It is no small thing to say of Robert Cleland that he is not

unworthy to be named along with two such men as Henry Henderson and John

Bowie. He was one with them in spirit, and he was not behind them in courage

and devotion. All three had been students of Edinburgh University, Cleland

being the last to go forth and the first to be called home. His career was

the shortest of the three, but it was long enough to show how

deeply “Africa” was written on his heart, and it is not unfitting that with

the pioneer missionary who opened the way, and the medical missionary who

soothed the sufferings and healed the sickness of the African people, we

should link the ordained minister of Jesus Christ who went forth there to

teach and to preach the glorious Gospel of the blessed God.

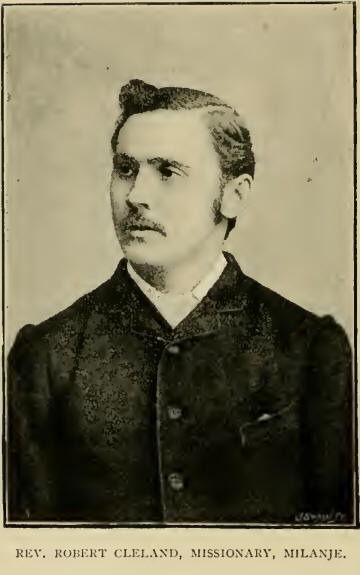

It was neither from the beauties of a rural parish nor from

the culture of city life that God called this servant. He came forth to the

work of God from a humble home amidst the smoke and dust and noise of

Scotland’s “Black Country.” Born in Coatbridge in 1857, he received his

early education first at Dundyvan, and then at Gartsherrie Academy there.

After leaving school, he served his apprenticeship as an engineer in one of

the large engineering works of which there are so many in that neighbourhood.

As a boy he was quiet, painstaking, and in everything very conscientious. I

can remember the foreman under whom he served part of “his time” speaking to

me years ago of the quiet, industrious lad who never seemed to care for

sporting with the other apprentices, but whose mind seemed to be always on

his work, always anxious to understand everything about it. Good man! little

did he know where the lad’s mind really was. That wish to understand

everything, too, doubtless made him the “handy” man he was afterwards, able

to put his hand to anything—to clean a watch or repair an engine or

construct a bridge,—an invaluable gift for such work as lay before him. In

the winter evenings he attended the Gartsherrie science classes, where he

gained certificates of the Science and Art Department for mathematics,

natural philosophy, chemistry, and other branches of science, and this

training and the possession of these certificates also proved helpful to him

in his future career.

It was in his twenty-first year that he finally decided to

give himself to the mission-field. Like Isaiah, he was worshipping in the

House of God when the call came to him. It was in the parish church of

Garturk, on a Sunday in the late autumn of 1878, and the writer, then a

young minister, was making his first missionary appeal to the congregation

over which he had been set only a few months before. Looking round the

congregation, which included a large number of young men, the preacher

asked, “Why should not a congregation like this give not only of its means

but of its men to the mission-field?” Very earnest was the look that then

shone in Cleland’s face. It was as if his very soul was gazing out of those

deep, dark eyes of his. He seemed to hear the voice of God saying, “Whom

shall I send? and who will go for us ?55 and reverently he answered, in his

heart, “Here am I! Send me.” From that hour he was consecrated to God and to

Africa. Much and often did he pray over it, but from that decision he never

swerved or turned back. With characteristic reticence he buried his secret

in his bosom for months. No one heard from him one single word telling of

the new purpose that filled his soul, but all the time he was busy preparing

for the work to which he had devoted himself. He determined to qualify

himself for the position of an Ordained Minister, and his first step was to

begin toiling away quietly by himself at his Latin and Greek. His

fellow-workmen used afterwards to tell how he brought his Greek Grammar with

him to his work, and how, when the dinner-hour came and the others went home

to dinner, he would sit in a corner of the shed eating his “piece” and

getting up his Greek verbs. At length the time came when his secret must

come out, or so much of it, at least. One day he called for me and, to my

surprise, asked if I would examine him in Latin and Greek to see whether I

thought him fit for entering college. As was to be expected, his knowledge

of these subjects was comparatively meagre, but the offer of a little

“coaching” during the week or two that remained ere the opening of the

college session was gratefully accepted, and the progress of these few weeks

showed what a power of work he possessed.

In due time he entered the University of Edinburgh, and

there, in face of difficulties that would have daunted a less determined

spirit, he worked his way through the full seven years of a university

course, helping at the same time to maintain himself by teaching. He worked

very hard, studying late and early. No one knew how much it cost him to make

up all the leeway of those years, and to keep up with class-fellows who had

been taught and drilled in classics at school and then gone straight to

college. In all his classes he acquitted himself creditably, gaining the

approval of his professors and the respect and regard of his

fellow-students. For a short period after his first college session was

ended he went to Lancaster. Here it was that his Science and Art Department

certificates stood him in stead, for it was by the help of these that he

obtained an appointment as a teacher of science in Lancaster Commercial

School. He greatly enjoyed his time there, and in after-years he looked back

gratefully to the experience he had gained while thus engaged, and to the

friendships which he had formed there. In due time he returned to college

and resumed his hard and steady work. During several winters he taught for

some hours every evening the boys residing in the Home of the Edinburgh

Industrial Brigade. It was congenial work, but it was very hard. The big

lads, sometimes rough, though not unkindly, felt the influence of his strong

personality and devotion to them, and they liked him. But it was no light

thing to keep them occupied and busy with their work through a whole winter

evening, and when at ten o’clock he left them and walked wearily home to his

lodgings, he was often much more fit for going to bed than for sitting down,

as he regularly did, to pore over his own studies till the small hours of

the morning. Yet he never flinched, and the thought of giving it up or

turning back never once crossed his mind. In the summer of 1886 he went for

some months to be missionary at Achnacarfly, in Lochaber, under the late Dr.

Archibald Clark of Kilmallie, and kindly recollections of him still linger

among the people there. When visiting in that locality recently, I was

struck with the affectionate way in which some of the people I met still

spoke of him. The tremble in the voice and the eyes that filled as they

spoke told of the strong tie with which there, as everywhere, he seemed to

attach people to him. He was very happy in his work in Lochaber. There was

something about the great hills and the quiet glens that appealed to him,

and he loved tramping about among them—those great long walks he had to take

preaching and visiting his people. It was like a foretaste of his future

work, and left its impression upon him. Twelve months later, when, in his

first letter home, he was describing his approach to Blantyre, he

wrote:—“For miles we were passing through a steep, hilly country, prettily

wooded, so like Clunes Hill in Lochaber that sometimes T could almost

believe that time was a year rolled back.”

All this time he was dreaming of Africa with an enthusiasm

that was almost a passion. Eagerly he read every book that could give him

information about it. But Livingstone was his great ideal. More than one

pilgrimage did he make from his home at Old Monkland over to Blantyre to

visit the birthplace of his hero and see the mills where he had worked as a

boy and the scenes amidst which he had been reared. That a double portion of

that master’s spirit might rest upon him was the constant prayer of his

eager youthful heart. Every step of the great traveller’s journeys through

the Dark Continent he had traced again and again, and every station in the

African mission-field he knew. At that time it seemed as if there was no

prospect of his being sent to Africa by his own Church. The funds at the

disposal of the Foreign Mission Committee, and responsibilities already

resting upon them, greater than they could meet, forbade their increasing

the staff of missionaries in the African field; but he laboured on in his

preparation, assured that God would open a way for him when the time came

that he was ready to go. And so He did. Cleland’s last session at college

was within a few weeks of being ended when an unexpected call came for a

missionary to go to Africa. The Bev. David Clement Scott, head of the

Blantyre Mission, had been home on furlough after five years of work in

Africa, and by his fervid enthusiasm and stirring words had kindled a flame

of sympathy for African Missions in many hearts. One point which he had

repeatedly and strongly urged was the importance of strengthening the

Mission by opening a new station at Mount Milanje, an important centre and

the residence of a powerful chief, about four days’ journey from Blanytre.

The old difficulty, however— want of money—stood in the way, and Air. Scott,

at the close of his furlough, had to sail again for Africa without having

obtained the additional missionary he desired. His words of appeal, however,

remained behind him like seeds taking root in Christian hearts, and long

before he reached Blantyre their fruit began to appear. A few friends in the

congregation of St. George’s Church, Edinburgh, impressed by the necessity

and the opportunity, offered to bear the expense of sending out a missionary

if one could be sent at once.

Shortly after this, there was a gathering of students in the

rooms of the Church, 22 Queen Street, and Dr Scott, minister of St.

George’s, who was present chanced in the most casual way to meet Cleland

among others, and made his acquaintance. It was not long before he

discovered where the lad’s heart was and what was the desire of his life.

Subsequent inquiries abundantly satisfied him that here was just the kind of

man that was needed for Milanje, and for which he and his friends were

looking. The result was, that, after careful consideration by the Foreign

Mission Committee, the appointment was offered to Cleland. Surely no one

called to leave his native land ever received the summons with more eager

joy. He wrote to his mother a characteristic letter, and on getting back her

willing consent,—written with characteristic solemnity and reverence,—he

accepted the appointment. One hardly knows whether to admire more the mother

lovingly yielding her son to God for such work, or the son going forth in

such a spirit. “Of course, I am grateful for the appointment,” he wrote to

the Secretary of the Foreign Mission Committee, “and I trust that a devoted

life may reveal my sincerity of heart better than any mere words can do.” He

was licensed to preach the Gospel by the Presbytery of Edinburgh in April

1887, and on the 29th May following he was ordained a Missionary to Africa

in St. George’s Church, Edinburgh. It was during the sittings of the General

Assembly, and there was a crowded congregation, among whom were many

ministers and others from all parts of the country. To him, with his

shrinking, sensitive nature, it was a terribly trying occasion. “ I would

rather cross Africa,” he wrote to a friend, “ than face the awful ordeal. It

seems a shame to put a poor broken-down mortal through such a public trial,

but I suppose the feelings of the one must be sacrificed that those of the

many may be touched. This seems to be the law of all true life.” Certainly,

as he stood there the centre of the great gathering, so pale and

earnest-looking, and yet so calm and self-possessed, with the gentle light

shining in his dark eye, there was something that drew the sympathies of all

hearts to him, and a link of personal sympathy was forged which made many a

one watch with prayerful interest the steps of his subsequent career. At the

close of the service hundreds thronged round him eager to shake hands with

the young missionary and bid him “ God-speed,” among them being a number of

boys and girls, for each of whom he had a personal word, which no doubt they

would long remember. His mother was prevented by illness from going to

Edinburgh to be present at his ordination, and he had only a few days in

which to go home to Old Monkland and see her before he left. Busy days they

were, full of preparations and hurried farewells to old friends and

companions. Then he paid a flying visit to Leeds on his way south,— to say

“good-bye” to a brother who was there,—and then on to London, all within the

week. Here, too, he had a busy time—so many places to go and so many things

to be got, so many instructions to be attended to, and withal so little time

to think, so little opportunity for the pent-up fountain of feeling to find

outlet. When he went on board thelioslin Casllc he met another young

missionary also on his way to his first work in the African field, Mr. W.

Bell, an engineer, who was going out to Mandala in the service of the

African Lakes Company. At once the two took to each other, and during the

long voyage the companionship and communion of a kindred spirit was very

helpful to both. The vessel sailed from London on the 9th June. I was one of

those who stood and Baw him wave his last farewell as the Roslin

Castle steamed out of the dock, and a bright farewell it was, without one

trace of sorrow or regret. Even in that hour of parting from home and

kindred, a bright joy lit his face at the thought that Africa and his work

there for God were now so near. After watching till the little group of

friends on the pier-head had faded in the distance behind, the two young

missionaries sat down and had a long, earnest talk about the work to which

they were going, and it drew them very close together, that talk. Then

Cleland went below to write, and as the vessel was steaming out of the

Thames he wrote to his most intimate college friend, and this was how his

letter began :—

“Bound for Africa at last!—the land of my hopes, and, I

trust, sooner or later (it may sound strange), the land of my grave! Oh, to

live for it and die for it! and to lie there with all the seeds of your work

growing up around you until we rise to meet Him!

I always like to think of sleeping my long sleep in one of

those vast solitudes—solitudes in which the wail of the slave now rises to

heaven, but which one day will be a garden of God.”

To another friend he wrote at the same time:—

“It is not simply that I am leaving for Africa. That never

gives me a thought—except the thought. Am I worthy for work in Africa? Will

I be able, with the help of a Higher Hand, to do something for Africa? . . .

May He who sustains all and is over all prepare me, soul and body, for the

Master’s use! The great ideal of my life has been to do something for

Africa, even if it should be His will that I only take possession of the

land by a grave. Oh that, in the truest sense, I may be consecrated for such

a work! Africa has been the dream of my past, and God’s leading encourages

me to believe that it will be the joy of my future. It is among my dearest

wishes to be at last laid in its solitudes as a finger-post to point the way

for others. I may fall, but I will as certainly rise again.”

Sadly prophetic words! How we read them now! And how soon

have they been fulfilled! They were not like the ordinary words of a student

writing to his chums. They were a revelation of the man himself, and showed

what manner of man he was and in what spirit he went forth. “Africa” was

written on his heart. To do something for poor suffering Africa was the

dream of his life, and no sacrifice did he think too great, not even life

itself, if he could thereby help in healing “this open sore of the world.”

Surely it was God who implanted that burning desire in his soul! And to

think that already his work for Africa is over, after only three short years

and a half! To-day there is sorrow in the old home, sorrow among the

missionary band at Blantyre, sorrow in the Church ; but Cleland has got his

wish. God gave him his desire. He worked for Africa; he died for Africa; and

now he is sleeping his long sleep in one of those vast solitudes, and the

seeds of his work are growing, and will grow up around him until the day

when he shall rise to meet Rim.

Of his voyage out little need be said. It, too, was like

other voyages. He greatly enjoyed it, and was much benefited in health by

the rest and the sea-breezes. He had a great regard for the captain of the

ship, and spoke most gratefully of much personal kindness which he had

received from him. Changing his steamer at the Cape, he found sailing up the

east coast rather tiresome, and was not sorry when they anchored off

Quilimane. Here the first shadow fell on his path. Tidings met him there of

the death of poor Mrs. M'Illwain, who had died at Vicentis as the Mission

party preceding him went up the river. After two days at Quilimane, he, with

a fellow-traveller as a companion, started at midnight in a small boat for

Vicentis, on the Zambezi, under conditions which reduced the comforts of

travelling to a minimum. “We slept,” he says, “ in a little grass house in

the boat, about three feet high and four feet wide. At our heads were the

bare legs of the native steersman; at our feet (mine reached far out of the

house) were the rowers, singing their musical chant as they pulled together

at the oars.” Three days of this, followed by two and a half days’ march

through the long grass under a burning sun, brought them to Vicentis, the

heat during the latter part of the march being very trying. Writing of it

long after, he said he had never felt it so hot as he had done that day. At

Vicentis he expected to get the African Lakes Company’s steamer up the River

Shire, but on his arrival he learned that the steamer would not arrive for a

week yet. Vicentis is a cheerless and unhealthy spot on the river-bank, and

very reluctantly he waited there. The end of the long week came, but not yet

the steamer. A day or two later came Lieutenant Wissmann, who had just

crossed the continent, taking four years to the task. He had passed through

Blantyre, and gave a glowing account of the place; but he also brought word

that it would probably be a fortnight yet ere the steamer could arrive. Two

or three days longer Cleland waited, and then, as there seemed no prospect

of the steamer, he started in a small boat with a crew of ten men, not one

of whom knew a word of English,—which, he says, not unreasonably, he found

“a great disadvantage!” The slow, weary progress of a passage up the river

in one of these boats has often been described—the high banks, and the mud,

and the rank smell of the decaying vegetation, and the heat, and the

discomforts of the boat, and the irregularity of meals, and the chance

character of the food that one could prepare for himself when the men

stopped to cook their own food. One does not wonder that, in the midst of

these, the fever-tyrant had his hand on him before he reached Blantyre. “On

my fourth day out,” he says, “I had an attack of what I call ‘bilious

fever.’ It lasted a little more than four days, after which, however, I was

able to take to shooting hippos.” Some time later, however, he writes:—“My

health here (at Blantyre) has been quite as good as at home, but they say

that my ‘ bilious attack ’ on the river was fever, and in the circumstances

I dare say I could hardly fail to have been saturated with malaria.”

Eleven days after leaving Vicentis he reached Ivatungas, the

landing-place for Blantyre, from which it is twenty-nine miles distant, and

here he inserts a characteristic parenthesis:—“By the way, Ivatunga is the

Makololo chief, and was one (if Livingstone’s ‘boys.’ Strange that so many

of the river chiefs were Livingstone’s men, who seem to have risen by force

of character to what they are! ”

The march up the road from Ivatungas was speedily

accomplished, and about 9 p.m. in the evening he reached Blantyre, Mr. Scott

and Mr. Duncan having walked out some miles to meet him. Like all who go to

Blantyre, he fell in love with it at first sight.

His expectations of it were high. “Every white man I met

between this and Quilimane,” he wrote, “had said to me, ‘But wait till you

see Blantyre! ’ ”But, high as they were, these expectations were more than

fulfilled, and he wrote home a glowing description of the place, the work,

the people, and, above all, of his own kindly reception among them. “Even

the little black boys and girls,” be said, “came peeping into the room to

see the new minister.”

“I wish you could see Blantyre,” he wrote again; “you cannot

conceive how much good it is doing to Africa. Boys are here trained to all

kinds of work, and many of them are deeply pious. In a few years these will

spread through the land. Even the natives who pass through here daily with

their spears, bows and arrows, and guns are being silently influenced for

good. You cannot expect with a race like these such results as some good

people at home are tired looking for, but one realises here that day by day

a change is being wrought on the whole country round about.”

At once he fell into line and took his place in the work of

the Mission. That gift he had of winning the affection of all who knew him

well soon endeared him to his colleagues, and his stay at Blantyre was a

busy and happy time. But the post for which he was destined was Mount

Milanje, a mountain district about fifty miles from Blantyre, on the very

edge of the Shir6 Highlands. Here Mr. Scott, the head of the Mission, had

long desired to plant a station. It was not only an important native centre,

but it was also a place where the Arabs were in great numbers, and from

which caravans of slaves were continually being sent to the coast. It was,

further, as Cleland said, the hey to Quilimane, as, in the event of the

river being at any time blocked by war, Milanje commanded the direct line of

the overland route to the coast. But Milanje was ruled by a powerful chief,

Chikumbu, who was unfriendly to the Mission. He had an old-standing

grievance as to some runaway slaves of his, Chipetas, having been harboured

at Blantyre years before. The first step, therefore, was to visit Chikumbu

and secure, if possible, friendly relations with him. Accordingly Mr. Scott,

accompanied by Mr. Duncan, set off on a journey to Milanje for this purpose.

Arrived at Chikumbu’s after their fifty miles’ walk, they found that the

chief refused to see them personally. For two days they were kept waiting to

learn his decision as to the reception which should be given them, and one

can understand the anxiety of two such days, waiting on the whim of a

powerful and treacherous chief whose cross mood or fretful temper might at

any time utter the word which would mean their death. But their hope was in

God. After two days, Chikumbu, who still refused to see them, sent his

headmen to demand the immediate return of his slaves. Mr. Scott met this

demand with a counter-proposal that he would redeem the men, purchasing

their freedom at thirty-two yards of calico per head. This proposal was at

once rejected by the headmen with sundry threatenings and war-like

demonstrations, and with a disappointed heart, but grateful to the

Providence that had spared their lives, Mr. Scott and Mr. Duncan returned to

Blantyre.

Baffled thus for a time at Milanje, Cleland went to Chirazulo,—a

place fifteen miles from Blantyre, on the way to Domasi,—and founded a

Mission station there. Here settling among a people who welcomed his coming

among them, he erected with his own hands, aided only by native help, a

building for a church and school and a house for himself, making roads,

building bridges, laying out a garden and fields, as well as establishing a

school and teaching the natives, preaching all the while both by life and

lips the Gospel of Jesus Christ. Here he laboured for nearly three years,—a

true pioneer, with heart and head and hand all disciplined and ready for

whatever God might give him to do. For a great part of that time he was

there alone, with never a white man for a companion. It was a lonely post,

but he loved the African people with a wonderful devotion. “You would love

them too,” he wrote, “if you only knew them.” He saw much of the horrors of

the slave-trade, and often his heart bled for the wrongs and sufferings

which he saw inflicted. More than once with his own money he redeemed the

slave, and with his own hand sawed the slave-stick from the neck and set the

captive free. Again and again, in his loneliness, he was down with the

terrible fever, but ever as he recovered he was at work again. One of his

letters.written from Cliirazulo on the 27th October 1S88, gives some idea of

the heart-pressure under which that work was carried on by the lonely

missionary:—

“Work here,” he says, “continues as usual. We cannot boast,

but I do pray that some seed may fall on good ground; and I know it will.

Yesterday we went to the hill in the morning as usual. Just fancy yourself

in Africa on a mountain side. The sun is shining brightly on the native

village, with its beehivelike grass huts. Here and there under huge trees

are gathered groups of people. On a rock near, women are pounding maize, men

are weaving mats, and the children are happy at play. A little way apart

from one of these groups, and alone, we see a slave sitting painfully under

the weight of a heavy slave-stick. His eyes are dreamily following us. We

speak to a group of women, and they ask us when rain will come. £ Father,’

they say, ‘pray for rain, or there will be hunger.’ After conversing with

groups here and there, and asking them to come to the 1 talk about God,’ we

get all gathered under one village tree. Just as the service is beginning we

hear far away up on the hillside a woman calling with that peculiar strained

voice—strained to suit the distance. All is silence. Then we hear again, and

this time we distinguish plainly the word ngondo, and soon several of the

men rush up. It is news of war. Some boys from the other side of the hill

have been captured at Lake Shirwa when fishing with their fathers. All is

excitement, and we hear them say, ‘They will be taken to the Matapwiri,’—a

great Arab centre on Milanje, whence they will be driven to the coast, sold,

and perhaps shipped off who knows where? In a little some one suggests, ‘Let

us be quiet until the white man speaks about God, and then we will hear

about the war.’”.Writing at another time he says :—“At the service in church

here we had about a hundred people present, but no children. The mothers, I

heard, were afraid, and kept them at home. One of those present was a slave

whose future was very uncertain. A more touching scene could not be depicted

than when he stood alone outside our little church, with no one to take up

the burden of his heavy yoke, and so help him on; or as he sat on the ground

behind the rest, so wretched-looking, painfully twisting his neck in the

slave-stick to look up or around him. But what is this case, heartrending

though it be, to that of the thousands who are herded down that dreadful way

to the coast at Shirwa? I found I was on a great slave-route, and saw a

caravan said to be with ivory. ‘ Yes,’ said one of my boys, ‘but black

ivory!’ . . . That poor slave I spoke of has begged me to buy him. ‘I may be

sold to the coast soon,’ he said. ‘Buy me, and I will do your work.’ His

poor heart is breaking, but his is only one in a multitude of breaking

hearts in this dark land. I shall never forget how one day a poor woman

rushed into the station and cried for me—for the white man—to save her.

‘They are taking me to the coast to sell me,’ she said.

'Oh, save me! They have stolen me from my home with the

Chikumbu tribe over the river.’ I often wonder where she is now. Perhaps her

heart broke altogether on that dark way to the coast, or is breaking now,

somewhere far away, for her old home over the river. People at home cannot,

I think, feel as we feel when we stand face to face—ay, and often

helpless—before such scenes. But with life before us hope runs high, and we

thank God in our loneliness for the great blessedness of being able to do

our weak little best to bind up the broken-hearted, to proclaim liberty to

the captives and the great brotherhood of men. Oh, come over and help us! ”

With that strange, deep love of Africa filling his soul,

everything about its poor degraded suffering life seemed to go to his very

heart. In another letter he wrote:—“How touching it was to hear, through the

grass walls of the hut where I slept, a woman wailing for hours for her

husband, who had long been dead! She had dreamed of him in the night, and

(as is the custom) she came out and paced before her hut through the silent

hours of the morning, calling him to come back to her in strangely pathetic

and yet weirdly musical words, pausing at times to speak to the dead in her

natural voice.” But, indeed, never a letter came from him in which he did

not sigh over the cruel wrongs of his adopted people; and how his

indignation flashed when he thought of self-satisfied Christians in the

Church at home supinely indifferent to these things, callous to such

sufferings, and deaf to every appeal on their behalf! He could not

understand such people.

In the autumn of 1888 the Rev. Alexander Hetherwick,

missionary at Domasi, a station fifty-five miles north-east of Blantyre,

came home on a much-needed and well - earned furlough, and during the

sixteen months he was absent Cleland took charge of the work at Domasi,

along with his own work at Ckirazulo, walking regularly the long distance

between the two places. There he had the companionship of Mr. R. S. Hynde,

teacher of the Mission school. The companionship of such a one was a great

joy to him, and a fast friendship was formed between the two. It was no mere

formal supervision of the work that he took while at Domasi. It was like

everything he did, thorough and laborious. Nor was it confined to preaching

and teaching. He was as ready with the spade and the hammer and the axe as

he was with the Yao lesson-book or the New Testament. At the time of Mr.

Hetherwick’s return we read in the Blantyre Supplement—the little magazine

printed at the Mission printing-press:—

“Mr. Cleland has done Roman work here during the sixteen

months of Mr. Hetherwick’s absence. A footpath eight miles in length has

been hoed along the base of Mount Zomba from Mr. Buchanan’s plantations to

the station at Domasi, and has facilitated immensely communication between

the two places.

Mr. Buchanan cleared part of it at his end as far as the

boundary of his property on the Naisi. A good road has been made from the

station to the chiefs village, crossing the Domasi River by a bridge which

is a triumph of engineering skill. A water-channel fully a mile long brings

the water of the Chifunde stream close to the station—a great boon. Thus we

have good roads and good water,—two potent civilizers of a new country.”

Then he returned to Chirazulo and continued the work there,

not without encouraging tokens of blessing. To help him in it he had with

him Kapito and his wife, Rondau,—natives who had been in the Mission at

Blantyre ever since its commencement. They had been baptized a few years

before, and on Easter Sunday 1887 they had sat down together at the Table of

Holy Communion, the first communicants of the native Christian Church. Now

they are helping to train their countrymen in the knowledge and love of

Christ, and faithfully and happily Cleland and they lived and worked

together. From time to time he paid short visits to Blantyre, where he was

always a welcome visitor, and occasionally he preached in the church there.

This was always a trial to him, for he was terribly diffident of his own

powers; but some of those who were accustomed to hear him, speak of his

remarkable power in the pulpit, of his singularly clear perception of the

truth, and of the spiritual power with which he preached.

But Milanje was his destination, and he never lost sight of

that goal. All this time he was looking across to the mountain as the place

where he was yet to be, and repeated journeys thither had been undertaken in

hope of finding the door open for starting the Mission there. After the

visit of Mr. Scott aud Mr. Duncan, already referred to, and while th.ey were

returning to Blantyre disappointed at Chikumbu’s refusal to make terms of

friendship, the chief changed his mind, or perhaps he took a different view

of the situation from his headmen. Perhaps it occurred to him to ask himself

whether all those yards of calico should be lost, or whether it might not be

dangerous to offend “ the white man.” However it might be, he sent his son

to Blantyre with a diplomatically polite message. He was sorry that, having

been away on a hunting expedition, he had not seen Mr. Scott (!), but he

hoped he would soon return to visit him, when he was sure some amicable

terms could be arranged. Some time after, Mr. Scott paid a second visit,

accompanied by Dr. Bowie, and saw the formidable chief in his native

village, when they were able to settle the matter of the slaves and their

redemption, and to establish friendly relations between him and the

missionaries. A formal document was prepared, and duly signed by the various

parties to the agreement. It is something of a curiosity in its way. It is

as follows:— '

“Blantyre, Quilimane, East Africa,

26th May 1858.

“By these presents be it known that I, the headman of

Chikumbu, have received on Chikumbu’s behoof, to carry to Chikumbu from Mr.

Scott, head of the Blantyre Mission, on behoof of said Mission, two trusses

of cloth, and that this is the earnest to Chikumbu himself of three more

trusses yet to follow* to be divided amongst Chikumbu’s headmen as Chikumbu

himself shall see fit, and that these five trusses shall be for settlement

of all past mlandu concerning slaves and all else, and the establishment of

friendly relations between the English and the said chief, Chikumbu.

“In witness of which first part of transmission to said

Chikumbu, we, the undersigned, append our signatures.

(Signed) John Bowie.

David Clement Scott.

Masonga (his mark).

D. C. S., Witness.

Chendombo (his mark).

D. 0. S.”

“Blantyre, 4th June 1888.

“Be it further known that three trusses of calico are this

day handed over to Chikumbu’s headman, Masonga, and headman Kanjole with

him, on behoof of Chief Chikumbu; and that Chikumbu through them now

declares that these five trusses (viz., the two formerly sent and these

present three) finish the mlandu; that there is no further ground of quarrel

between the Chief Chikumbu and the English on account of slaves which

formerly ran away, or on account of any one of the slaves; and that

friendship is herewith established and secured.

“In witness whereof, we, the undersigned, set to and append

our names.

(Signed) David Clement Scott.

Masonga (his mark).

Kanjole (his mark).

John Bowie.

Douglas R. Pelly. Henry Henderson.

"Signed this fourth day of June, eighteen hundred and

eighty-eight years, at Blantyre Mission Station, Shire Hills, East Africa.”

Such were the title-deeds to Milanje. They opened its closed

door, and the chief now expressed his desire that the missionaries would

come and live in his territory. How gladly would Cleland have gone! But by

that time it was impossible, for Hetherwick was away home, and he had Domasi

on his hands as well as Chirazulo. There were other difficulties in the way,

too. Chikumbu himself was fickle and uncertain, although when, at

Christmas-time (1888), Cleland paid a visit to the mountain, he still

desired him to come and live there. Portuguese troubles, too, were now

hanging over the Mission, hindering everything and increasing the

difficulties and uncertainty and it was not till May 1890 that Cleland was

able to go to Milanje definitely to settle. Chikumbu received him with every

token of friendship, aud both the Wayao and their neighbours, the Wanyasa,

under Chipoka, welcomed him; but it was not long before it became evident

that Chikumbu’s friendship was not to be depended on. Cleland’s tent was

pitched under the great trees on the side of the mountain, and he desired to

purchase land on which to erect a house. So many difficulties and troubles

however, were raised regarding the land, that Cleland’s carriers, who had

brought his things, began to suspect the chief of seeking a quarrel which

might furnish an excuse for seizing the goods, and it was with difficulty

that they were prevented from running away in the night. Several days full

of anxiety and trouble were thus spent, when, to make matters worse, Cleland

was laid down with fever. After a few miserable days he was sufficiently

recovered to go off, leaving tent and everything, and make a hurried journey

to Blantyre. Here he got quit of his fever, and after a few days more, was

able to return to Milanje, Mr. M‘Ilwain, the joiner, accompanyiug him. Soon

things seemed satisfactorily settled, and Mr. M‘Ilwain was able to return to

Blantyre, leaving Cleland to the work of clearing the ground and preparing

the sun-dried bricks for the erection of a schoolhouse and of establishing

the Mission by opening a school for the Wayao children.

And so he was on Mount Milanje at last! Oh, the joy it was to

him to be there ! I wish I could let you see the eager, happy missionary at

his work,—his little tent under the great trees, and himself and his

co-workers busy as could be, making bricks, digging foundations, teaching

the children. In the September number of the Blantyre Supplement he

wrote:—“After more than ten years of effort the Mission has at last secured

a footing on Mount Milanje!” The goal of his hopes was reached. The standard

of the Cross was planted on those heights which he had been sent out to

claim, and his heart rejoiced.

For a time things went smoothly, but his difficulties were

not yet over. They were in reality only beginning. The two tribes which were

to unite in peace around the missionaries of the Prince of Peace were still

savages, and they could not easily throw aside their wild nature. Chikumbu,

who had been for years the scourge and terror of his district, was still

eager to have the Wanyasa people under his rule, and treachery and cruelty,

war and bloodshed, soon broke out around the young Mission. One day Chikumbu

made a sudden and fierce attack on the weaker tribe, the chief himself at

the head of his warriors wildly waving an Arab flag inscribed with verses

from the Koran, and urging on the slaughter and destruction. Cleland, who

was at the time suffering from fever, hurried to the scene, and heedless of

risk or danger, made his way through the fight to the chief, and quietly but

firmly taking the llag from his hand, ordered him to desist. Strangely

impressed, the chief submitted, and yielded up his llag, saying, “Lalal

(Cleland) has a brave heart, like Chikumbu himself.” For a time the fighting

was over, but the feud was deep-seated and chronic, and Chikumbu was

grasping and treacherous, and again and again trouble and difficulty arose.

At one time Cleland thought of removing to some more peaceful part of the

mountain, but to do that was to leave the Wauyasa to the tender mercies of

Chikumbu, so he held on at his trying post. His faith failed not, and his

work went on. “Our small school, since started,” he wrote, “will, we trust,

not be hindered by future hostilities, and we hope that the difficulties of

these last three months may be but the birth-throes of a future day of

peace, when the healing beams of the Sun of Righteousness will kindle the

love of man to man in the dear love of God.”

Early in September he went to Blantyre to attend a meeting of

the Missionary Council, when his friends wrote that, in spite of the

troubles he had gone through, he was looking much better than when he was

there before. He was so bright and happy, and seemed altogether in such good

spirits, though his troubles were by no means over, and it was settled that

Dr. W. A. Scott should accompany him on his return, to support him iu any

further difficulties with Chikumbu. Sunday the 14th September was Communion

Sunday at Blantyre. In the morning they all sat together at the Table of the

Lord, and in the evening Cleland preached and closed the Communion service.

Very beautiful,—almost like a vision,—is the glimpse we get of the little

church that day, and the little company of disciples, for so many of whom it

was the last Communion on earth. I love to think of Cleland closing that

memorable service, so far away from the Coatbridge smoke,—so far from the

green hills of Lochaber,—in the heart of suffering Africa, which he loved so

passionately, yet in the bosom of the Christian church planted there through

Christian sacrifice,—in that fellowship of the saints which was so sweet to

him, and in the very holy of holies of the Christian temple, standing

himself with uplifted hands speaking words of benediction on the Church of

God. It was from such a time of Holy Communion that he went out again into

the night, as his Master went to the garden and the Cross.

There is not much more to tell—only the end. Dr. W. Scott and

he returned to Milanje, but the difficulties with Chikumbu increased to such

an extent that they were relunctantly obliged to leave him, for a season at

least. They made a journey down the Ruo, and then returned to a place at the

Linge, between Chikumbu’s and Nkanda’s. After spending a few days with a

headman, Chakamonde, they went into a little round native hut near the place

they had chosen for their new quarters. There they remained for a week,

during which time Cleland went across to Chikumbu’s and had “the stuff”

brought over. Then they set to work to prepare a new station, Dr. Scott

digging pits for the poles of the schoolhouse, and Cleland working at a bit

of a road to the stream. That afternoon (Tuesday) Cleland took ill—very ill.

Both of them had been having touches of fever, off and on, for some time;

but this was much more serious. What a blessing it was and how thankful we

are now that his companion at the time was the doctor! Everything was done

that could be, but there was no improvement. He grew worse. On Thursday

messengers were despatched to Blantyre for more medicines and port wine, and

the doctor had him moved a great way up the hill, near the rocks. By this

time he was completely prostrate. It was a terrible place for wind up there

near the hilltop, so Dr. Scott had a little house built, nine feet by

twelve, high in the centre, and strong, with a grass roof, and “tolerably

cosy.” All Friday and Saturday he lay there, every symptom growing

alarmingly worse, till the doctor had almost lost hope. He was dull and

apathetic and not like himself, “which,” says Dr. Scott, “made one feel it

was a patient he was attending, and not poor Cleland, which was somewhat

easier to do.” On Saturday the messengers returned from Blantyre, bringing

a machilah to convey him thither. He was himself anxious to go, so next

morning men were got for carriers,—fortunately without much difficulty—and

the party set out for Blantyre as fast as it was possible to go. That night

they stopped to rest at a place called Medima, a weird, dreary place. Dr.

Scott, writing of it, says:— “I would rather have gone on to Chintzorbedzi,

for Medima is a doleful place. It is the place where that Japanese died; and

there is another grave, too; and lions infest the place. Cleland, however,

wished to stop there, and we did so. It was a strange, strange night. At

midnight he was so ill I scarce thought he could live through it, and I said

to myself, 'If not tonight, it will be to-morrow night.’ The hiccough was

constant now, rhythmical, every third inspiration; and what a sound it made

there—without another in all the lonely forest except now and again a

leopard grunting round the camp.” After resting till 2.40 a.m. the caravan

started again. It was pitch-dark, and they had to pick their way through the

bush by the light of the candle-lantern which Dr. Scott carried, who, poor

man ! worn with fatigue and watching, was sleeping on his feet as he walked,

and from time to time stumbled into the bush as the path took a sharp or

sudden turn. A dreary sunrise saw them eagerly pushing on, and at 10.30 the

sad procession filed into Blantyre, twenty-four hours and a half from the

time they had left the mountain.

Arrived there, remedies were applied and everything that love

and skill and care could do for him was done. The sight of friends around

him, and especially of bis beloved Dr. Bowie, acted like a tonic. He

brightened up on seeing them. “ It does me good to see you,” he said to Dr.

Bowie; and he really seemed to improve. Alas ! it was the flickering before

the darkness. Dr. Bowie and Mr. Scott arranged to divide the night between

them to watch by him by turns, but in the first watch of the night, about

ten o’clock, while Mr. Scott was with him, without a word, without a

struggle, he passed away. His warfare accomplished, his toils over, another

“ Livingstone Man” had died for the redemption of Africa. As they looked on

him there, so peacefully at rest after all his labours, a feeling almost of

envy was in every heart,—cc Blessed are the dead which die in the Lord from

henceforth: Yea, saith the Spirit, that they may rest ' from their labours

; .and their works do follow them."

This was the ioth of November. Next day they laid him in the

little cemetery at Blantyre, natives and Europeans sorrowing together around

his grave. Thus Cleland of Milanje sleeps his long sleep, as he prayed that

he might, in one of the vast solitudes, and already the fruits of his work

are growing up around him. Already those vast solitudes are becoming the

garden of God.

“Now the labourer’s task is o’er,

Now the battle-day is past,

Now upon the farther shore

Lands the voyager at last.

Father, in Thy gracious keeping

Leave we now

Thy servant sleeping.”

Very deep was the impression made at home by the news of the

young missionary’s death,—and especially among those who, like himself, were

still young men. He had been one of the earliest members of the Church of

Scotland Young Men’s Guild—a Union embracing a large proportion of the young

men of the Church. He had been the first to go from its ranks to the

mission-field; and he was the first of tbeir number to be laid in a

missionary’s grave. We do not wonder, therefore, that when the Guild first

met in its Annual Conference after his death, the Delegates present,

representing their brethren in all parts of the land, resolved to erect in

the new church at Blantyre a Memorial Tablet recording their affectionate

remembrance of him and his work. And so, beside the tablet that there

commemorates Henry Henderson, and the windows that speak of Dr. Bowie, there

is to be seen a simple brass tablet bearing the following inscription:—

The Rev. ROBERT CLELAND,

Born at Coatbridge, Scotland, September 4, 1857.

Ordained a Missionary to Africa, May 29, 1887.

Died at Blantyre, November 10, 1890.

This Tablet is erected

by

The Members of the Church of Scotland Young Men’s Guild, in Memory of

the First of their Number laid in a Missionary’s Grave.

“Till He Come.” |