|

THE

MOUNTAIN PASTURES

The

Mountain Pastures comprise al that area of the mountain side having as it

lower limit the highest altitude attained by the pines, and it higher

limit that zone where such alpines as the Moss Champion, the Snow Gentian

and other typical alpines supercede the other vegetation. This limit is

much more arbitrary than the lower limit, but for the purpose of this book

we will take 3,000 feet as the mean height at which one enters the real

alpine zone. Nearly all the plants to be described in the ensuing

chapters will be found below this limit, although a few are also found at

higher levels.

The

vegetation of these wind-swept mountain sides consists largely of heaths,

sedges, rushes, and hardy grasses, while large patches of bog are common

everywhere. Rock patches, screes, etc., are found scattered throughout

the area.

We can

therefore divide the mountain pastures into three distinct divisions:

(a) the

rock, screes, etc., which dry out quickly, becoming hot under summer

suns. These areas support the drought-resisting species such as Sedum

Rhodiola, Dryas octopetala, and Antennaria diocica.

(b) the

grassy areas where we find such plants as Oxtropis Uralensis and

Astragalus alpines.

© the

bogs which are composed of peat soil which is saturated with water and

supports sphagnum mosses. Here we find such species as Rubus

Chamaemorus, Saxifraga stellaris, and Oxyria digyna.

I will

describe these three different zones separately. They contain many widely

differing species with many interesting devices adapting them to their

habitat and to their insect visitors.

PLANTS

OF THE ROCKS AND SCREES

Mountain Dryas (Dryas octopetala)

Among the

north-western Highlands, in one of the wildest mountain areas of Britain,

lies a group of mountains of austere grandeur. Here are the strange

pinnacled peaks of Liathach, Ben Eighe and Slioch, whose fretted sky line

stand out so magnificently against a blood-red sunset sky, and are

reflected in the waters of beautiful, island-studded Loch Maree which lies

glittering in the dying sunlight, the wind gently ruffling the birches and

pines that fringe its rugged shores.

There

mountains, composed as the are of ancient sandstones, limestones, etc.,

have weathered into many strange forms; pinnacles, battlement-like ridges

and needle-like peaks occur everywhere.

It is

among these mountains on limestone plateaux and dry, barren rocks that one

will find the huge carpets of the beautiful Mountain Dryas.

This

plant is a typical carpet plant. The roots are large and deep striking,

and above ground the stem is woody and often as thick as a man’s wrist,

giving rise to many woody branches which spread out across the surface of

the ground. The main stem attains a great age, as much as one hundred

years having been recorded. Each branch bears numerous tufts of small,

long stalked leaves which so cover the branches as to form a carpet. They

are crenately lobed, like oak leaves, and are glossy and dark green upon

the upper surface. Below they are covered with dense coat of white,

felt-like hairs, which are of course typical of plants growing in dry

conditions. The hairy felt also protects the stomata from the effects of

saturation in the spring when the snows melt and the ground is covered

with water. In the winter time they roll up so that the lower surface is

completely protected. They remain like this throughout the winter under

the thick snow mantle. This is an important factor with regard to a plant

which keeps its leaves for several years.

The very

conspicuous white flowers are produced singly on long peduncles. All the

floral parts are inserted on the disc-shaped receptacle. The calyx,

consisting of eight to ten sepals, is clothed with a black, hairy coat

which completely protects the flowers while in bud. The flower itself is

over one inch across and is composed of eight to ten white, glossy petals,

which in some plants may have a yellowish tinge. At the base of the

petals are inserted the stamens, which are very numerous. In the middle

of the flower is situated the ovary consisting of several carpels. This

floral construction is typical of the great Rose Family to which the White

Dryas belongs.

The

flowers are devoid of nectar, but the many stamens supply much pollen

which is sought by many different types of bees, such as mason,

leaf-cutters, etc. The many-flowered carpet is very conspicuous as the

Individual flowers are so large and showy. The stamens and the stigmas

mature at the same time, but as the stamens face away from the centre of

the carpels in the middle of the flower, this being the only place where

it obtains a good foothold, hence the pollen transported by it is

deposited on the stigmas. It does not then matter if any pollen falls on

the stigmas from the stamens, as cross-pollination has been effected.

As the

seed matures the style are prolonged into long, feathery awns. When the

seeds are ripe, each carpet separates from its neighbours and the seeds,

supported by the feathery awn, drift long distances on the wind to start

life far from the parent plant. Thus does Nature distribute its species.

This

plant is found chiefly in the north-west Highlands and in the north,

especially where limestone is found. It is not strictly an alpine plant

in Scotland, and is rarely found above 3,000.

THE

COMPOSITES OF THE ROCKS AND SCREES

The great

family of Composites is well represented in the mountain pastures of the

Highlands and at least six species are peculiar to the rocks and screes of

these vast areas.

They

include Alpin Flea-bane (Erigeron alpines), a very rare plant found

in the Breadalband Clova Mountains; the Mountain Everlasing (Antenmaria

dioica), very common in dry situations; the Alpine Hawk bit (Leontodon

pratensis), the Alpine Lettuce (Mulgedium alpina), only found

on Lochnagar and in the Clova Mountains, and there very rare; the Alpine

Hawkweed (Hieracium alpinum) and the Wall Hawkweek (Hieracium

murorum), whose alpine varieties are multitude and are a bugbear to

botanists.

Other

composites such as Gnaphalium supine, although common in the

mountain pastures, are also common to the highest mountain areas and have

been described under that heading.

Alpine Hawkweed (Hieracium alpinum)

Deep into

the heart of the western Cairngorms runs a wild glen, pine-clad in its

lower part but almost savagely beautiful in its upper reaches, where a

lonely lake nestles deep among the mountain precipices. Ancient moraines

block the valley, and a wild mountain torrent hurls itself down among the

rocks and boulders, as it rushes down into its gorge, deep hidden in the

black pines.

Beyond

lies lonely Loch Einich in a setting as magnificent and as savage as

anything in Britain. On one side rises the great bulk of Braeriach, his

head hidden in the clouds, while on the other side rise the great black

precipices of Sgorr Dubh which encircle the far end side of the valley;

sheer precipices which shoot up 2,000 feet from the lake shores, their

faces cut and scarred by innumerable rifts and water courses; precipices

so high that their shadow rests across the southern and western shores

perpetually.

This

lake, devoid of trees and surrounded by steep cliffs and fallen boulders,

is very lovely. At the outlet end of the lake is a beautiful crescent

beach of white sand surrounded by banks of stones and pebbles. These

stony banks and the precipitous shores are perfect collecting ground for

the mountain botanist and I have found many interesting plants in the

course of a scramble around it.

It was

here that I found the Alpine Hawkweed among the screes at the side of this

lonely lake, its large golden heads starring the somber, black patches of

pebbles and small boulders.

The

Alpine Hawkweed is a typical composite and detailed description will give

one a good insight into the reason for the amazing success of the

composites in the struggle for life.

The root

is long, deep-striking tap-root which reaches the moist layers deep down

where winter frosts cannot touch it and the summer droughts cannot destroy

it. This root is a storehouse for food, where, throughout the long

winter, energy is stored so that at the first opportunity the plan can

start forth into life. The rootstock is crowned by several oblong, green

radical leaves covered with long, white, silky hairs. The are presses

closely to the soil so that the stomata are in contact with the dampers

air near the soil, and are so arranged that no leaf is covered by another

and they receive the fullest amount of light and sunshine.

The

leaves, spreading outward as they do, prevent any other plant establishing

itself within their bounds. This is very important to the welfare of a

plant growing in regions where good soil is scarce and each inch of soil

must be fought for and held. The hairs on the under surface protect the

leaves from excessive transpiration.

From the

middle of the radical leaves rises a single flower stalk which attains

about nine inches in height. It is rough and covered, like the leaves,

with long hairs which are often rust colored. There are usually two or

three very small leaves on the stalk.

It is

terminated by a large head of bright yellow flowers, often over an inch In

width. It is a very interesting structure and well worth detailed study.

Below the head we notice what at first appears to be the calyx, composed

of many green sepals. Actually, this is not the calyx but an involucre,

the apparent sepals being really bracts which enclose the head of flowers

when in bud and protects the blooms from damp and cold. When the head

opens the involcre acts as a kind of fence against climbing insects, such

as ants, which have mounted the stalk in search of nectar. It is covered,

like the leaves and stalks, with long rust-colored hairs. Actually, there

are two rows of bracts, the outer one being much shorter than the inner.

Each head

of flowers contains many small, perfect flowers. If we dissect such a

head we shall find that each individual floret consists of a strap-shaped

corolla which is tubular at the base. It has four or five teeth on the

uppers edge, these corresponding to the five petals of ordinary flowers.

Around each floret, and springing from its base, are four or five fine,

silky, long hairs which form the real calyx. Within the tube of the

corolla are inserted the five stamens and the style. The corolla tube

arises from the summit of the ovary, which secretes nectar so abundantly

that the tube is often filled to the top.

In

composite flowers, the anthers mature before the stigmas and

cross-pollination is secured by the method known as the stylar-brush

mechanism.

If we

study a newly-opened flower, we shall find that the style is short and the

two divisions of the stigmas are pressed close together with their vital

surfaces inwards. The style and outer surface of the stigmas are hairy.

We shall also see that the anthers form a close cylinder around the

stigmas. The style commences to lengthen and pushed the stigmas through

the ring of anthers. On so doing the hairs on the stigmas brush the

pollen out of the anthers. At this time self-fertilization is impossible

as the as the two surfaces are pressed close together. As soon as all the

pollen has been brushed out, the stamens wither. The style having now

grown out beyond the mouth of the tube, the stigmas open out.

When a

bee arrives at a young flower and pushes its tongue down into a floret

tube to sup the nectar, the stylar brushes dust it with pollen. On going

to an older flower, where the stigmas are now mature, the bee will

pollinate many florets with the transported pollen.

When the

florets have been pollinated the flower closes and the involucres close

together to protect the maturing seeds. The calyx hairs lengthen and then,

one day, the Involucres open and the golden yellow flower will be found to

have been transformed into a globe of whitish down. Each seed Is

supported by long, white, silky hairs. Then the strong winds, which

precede thunder-storms, and the mountain breezes jerk them off the

receptacle and, supported by their silky parachutes, they fly away to be

distributed far from the parent plant. Thus new territories are invaded

in much the way the same way as in modern war.

The

Alpine Hawkweed flowers in mid-summer, but only opens its blooms in full

sunshine, closing them by night and in wet weather to conserve the pollen

from damp. At this season insect life is at its climax and the bright

golden blooms attract hosts of insects. Hive-bees, hover-flies, flies,

beetles and wasps are the flowers’ chief benefactors. Self-pollination,

however, takes place very frequently and often the ovules are fertilized

without the aid of pollen. This is known as parthenogenesis.

It Is

fairly common in the Highlands and is easily recognized. In certain

places, however, a variety occurs in which the leaves are broader and the

flower stems longer, while the involucre is covered with black hairs.

This variety has been named Hieracium nigrescens and is a link

between H. alpinum and H. murorum, which be described next.

Wall Hawkweed (Hieracium murorum)

This

hawkweed, which is so abundant on banks and walls and in woods and

thickets in the Lowlands, is also common in the Scottish Highlands. It

is, however, so modified by local conditions and by hybridization that a

multitude of varieties may be met with, many of which have been elevated

to the ranks of species by modern botanist. Over two hundred species of

British hawkweeds have been named, most of them being varieties of the

present plant.

The

common form of the Wall Hawkweed which may be found In the lower mountain

areas, but hardly penetrates very far into the higher regions, is, in

itself, very variable. There is a tap-root with a tough stock from which

springs a tuft of radical leaves. They are always stalked and are ovate

either with toothed edges or without any teeth at all, and some-times

taper into the stalk, at other times being quite-heart-shaped at the

base. Their upper surface is usually dark green and covered with short,

rough hairs, which, however, may be absent. Their lower surface is

usually of a pale green, often smooth, but sometimes downy.

The

flowering stem is often one to two feet in height and usually has one or

two small narrow leaves upon it. It is terminated by a corymbs of bright

yellow flowers smaller in size than in the Alpine Hawkweed. There are

usually only four or five flowers, but in some specimens as many as twenty

or even thirty may occur. The involucres and flower stalks are usually

covered with black glandular hairs interspersed with white or rust colored

down.

It forms

colonies on sides of precipices and on rocky hillsides, and banks on the

lower mountain slopes where its stem often projects at right-angles from

its steep habitant.

As we

tramp among the higher mountain pastures and glens, we shall encounter

many different looking hawkweeds which will be found to be varieties of

this plant. I have discovered several around Loch Einich. In one case

the flower heads were quite small, less than half an inch in diameter.

The leaves, stems and involucres were almost devoid of hairs. No stem

leaves occurred and the radical leaves were quite small and obtuse.

In

another example the stem was short and the flower heads large and reduced

to two in number. The involucres were shaggy and the whole plant much

more hairy than usual.

Enough of

attempting to depict the varieties of this very puzzling plant for they

are legion, and those who would know more about them must obtain one of

the monographs dealings with this very difficult genus.

Alpine Flea-Bane (Erigeron alpines) Alpine Flea-Bane (Erigeron alpines)

To find

this lovely plant, one must search the higher slopes of the wild mountains

surrounding the head of Glen Clova (an area famed for its rare alpine

plants) and among some of the higher Breadalbane Mountains. Unless one

know the more or less exact stations of this rare species it will be an

almost hopeless task, for it is very local, as well as very rare.

It is a

small plant, sometimes only two inches in height and never more than eight

inches high. The rootstock is perennial and buried deep in the soil. It

sends up a few hairy stems which are terminated by a single flower, or by

a corymbs of two or three flowers. At the base of the stems is a rosette

of several, lanceolate leaves which are covered with a coat of rough hairs

on both surfaces, and these well protect them against drought, when the

mountain sides are swept by biting winds or are scorched by the pitiless

sun. The stems usually produce a few small leaves.

The heads

of flowers are bright purple in colour and are about half an inch in

diameter. If we examine a head, we shall find that it is composed of an

involucre of several rows of imbricate bracts which are also very hairy.

The head is composed of two types of florets. The centre is occupied by

many, small, yellowish tubular florets and are very similar to those of

the Alpine Hawkweed, but they do not possess the strap-shaped corola. The

mechanishm with regard to fertilization is very similar to that of the

same plant. Around this yellow, central ring, we shall notice another

ring of many purple petals. These petals each represent a single floret

and are the advertising agents as by their conspicuousness insects are

attracted to the flowers. They also act, in co-operation with the

involucre, as a barrier against crawling insects who would like to steal

the abundant pollen and nectar.

The

florets of both rings are surrounded by a pappus of many hairs. These

lengthen after fertilization of the ovule to form a parachute to support

the ripe seeds in their flight.

Alpine Hawkbit (Leontodon pratensis

This is

another uncommon plat that I have found on the wild shores of Loch Einich.

It is also a composite and is related to the common Dandelion. Like it,

it has a deep-striking tap-root crowned by a tuft of long, narrow, deep

green leaves which are deeply pontific and are usually devoid of hairs,

although a few stiff ones may be found on the upper surface. From the

middle of the tuft of leaves rises a fairly tall flower stalk which is

smooth and fairly robust. At the upper end below the flower, the stem is

much enlarged and swollen. The involucres which taper into the flower

stalk are covered with black hairs and arranged in two or three rows.

The seeds

are not supported by simple hairs as in the hawkweeds, but by feathery

plumes.

The

Alpine Hawkbit is found fairly frequently in dry mountain pastures and

among screes, rocks and on dry banks. It may be only a mountain variety

of the Autumn Hawk bit (L. autumnalis) so common in the lowlands.

THE

ALPINE ROCK CRESSES

The

Alpine Rock Cresses both belong to the Arabis genus of the great

Cruciferous Family and are typical plants of dry, rocky clefts and screes.

Of these two plants the Alpine Rock Cress (Arabis alpina) is a very

rare mountain plant found on dry, rocky ledges of the Coolin Mountains of

Skye, and the Northern Rock Cress (Arabis petraea) is fairly common

in the western and northern Highlands. Both plants bring back pleasant

memories to me.

The

former I discovered on a blazing June day on one of the higher peaks of

the Coolins (that jagged ridge which closes in the beautiful Loch Coruisk

and Loch Scavaig with their strange loneliness and beauty, which when the

clouds are low on the Coolins can be weird and almost sinister), when the

azure sky was repeated in the rippling sea and all nature was at peace.

On such a day as this high up in a stone-filled gully which radiated heat

like an oven, I discovered this rare plant. It was growing from the

clefts of rock on the sides of the fully, a dry and arid spot where one

would scarcely have looked for plant life, although it would be wet enough

when the thick clouds hung around the tooth-like peaks.

It is

rather like the Hairy Rock Cress which is common enough in many Lowland

localities. It possesses a rosette of ovate, toothed leaves which are

hairy on both surfaces. >From the rosettes arise erect flowering stems

which are terminated by a raceme of fairly large, white flowers. After

flowering the flowers are replaced by a raceme of long, slender pods.

The

flowers, which secrete nectar, are visited by small bees and flies, for

whom the honey is easily accessible.

The

Northern Rock Cress I discovered late in May, on my first tramp through

that most magnificent of Highland passes, the Larig Ghru. Again I was

favored with a blazing sun which turned the Larig into a furnace of

unbelievable heat which burned one’s feet and beat fiercely off the

granite boulders into ones face. The higher corries of Braeriach were

filled with snow and sparkling cascades poured down the steep mountain

sides. As I gained the Pools of Dee, I looked back over Speyside, across

the Blackness of Rothiemurchus and the golden, broom-covered plain of the

Spey to where the blue sea shimmered off the coast of Morayshire.

The Pools

of Dee seemed so delightfully cool on this broiling day that I decided to

rest awhile upon their rocky edge. After bathing my face and hands in the

clear waters, I reclined on my back in the sunshine and as I did so, I

noticed that in the niches of the rocks were growing many tiny cress-like

plants. I dug out a whole plant and found it to be the little Northern

Rock Cress which had chosen those enchanted pools beneath the beetling

precipices as its home.

It

possesses a perennial stock with a long, slender root system which threads

its ways down into the interstices of the stones. The stock is crowned by

a rosette of pinnately cut leaves. From the leaf rosettes arise a short

stalk terminated by a small head of fairly large white or purple flowers.

As in the

case of the Alpine Rock Cress, the flowers are fertilized by small bees

and flies for which two tiny glands secrete nectar.

Hoary Whitlow-grass (Draba incana)

This

plant, which is allied to the Rock Whitlow-grass (see p. 29), also

possesses a rosette of long, narrow leaves covered with short hairs which

are either simple or stellate (several hairs commence at the same spot and

radiate from it in a direction horizontal to the leaf to form a star-like

pattern). So close are these hairs that the whole leaf has a hoary

appearance. This is, of course, a fine example of a drought-resisting

device and shows us why this plant is so much at home in dry, rocky clefts

and on screes.

The

rosettes give rise to tall flowering stalks which possess several small

leaves, also covered with many hairs. The stems are terminated by a head

of small, white flowers which are pollinated as in the case of the Rock

Whitlow-grass.

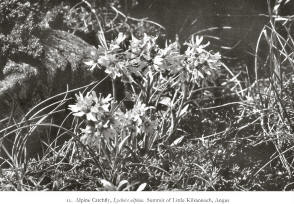

Alpine Catchfly (Lychnis alpina) Alpine Catchfly (Lychnis alpina)

This

beautiful mountain plant is peculiar in that it is to be found in one

solitary station in the Highlands and that, not some inaccessible corrie

whose precipices defy the mountaineer, or on the side of some steep crag,

but on an open wind-swept moor near the summit of Little Kilrannoch, a low

mountain top near the Clova region, so noted for its rare plants. Why

should this particular region be so rich in rare and local plants? Why

should Lychnis alpina and Oxytropis campestris, to mention

but two species, be confined solely to solitary stations there? These are

problems which will probably never be satisfactorily solved.

This

plant belongs to the beautiful Pink Family. It has a tufted perennial

stock which is clothed in long, narrow leaves, which are usually glabrous

or have a few long, woolly hairs in the lower part.

>From the

stock arise flower stalks which are seldom more than six inches high and

clothed with several pairs of leaves. They are terminated by a compact

head of about six pinkish flowers which are very beautiful and constructed

inexactly the same fashion as those of the Moss Campion which belongs to

the same family. They are similarly pollinated (see Chap. III). Bees and

butterflies are the flowers’ benefactors as they alone haves tongues long

enough to reach the nectar secreted at the base of the corolla tube.

Vernal Sandworm (Arenaria verna)

This

lovely little plant is of very restricted distribution in the Highlands,

due to the fact that it is confined to dry, calcareous rocks. This

explains its Perthsire habitat on the limestone schists of Ben Lawers, Ben

Lui, etc. It also occurs in Aberdeenshire and Banff.

It

possesses a very short, perennial stock giving rise to many short,

procumbent branches which give the plant a tufted appearance. This is

accentuated by the accumulation of old leaves and stems.

The

branches are densely covered with small, awl-shaped, opposite leaves whose

reduced surface cuts down transpiration and hence aids the plant to combat

its dry habitat.

The

flowering stems are erect and from two to four inches high. They produce

pairs of tiny leaves at intervals, and they usually branch. They are

terminated by tow or three white flowers on erect, slender pedicels which

are covered with short, viscid hairs. These prevent ants and other

creeping insects from reaching the flowers.

Each

flower consists of five narrow, pointed, greenish sepals which are shorter

than the five ovovate, white petals. Within the corolla are two whorls of

five stamens each and spherical ovary with three long styles.

The

flowers are visited by small bees and flies, but in the absence of their

visit’s the styles curve over among the stamens and self-fertilization

results.

Northern Bedstraw (Galium boreale)

This is a

common place of the screes, moraines and rocky places and is distributed

throughout the whole Highland area. It is, of course, a member of the

Bedstraw Family (Rubiaceae) and is the only typically mountain

species to be found in Britain, although one or two other species climb up

from the lowlands.

Its

rhizomatous stem creeps under the stones and rocks and gives rise to

erect, aerial stems which are rather more sturdy than in the case of the

lowland species. For this reason they have much less need of shrubs and

other plants to support them.

The stems

are four-angled, little branched and without the rough, prickly hairs of

most bedstraws. This is, of course, in keeping with its upright habit,

the curved climbing hairs of such species as the goose-grass not being

required.

The

leaves, which are lanceolate in form, are arranged in whorls of four at

intervals along the stems. They are rather thick in texture with a smooth

surface and three prominent ribs.

The

flowers are produced at the summits of the stems in large panicles which

contain numerous white blooms. These consist of four, very small, white

lobes, the tips of which curve inwards. The lobes are united to form a

very shallow tube on the top of the ovary. Within the tube are the four

stamens which spring from its side, and the inferior ovary surmounted by

two, short styles

The

flowers have a sweet, rather sickly perfumed and are much visited by the

smaller bees, flies, butterflies, and beetles. The stamens mature first

and, after shedding their pollen, they curl back from the centre of the

flower. The stigmas then become receptive, self-fertilization thus being

avoided.

The

fruit, which is green, two-lobed structure with one seed in each lobe, is

covered with hooked hairs and bristles. These catch into the fur or

feathers of passing animals and birds, and may travel long distances

before finally being brushed off. |