HERALDRY was employed in the feudal ages to display

the exploits of chivalry, and to reward as well as commemorate its

triumphs over oppression and violence. Amidst the imperfections of

uncultivated eloquence and a general ignorance of written language, the

ensigns of heraldry were peculiarly significant. They addressed the

imagination by a more direct channel and in a more striking manner than

words; while at one glance they recalled the most important events in

the history of persons, families, and nations. Their immediate relations

to war, and to the honourable distinctions arising from it, connected

them with the deeds and manners of former times. Exhibited on the

shields and vestments of warriors, they also adorned the most splendid

apparel of peace; and were often transferred to more durable materials,

to perpetuate the memory of those who bore them. They formed the chief

ornaments in the palaces of the great, were chosen by artists of various

professions to embellish their respective works, were set up in courts

of judicature, and impressed on the public money. Thus, to the utmost

extent of their application, did armorial bearings become the symbolical

language of Europe.

In all the countries of Europe, rank, title, and

precedence are the grand prizes in the race of life. This is especially

true of Great Britain, where, from many causes, these honours are

universally and justly believed to be endowed with a "mortal

immortality," to be stable as the rocks that gird our isle; but that the

avenues to the titled platform, until a recent period of our history,

have been too jealously guarded, and that the honours due to genius,

valour, patriotism, and industry have been too much bestowed in the

spirit of party, will hardly be denied.

The nobles of a land should constitute at once its

glory and its strength; they should be in some respects its "turrets and

foundationstone." In no country are these requirements so generally met

as in our own, where diadems and coronets cannot shelter from the

consequences of dishonour, but, on the contrary, derive additional

lustre from the practice of virtue and the efforts of patriotism.

A Crest is the uppermost part of an Armoury, or that

part of the casque, or helmet, next to the mantle. It derives its name

from Crista, a cock's comb, as it was supposed to have been originally a

projection over the top of some helmets (many of which, however, had

none), and it has been supposed by Antiquarians that the first hint of

the Crest arose from this projection. The Crest was deemed a greater

mark of Nobility than the Armoury, as it was borne at tournaments, to

which none were admitted until they had given strong proofs of their

magnanimity. Hence, the word Crest is figuratively used for spirit or

courage. The original purpose of a Crest, as some Authors affirm, was to

make a commander known to his men in battle; or, if it represented a

monster, or other tremendous object, to render him warlike and terrific.

But there is no satisfactory proof whether the Crest was really meant to

render a leader easily recognised by his men, to make him look more

formidable in battle, or as an ornamental mark of distinction.

Some Writers imagine that Crests were originally

plumes of feathers; but, in all probability, these were nothing more

than a particular kind of Crest. The earliest Crests with which we are

acquainted, were animals of different kinds, and their parts, monsters,

branches of trees, plumes of hair or feathers, and the like.

The Crest was an honourable emblem of distinction,

which frequently characterised the bearer as much as his arms, and was

sometimes constituted by Royal Grant. Crests are said to have been of

particular use in tilts and joustings, where no shield was borne, for

the bearer was thus distinguished who would otherwise have been known by

his armorial bearings. We find in the representations of ancient

encounters, that the combatants appear with enormous Crests, almost as

large as the helmets.

Those Knights and Gentlemen, who repaired to

tournaments, were distinguished by their Crests. None were deemed .

worthy of partaking of such fetes who did not bear arms of some kind,

unless of undoubted superiority by birth or merit. Crests were likewise

embroidered on the vestments of the attendants at the processions of

Parliament, Coronations, and public solemnities; they were also engraven,

carved, or printed on property in the same manner as coats of arms.

According to the general opinion, the Crest was not hereditable like the

arms of a family, and, consequently, every successor might assume a new

one. This, however, was not the practice of this kingdom; for it is well

known that the Crest of many families, being esteemed as distinctive as

the bearings in the shield, has been transmitted from one generation to

another for several centuries. The immense variety of Crests has

probably arisen from the younger branches of a family retaining the

paternal coat, and assuming a different Crest ; and this may be the

cause for supposing that the Crest may be changed though the arms may

not. Some declare a Crest is a mere ornament, but it has been so much

considered a mark of distinction that different Sovereigns have made

additions to the Crests of their subjects. Indeed, it was uniformly

esteemed an honourable symbol. In addition to Crests being the subject

of Royal Grant, there are instances of some having been assumed and

confirmed in commemoration of warlike deeds or other honourable events.

Some were taken to preserve the fame of a progenitor, whose name implied

something martial or illustrious, and others were allusive to dignified

offices. Several have been granted for certain services. It appears from

ancient monuments, that the Crest consisted of some plain and simple

device, or what was. applicable to the assumer only; as appears from an

eagle's head, a bird's wing, a peacock's tail, a banner, &c. But so

great has been the deviation from this practice, that it is impossible

to assign any rule for the subsequent assumption of Crests. Many persons

of different names bear similar Crests, and as many of the same name

bear different ones. Every day we may behold the most uncommon,

complicated, and unintelligible Crests, chosen without design or reason.

Women, it is generally asserted, may not bear Crests, because in ancient

times they could not wear a helmet. We have, however, innumerable

instances of women bearing coats armorial ; a fact particularly

illustrated by their seals, which are still preserved : and here,

undoubtedly, is a gross inconsistency, for a woman was as incapable of

using a shield as of bearing a helmet.

The period when Crests were first introduced into

Britain cannot be ascertained. We find in a drawing of the thirteenth

century, relative to a military encounter of Ofia, there is a figure

with a kind of Crest on the helmet; and the same figure occurs again in

another transaction of that time. The great seal of Richard L, who died

A.D. 1199, first represents the English King with something on his

helmet resembling a plume of feathers. After this reign most of the

English Kings had crowns on their helmets. On that of Richard II., prior

to the year 1377, is a lion on a cap of state. On the helmet of Henry

IV. is his Crest, as also on the head of his horse.

Alexander III., who began to reign I 249, is the

first of the Scottish Kings who appears with a Crest: he has a flat

helmet with a square grated visor, and a Crest consisting of a plume of

feathers; a plume is likewise on the head of the horse. The helmet of

Robert I., who began to reign 1306, is found with a triangular grated

visor, a crown above it, and plumes on the horse's head. Ornaments are

on the head of Edward Baliol's horse, nearly of the same period. The

visor of David, the successor of Robert, is in front, but no Crest on

the helmet, nor have the two succeeding Kings any. James I., in the

beginning of the fifteenth century, has a lion on his helmet for a

Crest.

At the time the Royal Seal exhibited no Crest they

were common on those of subjects. It is affirmed that, before the year

1286, the Crest, accompanied by the mantlings and wreath, was known in

England. In 1292 there is a seal of Hugh le Despencer, with a warlike

figure on the helmet and horse's head. These figures are frequently to

be met with in the thirteenth century, but what they represented, or

what their utility was, is doubtful. There is a dragon on the helmet of

Thomas Earl of Lancaster, who was beheaded A.D. 1322. On the reverse is

a swan above the shield, just where a Crest should be, on the one, and

on the other a lion ; but whether they were designed for Crests, or for

figures on which the shield was hung, as was then usual, cannot be

positively said, for it was sometimes suspended from an eagle's back

around the neck, or hung on a tree.

The same may be said of Scottish Crests; though none

are on the great seal they are frequent on those of subjects. There is a

writing of great importance, dated 1371, to which many seals are

affixed, and most of them have a Crest. On a seal of the Earl of

Strathern, attached to a writing, 1320, is a shield placed between

eagles, so that the head of the bird appears above, like a Crest. The

helmet of Robert, Governor of Scotland, bears a lion, 1413; and the same

is on that of Murdac, his successor, both being Crests.

The chief sources from which Heraldic instruction is

to be derived are the seals which are appendages to ancient writings,

illuminated manuscripts, tombs, and buildings. Seals are the most

authentic, but proper illuminations probably afforded better

illustrations, because seals bear the armour only in a particular

character. It is also very probable that the same seal hath served for

several generations. Indeed, one of the most useful purposes to which

both Crests and armorial shields were applied, was in the seals affixed

to written instruments, as already intimated.

To a volume like the present, further preliminary

observations would be superfluous; we shall therefore close this brief

introduction with informing the reader that the objects of this work are

to encourage the study of this important branch of the Heraldic science;

to present as full a collection of Crests as the limits of the work will

admit; and to exhibit a large number of subjects, which for drawing and

engraving have never been equalled, and which will serve as a standard

of excellence for all future time.

29 ALWYNE ROAD,

LONDON, September 1883.

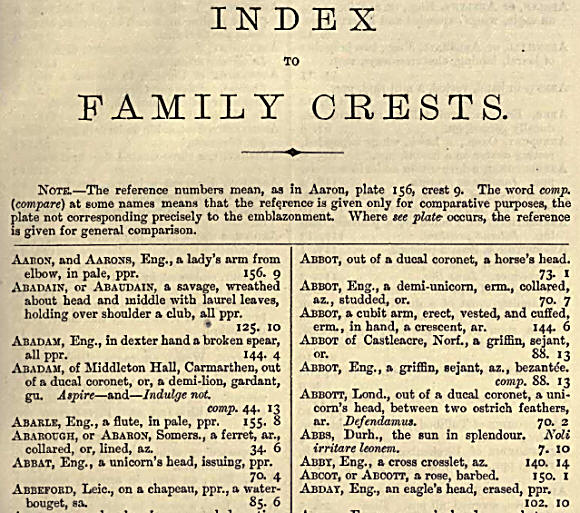

This is an example page to show you the format used