|

Amphibious Persicaria (Polygonum amphibium)

This is a

very common plant in tarns, streams and watery places, and its handsome

spikes of rose-pink flowers brighten the surface of the shallower waters.

As it forms large colonies the effect is heightened.

The

thick, hollow stems, which have much swollen nodes, creep along the mud at

the bottom of the pool. From the nodes are given off many tough,

much-branched, fibrous, reddish roots which anchor the plant firmly and

prevent it from being dragged away by currents. The creeping stem becomes

erect at the extremity, branches profusely, and rises to the surface of

the water. Here it produces several long-stalked, oblong leaves which

float on the surface and help to buoy up the stem. From the nodes more

branching roots hang down in the water and help to supply the large plant

with water and mineral salts.

If we

examined the leaf, we should see that at its base is a cylindrical,

membranous sheath which embraces the stem. This is actually the leaf

stipule, but it is known as the ochrea. We should notice that the leaves

are shiny above and it is on this surface that the stomata are found.

The

flowers are produced from the summit of the stem in dense spikes supported

on tall, stout peduncles. Each flower consists of a pink, bell-shaped

corolla, from the base of which arise four stamens whose long filaments

project beyond the mouth of the bell.

The ovoid

ovary is terminated by two erect styles with stigmas like pin-heads. The

surface of the ovary has a depression all round it and in this nectar is

secreted.

The

stamens mature before the stigmas and in a young flower the styles are

twisted together, but when all the pollen is shed, the anthers drop off

and the two styles spread apart. A bee on visiting the flower must push

its head into the corolla to reach the nectary and will leave transported

pollen upon the stigmas. Self-pollination is obviously impossible. To

ensure that bees will visit the flowers, the conspicuous spikes are

sweetly scented.

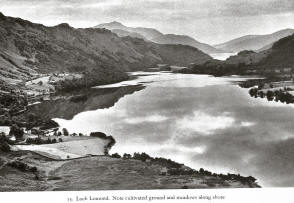

THE

INHABITANTS OF THE LOCH FRINGES

Having

described the inhabitants of the Highland lochs, we must now make the

acquaintance of some of the interesting plants that inhabit the shallow

edges and marshy shores of these delightful stretches of water. The

delta-like areas formed around the mouths of small streams which run down

into these lochs are especially rich in littoral plants.

In these

places we shall find the stately Yellow Iris, with its large, handsome

flowers, the beautiful fringed chalices of the Bog-bean, the bright blue

spikes of the Water Lobelia, the large Water Plantain with its spikes of

tiny flowers and many others, such as the Water Avens, the Marsh

Cinquefoil and the Meadow Sweet, which have been described elsewhere in

this book.

They

include many interesting plants and among them we shall find many

adaptations to habitat and insect visitors. A visit to the shores of any

Highland loch is very illuminating, offering as it does a chance to study

Nature under ideal conditions and amid beautiful scenery. All these large

sheets of water have a beauty of their own enhanced by the floral wealth

along their shores.

Let us

commence with a typical inhabitant of the shallow loch fringes, the Water

Lobelia.

The

Water Lobelia (Lobelia Dortmanna) The

Water Lobelia (Lobelia Dortmanna)

This

species is quite a common plant in the shallow water around the shores of

many Highland lochs. In Speyside it is very common in all the many lochs

of Rothiemurchus and it is there that I first made the acquaintance of

this lovely plant.

The Water

Lobelia usually forms a carpet of green leaves beneath the surface of the

water, sometimes completely submerged with a part of the leaves above the

water. The individual plant has a root system of fine roots which anchor

the plant in the mud and stones at the bottom of the lake. The rootstock

is crowned by a tuft of bright green, radical, cylindrical leaves, which

are very peculiar, for they are formed of two hollow tubes placed side by

side. As we know, a tube is one of the strongest forms of architecture

and thus, the leaves of the Water Lobelia are well adapted to withstand

currents and also the strong waves which often beat upon the shores of the

Highland lakes.

From the

tufts of leaves arise leafless flower stalks which attain a height of from

nine inches to one foot. They are terminated by a spike of three or four

distant flowers, the flower stems consisting of a single cylindrical tube.

The

flowers themselves are peculiar structure. They possess a tiny green

calyx from which protrudes the long tubular corolla which is slit open to

the base on the upper side. The tube is more or less two-lipped at the

entrance and irregularly lobed.

These

flowers show us the transition from the perfect bell-shaped corolla of the

Bellflowers to the strap-shaped tubular florets of the Composites.

At the

base of the corolla-tube we shall find the ovary and the nectarines. The

ovary is surmounted by the long hairy style, while in a newly-opened

flower we shall find that the anthers of the five stamens are pressed

close against the style. At this stage the three stigmatic surfaces are

pressed close together so that there is no chance of self-fertilization.

At a later stage, when the stigmas are well clear of the anthers, the

filaments retract and pull the anthers away from the style towards the

base of the tube, while the three stigmatic lobes unfold to expose their

receptive surfaces.

From this

description it is obvious that a bee visiting a flower will leave pollen

upon the stigmas at the entrance and then, as it pushes its head into the

tube, it will become dusted with pollen still adhering to the hairy

style. In this species, the flower is so well adapted that

self-fertilization is well nigh impossible.

Bees,

whose favourite colour is blue, are the chief benefactors as their tongues

alone are long enough to reach the nectarines, and as they must push their

heads into the tube to do this, they become dusted with pollen.

At the

same time, their habit of commencing at the bottom of a spike of flowers

mans that they will visit the older pistillate flowers at the base of the

spike first, thus assuring pollination with pollen from a distinct plant.

Thus do

we see how amazingly bees and flowers have evolved for the common good of

each other.

The

Bog-bean (Menyanthes trifoliata)

Along the

edges of lochs, tarns and streams, especially in shallow muddy places,

where inflowing streams have formed swampy deltas, we may find this

strange, beautiful, little plant.

I first

had the pleasure of studying its lovely flowers in a little pond covered

with Pondweed and fringed with Irises, Lousewort, and Marsh Cinquefoil, on

the edge of the sterile Moor of Granish in Speyside. Since then I have

found it in many different parts of the Highlands.

It is a

typical aquatic plant with a thick rootstock which creeps in the mud at

the bottom of the loch, sending out dense growth of matted roots into the

mud in search of food and anchorage. The rootstock sends up a thick stem

which in deeper water may float upon the surface, but in shallow water

creeps along the mud. The stem produces a dense tuft of leaves which have

along, thick stalk and a long, thick stalk and a long, white sheathing

base. The leaves consist of three large ovate leaflets, which are quite

smooth, as in most aquatics, and usually stand erect above the surface of

the water. From the base of the tuft of leaves arises the thick

flowerstalk which may attain as much as one foot in height. It is

leafless and crowned by a raceme of beautiful white flowers, which are

often delicately tinged with pink.

The

individual flower is an interesting and beautiful structure. It consists

of a short green calyx from the base of which arises the bell-shaped

corolla crowned by five deeply cut lobes which usually recurve. The outer

surface of the corolla is of a reddish hue shading to white and is quite

smooth, but within the petals are covered with a thick mantle of hairs.

These hairs prevent crawling insects and small insects with short tongues

from reaching the nectarines at the base of the bell. As these insects

would otherwise steal the nectar, and by their smallness miss the anthers

and stigmans, they could not benefit the plant.

If we

examine flowers from different plants, we find that in some the style is

long, the stigma occupying a position at the mouth of the bell and that in

these cases the stamens only arise half-ay up the inside of the bell. In

others, the stamens are long, reaching the mouth of the bell while the

style is short. This is the same construction as in the primrose and is

another example of heterostylism.

As with

that flower a full yield of seed is only obtained when pollen from the

long stamens is transferred to a long-styled pistil and vice-versa. Any

pollen transferred from the long stamens to the short-styled pistil will

be almost infertile. Thus has the Bog-bean ensured cross-pollination. As

this plant forms large colonies along the loch shores, the chance of a

legitimate transfer of pollen is great, for many flowers of the two types

will be found in close proximity.

Bees are

the chief visitors to this plant as only they possess a tongue long enough

to pass between the hairy filaments and reach the nectarines at the base

of the bell.

The

Greater Skull Cap (Scitellaria galericulata)

One

summer’s day I was exploring the boulder-strewn shore of Loch Lomond,

between Luss and Tarbett, where the craggy mountains drop almost sheer to

the water’s edge and where the shapely peak of Ben Lomond dominates the

landscape. Here, where one obtains charming views across the loch to

Rowardenan and down the island-studded lower portion towards Balloch, I

first discovered the Greater Skull Cap.

A little

stream came tumbling joyfully down the rocky hillside rushing into the

loch by a verdant mossy-green channel. Here large tufts of the Greater

Skull Cap with its beautiful deep blue flowers grew out from the chinks of

rock along the cool water course, and I was able to watch a large

bumble-bee diligently visiting each flower, unaware of the interest being

taken in it.

The Skull

Cap genus (Scutellaria), a member of the Labiate Family, is large

and widespread although in Britain we have but two native species.

The

Greater Skull Cap is a fairly frequent plant in damp rocky places beside

streams and rills, although I have not found it very often in the Highland

area, it is certainly common enough along the shores of Loch Lomond.

It

possesses a creeping rhizome which gives off fine roots which are well

able to push down into the crevices of the damp rock on which it loves to

grow. It sends up many weak stems which often hang down gracefully and

attain about one foot in length. The stems are clothed by many pairs of

sessile leaves which are ovate-lanceolate in shape and slightly toothed

and covered with a slight down. In the axils of these leaves arise pairs

of beautiful blue flowers which are produced along the greater part of the

stem and they all face in the same direction. Thus the inflorescence is

in reality a long interrupted spike. The corolla consists of a long tube

which is very slender in the lower part, but is much wider above, in order

to permit the bee to enter the flower. It is terminated by a pair of

lips, the upper one of which is concave, whilst the lower one is

three-lobed.

These

flowers, which are typical of the Labiate Family, are adapted for bees,

especially the larger types.

If we

dissect a single flower, we shall find that the ovary is situated at the

base of the slender tube where the nectarines are also situated. The

ovary is surmounted by a long slender style which is curved near the apex

in order to fit into the concave upper lip. The two stigmatic surfaces

project downwards. The four stamens lie parallel to the style in the roof

of the mouth, but two to them are shorter than the other two and lie

farther back. The concavity of the upper lip protects the anthers

beautifully against rain and damp.

At first

the anthers only are mature, but later after the pollen has been shed the

stigmas become receptive. A bee on visiting the flower alights on the

lower lip, and forcing its head into the mouth of the tube to reach the

nectar at its base, becomes dusted on the top of the head and the back by

the anthers in the upper lip. On going to an older flower with mature

stigmas, it is obvious that its pollen-covered head and back must come in

contact with the stigmas which are in the same position as the anthers

occupied. Thus cross-pollination is assured.

As only

the larger bees have long enough tongues to reach the nectar, they are the

only visitors. From their habit of visiting the lower flowers of a spike

first, i.e. the older flowers with mature stigmas, it is obvious that they

will always pollinate these flowers with pollen transported from another

plant or stem which is just what the plants wants.

This,

then, is another example of how amazingly flowers are adapted to their

insect visitors and how hard they strive to avoid self-fertilization.

Yellow

Iris (Iris Pseudacorus)

Most of

us must be familiar with the stately, purple, blue and white Irises, which

form such splendid beds in most ornamental gardens. Their erect posture

and their sword-like leaves enhance their military bearing, whilst their

velvety petal rival those of the Orchid in colour and form.

Our

garden Irises are, for the most part, natives of dry countries and do not

need more water than the other inhabitants of the garden. In this our

present subject is very difficult as it can only flourish where it can

obtain abundant moisture.

The

Yellow Iris is a very common plant throughout Britain and is quite common

in the lower parts of the Highlands. It prefers the shallow fringes of

lochs, the edges of streams and swampy places, whoever the soil is soft

enough for its roots to penetrate and where the soil is not too acid.

I found

it one June growing in profusion within a stone’s throw of the sea,

forming a dense mass of vegetation along the muddy edge of Loch Morar,

just where that delightful sheet of water hurls itself in showers of spray

into the Morar River to dash in impetuous glee into the nearby sea. From

this charming spot one looks out over the silver Minch to the sharp points

of Rum and romantic Coolins, and if the time be near sunset and the sun is

descending in crimson glory, few of Nature’s master pieces can rival the

magnificence of the scene.

The

Yellow Iris is a perennial and forms extensive colonies. Its main stem is

a thick, creeping rhizome which lies upon the surface of the mud and is

usually immersed several inches in the water. It gives off many thick

white roots, which penetrate deeply into the mud.

If a

rhizome is dug up and a transverse action is cut, it will be found to

consist of a sold white tissue containing many oval yellowish spots.

These spots represent the vascular bundles of the rhizome and contain the

vessels by which water, salts, and other food products are distributed to

the various parts of the plant. If a drop of iodine is placed upon the

section a deep blue coloration will be given, due to the abundant starch

grains stored up in the cells. During the winter this store of food

remains safely at the bottom of the lake, where frost and cold cannot

attack it.

The

rhizome sends out branches and in the course of time large areas are

colonized by a single plant. On decay of the intervening portions of the

rhizome, the daughter plants become independent of the parent. This is a

means of reproduction by vegetative process.

In the

spring, when the water begins to get warmer, a large bud at the extremity

of the rhizome commences to swell and, fed by the starch in the cells, it

sends up a bunch of radical leaves.

The

sword-shaped, very acute, rather glaucous leaves attain as much as three

to four feet in height and are remarkable for the fact that they possess

no under surface, but stand erect. They are very strong and are not

likely to be damaged by strong winds, and as they have a large surface

area, they are very efficient assimilating organs.

From the

midst of the leaves arise one or several tall, stout, cylindrical stems

upon which the flowers are borne. They bear very large, leafty bracts

very similar to the foliage leaves in form, and from the upper two or

three of which are produced the large showy flowers. Whilst young the

flower bud is safely hidden in the hollow sheathing base of the leaf.

Each

flower, when in bud, is beautifully wrapped up in membranous, translucent,

boat-shaped bracts, the one enveloping the other, but as the flower

develops, it gradually burst out of the sheath.

The

fully-opened bloom is a very beautiful structure indeed and can well claim

a place among our most lovely flowers. Only in the Orchid Family do we

find such a modification of structure and such nice adaptation to insect

visitors.

The

flower is large and complicated. The corolla (or as it is called, the

perianth) consists of six petals in two whorls, of which the three outer

ones have a large, broad, ovate blade which is bright yellow in colour.

The blade narrows into along claw which is united to the claws of the

inner petals to form a long tube. The lower portion of the blade has a

brown hart-shaped mark at its base, with deeper yellow colouring within.

Brown veins run down to the base of the claw and guide the bees to the

entrance of the perianth tube. These outer petals curve down gracefully

and form a fine landing stage for insects.

The three

inner petals are very small and much less conspicuous, the blade being

narrow, spoon-shaped, and bright yellow in colour.

If we

examine the flower, we shall see that in addition to the petals there are

three large, erect, conspicuous, bright yellow, petal-like objects which

curve upwards from the centre of the flower. These structures are

actually the styles and stigmas, the tip of the style being expanded into

a much-cut fringe below which and on the under side of which, is a tiny,

raised ridge which is the actual stigma.

Each

flower contains three stamens, whose anthers are produced under the

over-aching style which protects the pollen from rain and damp.

The ovary

is a smooth, cylindrical structure at the base of the perianth tube and is

concealed in the bracts. Nectar is produced by the glandular summit of

the ovary and it often almost fills the perianth tube.

To what

end has this beautiful, complicated structure been evolved? This is best

answered by gong to the nearest loch-side in June and watching the

bumble-bees at work. As we watch a particular bloom, we may be rewarded

by the flash of closing wings as the large insect alights upon the broad

outer petal. Without wasting any time and guided by the brown veins it

pushes its head down between the overhanging style and petal, any pollen

upon its head and back being scraped off by the ridge-like stigma. The

bee then brushes its back against the anthers. By this time it can push

its long proboscis into the perianth tube and suck up the nectar. It then

flies off to the next bloom with a good cargo of pollen upon its back

ready for the next stigma that it touches. Thus the flower has assured

cross-pollination.

After

fertilization the ovary swells to form a large ovoid capsule which splits

into three divisions to display the bright, orange-red seeds.

Purple

Loosestrife (Lythrum Salicaria)

This

beautiful plant is confined mainly to the western Highlands and does not

penetrate far into the northern Highlands. It is surely one of the

loveliest denizens of our marshlands, its tall, purple spikes dominating

the loch shores, river and stream sides and the wet meadows in full

summer.

It is a

perennial and possesses a tough rhizome which becomes quite thick and

woody with age and is anchored strongly by its many, tenacious, spreading

roots. Each year the flowering shoots die down, the stems of the next

season arising from buds produced upon the underground rhizome during the

autumn.

The

stout, flowering stems, which branch above, reach two or three feet in

height and are clothed with opposite pairs of long, lanceolate, soft downy

leaves which clasp the stem by their bases. The whole the upper part of

the stem and branches is occupied by a handsome spike of reddish-purple

flowers arranged in dense whorls, which are so close together as to give

the illusion of a continuous spike of flowers. A pair of leafy bracts

spreads out from beneath each whorl.

The

flowers are remarkable, not only for their beauty, but also for the fact

that it was from careful study of this plant by Darwin that it assumed an

important place in this theory of the origin of species.

The

flowers are remarkable, not only for their beauty, but also for the fact

that it was from careful study of this plant by Darwin that it assumed an

important place in his theory of the origin of species.

The

flowers possess a cup-shaped calyx-tube from the summit of which six or

seven teeth project. It is usually twelve-ribbed, each rib being covered

with long, upward-pointing hairs. From the top of the calyx-tube arise

five, six or seven spreading, narrow, purple petals which have deep red

veins acting as honey-guides. The twelve stamens spring from the

calyx-tube in two whorls, the stamens of one whorl being longer than those

of the other.

In some

plants one set of stamens is short and the other intermediate in length;

in others one set is intermediate and other is long; whilst in other one

set is long and the other is short.

From the

bottom of the calyx-tube arises the conical ovary, terminated by the style

with its knob-like stigma. Around the base of the ovary is a glandular

ring which secretes nectar.

Corresponding to the three different sets of stamens, we have three

different styles, i.e. short, intermediate and long, but we should also

remark that a short style does not occur in a flower with short stamens,

nor an intermediate style in a flower with intermediate stamens and

similarly in the case of the long style.

Having

plucked three spikes, each of different type, let us carefully examine the

pollen and we shall find that that of the long stamens is large-grained

and green in colour, whilst that of the short stamens is yellow and

small-grained, the medium stamens having pollen of an intermediate type.

A

bumble-bee visiting a long-styled flower must alight upon the stamens and

style as no other landing stage is offered to it, and on so doing its

hairy abdomen touches the stigma. It then pushes its head into the

flower, brushing the medium stamens with its thorax, whilst its head

touches the short stamens in the calyx-tube. If it now visit’s a

short-styled flowers, its abdomen will be covered with pollen from the

long stamens, its thorax from the medium ones, whilst as it pushes its

head down the calyx-tube, it will touch the stigma hidden within and will

leave upon it pollen from the short stamens of the flower previously

visited.

If we

catch one of these bees and examine its under surface, we shall see that

its abdomen is colored green with pollen from long stamens. Its head is

covered with yellow dust, whilst its thorax is greenish-yellow, these

colours corresponding to the different lengths of stamens.

My

readers who have had the patience to follow me thus far must be wondering

why such a complicated plan has been evolved. Darwin asked himself the

same question over eighty years ago and obtained the answer by careful

experiments. He proved that without insect visitors no seed was set. He

also shoed that in a long-styled flower very little fertile seed was set

if the stigma was pollinated with pollen from short or medium stamens.

Abundant fertile seed was set, however, if the stigma was pollinated with

pollen from long stamens. He obtained similar results in the case of

short and medium styles.

Now

through the peculiar arrangement of the flowers cross-pollination is

practically certain and there is a three to one chance of being arrived

at. We can realize how marvelously insects enter into the flower’s plan

and we can realize the joy of Darwin when his months of careful research

were so amply rewarded.

OTHER

PLANTS OF THE LOCH FRINGE

Many and

varied plants compete with each other for the limited space available in

the shallow waters at the loch’s edge, among them being many tall

grass-like plants.

Here we

shall find the tall, stalwart Cat’s Tail or Reedmace (Typhalatifolia).

This plant, which forms dense masses of stems and leaves on the marshy

edges of many lochs and ponds, has a thick, creeping rhizome giving rise

to erect stems, often over six feet in height, and clothed with many very

long, sheathing, grayish-green leaves.

Owing to

the height of these plants, the water in which they live is in deep shade,

and hence very few plants can thrive in a colony of Reedmace.

The

flowers are produced in the well-known club-shaped ‘bullrush’. This is a

huge spike of small flowers, the upper portion of which consists of

stamens, the lower portion of ovaries surrounded by tufts of soft, brown

hair. They are wind pollinated.

Another

plant of this ‘Reed Zone’ is the Erect Bur-reed (Sparganium erectum),

a close relative of the Floating Bur-reed already described. The

rootstock gives rise to long, fleshy runners which creep long distances in

the mud at the bottom of ponds and lakes.

The stem

attains two or three feet in height and is covered by long, spreading,

narrow leaves which are triangular in cross section.

The

wind-pollinated flowers are produced on naked branches in spherical,

sessile inflorescences. The upper consist of male flowers only, the lower

ones of females only.

Another

common inhabitant is the Common Water Plantain (Alisma

Plantago-aquatica). It possesses a very short, corm-like rootstock,

which is rooted in the mud by thick, fleshy roots. From the summit of the

corm buds are produced from which spring the leaves and flowering stalks.

The

leaves are produced on very long petioles which support the large, ovate,

deep green, smooth blades in the air well above the surface of the water.

From the

midst of the radical leaves arises a tall upright stem often attaining

three feet in height. This develops a complicated and rather beautiful

inflorescence, in the upper part of which whorls of branches are given

off, and from each of them a further whorl is produced, the whole forming

a pyramidal panicle clothed in hundreds of dainty, pale rose flowers.

The whole

plant, with its masses of bloom and large, long-stalked leaves, is a quite

distinctive and characteristic plant and cannot be confounded with any

other member of the loch flora.

Each

flower resembles that of the Ranunculus although actually widely separated

from that plant. The calyx is formed by three concave green sepals, the

corolla of three rose-colored petals of a very delicate texture and with a

yellow spot at the base. The ovary resembles that of a Ranunculus very

closely and is surrounded by a ring of stamens. The flowers produce

nectar and are visited by small bees and flies.

Several

species of real Rushes (Juncus) occur on the lake shores, the

Common Rush (Juncus communis) being very abundant. The tall, cylindrical,

smooth, green stems each producing a dense panicle of brown flowers near

the summit are too well know to warrant a close description.

The

rootstock gives rise to long, creeping runners which produce further tufts

of stems and thus new plants are produced vegetative.

It is

remarkable in possessing no actual leaves, these being reduce to brown

scales at the base of the stems. The brown star-shaped flowers, with

their six ovate, pointed sepals, their three to six stamens and their

three feathery styles, are constructed for wind pollination.

A similar

plant is the Hard Rush (Juncus effuses), which may be distinguished

by the deeply channeled glaucous stems of a harder and stiffer texture

than those of the Common Rush. It is almost equally common.

A rather

different plant is the Jointed Rush (Juncus articulatus) which has been

divided into several sub-species and varieties. The stems are weak and

spreading and are clothed by sheathing, cylindrical leaves. If these be

dried, they will be seen to have a jointed appearance, as they are divided

internally by cross walls of pith.

The

flowers are produced in large, terminal panicles and are similar, in

structure, to those of the Common Rush, but always possess six stamens.

It is found on the damp shores of lochs and ponds as well as in marshes

and bogs.

We may

also find the strange little Toad Rush (Juncus bufonius). This

plant is an annual and forms a dense tuft of pale green, weak stems with

several short, cylindrical, radical leaves at their base. The flowers,

which are usually solitary or may be three to four together upon the

branches, are pale green in colour and remarkable for their very pointed

perianth segments.

Many

species of Sedges may be found along the lake shores. The Club Rushes (Scirpus)

are conspicuous in forming very large colonies. Each plant has a long,

creeping rootstock giving rise to tufts of upright, cylindrical, green

stems without leaves. The green stems are the photosynthetic organs,

containing chloroplasts, as do the stems of the Common Rush.

The

wind-pollinated flowers are produced in dense, ovoid heads at the summits

of the stems. They contain three stamens on long slender filaments and

two spreading feathery styles. The genus Scirpus contains a large

number of species which are very similar to one another.

The

ordinary Sedges (Carex) are well represented and include a vast

number of species which are beyond the scope of this book to describe.

Among

common grasses may be mentioned the Flote-grass (Poa-fluitans)

whose weak stems creep over the mud or float upon the water, the long pale

green leaves being usually floating. The flowers are produced in a long

spike of spike lets each containing eight to twenty flowers.

The

Common Reed (Arundo Phragmites), a stout perennial often over six

feet high, forming large colonies, may often be met with. The stems are

covered by long, broad leaves resembling those of a Bamboo. The panicles

of flowers are very large and conspicuous, and are composed of hundreds of

purple-brown spike lets. As the seed ripens, it becomes surrounded by a

mass of silky hairs which give the panicle a silvery appearance and act as

parachutes when the seeds are born away upon the autumn gales.

The Invertebrate Fauna of the

Inland Waters of Scotland

Part III. By Thomas Scott, F.L.S. Loch Morar, Inverness-shire (1893)

(pdf) |