|

The most notable work of Mr Duncan's life and the one with which his

name will ever be honourably associated, and which will give him an

assured place among the benefactors of mankind, was the "System of

Savings Banks"—of which he was the founder. Always keenly interested in

the conditions of the poor, he was, as we have seen, very much averse to

the poor laws. While studying this all-important subject, he came across

a paper called Tranquillity by Mr John Bone, dealing with the very

subject he was so much interested in, viz., a plan for gradually

abolishing the poor rates in England, and a theoretical scheme for

establishing a bank for the savings of the industrious. The germ of the

idea which he afterwards successfully developed, was contained in this

publication. It was of too visionary and unpractical a nature in its

present form, but he felt, when he had separated the real from the

ideal, that upon the substance remaining he could build up a practical

scheme for encouraging the working classes to provide for their old age

or for the proverbial rainy day. His maxim was to help the people to

help themselves ; and not merely to relieve poverty, but to cure

pauperism; or, to quote the excellent words of Dr Chalmers : "If you

confine yourself to the relief of poverty, you do little. Dry up, if

possible, the springs of poverty, for every attempt to stem the running

stream has signally failed."

It was with this end in view that he

carefully drew out his plans. He published a pamphlet to call attention

to the subject and to get the necessary support "so as to render the

measure he contemplated suitable not for one locality only, but for his

country and the world." Mr Duncan at first met with little response. He

was but too well aware of the difficulties and prejudices he would have

to contend with in dealing with an untried scheme. There were numerous

pessimists ready to quench the impulse and doom it to failure before it

had reached the initial stage, and there was no resident heritor to give

it the light of his countenance ; there were no rich people to come

forward and support it, and there were not many even of the well-to-do

among his parishioners. As for the poor, many of them already belonged

to Friendly Societies, and, as it was, found difficulty in keeping up

their payments. Not the least of his difficulties were' the suspicions

and prejudices of the lower classes where money was concerned. Their

reluctance to trust it to anyone else's keeping is told in the following

words of his own: " Nor were there wanting surmises that the author of

the scheme might himself have some private end to serve in taking

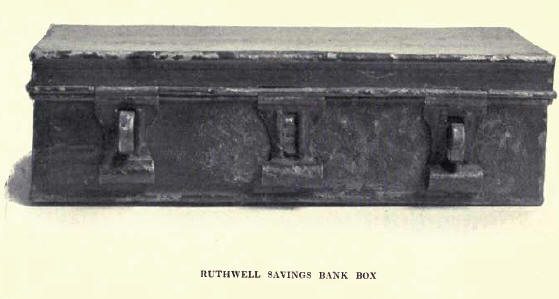

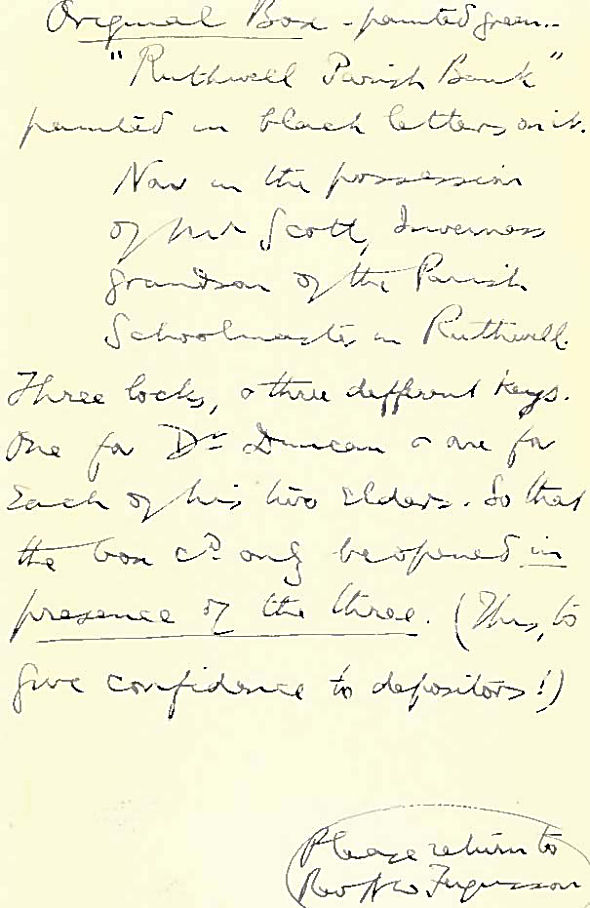

possession of their savings." And this prejudice was overcome by means

of a box provided with three different locks which could only be opened

in the presence of three persons. [Mr Scott, of Inverness, whose

grandfather was schoolmaster at Ruthwell for nearly forty years, has in

his possession the original Savings Bank Box, and has kindly allowed me

to reproduce it. It is painted green, and h»s in black letters on the

lid, "Ruthwell Parish Bank" In his own account of the box he says, "...

if my memory serves me right, my father told me the minister and each

elder had the key of a lock, so that it could not be opened unless the

three were present."] Even under the most favourable auspices an

institution such as he hoped to

found must have endless difficulties to contend with, but he went on and

on, writing, talking, hoping. Though at first somewhat depressed by the

results, by sheer force of work, and his own passionate belief in the

scheme, he pushed it through. To begin with, he had great confidence

that the common-sense of his own parishioners would, in the long run,

prevail, and he felt sure he could in time win them over to see the

necessity of economy and thrift. The foundations of the little bank he

proposed starting must be built on solid rocks; there must be no sandy

foundations to give way and shake the timid confidence of those who

first entrusted their money to its keeping. A stocking, a chink in the

wall, or a loose board in the floor were in those days the only way of

keeping surplus money for the lower classes, as the public banks did not

take less than £10, and the want of a safe place to keep small amounts

often prevented people from attempting to preserve them. Poor people

were in danger of being robbed of their little treasure, dearly

accumulated by much self-sacrifice and denial. The presence of the

tempting nest egg was too often known to others; in that case it was

difficult to avoid lending it, perhaps for a too .trivial reason. The

hearts of the poor are very easily touched by the troubles of others.

The temptation to break into it was more than human nature could

withstand ; they would dive into it, and once that had been done it was

so easy to dive again. But directly the money was safely in the keeping

of the Savings Banks, Mr Duncan knew that they would hesitate to break

into their little store unless for some definite or urgent reason. He

says: "If any method then could be devised for giving to the honest and

successful labourer or artisan a place of security, free of expense, for

that part of his gains which the immediate wants of his family do not

require, with tht power to reclaim all, or part of it, at pleasure, it

would be a most desirable thing even if no interest should be received."

Ruthwell was a very poor parish and seemed a peculiarly unsuitable place

for any experiment of the kind. A trial looked as if it must fail. His

cherished enterprise, however, so carefully worked out with such endless

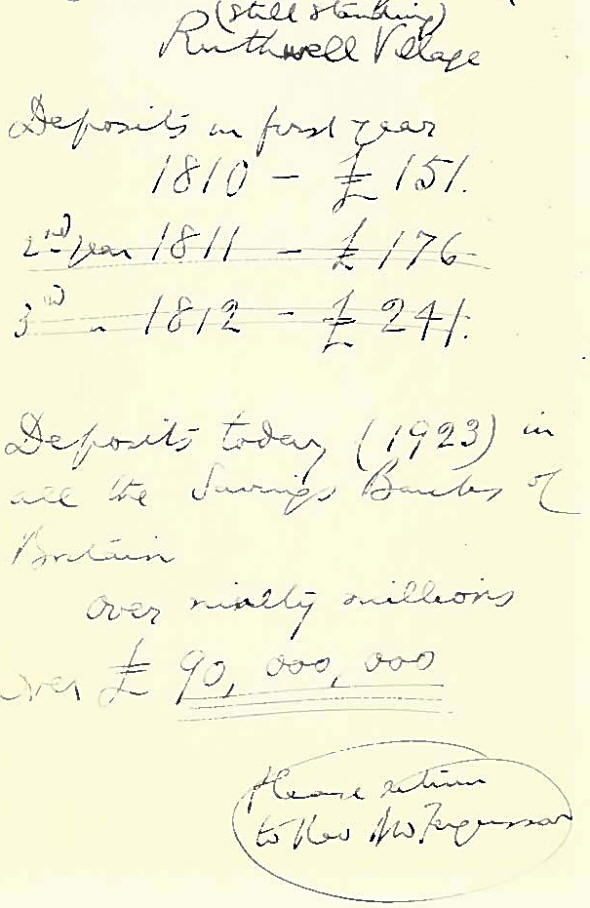

and dogged perseverance, met with extraordinary success. The first year,

1810, the deposits amounted to £151, followed by £176 in the second

year, £241 in the third, and progress now being made by leaps and

bounds, in the fourth year the money deposited was £922. Remarkable

figures and far beyond his most sanguine expectations. Mr Lewin, in his

work on Savings Banks, says : " The fact that an institution of the kind

contemplated could possibly be carried out by a single individual,

however benevolently disposed, is evidence enough of that person's

sagacity and perseverance . . .; " and the Quarterly Review of 1816

says, some years after the founding of the Ruthwell Bank, "Justice leads

us to say that we have seldom heard of a private. individual in a

retired sphere, with numerous avocations and a narrow income, who has

sacrificed so much ease, expense, and time for an object purely

disinterested, as Mr Duncan has done." Mr Duncan carried his point;

Savings Banks were an established fact. His real work began. His

correspondence increased day by day—letters poured in by every post from

town, country, and continent asking for information. The interest taken

in his new scheme was most gratifying, it stimulated him to still

further work. Fortunately for the future success of the new undertaking

he was a remarkable letter-writer, and this laborious occupation never

seemed to tire him. He was always an early riser, and would himself

kindle his fire in the morning and devote himself to long hours of

steady work before the rest of the world was awake. To inspire

confidence in his parishioners he became himself the actuary. They felt

then their money was in his personal keeping. The expenses of stamps,

etc., were borne by him, and his biographer says that " he spent,

notwithstanding the franking privileges of the day, nearly £100 a year

on furthering the cause." Early in 1814 he published his essay on

Savings Banks, which rapidly went into several editions. The following

year an enlarged edition was published. Edinburgh, Kelso, Hawick quickly

followed the Ruth well example, and in the South similar establishments

were founded at Liverpool, Manchester, Exeter, Southampton, Bristol, and

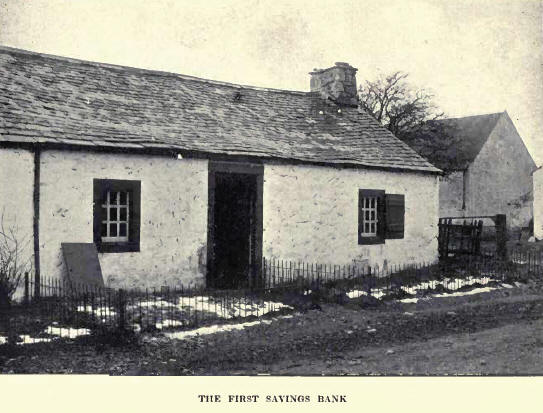

Carlisle. In Ruthwell the small white - washed cottage is still

standing that gave birth to the great movement. It in no way differs

from its fellows, and stands side by side with them in the quiet village

street; but once the threshold is passed you find yourself

in one long

low room with wooden forms around the walls; the door is in the centre

and on either side arc two small windows. Imagine the Httle cottage as I

saw it on a dazzling day in June. The shutters were up and the small

building looked much as if it were taking an afternoon siesta, so lazy

and idle it seemed compared to the other cottages which showed signs of

life, the faint blue of the smoke from the chimneys, the voices of

children and the perfume of flowers. The sun was full upon it, and the

sight of the humble little institution, where the depositors first

brought their hard-earned savings, made one reflect on how small

beginnings may end in great and noble things. For it was here, a hundred

years ago now, that the impetus was first given to what is now a great

movement; it was here in this little wayside cottage that it sprang into

healthy active life, putting out roots and fibres that have since

grafted themselves on to every country in the civilised world.

It was not till some years after the founding of the

parish bank at Ruthwell that Savings Banks were put under Government

protection. They were simply voluntary associations, protected by

private individuals, generally benevolent people of note in their

respective neighbourhoods. The first Act was passed in 1817. Up to that

date the only guarantee that the poor had that their savings were in

safe keeping was the honesty and integrity of the Trustees, and in that

their confidence had never been misplaced. The Ruthwell Bank was, as far

as possible, in the absence of a special Act of Parliament, under the

protection of the Friendly Societies Act, but "the Father of Savings

Banks," as Mr Duncan was frequently called in the House of Commons, was

not satisfied with this state of matters. He took legal advice, from

which it appeared that the protection afforded by the Act was doubtful,

and that a plea founded on its terms might be ruled out as irrelevant if

used in connexion with Savings Bank questions in a court of law. He

therefore wrote to Sir W. R. Douglas, member for the Dumfries Burghs, on

the subject of an Act to deal specially with the matter. He was,

however, anticipated by Mr Rose, so well known as a keen observer and

student of the poor laws, who only a few weeks later introduced the bill

of 1817.

There were clauses in the measure which, for technical

reasons unnecessary to go into here, were found to be quite unsuitable

for Scotland. Mr Duncan, therefore, resisted the extension of the

English Bill to Scotland, and fought an active campaign against it. In a

large measure owing to his attitude the Bill was only passed for England

and Ireland. It was another proof of his sagacity that Mr Douglas, M.P.

for Dumfries, asked Mr Duncan to prepare the draft of a Bill adapted to

Scottish Savings Banks, and to transmit the same to every Savings Bank

in Scotland. Here, again, he was met with opposition, for the Edinburgh

Bank sternly turned its face against the measure and deprecated the idea

of Government interference as injurious to these establishments. So

powerful, indeed, was the influence directed against the Bill that it

seemed problematical whether it would ever have a chance of passing into

law. Opposition, however, only whetted Mr Duncan's enthusiasm. He

managed to get active support from most of the other Scottish Banks, and

Glasgow fortunately supported him. The difference of opinion between the

Edinburgh Bank and Mr Duncan was at its height in 1819. Edinburgh

published a report protesting against State interference ; this was

followed by a very able letter from Mr Duncan to Mr Douglas, M.P., on

the expediency of the Bill, which was published and freely circulated.

The Christian Instructor for March 1819 alludes to the controversy as

follows: "All their objections (meaning the Edinburgh ones) he has

refuted in the most complete and satisfactory manner, and offered such a

full vindication of the measure towards which their hostility has been

so industriously and powerfully directed as must remove every doubt

which that hostility has excited in the public mind. . . ."

But there was also another and far more dangerous

opponent—Cobbett. Cobbett was born in 1762 and was the son of a small

farmer. The first part of his life was spent in agricultural pursuits.

He came up to London in 1783 and entered a lawyer's office, but shortly

afterwards enlisted in the Fifty-fourth Foot. At the dep6t at Chatham,

he had time to educate himself, and he made the most of his time,

rapidly developing a great taste for study. He attained the rank of

sergeant-major, and what was more remarkable still he contrived to save

not less, probably a good deal more, than £150. Yet this son of the

people, the man who had largely educated himself and owed so much of his

future advancement in life to his own thrifty habits, was a bitter

opponent of the State protection of Savings Banks! His celebrated paper,

the Political Register, was the first cheap newspaper. In 1816 Cobbett

had suddenly reduced the price from one shilling and a halfpenny to

twopence. The, effect was instantaneous; the lower classes had now, for

the first time, within their reach a paper conducted by a man of the

people. By this act Cobbett increased the power of the Press threefold,

and the opinions of his paper were received with enthusiasm. In 1817 he

bitterly criticised Mr Rose's Bill, alluding to it as "the Savings Bank

Bubble," and later on as "the most ridiculous project that ever entered

into the mind of man."

But it was in January 1819, in his letter in the same

paper to Mr Jack Harrow on the new cheat, which is now on foot, and

which goes under the name of Savings Bank," that he surpassed himself in

virulence of language. He managed in the most ingenious way to bring

forward his arguments against the scheme. He was a persistent opponent

of the National Debt, which he maintained was a contrivance of the rich

for imposing further burdens on the poor. He speaks of it as "the great

fraud, the cheat of all cheats," and goes on to tell Jack what an

imposture it is, and how shamefully the people have been taxed to pay

the interest upon it. I must quote his own words as they are of great

interest. Speaking of the Borough-mongers as he calls the " Lords,

Baronets, and Esquires," he says that they knew how necessary it was

that a great many rich people should uphold the system. " They,

therefore, passed a law to enable themselves to borrow money of rich

people and, by the same law, they imposed it on the people at large to

pay, for ever, the interest of the money so by them borrowed. The money

thus borrowed they spent in wars, or divided amongst themselves, in one

shape or another. Indeed the money spent in war was pocketed for the far

greater part by themselves. Thus they owed in time immense sums of

money; and, as they continued to pass laws to compel the nation at large

to pay the interest of what they borrowed, spent and pocketed^ they

called, and still call this debt, the debt of the nation; or in the

usual words, the National Debt." He then goes on to argue that Savings

Banks are only a further means, and a particularly crafty one, of still

further feeding the pockets of the detested "Borough-mongers." He

devotes pages to repeating the same refrain, but, to put it into a

nutshell, in a biting paragraph he says : " Now then, in order to enlist

great numbers of labourers on their side, the Borough-mongers have

fallen upon the scheme of coaxing them to put small sums into what they

call banks. These sums they pay large interest upon, and suffer the

parties to take them out whenever they please. By this scheme they think

to bind great numbers to them and their tyranny. They think that great

numbers of labourers and artizans, seeing their little sums increase, as

they will imagine, will begin to conceive the hopes of becoming rich by

such means; and, as these persons are to be told that their money is in

the funds, they will soon imbibe the spirit of fund-holders, and will

not care who suffers, or whether freedom or slavery prevail, so that the

funds be but safe."

"Such is the scheme, and such the

motives. It will fail of this object, though not unworthy the inventive

power of the servile knaves of Edinburgh. . . .[This was not the case,

as the idea originated at Ruth-well, and the Bill of 181!) was brought

forward by Mr Duncan. The Edinburgh Hank opposed it] The parsons appear

to be the main tools in this coaxing scheme." Cobbett succeeded in

bringing over large numbers of people to his views, especially in

Lancashire. A question was asked in the House of Commons whether the

report was true " that the Government was about to seize the funds of

the Friendly Societies and Savings Banks, and apply them to the payment

of the National Debt." This report actually did lead to the breaking up

of some Friendly Societies, causing great loss to those who had claims

on them. The Chancellor of the Exchequer pronounced it to be utterly

groundless," and assured the pubhc that money belonging to the

institutions in question was kept entirely apart .... and even if the

Treasury were base enough, they had not the power to misappropriate

these funds."

The Times newspaper was also hostile to

Savings Banks and kept up this attitude long after the benefits of these

institutions were generally admitted. The more opposition that was shown

the more fully determined " the father" of the measure was that the

matter should be brought to a successful issue. Mr Douglas, M.P., a

great personal friend and a warm supporter of Mr Duncan's policy,

invited him at this juncture to stay with him in London. No doubt this

was with a view to Mr Duncan lending the aid of his powerful personality

to convince any wavering members of Parliament and induce them to

support the Bill they both had so much at heart. A journey in those days

was a great undertaking, and it was his first visit to the great city.

He rode all the way, leaving Ruthwell on Monday morning and arriving at

his destination on Saturday night. He stayed at the Albany in the very

heart of London. The Albany, which was once Lord Melbourne's house, was

altered in 1804 into separate apartments for " bachelors and widowers,"

most of them men of fashion, members of the House of Lords, House of

Commons, or Officers in the Army or Navy. The name of the Albany was

given to these apartments from the second title of the Duke of York.

Many celebrated people had occupied rooms there, including Byron and

Macaulay. There Macaulay wrote a great portion of his History, and it is

recorded in Trevelyan's Life of the celebrated historian that he paid

£90 for his suite of rooms. In an entry in his diary in 1856, he says, "

After fifteen happy years passed in the Albany I am going to leave it

thrice as rich a man as when I entered it." Lord Lytton and Brougham

were also distinguished occupants. No ladies resided there or were even

admitted, except very near relatives, but "this rule," Walford says,

"was not strictly adhered to." Mr Duncan was presented to the Prince

Regent, and no time was lost in getting into touch with various

influential people.

He was himself at the very summit

of life ; his energy was at its full height. He felt able and ready for

all things. Wilberforce promised him his support; Canning was greatly

interested, and asked for his pamphlets; Macaulay showed him great

kindness; Lord Minto became, after reading his views and suggestions, a

convert, though a few days before at a dinner at Lansdowne House he

found him "strangely possessed with the inexpediency of the Bill." The

Lord Advocate supported him. The tide had turned. Of a special meeting

of Scottish members, who had assembled to further discuss the matter, he

writes to tell a friend the result. He says, "I had previously seen and

converted Lord Minto and Lord Binning; I had neutralised Sir John

Marjoribanks and Sir James Montgomery and had Kirkham, Finlay, Lord

Rosslyn, and Mr Gladstone [Afterwards Sir John Gladstone, father of the

famous statesman. He was at that time member for Lancaster.] for my firm

friends." It was surmised that even if it passed through the House of

Commons, the Bill might not be carried in the Upper House, but Lord

Rosslyn promised to give it his special attention and protection, and he

ends by saying, "After a tough and, at one time, a doubtful battle I

have at last carried the day triumphantly." In one of his first letters

to his wife he speaks of London as being " a dreadfully bustling town,

and people pay dearly for their greatness. I would not lead such a life

for all the wealth and honours the wrorld can bestow. . . . O, for my

own fireside with my wife and bairns about me."

He was

destined to remain in London for many weeks. He was asked to give,

before the Committee on the Poor Laws, his views upon these laws, their

effect in Scotland on emigration, etc., etc., and the great problems of

pauperism to which as yet nobody has found the solution. This was the

way he spent his time, feted, and sent for by some of the most

enlightened and interesting men of the day, eager to hear what he

thought, and recognising in him the practical philanthropist that he

was. He would not have been human if he had not felt flattered by so

much attention; he said himself later that "once was quite enough for

the head of a quiet Presbyterian minister," and prayed that he might be

"humbled." He returned in April to Ruthwell, that dear village where his

heart was so closely entwined with the interests of his people. No

offer, though he had many, to remove to a larger or more lucrative

living with wider opportunities had ever tempted him to leave it.

Ruthwell was his home and he loved his parishioners. His return called

forth from his pen these lines, addressed to a neighbouring minister:

"Never poor aeronaut, whose too buoyant vehicle had darted with him

beyond the region of the clouds, and beyond the sight of terrestrial

things, was happier to plant his foot on terra firma than I at this

moment feel in being myself again." Think of the pride it must have been

to him when the Bill that he had fought for so strenuously had passed

into law—through the House of Commons—through the, at one time doubtful,

House of Lords, into the book of the Statutes of the land. Mr Douglas

also wrote to tell him : "You may carry with you the satisfaction of

knowing that the Savings Banks Bill would not have been carried except

by your visit to London." |