|

THE HIGH ALPINE CARPET PLANTS

We now come to the third type of alpine architecture,

i.e. the carpet plants. This type is fairly common in our mountains and

includes the Trailing Azalea (Loiseleuria procumbent), Reticulate

Willow (Salix reticulata), Dwarf Willow (Salix herbacea) and

the Alpine Bearberry (Arctostophylos alpina).

In carpet plants we find that the short stem is woody

and buried as far as possible in the soil. The root system is very

extensive and reaches down to the moister regions deep below the surface.

The short main stem gives rise to many branches that spread out close to

the ground. Each branch branches again, but the whole plant is prostrate.

In this way no other plant can grown within the circuit

of a carpet plant, and by continually extending its branches it ousts

other plants on the fringe of its territory.

All carpet plants are woody and are like very dwarf

trees that have been flattened out against the ground. Some of them live

for many years, fifty or sixty years being quite a common age.

We will not describe some carpet plants which are found

on our highest mountains at great elevations.

Trailing Azalea

(Loiseleuria procumbent) Trailing Azalea

(Loiseleuria procumbent)

This

beautiful alpine is widely distributed in the Highlands and one can be

sure of finding it on our highest mountains, wherever the slopes are dry.

I have walked through great beds of it on Ben Lomond in the south-west

Highlands, and have seen the side of Cairngorm pink with its multitude of

blooms. Wherever the slopes are covered in fine scree and are dry and

well drained, there one will find the Trailing Azalea.

It forms large colonies which carpet the mountain side

and, when in flower, gives quite a pink effect to the areas where it is

found. The tough woodsy branches of this plant are covered with small

leathery leaves, which are quite smooth on the upper surface, and are

interesting from the fact that their edges curl over. The stomata are

collected in lines between the midrib and the sides of the leaf. The

under side is coveted with short hairs which protect the stomata from

excessive transpiration, but to make quite sure that only necessary

transpiration takes place, the edges of the leaves curl over. This

curling of the leaf edges is common is the Heath Family to which our

present subject belongs.

At the termination of the branches one finds two or

three reddish-purple flowers in the axils of the leaves. They are small

and bell-shaped and contain five stamens. The ovary is situated at the

base of the corolla and the nectary is found at its base. The style is

longer than the stamens and hence the stigma protrudes beyond the

anthers. A butterfly arriving on a bloom must touch the stigma first and

will leave some pollen on it before being dusted by the anthers.

Cross-fertilization is thus ensured.

The Trailing Azalea is placed, by some botanist, in the

same genus as the Azaleas of the tropical and sub-tropical regions. thus

our small, lowly mountain flower can claim affinity with the gorgeous,

scented Azaleas which are such a spectacle in our greenhouses and

ornamental gardens.

THE CARPET WILLOWS

Everyone must be familiar with the Willows which are in

bloom at Eastertide in the Lowlands, although few people have taken the

trouble to notice how greatly they vary, and how many species, hybrids and

varieties we have in our lowland swamps, along the river-banks and in the

woods and copses. As we climb up from the Lowlands, we find that

tree-willows and the tall shrubby willows give place to small bush-like

shrubs. These become very dwarfed, until at last, when we reach the

highest plateaux and summits, they become typical carpet plants. They

belong to completely different species from the lowland and other mountain

species. They are the Reticulate Willow (Salix retculata) and the

Dwarf Willow (Salix herbacea).

To find them one must climb up to the high plateaux of

the Cairngorms, on the Ben Nevis massif and on the other high summits of

the Highlands, for these plants are very definitely alpine plants that

love the high, stony regions, where the lone eagle wheels and the wild

winds career eternally. Regions where many of us have passed some of our

happiest days, browned by the strong sun, lashed by rain and hail or

enveloped in white, cold mist as the clouds crept across the stony

wilderness like wraiths.

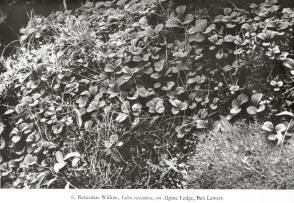

Reticulate Willow

(Salix

reticulata) Reticulate Willow

(Salix

reticulata)

This plant is a very typical carpet plant and often covers considerable

areas. Below ground is a large root system, while above ground branches

radiate in all directions, creeping closely to the surface of the soil.

These branches are covered by many large, elliptical leaves on long

pinkish stalks. The leaves themselves are dark green and highly polished

on the upper surface is coveted by a dense felt of bluish white cottony

hairs. The leaves are often rolled at the edges. This, with the cottony

felt, prevents undue transpiration. As this plant lives in dry, stony

places this is a very important consideration. When the leaves are young

and are more apt to be injured by cold, they are coveted on both sides

with thick hairs. As the leaf matures the hairs disappear from the upper

surface.

The flowers, of course, are different from those of the

other alpines we have studied. The male and female flowers are produced

on different plants and are wind pollinated, i.e the wind blows the pollen

from the male flowers on to the female flowers of another plant and thus

cross-pollination is procured.

The male flowers consist of dense catkins. The

individual flower consists of a single brown bract in the axil of which

arise two or more stamens. The catkin consists of a spike containing

dozens of these small bracts and their stamens.

The female flowers are in similar catkins but these, as

they contain no pollen, are not yellow. Each flower consists of a single

carpel in a brown bract and arranged in a spike.

After fertilization each female flower produces many

very small seeds, each seed having many short, silky hairs at its base.

When the seeds are ripe the wind detaches them and, supported by the

hairs, they may travel a considerable distance from the parent plant.

An interesting feature is that the catkins also contain

honey-glands and so they may also be pollinated by insects which visit

them for nectar.

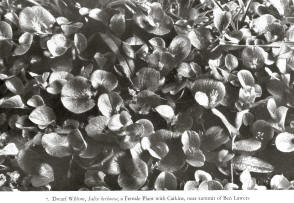

Dwarf Willow

(Salix herbacea) Dwarf Willow

(Salix herbacea)

This

little plant is often spoken of as the ‘smallest tree in the world’. Below

the ground there is a very extensive woody rootstock which may cover a

considerable area. It sends up short shoots covered with small leaves and

terminated by very small catkins, and forms a dense carpet.

The leaves are small, thin, very finely toothed at the

edges, without hairs and have a fine network of veins. The deep striking

roots reaching down to the deep regions where there is always moisture and

the small size of the leaves make the risk from drought very small, hence

the absence of hairs on the leaves.

The catkins are very short and contain very few

flowers. Parachute seeds are formed as in the case of the Reticulate

Willow.

Thus we see that even the great Salicaceae family has

managed to maintain a quite a vigorous, if dwarfed, existence in the

alpine regions.

Alpine Bearberry

(Arctostaphylos alpina)

This

is a plant of the plateaux and high mountain slopes of the north-west

Highlands. If the time be autumn, when the first powdery snows have

fallen and whitened the summits, we shall find that large areas of the

mountains sides are a blaze of red. These bright, flaming patches are

formed by the dying leaves of the Alpine Bearberry, which are shed each

year and beautify the mountain sides for a brief spell before their final

extinction.

If we dug up this plant, we should find that it

possessed a very large and complicated root system which pushed down into

the wetter and warmer layers beneath the surface. Above the ground we

should find that it possessed a strong, woody, main stem which was largely

buried in the stones and herbage and send out short creeping branches

densely covered in small, thin leaves which had a few small teeth around

the apex. Like the Trailing Azalea it is a carpet plant, but its branches

are more herbaceous than the woody stems of that plant.

The flowers are produced on short, drooping stalks,

which usually support from two to three, almost pure white flowers which

are ovoid in shape and crowned by the lobes of the united petals.

It is fertilized in the same manner of the

whortleberry and possesses similar horns to the anthers.

After flowering the corolla withers, whilst the ovary

swells and becomes fleshy to form a round, black, shining berry or drupe

which is eaten by such birds as the ptarmigan and grouse, which thus

distribute the seeds.

We have another bearberry in Scotland, but that is more

distinctly a plant of the dry moorland, under which heading it will be

described. |