|

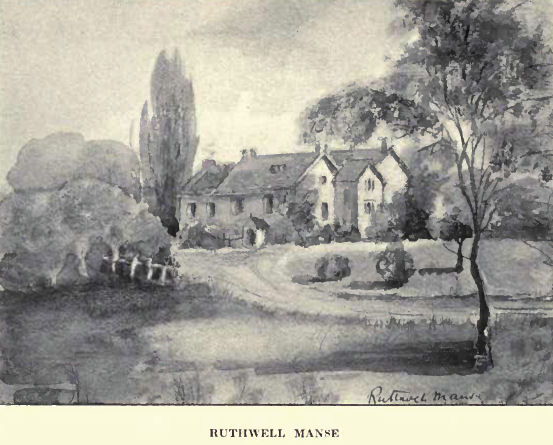

Mr Duncan's return, after this long absence from home, was a very happy

event. He had often sighed for his beloved village, and the name of

Ruthwell was written upon his heart. Turn aside with him from the

village, through the shady garden beyond the threshold, right into the

heart of the manse, and you will be greeted by a spirit of rest and

peace, a sweet and fragrant atmosphere of happy home life. It was here,

surrounded by his wife and family, that he showed to the greatest

advantage. Imagine what excitement his return from London meant to them

after those long weeks of absence, what talks and discussions and

questionings must have arisen in those long northern evenings about

where he had been, and whom he had seen, and what he had done. He must

have laid his head upon his pillow with thankfulness, and felt that

success had at last been achieved. Many occupations awaited him, his

parish was eagerly watching for his return, there were consultations

with the elders, parish affairs to look into, the Savings Bank to attend

to, and his garden to give him healthful exercise after his life in

London. Ruthwell manse was the centre of a cultivated, interesting

group. Mr Duncan had the power of drawing people to him to a remarkable

extent. Notwithstanding all the difficulties of communication in those

days, eminent men of letters, antiquarians, both English and foreign,

and philanthropists were frequently within his gates. The hospitality of

that simple household, where there was not a shadow of false taste or

decoration, but a beautiful simplicity, was much appreciated by all who

visited there —indeed so much so that it was frequently far too full of

guests for the comfort of the family, the minister and his wife having

often to give up their own rooms and slip down to the cottage at

Clarencefield, where lived Mrs Craig, Mrs Duncan's mother, returning in

time for breakfast, so that no one knew of their absence. Surely this

was the very incarnation of hospitality! The conversation, it is

recorded, was excellent, illumined by the gifted people assembled there.

The minister himself presided with his vigorous and comprehensive mind,

his ready sympathy, his broad and generous views, and his flow of

interesting conversation. Mrs Duncan would sit near listening in her

high-backed chair, her gentle intelligent face aglow with interest,

dressed in the somewhat ceremonious fashion of the day, her neatly

coiled hair nearly concealed by her white cap, looking the picture of

domestic peace. She never appeared to be in a hurry, and yet everything

was sweetly trim and neat. Speaking of her reminds me of a very

important part of the life at Ruthwell manse which I should have

mentioned earlier, and one in which her influence was much felt. Mr

Duncan took pupils and educated them with his own children and those of

his brothers.

James Frederick Ferrier, the metaphysician, was one of

them, and in a letter to one of Mr Duncan's sons in 1848 he recalls some

of the happy days he spent there in his youth. "Then was the golden

age of our existence. ... I reverence the good sense which pervaded

their parental management of us, and which showed itself in nothing more

than this that they permitted us, so long as we did no harm, to wander

at our own sweet will. A deal of mischief is done by eternally yirking

at children. We often made a slide on the winter mornings at four

o'clock when the air was sweet (we did not think it cold then), when the

grass was powdered with diamond dust, and the moon had been strangely

wheeled back into the opposite region of the sky. Do you remember these

things anno domini 1818 or 1817, or still earlier in the year of

Waterloo when every nettle became a Frenchman, and the peat stack was

carried at the point of the bayonet . . . ? " Miss Haldane says, in her

Life of Ferrier, that he always spoke of Ruth well and the time he spent

there " with every indication of gratitude for the instruction which he

received . . . and always expressed himself as deeply attached to the

place where such a happy childhood had been passed. . . ." Robert

Mitchell, Carlyle's great friend, was for many years the principal

tutor. It was to him, during his residence there, that Carlyle wrote so

many of his early letters, letters in which he poured out to his friend

his most intimate thoughts— the story of his aspirations—his rebuffs. He

soon became a favourite guest. Duncan was not slow to find out the great

genius of his young visitor. Even in those early days he had begun to

attract attention. Carlyle's friends at this time were few, and those

few were not influential. One of the first letters of introduction he

ever received was from Mr Duncan to Mr, afterwards Sir David Brewster.

This must have been of great value to the young student in the early

stage of his career, and, when he received it, he wrote to his friend

Mitchell to say, " with regard to your most kind minister, my

circumstances qualify me but poorly for doing any justice to the

feelings which his conduct is calculated to excite." Later on, when it

was Mr Duncan's great privilege to still further help him, he again

writes to Mitchell: " To Mr Duncan, who possesses that rare talent of

conferring obligations without wounding the vanity of him who receives

them, and the still rarer disposition to exercise that talent, all

gratitude is due on my part." Some years later, I think it was in 1870,

Mr George Duncan, the grandson of Mr Duncan, wrote to Carlyle. In an

enthusiastic letter breathing youthful ardour and hero-worship in ever)7

line, he asks Carlyle for guidance on the subject of prayer, and

addresses him in the following words: "You are my minister, my only

minister, my honoured and trusted teacher." He also goes on to tell him

that he has in his possession a work of his that Carlyle had presented

to his grandfather with this inscription on the fly-leaf: "To the Revd.

Dr Duncan from his grateful and affectionate friend Thomas Carlyle." The

letter is to be found at length with the reply in Froude's Life of

Carlyle, and the allusion to Dr Duncan in the answer is precious to all

his descendants. " Your grandfather was the amiablest and kindliest of

men; to me pretty much a unique in those young days, the one cultivated

man whom I could feel myself permitted to call friend as welhyNever can

I forget that Ruthwell manse, the beautiful souls, your grandmother,

your grand-aunts, and others who then made it bright to me—all vanished

now—all vanished."

Two poets, Hogg, the Ettrick Shepherd, and Grahame,

Bard of the Sabbath, were frequent guests. Hogg, with all his quaint

ways and sayings, must have been a very warm-hearted, lovable being, his

genius shining through his rough exterior. He produced songs and verses

with the greatest facility, but it was The Queen's Wake that established

his reputation. His was rare genius, indeed. The son of a shepherd and

himself a child of that humble calling, he had taught himself to read on

the hillside while taking care of his sheep. He had gone step by step to

work, and his public had been very gradually won. He has given some of

the sweetest songs to the Scottish language that it possesses, and his

short poem to the lark comes back to me as I write:

"Bird of the wilderness,

Blithesome and cumberless

Sweet be thy

matin, o'er moorland and lea!

Emblem of happiness,

Blest is thy

dwelling place:

O! to abide in the desert with thee!

Wild is thy lay and loud,

Far in the downy cloud;

Love gives it

energy, love gave it birth, .

Where, on thy dewy wing,

Where art

thou journeying?

Thy lay is in heaven, thy love is on earth."

Hogg's position in life altered very much as he became famous. Sir

Walter Scott was his intimate friend, and he was much feted in Edinburgh

and in London. His marriage to Miss Phillips was celebrated by Mr

Duncan, who was connected with her by marriage. On his death, Wordsworth

wrote some verses to his memory:—

"The mighty minstrel

breathes no longer,

'Mid mouldering ruins low he lies,

And death

upon the Braes of Yarrow

Has closed the shepherd poet's eyes."

James Grahame was a very modest, quiet man and brought almost too much

humility into his daily life. He even published The Sabbath anonymously,

as he was doubtful whether his wife would appreciate it, and he did not

acknowledge the authorship of the inspiring poem until he found her

enraptured with its beauty. Grahame had been both an advocate and a

clergyman. A contemporary says of him: "Never was a purer or gentler

mind than his, never poet more beloved." His visits were a delight to

them all at Ruthwell, and Mr Duncan loved the calm beauty of The

Sabbath, and often quoted these beautiful lines :

"How

still the morning of the hallow'd day!

Mute is the voice of rural

labour, hush'd

The plough boy's whistle, and the milkmaid's song,

The scythe lies glitt'ring in the dewy wreath.

Of tedded grass,

mingled with fading flowers,

That yestermorn bloom'd waving in the

breeze:

* * * * *

With dove-like wings

peace o'er yon village broods.

The dizzying mill wheel rests ; the

anvil's din

Hath ceased, all, all around is quietness.

Less

fearful on this day, the limping hare

Stops, and looks back, and

stops, and looks on man,

Her deadliest foe. The toil-worn horse, set

free,

Unheedful of the pasture, roams at large;

And, as his stiff,

unwieldy bulk he rolls,

His iron-arm'd hoofs gleam in the morning

ray.

Hail Sabbath! Thee 1 hail, the poor man's day:

The pale

mechanic now has leave to breathe

The morning air free from the

city's smoke."

To turn from poets to practical people, obert Owen, the

great social reformer, and at one time a partner of Bentham, visited

Ruthwell on more than one occasion, drawn thither by Mr Duncan's

interest in philanthropic matters. For a quarter of a century Owen drew

public attention to his labours and experiments in social and economic'

matters at New Lanark, where he initiated many much-needed reforms into

factory life. His favourite theory was that "Circumstances form

character," and it was with this object in view that he started his

infant school. He also started a store at which the poor could purchase

provisions and clothing twenty-five per cent, cheaper than elsewhere,

and which should yet yield a good profit. New Lanark possessed a public

kitchen and dining-room, and he calculated that his combination saved

the people between £4000 and £5000 a year. He worked hard to better the

conditions of apprentices, whose long hours and insufficient food

touched him deeply. In alluding to their condition he says : " Perish

the cotton trade ; perish even the political superiority of our country

if it depends on the cotton trade, rather than they shall be upheld by

the sacrifice of everything valuable in life by those who are the means

of supporting them." His factory was an illustration of how an

enterprise could show profit and yet, at the same time, improve the

conditions of labour. Interested persons came from all over the world to

New Lanark to witness for themselves the working of Owen's theories—

theories that would be considered advanced even to-day, and which were

yet brought into practice nearly one hundred years ago.

Spurzheim,

then attracting a great deal of attention as the expounder of

phrenology, was lecturing in many of the principal towns in the United

Kingdom, and gaining many adherents. He advocated his theories with the

greatest enthusiasm and eloquence. Finding his way to the manse in his

travels northwards, he collected round Mr Duncan's fireside ready

listeners to his theories. Miss Hamilton, the authoress of The Cottagers

of Glenburnie, was a great favourite with Mr Duncan, her stories of

Scottish life and manners always delighting him. One of his own works,

The Cottage Fireside, has been compared to this work. The Quarterly

Review gives it a most favourable criticism, saying, "In point of

genuine humour and pathos we are inclined to think that it fairly merits

a place by the side of The Cottagers of Glenburnie, while the knowledge

it displays of Scottish manners and character is more correct and more

profound." Miss Hamilton's house in Edinburgh, though offering the

simplest hospitality, attracted everybody; interesting and cultivated

people were always to be found to discuss there the topics of the day

with their clever hostess. It was Jeffrey who is supposed to have said

to her, speaking of the feminine in literature, " That there was no

objection to the blue stocking provided the petticoat came low enough

down." Geologists came from all parts to discuss Mr Duncan's

discoveries. Such great men as Sir David Brewster, Dr Buckland,

Sedgewick, Murchison, and Poulet Scrope found their way to that retired

parish. Sir David Brewster brought the light of his genius into many a

discussion, and was a very intimate and valued friend. He had devoted

twenty-two years of his life to the Edinburgh Encyclopaedia, and it may

be said that the whole of his long life was given up to scientific

research. The subjects of his works are various and far reaching, and

the very titles are an indication of the activity and development of

this wonderful mind. For a short time Sir David Brewster was a minister

of the Church of Scotland, but the nervousness he felt in preaching made

this a very painful profession for him to pursue. His researches and

discoveries in science seemed only to strengthen his faith. He was to

the end of his life a tenacious upholder of the evangelical doctrines of

the Church, and he walked in the great procession of '43.

Dr Buckland, the Dean of Westminster, and a great geologist, also

found his way to Ruthwell—a high tribute from this busy man; he came to

inquire and went away convinced of the value of Mr Duncan's geological

discoveries. He found, like so many other people, the charm of visiting

that happy household, and went away astonished at the knowledge and

originality of the minister. Sedgewick, too, with his tall striking

figure, thick shaggy hair and dark penetrating eyes, eyes which would

light up with a glow of animation when talking, came to inquire into the

genuineness of the Testudo Duncani—of which we shall have to speak in

the next chapter. That lion of the Scottish Church, the brilliant

Chalmers, with all his great and magnificent ideas about the elevation

of the working classes, his depreciation of the false principle of the

ordinary poor laws, and his enthusiasm for the self-governing power of

the Church, was another visitor. He always prophesied that pauperism

would one day seriously endanger the state, and over and over again, in

his works in different forms, this sentiment appears. "The remedy

against the extension of pauperism does not lie in the liberties of the

rich; it lies in the hearts and habits of the poor . . . teach them to

recoil from pauperism as a degradation." In Dr Chalmers' diary, there is

a short entry in 1822: " Got to Ruthwell after four. I again preached at

5.30 to a well-filled church. The congregation of a very interesting

moral aspect. After tea called on Mr Duncan's mother, who lives in an

elegant cottage which Mr Duncan has raised up on his premises. She is a

fine old lady, and an aunt of Mr Duncan's lives along with her. He has

forty acres of glebe, and out of it has assumed a policy of five or six

acres round his house, which he has transformed from a moor into a very

beautiful and gentlemanly pleasure ground, consisting of gardens, lake,

and a number of well-disposed trees. Had an hour before supper to wind

up my narrative and letters, obtained most satisfactory information from

Mr Duncan, and threw myself into my bed between twelve and one." Dr

Chalmers' social qualities are best described in the memoirs of Mrs E.

Grant of Laggan. " You ask me to tell you about Dr Chalmers. I must tell

you first, then, that of all men he is the most modest, and speaks with

undissembled gentleness and liberality of those who differ from him in

opinion. Every word he says has the stamp of genius ; yet the calmness,

ease, and simplicity of his conversation is such that to ordinary minds

he might appear an ordinary man. I had a great intellectual feast about

three weeks since. I breakfasted with him at a friend's house, and

enjoyed his society for two hours with great delight. Conversation

wandered into various channels, but he was always powerful, always

gentle, and always seemed quite unconscious of his own superiority." Mrs

Grant goes on to compare Scott and Chalmers, saying: "I could not help

observing certain similarities between these two extraordinary persons,

the same quiet unobtrusive humour, the same flow of rich, original

conversation, easy, careless, and visibly unpremeditated : the same

indulgence for others, and readiness to give attention and interest to

any subject started by others. There was a more chastened dignity and

occasional elevation in the Divine than in the Poet, but many resembling

features in their mode of thinking and manners of expression."

Another

friend and countryman of Mr Duncan, a native of Annan, Edward Irving,

was a frequent visitor, and held the warmest place in his affections,

both in his youth and in the days when he was attracting the whole of

London to his chapel. I think what Carlylc said of Irving brings him

before one's eyes better than any other or longer description.

What the Scottish uncelebrated Irving was, they that have only seen the

London celebrated (and distorted) one can never know. His was the

freest, brotherliest, bravest human soul mine ever came in contact with.

I call him on the whole the best man I have ever (after trial enough)

found in this world or now hope to find." The celebrated founder of the

Irvingite Church was tutor to Miss Jane Welsh in her youth, and no

separation or change of circumstances ever interfered with their

friendship and affection for each other. It was at one time thought that

this friendship would have a tender ending, and Mrs Carlyle was very

much attached to him.

It was a painful time for Mr Duncan in 1833

when, owing to his position in the Presbytery, he was obliged to take an

active part in the deposition of Irving; but the Supreme Court of the

Church ordained it, so he was obliged to carry out their injunctions.

Mrs Oliphant, in her Life of Irving, shows no bitterness towards him,

and speaks of him " as a man of universally acknowledged eminence and

high character." Only those who knew Mr Duncan's kindly nature realised

what a painful, sad time this was in his life.

Dr Andrew 'Thomson, one

of Scotland's greatest churchmen, carried on a correspondence with Mr

Duncan and visited him from time to time. He was conspicuous for

following his own line, and was supposed to glory in conflict. He went

against the whole Church in refusing to have a funeral service for

Princess Charlotte, maintaining that "all such sermons are repugnant to

the Presbyterian system and dangerous in themselves from the tendency to

degenerate into sycophantic eulogy." Dean Ramsay, in his interesting

book of Scottish stories, repeats one that Dr Andrew Thomson loved to

tell: "A clergyman in the country had a stranger preaching for him one

day, and meeting the beadle he said to him, Well, Saunders, how did you

like the sermon to-day ?' 'I watna, sir, it was rather o'er plain and

simple for me. I like thae sermons best that jumbles the joodgement and

confounds the sense: od, sir, I never saw one that could come up to

yoursel' at that.'"

William Gillespie, who was at Edinburgh University

with Mr Duncan, kept up the old friendship that started in their student

days. Gillespie, in common with a very large number of the Scottish

clergy, rebelled against the order that Queen Caroline's name should be

crossed out of the prayers for the Royal family. Queen Caroline became a

party question, and the clergy were divided into those who prayed

fervently for her and those who did not. The thoroughgoing Whigs made it

a point of faith to do her honour, while others considered her a

disgrace to the country. When Gillespie was chaplain to the Stewartry of

Kirkcudbright Yeomanry Cavalry, the order came to omit her name. The

Commandant, who appeared to be a little doubtful of Gillespie's

attitude, wrote and asked him what he intended to do about the Queen,

and his reply was a very evasive one. When the usual prayer for the

Royal family was in progress, he said "Bless also the Queen," and on

this he was told to consider himself under arrest.

In those days

people "drank tea" and "supped," and supper was the convivial meal of

the day. It was this simple repast that drew the busy household-together

after the work of the day was over; the evening hour brought out and

deepened the spirit of companionship and sociability. It was then

conversation was at its best; it was then the employments and

occupations of different members of the household were discussed; the

progress of the pupils, the literature and politics of the day. In the

summer evenings the windows were thrown open to let in the fresh breezes

of the Solway, and Mr Duncan loved to point out to the inmates of the

room, the marvels and mysteries of the heavens, for he had a deep

perception of all that was beautiful in nature. When the evening drew to

its close the servants were summoned, those faithful old servants who

were such a feature of Scottish life in that day. There was a vein of

good feeling running through the intercourse between both master and

servant, rendering it a most intimate and agreeable one. One imagines

the hush when they were seated, his countenance illumined by devotion

when he opened the Bible, the simple prayers, and his melodious voice

blessing the household before parting for the night. These were peaceful

days over which, however, the gathering clouds of the coming struggle in

the Church were beginning to cast their shadows. |