church, which shows that there was no

bitterness of feeling. The little room was crowded; the sun went down

leaving the room in semi-darkness; he lit a candle; he seemed calm and

quiet—there was no trace of excitement in his manner. As the light of

the candle did not reach the Bible he had in his hand, he looked round,

and reaching a jug from a shelf placed the candle on it so that the

light should fall on his book. The 121st psalm was sung; he knelt and

offered up a prayer and then gave out his text, from the third chapter

of Zechariah, ninth verse: "For behold the stone." Shortly afterwards

his voice sounded strange. It was thought at first that emotion choked

his utterance; his limbs trembled, his voice was lowered to a whisper,

and he sank back into a chair. It seemed at this meeting that

he was at the very gate of heaven. The people were stirred to their very

depths, and many a tear stole silently down the faces of those present.

He was carried by devoted people from the room, and driven as carefully

as possible to Comlongon Castle, the residence of his brother-in-law. He

was conscious of all that was going on for he was heard to say, looking

up at the stars, "Glorious! most glorious!" He was never able to utter

more than a few words afterwards. His wife and children were too late to

see him, and he died peacefully before they arrived. They laid his body

to rest in the quiet churchyard close to the scenes of his many

labours—the gravestone is against the wall that separates the churchyard

from the manse garden.

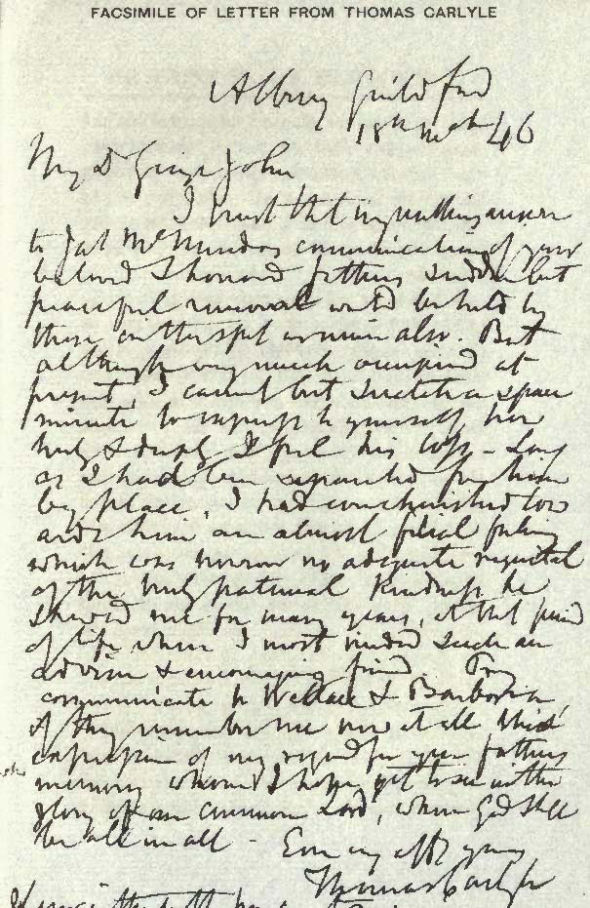

Carlyle, who was so often at the manse, wrote

to one of Dr Duncan's sons to express his sympathy.

Albany, Guilford,

18th March, '46.

My dear George John,—I trust

that my mother's answer to Jas. M'Murdo's communication of your beloved

and honoured father's sudden, but peaceful removal, would be held by

those on the spot as mine also. But although very much occupied at

present, I cannot but snatch a spare minute to express to yourself how

truly and deeply I feel his loss. Long as I had been separated from him

by place, I had ever cherished towards him an almost filial feeling

which was, however, no adequate requital of the truly paternal kindness

he showed me for many years, at that period of life when I most needed

such an adviser and encouraging friend. Pray communicate to Wallace and

Barbara, if they remember me now at all, this expression of my regard

for your father's memory, whom I hope yet to see in the glory of our

common Lord, when God shall be all in all.—Ever very affectionately

yours,

Thomas Carlyle.

It was a fitting end to a long

and useful life. He died at his post. His memory still lives in the

hearts of the people at Ruthwell—his love for mankind, his indulgence

towards poor suffering humanity, his whole personality breathed forth a

spirit of love towards all men. His tombstone records how he was

"distinguished through life by many gifts and graces," how "his last

years were his best," and "death found him a tried soldier of the Cross,

cheerfully enduring hardness and contending earnestly." |