|

THE HIGH ALPINE SAXIFRAGES

The Scottish Highlands are rich in Saxifrages and ten

species are to be found there. Some of them inhabit the lower slopes and

valleys, while other are widespread on the mountains themselves; five

species are more or less confined to the highest summits. They are the

Purple Saxifrage (Saxifraga oppositifolia), which, although not

confined to the highest regions, as it may be found at comparatively low

altitudes, is very common on our higher mountains; the Tufted Saxifrage (S.

caespitosa) only found near the summits of the highest mountains; the

Drooping Mountain Saxifrage (S. cernua) a very rare species only

found on the summit of Ben Lawers and now nearly extinct; the Alpine Brook

Saxifrage (S. rivularis) found beside streams and springs near the

summit of Ben Nevis, Ben Lawers and Lochnagar; and the Alpine Saxifrage (S.

nivalis) found not uncommonly on the higher Scottish mountains.

Of these Saxifrages, the first two are cushion-type

alpines and the others are rosette types.

While not as showy as many of the Swiss Saxifrages, our

Alpine Saxifrages are very attractive and interesting plants.

THE CUSHION SAXIFRAGES

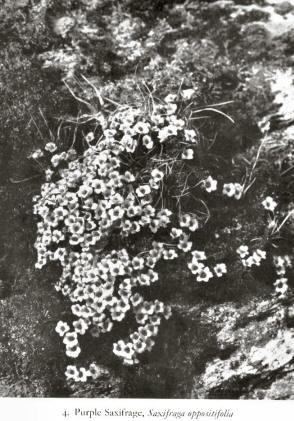

Purple Saxifrage

(Saxifraga oppositifolia) Purple Saxifrage

(Saxifraga oppositifolia)

This

is one of our most beautiful alpine flowers, and only those who have seen

it in bloom in its natural surroundings can have any idea of how lovely it

really is. Its large, purple blooms are to be found on the lower slopes

among the melting snows in early April, at a time when colour is almost

non-existent on the mountain sides. By May it is blooming wherever the

snow has cleared on the highest peaks and corries. By mid-June its

flowers have faded, and its seed is set and distributed long before the

snows of early autumn have arrived.

The Purple Saxifrage prefers most rocks and is found

more especially on the northern and eastern corries and slopes, where the

sunís heat is much less and water is more abundant. Its long roots

penetrate deeply into the cracks and crevices of the rocks, where they

escape the hard winter frosts and are able to tap the water supply in the

deeper soils.

Above the ground is a short, tough stem, which is

buried as far as possible in the soil. This stem give out slender

branches, which creep along the rocks giving out other branches which are

covered in tufts of leafy shoots. The whole system is very compact and

seldom rises more than on inch above the soil The result of this

compactness is the formation of dense cushion, which appears like a clump

of green leaves, the branches being absolutely hidden by the closeness of

the leaf tufts. The leaves themselves are evergreen, very small and shiny,

and arranged in pairs, each pair being closely pressed to the one above.

This helps us prevent undue transpiration.

The leaves are interesting in having evolved a very

ingenious device to check excessive transpiration. The leaves of plants

are usually covered on the under surface by pores, known as stomata, by

which the plant breathes, taking in oxygen and carbon dioxide which are

used in the respiratory and photosynthetic processes. Through these

stomata water escapes from the plant as vapour in the process of

transpiration. To get rid of surplus water, some plants, especially those

inhabiting wet places, possess special water pores of hydathodes at the

tips of the leaves, or at the point of teeth along the margin. The Purple

Saxifrage possesses such a hydathode at the apex of each leaf. To control

the escape of water, this plant, in common with some other species of

Saxifrage has a special mechanism. The tissue around the pore has the

power of secreting chalk. Water leaving the leaf by this pore dissolves

some chalk which is deposited on the surface of the pore. On dry days

when evaporation is rapid, a heap of chalk accumulates quickly and soon

closes the pore, preventing the exudation of any further water. At night,

when evaporation is less, the escaping water dissolves some of the

accumulates chalk and allows the water to exude again.

The amazing thing is, that although this plant grows on

rocks which contain little or no chalk, such as granite or gneiss, the

roots by reason of special selectivity are able to obtain enough chalk to

continually supply the chalk glands.

Each leaf tuft sends up a short stalk surmounted by a

beautiful, reddish purple flower, which is very large in comparison to the

size of the plant often being nearly an inch in diameter.

The individual flower is bell-shaped, the five petals

being united for more than half their length. The flowers, being large

and numerous almost hid the cushion thus making themselves very

conspicuous to insect visitors, which, as in the case of the Moss Campion,

are mainly butterflies whose long tongues alone can reach the nectarines

at the base of the flower, and for whom it holds out its reddish-purple

sign. Each flower contains ten stamens in two whorls. The ovary, at the

base of which are found the nectarines, is surmounted by two styles.

The stamens mature before the stigmas and a butterfly

must visit the newly-opened flower to be dusted with pollen. On visiting

an older flower the butterfly will leave some pollen on the now receptive

stigma. Thus cross-fertilization is assured and an abundant supply of

fertile seeds will be formed.

Tufted Alpine Saxifrage

(Saxifraga caespitosa)

This

species, like the preceding, also forms a cushion, but it is only to be

found at great heights and is much rarer. It cushions are not so compact

and leaves are short and green and divided into two or three lobes. These

leaves have no chalk glands as in Saxifraga oppositifolia.

In this species the flowers are small and white, and

one or two to each stalk. Each petal has a number of greenish veins

running down toward the nectaries. These veins guide the butterflies and

the flies which pollinate the flowers. The flower stalks are two to three

inches high and are covered with a glandular down as in some lowland

species. This acts as a barrier to crawling insects which would otherwise

mount the short stalk and steal the nectar, without giving any benefit to

the plant.

To find this plant we must climb to the highest summits

by way of the precipitous corries, where in the screes and rock clefts one

may have the good fortune to find its small flowers. It is practically

confined to the Cairngorm and Ben Nevis ranges.

THE ROSETTE SAXIFRAGES

We now pass from the Cushion Saxifrages to those which

belong to the Rosette group. In this series we again find the short main

stem or stock buried as far as possible in the soil. Immediately from the

top of this stock spread out compact rosettes of leaves pressed close to

the surface of the soil. This rosette arrangement is very common among

alpine plants. The leaves are arranged so that each one receives the

maximum of light and are pressed close to the soil. This makes it

impossible for another plant to grow within the radius of the leaves, an

important factor where competition for space is severe. The lowness of

the habit is very well adapted to the windy regions these plants inhabit.

The flowering shoot is long and upright and surmounted by the bloom. This

tall shoot protects the flowers from creeping insects and also makes the

flowers very conspicuous.

Droping Mountain Saxifrage

(Saxifraga cernua)

This

is one of our rarest alpine plants, being confined to the broken schist

formations near the summit of Ben Lawers, where it is becoming exceedingly

rare and very seldom flowers.

It is fond of damp, shaded rocks and does not exhibit

such marked modifications against drought as many alpines do. The very

short stock of this plant develops a number of small bulbs covered with

reddish-brown scales, in much the same way as the Meadow Saxifrage

(S. granulata) of the Lowlands. The likeness

between this plant and the Drooping Saxifrage has made some authorities

think that it is but a starved mountain edition of the same plant. The

bulbs are very easily detached and give rise to new plants. This method

of propagation is known as vegetation reproduction and is common among

alpine plants, being found in many widely differing families (Polygonum,

Poa, Deschampsia, etc.).

The stock is crowned by several radical leaves. These

are on rather long, weak stalks and are kidney-shaped (reniform) with

angular lobes and are almost glabrous on the upper surface. There are a

few short hairs on the under surface.

>From the midst of the leaves rises a fairly tall,

flowering stem which droops slightly at the summit. There are a few small

leaves on this stem and in their axils there are often small, brownish

bulbils, which detachment, give rise to plants as in the case of the root

bulbils. The flowering stem is crowned with one to three small flowers.

These are white, and each petal has several well marked veins which

converge on the nectary at the base and act as guides to insect visitors.

The chief visitors are bees and small flies.

Very often, however, the plant produces no flowers,

relying on vegetative reproduction to continue the species. This is

probably one reason for its increasing rarity and for the fact there is a

great danger of the plant becoming totally extinct. Vegetative

reproduction when not aided by cross-fertilized seeds must result in the

gradual undermining of the race and its eventual extinction.

Why this plant should be confined to Ben Lawers is

impossible to explain. Perhaps it was a happy accident that deposited its

seeds there in some distant past, who can tell? Some bird, perhaps, who

after a lost flight from the Arctic regions landed on this high peak and

left some seeds of the plant behind. Or, perhaps, its explanation can

only be found way back in the Great Ice Age. This is only one of the

many fascinating mysteries of the plant world, which will probably never

be explained.

Alpine Saxifrage

(Saxifraga nivalis)

To

find this uncommon alpine, we must climb into the wild corries and risk

our necks upon the cool, damp, north-eastern precipices of our highest

mountains. We may find it very rarely on Braeriach and Cairn Toul, and

more abundantly on the Ben Lawers and Ben Nevis Range. It may also be

found in Skye.

It possesses a very short stock which is of a hard,

tough structure. The toothed leaves are arranged in a close rosette on

the summit of the stock. They are of a leathery texture and obovate in

form, tapering downwards to form a stalk. The thick leaves are well

constituted to dry conditions, the fleshy tissues conserving water and the

thick cuticle reducing transpiration.

The flowering stems, which are from two to five inches

in height, are erect and unbranched and are hairy in the upper part. It

is usually naked, but sometimes bears one or two small leaves.

The four to twelve fairly large, white flowers are

collected together into a compact terminal head. The sepals are about the

same length as the petals. Within the corolla are situated two whorls of

five long and five short stamens and two styles.

The flowers, which secrete nectar, are visited by small

bees and flies. The long stamens move in towards the centre of the flower

and, when they have shed their pollen, they recede their place being taken

by the shorter ones. When all the pollen is shed and all danger of

self-pollination has gone the two styles spread apart and become

receptive. This is the mode of pollination inmost of the white and

yell-flowered Saxifrages.

Alpine Brook Saxifrage

(Saxifraga rivularis)

This

rare alpine is confined to the edges of brooks and springs near the

summits of Ben Lawers and Ben More in Perthshire, of Cairn Toul and

Lochnager, and perhaps one or two other summits of the Cairngorms, and of

Ben Nevis and Aonach Mor.

The short stock produces a few long-stalked, smooth

leaves, which are three to five lobed and resemble those of Saxifraga

cernua. The slender, flowering stems also possess several long-stalked

leaves of simpler form, the upper ones forming a pair of bracts below the

two or three flowers which are produced on short, slender pedicels. They

are small, the calyx being as long as the corolla, and as they are not

very conspicuous they are little visited by insects and are probably

self-fertilized.

Occasionally it produces bulbils in the axils of its

lower leaves and these resemble those of S. cernua. Thus in the

event of no flowers being formed in bad seasons, when the snows have lain

late, the plant can propagate itself vegetative by their means. |