|

The

Orchid Family contains the aristocrats of the plant world, with beautiful

and gorgeous flowers whose wealth of colouring and perfume is unsurpassed.

This

wonderful family contains some of the most marvelous devices to secure

cross-fertilization by the aid of insect visitors, and many orchids are

absolutely dependent on insects for the propagation of the species.

Our own

British orchids are naturally much less spectacular and conspicuous than

the great orchids of the tropics, growing under conditions of great heat

and humidity and amid abundant insect life which encourages a much greater

executive ability than our colder, less congenial climate.

All our

British orchids are geophytes, i.e. plants which root in the ground and

include two saprophytic types which, however, are plants of the woodlands.

In the

Highlands, we have eleven orchids, many of which are of common occurrence,

especially in the meadows of the valleys and lower hillsides.

They

include the Early Purple Orchis (Orchis mascula), very common in

damp meadows in early May and June; the Spotted Orchis (O. maculata),

very common in the meadows and heathy pastures; the Marsh Orchis (O.

latifolia), fairly common in damp, boggy meadows and pastures, where

one may also find its less common variety (O. incarnata); The

Butterfly Orchis (Habenaria bifolia), common in heathy pastures and

meadows; the Sweet-scented Orchis (H. conopsea), found in similar

places and just as common; the Small Orchis (H. albida), common in

heathy pastures, and the Frog Orchis (H. viridis), which may be

found in grassy meadows and on banks.

Besides

these meadowland species w also have the Creeping Goodyera, the Coralroot

and the Heart-leaved Twayblade which have been described elsewhere in this

book.

I will

endeavour in the ensuing description to describe the beautiful mechanism

by which some orchids obtain cross-pollination.

I will

commence with the Butterfly Orchis, in which the flowers are large and the

various organs of the flowers are easily discerned.

Butterfly Orchis (Habenaria bifolia)

Imagine,

if you can, a June day in Lochaber when the sun is shining in a cloudless

sky, and the soft wind blows gently up Loch Linnhe from the distant

islands, ruffling the mirror-like surface of the sea, whilst a lark is

singing high in the blue vault of heaven as he mounts steeply from his

well-hidden nest in the flower-starred meadow. The mountains rise steeply

from the sea, where their every feature is reflected in the azure depths,

towards the majestic bulk of Ben Nevis dominating the interior, his sides

slashed with slowly diminishing snow fields.

I am

standing in one of the small meadows which occupy the narrow strip of low,

fairly flat land between the sea and the steep mountain sides, and have

been wrested by the crofters from the bog and moorland with infinite

patience and toil.

These

meadows are naturally wet, and often boggy, and are intersected by the

numerous small streams that race down the mountains.

In the

south we are accustomed to see the meadows golden with Buttercups, or

white with Ox-eye Daisies, but here the meadows are filled with Orchids

and they are amazingly beautiful with the long purple spikes and handsome

spotted leaves of the Spotted Orchis and the delightful creamy spikes of

the Butterfly Orchis.

The

latter orchid is so called because the blooms are supposed to resemble a

butterfly. In this case, however, the name is not so appropriate as in

the case of the Bee Orchis of Fly Orchis, which are amazing imitations of

these respective insects.

In

Britain we have two types of this orchids; they are the Greater Butterfly

Orchis (Habenaria chlorantha), a large and very beautiful species

confined to moist woods and much more common in the south, and the Lesser

Butterfly Orchis (H. bifolia), the type so common in the Highland

meadows.

If we

were to dig up one of these orchids we should find that the short stem is

buried deep in the ground, and springs from a pair of white, fleshy,

tuberous roots, one of which is larger than the other.

The

larger tuber is a storehouse from which the present leaves and flowers

obtain their nourishment. This tuber was in existence the previous year,

whilst the other and smaller tuber is the store for nest year’s plant, and

stores up the nourishment obtained by means of its fibrous roots and the

leaves. Thus this plant can get to work to form leaves and flowers as

soon as conditions permit and independently of its fibrous roots.

Just

above the surface of the ground the Butterfly Orchis produces two fairly

large, glossy green leaves, from the middle of which springs the flower

stem. This tem has one or two scale-like leaves and its surmounted by a

dense spike of creamy, sweetly-scented flowers.

The chief

insect visitors to this plant are certain species of Hawk Moths, whose

long tongues alone can reach the nectar secreted in the long spur. The

cream-colored flowers are a good guide to those night flying insects, but

to aid them still more effectively the sweet, clove-like perfume is much

stronger in the evening than by day.

We are

now in a position to examine the individual flowers and see now they are

specialized for their insect visitors.

The

flower consists of six floral leaves, which are all petal-like and are

arranged in two whorls of three.

Of the

three outer ones, one is directed upwards whilst the other two are

spreading. Of the inner three, two are small and are situated in front of

the upwards pointing outer one. The third points downwards and forwards

and is known as the labellum. It is larger than the other segments and in

many species of orchis is the platform on which the insect visitors

alight. In this particular orchis, however, the labellum is hardly large

enough to accommodate large insects. Hawk moths hover before the flower

and have no need to alight in order to obtain the nectar, hence a landing

stage would be redundant.

The base

of the labellum is produced backwards to form a very long and narrow spur

at the base of which the nectar is secreted..

All

British orchids, except the very rare Lady’s Slipper, possess only one

stamen. The single stamen is united with the style of the ovary to form a

short column of which the anther is the apex and the stigma is the base,

and is situated directly over the entrance to the spur.

The

anther produces no pollen dust as in ordinary flowers, but tow club-shaped

bodies mounted on short stalks and attached by two adhesive discs. The

upper portion of the club is known as the polonium and consists of a mass

of pollen united together by elastic threads. When these pollinia are

ripe they are easily detached and may be removed by a needle to which they

attach themselves by the means of the adhesive discs. The polonium when

detached first stands erect, but shortly afterwards the stalk bends until

the club-shaped portion is pointing in a forward direction.

All these

specialized organs are designed towards cross-pollination. A moth seeking

to push its proboscis into the spur may quite easily detach one or both

the pollinia which adhere to its head or antennae. One can often trap

moths whose heads are covered with these small club-shaped bodies. Before

the insect arrives at another flower the pollinia have bent forward and on

its arrival are in the exact position to make contact with the stigma and

so effect cross-pollination.

It is

impossible for the Butterfly Orchis to be self-fertilized and it is thus

absolutely dependent on insect visitors. Almost all orchids are dependent

on insect for cross-pollinaton and often the scarcity or frequency of a

species in a particular area depends on the numbers of its particular

insect visitors in that area.

The plant

has also made sure that pollen from another plant shall fertilize its

blooms, and to this end has arranged its flowers in a spike.

The lower

flowers open first and a moth always commences at the bottom of the spike

and works upward to the higher newly-open flowers. From these upper

flowers it becomes covered with pollinia, which it transfers to the lower

flowers of the next flower it visits.

Another

feature which is common to most orchids is the fact that the ovary is

twisted and the whole flower is actually reversed so that in reality the

labellum is the upper petal.

Sweet-scented Orchis (Havenaria conopsea)

This

lovely little orchis belongs to the same genus as the Butterfly Orchis.

It is fonder of the wilder, more sterile pastures up to about 600 feet,

and in Lochaber is common in many such areas along with the Small Orchis,

Heaths, Sedges, etc.

It has

the same type of rootstock as the preceding except that the tubers are

divided into two or three lobes. The stem, which is about one and a half

ot two feet high, has several long, narrow leaves, and is crowned by a

dense spike of small, bright rose or purplish-red flowers which have a

very sweet vanilla-like perfume. The floral parts are small with a fairly

broad three-lobed lip. The spur is very long and slender, and is

obviously constructed to preserve the nectar for long-, very

slender-tongued insects such as the smaller types of hawk moths.

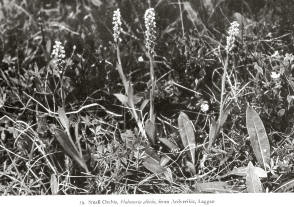

Small

Orchis (Havenaria albida) Small

Orchis (Havenaria albida)

This

species, although belonging to the same genus as the preceding two

species, is constructed rather differently. Instead of the tuberous roots

we find that the roots are composed of several thick fibres which may be

united, in some cases, into a deeply divided tuber. The stem is only six

to eight inches high and is clothed with a few small leaves which are

glossy in texture. The stem is surmounted by a dense spike of small

cream-colored flowers which are very sweetly scented. The flowers have a

three-lobed lip and a very short spur.

This

short spur indicates that shorter-tongued insects, such as bees, must be

the chief visitors for the nectar is easily obtained by them.

It is

quite a common flower in many of the lower pastures bordering the meadows

along the shores of Loch Linnhe and I have found it in similar situations

in many other spots in the western Highlands.

Frog

Orchis (Havenaria viridis)

The Frog

Orchis which, by the way, bears little resemblance to that animal, is

fairly common in the grassy pastures and meadows and is frequently found

in the Spey Valley.

It is not

an easy plant to find as its greenish flowers render it inconspicuous

among the grasses.

The stem

produces a few ovate, smooth leaves and is terminated by a close spike of

flowers. The sepals are large and form a head over the column. The lip

is long and hanging and of a yellowish colour. Nectar is secreted in a

little pouch near the summit of the lip just below and in front of the

stigma, and also by two lateral nectarines. The pollinia in this species

take a considerable time to become depressed, this being correlated with

the time lost in visiting three nectarines in each flower. The nectar is

accessible to short-tongued insects.

Spotted Orchis (Orchis maculata)

The

Spotted Orchis is a very common plant in the Highlands and one may find

its showy spikes of flowers in damp meadows, in rough mountain pastures,

on the edges of thickets and on banks and roadsides from sea level to

1,500 feet.

The

finest specimens of this orchis that I have ever seen were in a damp,

green meadow beside Loch Linnhe, where the steep hillsides leaves but a

fringe of level ground between their rough sides and the sea, and where

tiny streams run musically through the smiling meadows to the sea. These

field were filled with orchids, but especially with the Spotted Orchis

whose handsome spotted leaves and huge, beautifully marked spikes of

flowers made a scene of beauty so remarkable that I shall never forget

it. Scattered among them were the short purple spikes of the Early Purple

Orchis, the deeper purple spikes of the Marsh Orchis and the beautiful

scented spikes of the Butterfly Orchis.

The

Spotted Orchis possesses a fairly large, tuber-like root which is divided

into two or three lobes. This is the storehouse where energy for an early

commencement of life, after the cruel winter has passed, is stored. The

tubers send up a tall solid stem which attains a height of about one

foot. The leaves, which are mostly radical, are lanceolate in form with a

bright and shining surface beautifully marked with dark purple or black

spots. The flowers are formed in a dense terminal spike, which may be as

much as three inches in length in luxuriant specimens.

They vary

much in colour, sometimes being white, more commonly pale pink, and often

of quite a dark shade. The flower consists of three dark colored sepals

which are spreading. The upper petals form an arch over the column, thus

protecting the pollinia from rain The lip is broad and usually

three-lobed, much spotted and variegated with deep rose, or even purple,

and forms a find landing stage for insect visitors. It is produced

backwards to form a log spur which contains the nectarines.

The

pollination of these flowers is very similar to that of the Butterfly

Orchis. The flowers, however, are only faintly scented and their

colouring show that large bees and butterflies are the chief benefactors.

Especially the latter, as very few bees possess a tongue long enough to

reach the nectarines at the base of the long spur.

Modern

botanists now dive O. maculata into two species known as O.

ericetorum and O. Fuchsii. The first is confined to peaty

soils with an acid reaction and is the Spotted Orchis found on

moorlands and health places. It is distinguished from O. Fuschsii

by its broad, pyramid-like spike of flowers, and by the middle lip of the

flower being small and narrow and the spur slender.

O. Fuschsii prefer less acid soils and is the

Spotted Orchis of damp meadows and pastures. It is usually a taller, more

robust species than the preceding, with a cylindrical spike of flowers

which are much marked with dark purple lines and spots, whilst the spur is

stouter than in that species. A white form of great beauty occurs, but it

is very rare.

THE

MARSH ORCHIDS THE

MARSH ORCHIDS

The Marsh

Orchids are found in similar places to the Spotted Orchids, but also

prefer wetter places such as the marshy edges of lochs and streams. The

old botanists only distinguished tow species of Marsh Orchids, but today

they are divided into several species Two them, O. incarnata and

O. praetermissa, are locally common in the Highlands and are

sometimes accompanied by a third and much rarer species, O. pupurella,

which has a very limited distsribution.

These

species are not very easy to distinguish, and their diagnosis is

complicated by the fact that hybrids between the Spotted Orchids and the

Marsh Orchids are very common.

The

Crimson March Orchis (O. incarnata) is a beautiful species, and

when seen in masses, as one can often find it in boggy meadows, it makes a

fine display. It stands out well among the marsh vegetation, as its stems

often reach two feet in height and are terminated by dense, cylindrical

spikes consisting of many flesh-colured or pink flowers. The lip is

faintly three-lobed and its margin is reflexed and marked with dark spots

and streaks. A magnificent, rich purple variety occurs, but unfortunately

it is very rare; this the variety pulchella.

The

Common Marsh Orchis (O. praetermissa) is also fairly common in

certain parts of the Highlands, more so on the eastern side. It is

distinguished from the preceding by its darker colored flowers.

The third

species, O. purpurella , is distinguished from the other two by its

stem, which is more than half solid, and by its purple flowers and its

almost entire lip.

The

Early Purple Orchis (Orchis mascula)

This

orchis is another inhabitant of the moist meadows, but it is often found

in open woods and thickets. It possesses undivided tubers, which send up

stems to about one foot in height. The broadly lanceolate leaves are

spotted, although in some species these spots may be absent.

The

flowers are produced in loose spikes, which may sometimes be as much as

six inches in length. The flowers vary much in colour to flesh colour,

and even white. The lip, which is sometimes downy in the centre, is

curved down at each side and extended back into a broad spur.

They are

pollinated n a similar manner to the Butterfly Orchis, except that the

chief benefactors are bees and butterflies, especially bumble-bees. |