|

THE

PLANTS OF THE GRASSY PASTURES

The

grassy pastures are composed for the larger part of certain grasses such

as the Sheep’s Fescue (Festuca ovina) and the Matgrass (Nardus

stricta). Besides these grasses man y species of sedges and rushes

occur especially in damper areas. Naturally, heather and crow-berry cover

large areas of the mountain slopes, but where they occur we have typical

moorland vegetation and hence I shall deal with these species in the

chapter entitled ’Moorlands’.

Several

species of flowering plants are also found n the grassy pastures. They

have to contend with difficult problems of seed distribution due to the

fact that the grasses tend to colonize vast areas to the exclusion of the

other species. We shall find that plants living in the grassy pastures

are perennial and, by means of climbing or tall stems, overtop the grasses

in order to display their flowers well above the grassy screen.

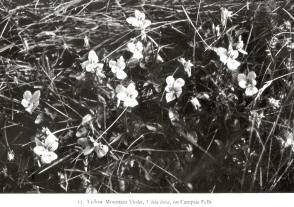

Yellow Mountain Violet (Viola lutea) Yellow Mountain Violet (Viola lutea)

One of

the most beautiful plants to be found in the grassy mountain pastures of

the western Highlands is the Yellow Mountain Violet. It is one of the

loveliest species and is a very interesting plant.

It

possess a short, underground stem in which food reserves are stored. This

stem branches and hence can give rise to several plants, leaves and

flowers being produced from buds at the tip of each branch. In order to

colonize as much land as possible, the rhizome gives rise to long,

creeping stems called runners; these pass between the stems of the grasses

and other plants and so reach favourable places at considerable distances

from the parent plant. It then sends out roots into the soil from its

nodes. Once these have penetrated the soil, leaves are produced and

eventually flowers. In time the portion of the runner connecting this

daughter plant to the parent dies and so an independent plant is formed.

This in time sends out runners and so eventually large areas are

colonized.

As a

further aid to invasion of new territory, the fruit of the violet have a

special mechanism by which the seeds are forcibly expelled to a

considerable distance. It will thus be realized that this plant is very

well equipped for the life struggle. To this must be added the beautiful,

highly specialized flower which are constructed for cross-pollination by

bees.

The lower

petal of the flower is much large than the others and acts as a landing

stage for the bee; it is also prolonged backwards as a spur in which the

nectaries are concealed. The spur can only be approached through a very

narrow passage between the stamens and the base of the petal. As if this

were not enough to deter unwelcome visitors, the bases of the petal are

hairy to further obstruct the entrance. Around the pistil are five

stamens which have short filaments and whose anthers are applied closely

to the top of the ovary below the stigma. They open inwards and their

pollen is drier than n most insect-pollinated flowers. The stigma is a

knob-like projection on the summit of the ovary, with a tiny flap

projecting downwards from the lower side. From the two lower stamens two

white nectarines project back into the spur.

When a

bee visit’s the flower it alights upon the lower petal and, guided by its

dark begins, pushes it had into the entrance of the flowers. On so doing,

any pollen on its head will adhere to the stigma which obstructs its way.

Its head will only go a short distance beyond the stigma, but then it is

below the anthers and as it pushes its tongue down to the nectaries, it

disturbs the stamens causing the dry pollen to rain down on its head.

There is

no danger of this pollen being left on the stigma as the bee withdraws its

head, because the tiny flap at the base of the stigma is forced up over it

and prevents any pollen touching it.

Through

this marvelous mechanism, the violet assures cross-pollination and makes

sure that its nectar will only be accessible to its particular benefactor.

The

violet also produces tiny green flowers, which never open. They contain

stamens and a pistil and are self-fertilized. These flowers are know as

cleistogamous flowers and are fairly common in the plant world, occurring

in the White Dead Nettle, the Balsam and Wood Sorrel in addition to the

Violet Family.

The

advantage to the plant of these flowers is that, if bad weather prevents

bees visiting the showy flowers, some seed is certain to set by the

cleistogamous ones. In the mountains this must often be the only seed

set.

The fruit

is a three-sided capsule and when ripe it becomes erect. On a dry sunny

day it splits into three by means of three valves. The seeds are then

collected into three boat-shaped compartments. The wall then dry and

contract, so squeezing the seeds together and eventually the inner ones

fly out, often to a considerable distance. As much as three feet has been

measured.

UMBELLIFEROUS PLANTS

Two

members of the great Umbelliferous Family are to be found in the Highland

pastures. They are the Spignel (Meum athamanticum) and the Sweet

Cicely (Myrrbis odorata).

They are

both very attractive plants and are highly aromatic; the leaves, stems and

rootstock containing sweetly smelling oils. The both possess large,

underground stems, which store up large quantities of foodstuff in the

form of starch and oily substances. This reserve allows them to commence

growth as soon as favourable weather returns in the spring.

They

produce a tuft of large leaves which are highly dissected. In the case of

the Spingnel, the leaf segments are almost hair-like, but the Sweet Cicely

they are very similar to those of the Common Cherbil or Cow Parsley so

common in the lowlands in spring and early summer. The tuft of spreading

leaves keeps competitors from encroaching upon the immediate surroundings

of the plant.

>From the

midst of the leaves arises a tall flowering stem, which in the case of the

Sweet Cicely may be three feet high and branched. The tall stems easily

overtop the grasses and other plants of the pastures. They are also very

strong with ribs of hard woody tissue running down the sides and they are

also hollow (and as we now tubular construction gives the greatest

strength with the least material). They are thus well able to support the

large flower heads and to withstand the wind which so often sweeps their

exposed habitat.

As the

summit of the stems and branches, are produced large heads of flowers,

constructed after the typical fashion of the Umelliers. From the summit

of the stem radiate several stalks or, as they are called, rays; in the

case of the Spignel there are ten to fifteen rays, whilst in the Cicely

there are rather more. Each ray reaches the same height and at its ummit

gives rise to a similar number of shorter rays, called the secondary

rays. Each of them produces a single flowers and as they reach the same

relative height the resulting head of flowers is a flat, table-like

structure. This form of flower head is called an umbel. In the above case

the flower heads are actually umbels are several spreading bracts which

help to impede creeping insects from reaching the flowers.

The

flowers are small with five white petals arranged around the fleshy summit

of the flattened ovary. This produces nectar quite openly upon its

surface and it is easily obtained by short-tongued insects. The large

numbers of flowers in each umbel make them very conspicuous and they are

visited by hosts of insects. Many kinds of lies, some beetles,

short-tongued bees, wasps, butterflies and hover-flies visit them At

first each flower is male only as the two stigmas are not mature until all

the pollen is shed. Large quantities of cross-fertilized seed are set.

Each

flower finally produces a single winged fruit containing two seeds. After

fertilization the ovary walls enlarge and produce a wing all round the

edge. The seed itself is surrounded by vessels containing aromatic oils

which help to nourish the embryo and protect it from damp. When ripe the

fruit splits down the middle and the wind transports the resulting halves

to a considerable distance supported by their wings.

It is

thus not surprising that the above two plants are common and well

distributed in the Highland pastures.

Viviparious Persicaria (Polygonum viviparous)

This

plant is quite common in grassy pastures and is closely related to the

Persicarias and Snake-weed of the lowlands.

It is a

lowly plant with a tuberous underground stem acting as a storage organ.

The stock

is crown by narrow leaves with very log stalks. They are smooth and

leathery in texture whilst the edges are recurved, thus covering, to a

certain extent, the under surface and preventing excessive transpiration.

The flower stems are about six inches high with a few small sessile

leaves. The flesh-colored flowers are produced in a close terminal spike

and are visited by flies and small bees, but are often self-fertilized.

Very

often, however, it will be noticed that the lower flowers are reddish,

bud-like objects. These are bulbils, which are easily detached and, on

falling to the ground, produce roots and leaves. This known as vegetative

reproduction or as it is sometimes called, vivipary. The advantage of

this to the plant is, that the long period of time between the opening of

the flowers to the setting of seed is dispensed with. This may be vital

importance in bad seasons when the flowers open late and cannot get

through the usual life processes before winter arrives.

Several

cases of vivipary occur among alpine plants. We have already come across

it in the Drooping Mountain Saxifrage and shall find that several grasses

have also adopted this short cut to reproduction.

It must

be remembered, however, that continued vegetative reproduction unsupported

by the formation of ordinary seed lead to the gradual weakening and

undermining of the race, and as we have seen, in the case of the Drooping

Saxifrage, to it eventual extinction.

Dwarf Juniper (Juniperus nana)

This is

quite a common plant in the mountain pastures and is probably only a

starved mountain variety of the Common Juniper which will be described in

Chapter XI.

It is a

very low shrub which has adopted as espalier growth and lies back against

the soil. In fact, it is often almost a carpet plant. In all other

respects, it is quite similar to the common Juniper.

In lowly

growth is, of course, an adaptation to climatic conditions, affording the

plant protection against strong winds and the weight of snow in winter.

LEGUMINOUS PLANTS

We have,

in the grassy areas of the mountain pastures of the Scottish Highlands,

three representatives of the Pea Family. They are the Alpine Milk Vetch (Astragalus

alpina),

the

Yellow Oxytropis (Oxytropis campestris) and the Purple Oxytropis (Oxytropis

Uranensis). The first two are rare plants, the former confined to the

mountains of Perthshire and the neighbourhoods of Braemar and Clova,

whilst the latter is only known in the Clova Mountains. The third plant

is rather more frequent, being often found at quite low levels, especially

near the sea. It is usually found on grassy mountain sides, growing on

stony patches and in rock crevices as well as among the short herbage.

Alpine Milk Vetch (Astragalus alpines)

This

small plant, with a creeping stem which may attain one foot in length, is

usually branched near the base. The branches give rise to several leaf

stalks which support compound leaves consisting of eight to twelve small,

oblong leaflets, with an odd one at the top of the stem. They are

slightly silky. From the axils of the leaf stalks arise long flower

stalks which are terminated by snort, close racems of bluish-purple or

white, tipped with purple flowers.

The

structure and pollination of these flowers will be found fully described

under the Broom (see Chap. XIV). In that same chapter, I shall deal with

the phenomenon of symbiosis in Leguminous plants.

It is

very rare and only those who know its actual flowering stations have much

hope of finding it.

Yellow Oxytropis (Oxytropis campestris)

This

plant is one of those very rare and very local mountain plants which, like

Lychnis alpina, elect to flower in one solitary spot in the

Highlands. Why this should be is a mystery, as there are many other

places equally suitable for its growth.

It is a

perennial with a short, tufted rootstock. The lower part of the stem is

covered with the old stipules and leafstalks of other seasons, which help

to protect the stock against frost and damp. The leaves and flower stalks

arise from the extremity of the stock. The leaves consists of ten to

fifteen pairs of small ovate leaflets with an odd one at the tip of the

main rib, and are hairy, especially on the lower surface, the stomata thus

being protected against excess transpiration. The flower stalks are

rather long and are terminated by a short spike of pale, yellow flowers

which are sometimes tinged with purple, especially in the lower part.

They possess a short, hairy clayx which protects the flowers admirably

whilst in bud.

After

flowering the Yellow Oxytropis produces short, swollen oval pods which are

produced to a fine point, and are covered with thick, black hairs which

protect the sees from rain and amp.

Purple Oxytropis (Oxytropis Uranensis)

This

plant is much more common than the other two Leguminous plants already

described, being frequently found on grassy mountain sides and sometimes

descending to sea-level near the sea.

It is

similar in habit to the Yellow Oxytropis, but is densely covered with

soft, silky hairs, and is hense much better protected against drought.

The flowers are a bright purple.

THE

POTENTILLAS

The next

group of plants, which is to be found in the drier areas of the grassy

mountain pastures, includes three plants of rather similar habit. The

first, the Tormentil (P. erecta), is an abundant plant in the lower

part of the pastures; it is, of course, a very common lowland plant. The

second, the Mountain Potenilla (P. alpestris), is a much less

common plant which is found here and there, especially in the southern

Highlands. The third, the Sibbaldia (P. Sibbaldia), is very common

in the higher pastures, often covering large tracts of the mountain sides.

Tormentil (Potentilla erecta)

This very

abundant plant is too well known to require a close description, but it is

cleverly adapted to dry situations.

It has a

thick, woody, perennial stock which is well able to defy the cold and damp

of winter, and from it arise several long, branched stems which may be

erect or procumbent at the base. They climb over surrounding vegetation

until, when they are clear of obstructions, the flowers are formed. They

are clothed with many leaves, the lower ones of which are stalked and

consist of five ovate, coarsely toothed leaflets which radiate like the

fingers of the hand. The upper leaves which are most exposed to the sun

and wind are reduced in size to limit transpiration. This plant is again

more or less silkily hairy.

The

flower stalks arise in the axils of the leaves and are terminated by

several small, bright yellow flowers, which usually have only four

petals. If we examine the flower, we shall find that in the centre is a

conical receptacle on which is situated a large number of one-seeded

carpels. Around this central disc are situated the nectaries, and around

them a circle of many stamens whose anthers face outwards. An insect

usually alights upon the centre of the flower and naturally leaves

transported pollen upon the stigmas, but on turning around to lick the

nectar ring it becomes dusted with pollen from the anthers. As they face

outwards and away from the stigmas the danger from self-fertilization is

small. The flowers set an abundance of small, light seeds which are blown

to a considerable distance by the wind.

Small

bees, flies and hover-flies are the chief visitors. A plant so well

adapted to conditions and setting an abundance of cross-fertilized seed is

well on the road to success. This explains why this plant is so common in

the lowlands as well as in the mountain pastures.

Mountain Potentilla (Potentilla alpestris)

This

plant is rather similar to the preceding. By some botanists, it is

supposed to be a distinct species, while others think that it is a variety

of the lowland plant, the Spring Potentilla. (P.verna).

As in the

case of the Tormentil, it has a perennial stock from which arises an erect

stem which may be eight inches in length. The lower part is clothed with

long, stalked leaves which consist of five to seven large, ovate, toothed

leaflets. The upper leaves are smaller, with short stalks and with five

or only three leaflets. They are covered with silky hairs which are

sometimes so abundant as to give the leaves a grayish appearance. The

flowers in this species are large, and of a bright, golden yellow, with

five petals, sometimes spotted with pink or white. They are much more

conspicuous than in the case of the lowland species. This is, of course,

related to the fewer insects such as bees in the higher area.

Scottish Sibbaldia (Potentilla Sibbaldia)

This is a

rather different plant from the foregoing. The perennial stock forms a

very dense, spreading tuft, clothed with small leaves consisting of three

wedge-shaped leaflets which are green, but hairy on both surfaces. The

tuft passes the rigours of winter beneath the snow whose weight its

structure is well able to support. The low growth and small hairy leaves

are, of course, adaptations against drought which may be very severe in

its exposed habitat. The tufts give rise to short, naked, flowering stems

which are terminated by small, greenish inconspicuous glowers, possessing

five very small yellow petals. The green calyces are the most conspicuous

part of the flower.

The

flowers do not produce nectar and, although they may be visited by small

flies, are probably self-fertilized.

THE

LADY MANTLES THE

LADY MANTLES

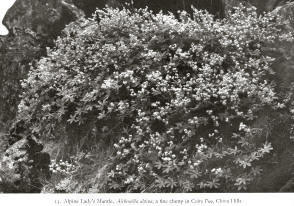

The most

frequent Lady’s Mantle to be found in the mountain pastures is the Alpine

Lady’s Mantle (Alchemilla alpina). It is sometimes very abundant,

forming large colonies, and can be met with at over 4,000 feet.

The

perennial stock sends out creeping runner with root at the nodes. The

flowering stems are usually creeping and attain six inches or more in

length. This stock is crowded with long, stalked radical leaves which are

divided to the base to form five or seven oblong segments or leaflets. To

guard against excess transpiration the stems and leaves are covered with

beautiful, shining, silver hairs.

The

flowering stems are terminated by spikes of small greenish flowers in

which there are no petals, the double calyx taking their place.

Another

alpine Lady’s Mantle is Alchemilla aseptic, which is much less

common but frequents similar places to A. alpina and may also be

found at over 4,000 feet. It is easily distinguished from the former by

its large, kidney-shaped leaves which are quite undivided. Its small,

yellowish-green flowers are produced in clusters at the summits of the

stems.

The

Common Lady’s Mantle (A. vulgaris) a frequent plant n the lower

pastures, has several varieties which reach 4,000 feet in the Highlands.

They are similar to A. alpestris

with

leaves of the same form, but they are covered with soft, downy hairs on

one or both surfaces. A further distinguishing character is the hairs on

the stems which spread outwards in A. Vulgaris, but lie flat in

A. alpestris.

Heart-laved Twayblade (Listera cordata)

This tiny

plant belongs to the aristocratic Orchid Family. This must come as

rather a surprise to my readers, for there is nothing very conspicuous or

unusual in the tiny spikes of brownish-green flowers.

One must

search for it carefully in the higher mountain pastures, for although I

have found it at only 900 feet in Lochaber, I have found extensive

colonies in the grassy hollows of the Cairngorms at nearly 3,000 feet,

nestling so deeply into the mosses and alpine herbage that they were only

discernible with difficulty.

The roots

of this plant consist of a mass of thin fibres and are not tuberous as in

most of our native orchids. From the stock arises a single, slender stem

to about six inches in height. About two inches up this stem are produced

two broad, opposite leaves which are never more than one inch in length

and are heart-shaped at the base. These are the only leaves that are

produced. The stem is terminated by a short raceme of very small flowers,

the upper petals and sepals of which are spreading, but the lip is long

and very narrow, cleft into two at the extremity and bearing two tiny

teeth at its base. I shall deal with the pollination of this orchid in a

later chapter.

GRASSES AND GRASS-LIKE PLANTS OF THE MOUNTAIN PASTURES

The

species of grasses making up the actual mountain pastures depend largely

on the soil and its water content. Where drainage is poor and the soil is

acid-peat with stagnant water, as occurs on large areas of the more gentle

mountain sides, then the grasslands are dominated by the Mat-grass (Nardus

stricta), which, as we have already seen, penetrates even into the

alpine zone.

Its

creeping rhizomes are almost on the level of the soil and the vast number

of individual plants dispute every inch of soil They creep over each

other, and as the under plants are smothered so a deep mass of dead

rhizomes and roots is formed. The thick, mat-like colony invades all the

surrounding pasture, until large area are under its sway. It is admirably

suited to its habitat as the thin, wiry leaves are little sough after by

grazing animals. Its roots contain a fungus which breaks down the peat

and humus and makes it available to the plant. Its huge colonies are

almost impenetrable to other species.

A

well-established Nardus grassland, however, usually furnishes a

habitat for one or two other grasses. Thus the Wavy Hair-grass (Deschampsia

flexuosa) is often found in the dense mats, its shallow roots finding

sustenance in the soil which collects around the tussocky Nardus.

This plant we have already met in the alpine pastures, so a further

description is unnecessary.

Certain

species of Agrostis, the Bent-grass, also grow in these areas, the

most common being Agrostis canina, a densely-tufted grass with

narrow, flat leaves. It also forms colonies by means of long runners.

Agrostis stolonifera, a similar species with rather wider leaves, and

A. tenuis, with difficulty distinguished from the latter, may both

be found with Nardus. They are characterized by their flowering

stems whose dry, stiff, erect remains are in evidence long after the

flowers have withered and the seeds have been distributed.

Where the

slope is greater and running clear water is in evidence, the Nardus

grassland gives way to that dominated by the Blue Moor-grass (Molinia

vaerulea). This also forms pure grasslands of great extent to the

exclusion of other species. It has a short rhizome giving rise to large

tufts of long, flat still leaves. The flowering stems bear two sets of

similar leaves, separated by a basal internode which acts as a food

store. The leaves are deciduous and drop off the plant in the autumn.

They, of course, form a dense humus which in time composes a soil dry

enough for other grasses to penetrate.

A

frequent colonist in this type of grassland is Deschampsia caespitosa,

which also forms dense tussocks of long, flat leaves whose rough edges cut

like knives if handled carelessly. It produces an elegant panicle with

many slender, spreading branches covered in silver-grey or purplish

two-flowered spike lets.

Another abundant grass-like plant in these areas is the Deer-grass (Scirpus

caespitosa).

This is

actually not a grass at all as it belongs to the Sedge Family (Cyeraceae).

It is also a densely tufted plant giving rise to a large number of erect,

green structures which might be mistaken for leaves, but are actually

steams. The leaves are reduced to short, brownish sheaths at the base of

each stem. The stems contain chlorophyll and carry on the photosynthetic

functions of the plant. Each stem is terminated by a tiny, ovoid, brown

spike of flowers.

A number

of read Sedges (Carex) are also found with Molinia, the

chief species being C. dioica, C. flava, C. panicea, C. Goodenowii

and C. stellulata.

Where

much stagnant water occurs, the Cotton Grass (see chap. XV) often

supplants Molinia.

Other

grasses of the mountain pastures are the Sweet Vernal-grass (Anthoxanhum

odoratum) already described in the alpine section. Sieglingia

decumbens is another common grass of tufted habit. It is usually from

six inches in height and its narrow nleaves have a few, long, soft, white

hairs on their sheaths and edges. It produces a small raceme of only five

or six spike lets, each of which contains three or four flowers.

The

Meadow-grass (Poa pratensis) is often present and it establishes

itself by means of a creeping underground rhizome and overground runners.

It thus colonizes large territories in a short period. It produces a

large panicle of slender, spreading branches covered with numerous small,

green spike lets. The Annual Meadow-grass (P. annua), so common

everywhere, is also found in the mountain pastures.

The

Fescue-grasses (Festuca) are often present and F. ovina is

often abundant, covering large amounts of land. Its variety F. alpina

was dealt with n the alpine section. It closely resembles it, but

does not form viviparous spike lets. The Red Fiscue (F. rubra), a

taller species with flat leaves and a reddish-panicle, is also widespread.

One

other grass-like member of the mountain pastures is the Heath Rush (Juncus

squarrosus),often found with Nardus. It is a tufted plant with

several stout, erect stems about one foot in height. The radical leaves

are very narrow and deeply grooved with the stomata on the inner surface

of the groove. The stems are terminated by a panicle of glossy brown

flowers. |