|

What

would the Highlands be without their glorious lochs, which glisten like

silver in ever hollow and valley? What pen can depict their beauties?

Loch

Lomond, where the rocky islets float like swans upon the scintillating

water; Loch Maree, nestling neath the strange peaks of Slioch and Ben

Eighe; Loch-an-Eilean, lying like a diamond upon the black mantle of

encircling pines; savage Loch Einich and Loch Avon, imprisoned by grim

precipices, the relics of a far away prehistoric world; the hundreds of

small tarns breaking the brown monotony of desolate moorlands and mountain

side, or appearing like oases amid sterile wastes of stone and debris, as

the beautiful Pools of Dee in the Larig Ghru.

Beautiful

as are these lochs scenically, they are also extremely beautiful and

interesting in themselves. Many of them, especially the smaller tarns,

are gardens of beauty wher the pure white chalices of the Water Lily and

its golden-hued cousin attract and hold the eye of the passer-by with

their sheer loveliness, while the Water Crowfoot, the Water Lobelia and

the Bog Trefoil enrich Nature’s delightful garden. Even below the surface

are mossy green pastures of Water Milfoil, Hornwort and Pondweeds where

the fishes glide amid the snake-like stems.

In this

chapter, I intend to describe the various floral inhabitants of these

delightful stretches of water, and show how marvelously they have been

modified to enable them to live in the strange element they have chosen as

a home.

We shall

find that the loch flora can be divided into three clearly defined groups.

The first

consists of those plants which live entirely in the water with only their

flowers or specialized floating leaves above the surface. They include

such plants as Water Lilies, Pondweeds, Water Milfoils, Water Crowfoot,

etc., which live in fairly deep water.

The

second consists of those plants that live along the shallow loch shores,

usually with their roots below water and the leaves and flowers above.

They include such plants as Water Lobelia, Water Plantain and Bog-Ban,

which form a fringe of verdure and beauty around the lochs.

The third

consists of those plants which prefer a moist habitat, but are unable to

live with their roots in the water and are found the bank and interstices

of loc side rocks beyond the reach of serious inundation. They include

such plants as the Mars Willow-herb, Marsh Valerian, etc., which are

actually marsh-land plants, and have been described in Chapter XVII.

COMPLETELY SUBMERGED AQUATIC PLANTS

Several

plants have become so adapted to watery conditions that they can live

submerged below the surface, only sending up flowering shoots in the air.

As we

have already seen, oxygen s a vital necessity for plants as it is for

animals. The oxygen taken in during respiration is used for the oxidation

of food substances and the subsequent release of energy provides the

necessary stimulus to growth and other vital processes.

It may at

first appear impossible for plants to respire in water, but we must

remember that water contains much dissolved oxygen, which is absorbed by

the leaves and stems. No stomata occur on the leaves as these would allow

entry of water and would result in the death of the plant, hence the

dissolved gas is just absorbed by the epidermal cells.

Thus we

see that it is possible for plants to respire although submerged and we

see that one condition of life is satisfied. But what about the

absorption of carbon-dioxide so necessary in the production of sugars and

starch by the process of photosynthesis?

Here

again, owing to the solubility of carbon-dioxide in water, the plant is

able to absorb enough for its requirements, and it can also use the

carbon-dioxide given out in respiration.

The

leaves and stems of water plants contain chlorophyll, even in the

epidermal cells, and they are thus able to synthesize sugars during

daylight, in the same way as land plants do.

If we

examine the stems, roots or leaves of aquatics under the microscope, we

shall find that their tissues consist of large, empty spaces traversed by

chains of cells; in fact their tissues are like a sponge, the empty spaces

of which are filled with air, or rather oxygen, given off during

photosynthesis. The reason for this is, that the roots and the stems are

often imbedded in waterlogged mud where no oxygen exists, and, as they are

therefore unable to respire, would eventually die. By means of the

internal air passages, air is able to reach these buried organs and keep

them aerated.

The

problems faced by aquatic plants are many. The amount of light is less

below the surface, and this further decreased by the presence of

impurities and of other water plants such as Algae, Duckweed, etc. For

this reason chlorophyll occurs in the epidermal layers of the leaves, so

that the plant may profit from all the available light.

Then

again, one must take into account the action of currents, which would tear

ordinary leaves to shreds. For this reason most aquatics have tough,

leathery leave which are often cut into fine segment which branch out in

the direction of the currents and offer little resistance to the their

passage.

Nearly

all aquatics, except Duckweeds and Frog-bit, have their roots in the mud

at the bottom of the lochs and obtain nutriment from the soil like

ordinary plants. The depth of the water determines the size of the plant,

as the aquatic send up long, slender, leafy branches to just below the

surface where the light is strongest. Thus many aquatics have stems of

great length, often attaining as much as four or five feet.

Finally,

most aquatics flower above the surface of the water, the branches sending

up long peduncles into the air where the flowers open and are

cross-pollinated. After fertilization the peduncles often curve

downwards, so that the seeds are formed below the water.

The

origin of the aquatic flora has been much discussed, but opinion inclines

towards the theory that aquatic plants have descended from ancestors who

were ordinary terrestrial plants. We may look upon them as pioneer

colonists, whose ancestors decided to make their homes in the watery

medium. They may have done so because of pressure from more virile

competitors, who forced them to take to the water in order to survive, in

the same way that early colonists forced the native tribes into the

inhospitable mountain regions. Or, we may liken them to adventurers

pushing out into unknown territory and leaving the safer, more hospitable

regions for more timid, less enterprising types.

Most

families of plants have certain aquatic or water-loving species, but it

will be noticed that the more recent families have few or none. Thus the

composites, the most numerous and the most modern family, possess very few

real aquatics. This shows that the aquatic habit has evolved

comparatively late in the life of the family and points to the fact that

it is an acquired habit.

Water

Milfoil (Myriophyllum)

In

Britain we have two principal species, viz., Myriophyllum spicatum

and M. verticillatum. They may be found in almost all of our

Scottish Highland lochs.

The

former is a typical under-water aquatic and forms mossy, dark green beds

which reach to the surface of the loch. If we examine a bed carefully, we

shall find that the individual plants which make it are rooted firmly in

the mud at the bottom of the loch.

The lower

perennial stems creep through the mud, giving out fine rootlets at the

nodes, these obtaining all the nitrogen and salts required by the plant.

The

creeping stem sends up fine branches which ascend almost to the surface

and are usually much branched themselves, and are covered in whorls of

four or five pinnate leaves composed of six or seven hair-like segments

which give a mossy effect to the plants when crowded together in the

water. These fine segments present a large aggregate surface to the

water, although presenting little opposition to its passage.

The

leaves absorb the dissolved carbon dioxide from the water and this, with

the action of the chlorophyll and sunlight, forms sugars. They also give

out oxygen as terrestrial plants do in sunshine, this action also give out

oxygen as terrestrial plants do in sunshine, this action being of great

biological importance, for as we know, animal life is continually

breathing out carbon dioxide, organic acids and bacteria. In the

comparatively still waters of ponds and lakes, the gradual solution of

carbon dioxide and the continual concentration of bacteria, etc., would

make the water unfit for life.

Fortunately the plants, by absorbing the carbon dioxide and giving out

oxygen, fulfil a dual purpose by clearing the water of excess carbon

dioxide and by supplying oxygen which kills harmful bacteria and keeps the

water pure and sweet. This beneficial effect is strikingly exhibited in

an indoor aquarium which can only be made a success by the introduction of

aquatic plants.

Each

branch of Myriophyllum spicatun is terminated by a slender spike of

small green flowers, which gradually lengthens until the little heads of

flowers project beyond the surface of the water into the fresh air and the

sunshine, where they open and are fertilized.

If we

examine the flowers we shall find that the lower ones are female and the

upper male, but none of them are perfect. The male flowers consist of a

small greenish calyx and four minute greenish petals, the stamens having

very short filaments with long anthers which project beyond the sepals and

petals. When ripe their pollen is distributed by the wind, their position

at the top of the flowering stem thus being very advantageous.

The

female flowers have no petals and are very small with four tiny stigmas.

After fertilization each flower forms a very small round capsule which

ultimately breaks into four sections, each with a seed inside. These

sections are drifted by the currents and gradually becoming waterlogged

fall to the bottom to form new plants, perhaps far from their parent.

We may

sometimes discover in our Scottish lakes the other species of Water

Milfoil (Myriophyllum verticillatum). In this species the flowers

are found in the axils of the upper leaves and are always immersed in

water. Otherwise the plant is difficult to distinguish from M.

spicatum.

THE

PONDWEEDS

Several

species of Pondweed may be found by the enthusiastic botanist in the

Highland Lochs, pools, and in the slower streams. Of these a number of

species are completely submerged and will be dealt with here, but the

species with floating leaves will be described later on.

Three of

the species have broad, pellucid leaves and form dense masses in the

water, whilst the other two have very fine, narrow leave.

Of the

former we have a fine species in the Shining Pondweed (potamogeton

lucens) which inhabits fairly deep, still water, and is more likely to

be found in lochs or in deep pools in rivers. It is found in

Inverness-shire and most the Highlands to the southward, as well as in

Skye and Sutherland.

Its stout

stems may be as much as six feet in length, whilst the oblong, wavy,

brown, pellucid leaves with several green veins may be as much as ten

inches in length. In clear water, the leaves may be found almost to the

base of the plant, but in turbid water only the upper leaves are fully

developed.

The stems

lengthen until the surface of the water is almost reached. In the axils

of the upper leaves, and carefully wrapped up in the transparent stipules,

we shall find the flower buds. In summer the stout flower stalks elongate

and burst through their membranous cover to rise above the water where the

thick cylindrical spike of flowers betrays the presence of the plant. The

greenish flowers contain no nectar and are wind pollinated, and thus we

see that in spite of its high specialization to aquatic conditions, the

plant is still dependent on the open air for the perpetuation of the race.

Another

fine species, which I found in great luxuriance in a small pond near the

boat-of-Garten, in Speyside, is the Long-stalked Pondweed (P.

praelongus), which has a similar distribution to P. lucens. It

has stout, whitish stems clothed with oblong, sheathing leavs, which are

three or four inches in length and rather concave in form. They have a

similar texture to those of P. lucens, and their shiny brown

surface makes one think of some marine seaweeds. The flowers are produced

in large, dense spikes on long thick stalks.

A common

and well distributed species to be found throughout the Highlands is the

Perfoliate Pondweed (P. perfoliatus). It resembles the foregoing,

but is rather smaller in all its parts. The oval leaves, which completely

embrace the stem, are very thin and transparent and are beautiful objects

when seen under the water. The dense spike of flowers is produced on a

stout, short stalk.

The

fine-leaved species are to be found in most parts of the Highlands and

inhabit streams as well as still waters. The Small Pondweed (P.

pusillus) forms a tangled mass of fine, thread-like stems and narrow,

linear leaves of a dull, olive-green colour. It does not form a rhizome

and the plants float freely in the water, or are attached by adventitious

roots given off from stems. The small spikes only just appear above the

surface.

During

the summer the stems produce green, bud-like objects, which drop to the

bottom in the autumn when the stems and leaves die down. The following

spring, they sprout and give rise to new stems, leaves and roots. The

production of such winter buds is common among aquatics, the advantage to

the plant being that the buds pass the winter at the bottom of the water

where freezing is rare.

A further

species, P. filiformis, is a rather similar plant, but the leaves

are almost hair-like, and it perennates by means of structures called

turions. The two lower internodes of each leafy shoot swell up and become

stocked with starch, and in the autumn, when the stems die down, these

tubers fall to the bottom of the pond to recommence the species the

following year.

Pipewort (Eriocaulon heptangular)

This

remarkable plant is the only European representative of the American

family Eriocaulceae, and its only stations in Europe are in

Connemara, in western Ireland, and at two places in Scotland, viz., Iona

and Dunvegan, Skye. The plant is almost certainly native in these areas

and was discovered as long ago as 1764.

The

Pipewort Family is mainly tropical, but several species are found in North

America. How our present plant crossed the Atlantic to Scotland and

Ireland is a mystery. It will be noticed, however, that it only occurs in

areas in close proximity to the Atlantic. Now very often seeds of plants

inhabiting the islands of the Caribbean Sea and the surrounding shores are

washed up on the western coasts of Britain by the North Atlantic Drift.

Sometimes they germinate, but they rarely establish themselves in our

climate; this does not, however, preclude the chance of the survival of

adaptable species. Once the seeds arrive on our shores, it would be

fairly easy for sea-birds to transport the seeds upon their feet from the

seashore to neighboring lakes. The element of chance involved would

explain to neighboring lakes. The element of chance involved would

explain the scattered distribution of the plant.

The

Pipewort is not the only American plant to be found wild in Britain, about

six species being listed. The best known are the Blue-eyed Grass (Sisyrinchium

angustifolium), a member of the Iris Family, and the Orchid, the Irish

Lady’s Tresses (Spiranthes Romanzoffiana). In view of the preceding

facts it will be seen that the Pipewort is a very interesting plant.

Like many

aquatic plants, it has a slender rhizome creeping in the mud at the bottom

of the lake, the branches having a pipe-like appearance as they consist of

long, white, cylindrical sections. One the plant is established, it soon

forms large colonies by means of this quick growing, spreading rhizome.

From the

nodes arise several very narrow leaves, which have the pellucid, soft

texture, that we have noticed as characteristic of the underwater leaves

of the Pondweeds, although, of course, the Pipewort is not related to

them.

From the

middle of the tuft of radical leaves arises the leafless, erect, flowering

stem which may attain as much as two feet in height, and has a six-to

eight-angled structure. At its summit is produced a dense head of

flowers, which when young is protected by a long sheath, but on growing

the stem pushes the flower head out of this sheath.

The

flower heads are composed of many tiny flowers, the central ones bearing

stamens only, whilst the outer ones have pistils only. The flowers are

intermixed with tiny chaffy bracts, the outer of which are large and form

an involucre which protects the immature flowers before the head opens

out.

Each

flower consists of four perianth segments, the outer two of which are

black in colour and fringed at the summit, whilst the inner two are lead-colored

with a black spot at the base. In the males the two inner segments are

united to form a cup-like perianth containing the four stamens. The

females contain a rounded two-chambered ovary, surmounted by two stigmas.

The

flowers are obviously adapted to insect pollination and are in fact

visited by flies who come in search of nectar, and on being disappointed

content themselves with the pollen of the central flowers. They usually

alight on the outer female flowers and then cross into the males flowers,

so that any transported pollen will be left on the female flowers and

cross-pollination effected.

Shoreweed (Littorella uniflora)

This is

one of the commonest and most widely distributed of the plants which

prefer the lochs and tarns for their habitat. It is to be found

throughout the whole area of the Highlands and climbs the mountains to

2,000 feet.

The

plant, which inhabits the shallow shore waters, is usually totally

submerged, the possesses a short, perennial stock from the summit of which

arise several fleshy, narrow leaves, which are usually two or three inches

in length. They possess no stomata and respire like other submerged

plants, but if the level of the lake recedes and the plant is partially

exposed, the aerial leaves then produce stomata so that respiration and

assimilation can continue.

The stock

gives rise to runners so that in time the plants form mats of leaves and

stems beneath the surface. These colonies are so dense that other plants

are unable to penetrate them, hence competition is mainly between plants

of the same species.

The

flowers are of two sorts. The males are produced on erect, leafless

peduncles, which are each terminated by one or rarely by two flowers,

consisting of four narrow, green sepals and a four-lobed, greenish-white,

tubular corolla. The four stamens are the most conspicuous part of the

flower and possess very long filaments terminated by large, oval, yellow

anthers.

The

females are stalkless and must be carefully searched for among the bases

of the leaves. They consist of four narrow, green sepals surrounding a

greenish, pear-shaped corolla which is closely applied to the ovary. The

flower is remarkable for its long, stiff, erect style, and as it often

happens that the lower part of the plant is in water, the need of such a

long style becomes apparent. The flowers produce no nectar and are

adapted to wind-pollination.

One must

not think, however, that one has only to visit the lake shore during the

flowering season to find the flowers of the Shorewood. Usually it remains

submerged and then it does not flower at all, the leaves becoming long and

grass-like and the plant depending on vegetative reproduction by means of

runners.

Water

Awl-wort (Subularia aquatica)

This is

an interesting little plant which may be found in some of the higher

Scottish lakes and tarns. I have found it in bleak, wind-swept Loch

Etchachan, near the summit of Ben MacDhui, in that wildest of all lakes

Loch Avon and in many of the small tarns in the Lochaber Mountains.

When one

first approaches the shores of Loch Avon, one is astonished by its

completely barren, desert-like aspect. Only here and there a patch of

green shows that vegetation does exist, but in the main the scene is one

of sublime grandeur, of precipitous cliffs and boulder-strewn shores. If

we look closer, however, and the season in summer, we may notice a soft

green carpet on the gravelly lake bottom. This is the lowly Water Awl-wort,

often the only plant to be seen, but in certain places the Water Lobelia

bears it company.

It is

remarkable among the mountain plants in being an annual, the seeds

commencing to germinate as soon as the temperature of the water begins to

rise in the spring, and this may not be before June in the higher lochs

which often have a covering of ice in early May.

The whole

plant is rarely over three inches in height and in the higher lochs, where

the growing period is short, only one or two inches, the very short stem

giving rise to a tuft of fine roots which anchor the plant in the gravelly

soil.

The

leaves are all radical and almost cylindrical in form, very slender and

pointed, and are completely glabrous, rarely rising above the surface of

the water.

From the

midst of the leaves arises a short, naked stalk or scape which may

protrude through the surface into the air, but if the water is deep it

remains below the surface. The stalk gives rise to a raceme of small

white flowers, the petals of which are very minute. When the flowers are

produced above the surface they may be visited by small insects, but as

they are very inconspicuous they are usually self-fertilized. When the

flowers are unable to reach the surface they perfect themselves under

water and do not open.

The whole

flowering period is very short, probably not more than ten to twelve

weeks, and during that time the seed must germinate, the leaves are

produced, the flowers are pollinated and the seeds set and distributed, so

that it is not astonishing that the plant is so small

AQUATICS WITH FLOATING LEAVES

This

section of aquatics contains some of our most beautiful native flowers and

also some very interesting species.

In our

Highland lochs we can find the beautiful and chaste White Water Lily,

surely the queen of British flowers; its lovely golden cousin the Yellow

Water Lily; the Water Crowfoots, of which many varieties abound; the less

interesting Bur-reeds and the very common Floating Pondweed.

The

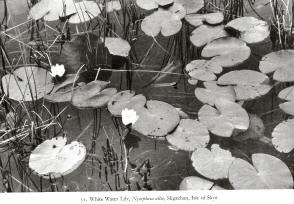

White Water Lily (Nymphaea alba) The

White Water Lily (Nymphaea alba)

Far away

in the depths of the western Highlands, where from the hilltops one can

see the inspiring outlines of the Black Coolins against the setting sun,

where Rum and Eigg float like galleons on the shimmering Atlantic, there

lies, in a peaceful glen, a beautiful tarn, whose mirror-like face

reflects back the purple-mantled mountains and the black pines that fringe

its further banks.

Here,

where all is peace and not intruding footsteps break the silence, Nature

has had the happy thought to adorn the placid waters with the queenly

flowers of the White Water Lily.

Here one

will find hundreds of great, pure white blossoms floating on the silver

loch like fairy ships. Here one can study these beautiful treasures amid

scenes untrammeled by man, as the soft south-west wind with its elusive

tang of the sea gently ruffles the large, round leaves, breaking up the

mirror-like surface of the water into a million scintillating wavelets.

I have

often admired the White Water Lily since then, but never under conditions

where Nature dwelt in such exquisite surroundings.

It is one

of the loveliest members of a very beautiful family of which many,

including those with flowers of brilliant blues, reds and yellows are

cultivated in our ornamental gardens and greenhouses. The gigantic

Victoria regia of South America and the sacred Lotus belong to this

same delightful family.

The Water

Lily is a perennial plant with a very thick, fleshy rootstock which is

usually buried in the soil at the bottom of the lake. If we examine this

rootstock in the springtime, we shall find that near one end there is a

large green bud, which is the commencement of the Water Lily plant. The

rootstock will be found to be marked at regular intervals with a scar,

marking the position of the leaves and flower stalks of other years. Each

year the rootstock lengthens, the new portion of the present year giving

rise to the new plant next year.

As the

days length and become warmer, the bud swells and gives rise to several,

thick, rubber-like stems surmounted by the leaves which at this stage are

curled up tight. The stems continue to grow until they attain the surface

of the water, where the leaves open and lie flat. At the same time the

flower stem, which was contained among the leaf stalks, reaches the

surface, the flower at this time being enclosed in a spherical bud and

protected by the smooth, thick, outer sepals.

If we cut

across one of the stems, we should find that four tubes run along the

whole length of them. These tubes are hollow and filled with air which

helps to keep the stems buoyant, so that they can support the large leaves

and flowers, as well as resist currents.

Each leaf

is very large, often six to eight inches in diameter, and is almost round

except for one side which is deeply heart-shaped. The stem is situated in

the middle of the under surface instead of at the base as in most plants.

Each leaf lies flat upon the surface of the water, and as the lower

surface is in constant contact with the water, no stomata are situated

upon it. It is usually reddish in colour below, but of a bright green

above and very smooth and highly polished. This is an important feature

as any water which may splash upon the supper surface (and this may happen

frequently on a windy day) immediately runs off the smooth surface, and

does not lie upon t and choke the stomata.

The

flowers commence to open in June and float upon the surface. They are

very large, often as much as four inches in diameter and the petals are

dazzlingly white, sometimes fading into rose-pink at the base, and are

scentless. This is a reverse of what one would expect, as in the plant

world most white flowers are highly perfumed and open in the evening when

their scent attracts night-flying insects. The Water Lily, however, open

during the day, closing in the early evening, and as its blooms are very

conspicuous, it has no need of perfume to attract day-flying insects.

If we

examine a flower carefully, we shall find that it has four large green

sepals, which protect the flower whilst in bud and also at night and in

wet weather, when the flower is closed.

Within

the sepals, we shall find several rows of pure white petals which are

glossy and of a fleshy texture. The petals pass gradually into the many

rows of stamens, in which the outer stamens have petal-like filaments

surmounted by sort anthers, and the inner ones have fine filaments

surmounted by long anthers.

In the

centre of the flower are situated the many carpels which are imbedded in

the fleshy receptacle and radiate from the common centre. Each cell is

surmounted by short anthers, and the inner ones have fine filaments

surmounted by long anthers.

In the

centre of the flower are situated the many carpels which are imbedded in

the fleshy receptacle and radiate from the common centre. Each cell is

surmounted by the stigmas which form a ring around the receptacle.

These

flowers are visited by a host of insects, bees, flies and beetles being

the chief benefactors, but many other insects also visit this beautiful

flower for pollen and the nectar which is secreted at the base of the

petal-like stamens.

After the

flowers have been pollinated they close and the stems gradually fill with

water, the weight of which drags the flower down to the bottom of the

pond, where the flower decays and the seeds are released to float along

the bottom until they come to rest on the mud to give rise to new plants.

Probably

no sight in these islands is lovelier than that of a loch or tarn covered

with the great green leaves and glorious flowers of this exquisite plant.

Happily, the White Water Lily is by no means rare, and one can find many

loch and tarns in the Highlands covered by its delightful blooms.

Yellow

Water Lily (Nuphar lutea)

This

plant is very common in lochs and tarns all over the Highland area, and in

many lochs in the Hebrides. It is very handsome and, although lacking the

chaste beauty of its white cousin, it can hold its own with most of our

commoner plants.

Its

large, cordate leaves spread out flat upon the surface of the water and,

as they are highly polished, any water splashing upon them rolls off.

The

flowers, which are produced several inches above the surface and are

bright yellow in colour, are cup-shaped in form and have five or six

large, fleshy, concave sepals which are greenish on the outer surface, and

are the advertising agents of the flower.

The outer

of the twelve to fifteen petals, which are arranged in whorls around the

ovary, are rounded, resembling the petals of normal flowers, but the inner

ones are small and oblong in form passing gradually into the stamens.

The

stamens and ovary are very similar to those of the White Water Lily.

The

flowers, which smell rather strongly, attract hosts of flies, bees and

butterflies, and are pollinated as in the case of the preceding.

In

certain Highland lochs we have yet another water lily, the Least Yellow

Water Lily (N. pumila). This plant is much smaller in all its

parts, and the stigma has only eight to ten rays compared to fourteen to

twenty in the case of the larger plant.

Least

Bur-reed (Sparganium minimum)

This

species is a close relative of the Branched Bur-reed (S. erectum),

a common plant around the marshy edges of the lochs and streams (see

later).

The stems

are very weak and are rooted in the mud at the bottom of the loch, and as

they ascend to the surface of the water, the deeper the loch the longer

are stems. From their upper part long, floating, grass-like leaves are

given off. The wind-pollinated flowers are produced on aerial stalks, and

are arranged in spherical heads, the upper ones consisting entirely of

male flowers, the lower two or three being female.

Another

floating Bur-reed (S. natans), which may be found rarely in deeper

waters, is very similar to the preceding, but is large n all its parts and

appears to be a variety of the Branched Bur-reed.

Bladderwort (Utricularia)

I have

dealt in an earlier chapter with the Insectivorous plants inhabiting the

bogs. The present subject is another member of this interesting group of

plants, but it prefers lochs, ponds, ditches and marshy pools for its

habitat.

The

Bladderwort is divided into four species, three of which may be found in

the Highlands, usually at fairly low altitudes. They are the Common

Bladderwort (U. bulgaris); the Lesser Bladderwort (U. minor)

and the Intermediate Bladderwort (U. intermedia).

A study

of these fascinating plants will fill us with astonishment. Their amazing

way of life and the intricacy of the mechanism which enable them to lead

it, are not equaled anywhere else in the plant world.

If we

take a plant of the Common Bladderwort out of water, we shall find that no

roots attach it to the bottom of the pond and that it is free-floating in

the water.

It is

composed of an intricate mass of slender green branches, which give rise

to many bright green leaves, consisting of many finely-cut segments. If a

leaf segment is examined under the microscope, it will be seen to be

covered with short, tiny, pointed hairs.

Let us

carefully examine the leaves. We shall see that they are clothed by

several bladder-like structures which are rounded in form and are hollow

within. To the early botanist these represented air-sacs by which the

plant was supported in the water. Their actual function is much amazing

than that as they are actually very efficient traps with a very delicate

mechanism.

They are

produced upon short stalks which arise from the main leaf branches. The

entrance to the vesicle is a tiny rounded portal, surrounded by fine,

branching hairs which stand upright around its edge.

What is

the function of this strange structure? A very instructive experiment can

be arranged as follows. A leaf with two or three vesicles attached is

placed in a watch-glass containing a few drops of pond water. This water

will probably contain many minute organism call Water Fleas (Daphnieae).

Now focus the microscope upon a bladder and watch the entrance carefully.

If we are lucky we shall see one of these tiny water fleas approach the

entrance to the vesicle. Attracted, perhaps, by it bright green interior,

it tries to enter and in so doing will touch the fine hairs, and these

immediately drive the water flea into the bladder. At the same time a

valve in the entrance shuts like a spring trap effectually imprisoning the

little animal.

The water

flea can be seen swimming around in the bladder, but gradually its

movements become slower until it stops and in an hour or two it will be

seen to be dead.

What is

the object of this seemingly wanton destruction? Obviously the plant is

not activated by the pleasure of the hunt or by any wish to destroy. We

can find the answer to this question by carefully opening a vesicle along

its long axis and placing it, with the inner surface uppermost, under the

microscope. The walls of the inner surface will then be seen to be

covered by four or five branched, star-like hairs, the absorbing organs

whose function is to absorb the products of decay given off by the

decomposing water flea.

Thus we

see that the Bladderwort catches these water organisms in order to

supplement its food supply. As we have seen, the plant produces no roots

and hence cannot obtain salts, such as nitrates, from the soil, but the

decaying water fleas supply nitrogen salts to the plant and hence makes up

for this deficiency.

In the

state of Nature little organisms are always being chased by larger ones,

and often enter the bladders, thinking to find refuge within their bright

green walls.

In summer

the submerged plant gives rise to stout scape about six to twelve inches

high. It is naked except for a few small scales at the base and gives

rise to a raceme of four to eight conspicuous, pale yellow flowers.

The calyx

consists of two ovate, green, similar sepals, one being produced upwards

and other one downwards.

The

corolla s bright yellow or even orange in colour and two-lipped, having a

close resemblance to that of the Antirrhinum. The lower lip is very

swollen and concave with a prominent palate, the lips being inclined at an

angle of forty-five degrees to make a landing stage for bees, and it is

produced backwards as a short, conical spur in which the nectarines are

hidden.

The upper

lip is much smaller, half erect and three-lobed and meets the lower lip,

the corolla being almost closed.

The ovary

is a globular structure situated at the base of the corolla and is

surmounted by a single style with a bi-lobed stigma situated in the roof

of the mouth-like flower. The two stamens are adnate with the corolla,

the two anthers being situated in the roof behind the stigma.

When a

bee alights upon the lower petal, it pushed it proboscis between the lips

of the corolla and, on its way down to the spur, it will tough the stigma

which immediately folds up. Beyond this the proboscis is dusted with

pollen by the anthers. On withdrawing the pollen will not tough the

stigma, as it has moved out the way, thus avoiding self-fertilization.

After

fertilization the ovary forms a rounded capsule containing many small

seeds.

The plant

does not depend on seeds alone for the continuation of the species, for in

autumn the stems form large buds, which drop off and remain dormant at the

bottom of the pond during the long winter, opening in spring to form new

plants. At this time the bladders are full of water and anchor the plant,

but as the flowering season approaches the bladders fill with air and the

plant becomes buoyant, thus being able to produce its flowers above the

surface.

The Less

Bladderwort differs in being smaller in all its parts and with only one or

two bladders to each leaf.

The

Intermediate Bladderwort is rather different as the bladders are not borne

on the leaves, but instead are produced on colorless shoots buried in the

mud. The nature of these shoots is rather obscure as they are geotropic,

i.e. they grown down into the ground n the same way is roots, but they do

not have a root structure. The flowers are bright yellow and nearly as

large as those of the Common Bladderwort. This species is rather rare and

local in its distribution.

Water

Crowfoot (Ranunculus aquatilis)

One of

the commonest and most widely distributed of all aquatic plants is the

lovely little Water Crowfoot which we can be fairly sure of finding in

running streams, in quiet lochs, in stagnant pools and on damp mud.

It

assumes many different forms in relation to the varied conditions under

which it lives, and hence has been divided into many sub-species and

varieties.

I will

commence my description of this interesting group of plants with the

species found in running water. There are two or three supposed varieties

of this type, included under the name Ranunculus fluitans.

In this

plant all the leaves are submerged beneath the water. It is firmly rooted

at the bottom of the stream and sends up fairly stout stems, which take up

a position parallel to the current, where they offer the least resistance

to its passage. The leaves are large and cut up into very fine, hair-like

segments which also lie parallel to the current, and are an adaptation to

havitat as the current would cut a large entire leaf into ribbons.

From the

axis of the leaves fairly stout peduncles rise above the surface of the

water. The flowers are the only aerial portion of the plant, and the

stout peduncles are well able to resist the force of the current and keep

the flowers upright in the air.

The

flowers are pure white in colour and larger than in most varieties of

Water Crowfoot. This is probably in order to make them more conspicuous,

as smaller flowers would hardly be seen against a background of running,

shimmering water.

The

flower, which possesses a green calyx of five spreading sepals and a

corolla of five white obovate petals with a yellow patch at the base of

each where the nectar is situated, are visited by the smaller bees and

flies, and are pollinated in a similar way to those of the Buttercup (see

Chapter XIX).

After

fertilization the peduncles bend downwards and the seeds are released in

the water, which distributes them far from the parent plant. It thus

colonizes large areas and may form a mass of vegetation in the centre of

the stream, thus slowing the current and causing the deposition of silt.

In the

quiet waters around the edges of lochs and ponds, we may meet with several

other varieties of Water Crowfoot, which all agree in having much divided

submerged leaves. These dissected leaves spread out like a fan in the

still waters and carry on photosynthesis in the same way the leaves of the

completely submerged aquatics, e.g. Myriophyllum.

The

stems, however, are supported by the floating leaves, which also carry on

photosynthesis. The leaves are rounded in form and divided into three to

five wedge-shaped segments, or may have five quite rounded segments.

In some

types, including R. circinatus, the submerged leaves spread out

around the stem and on being taken out of the water they do not collapse

as in R. fluitans, but remain rigid. In other types there are also

floating leaves and here are included R. peltatus and R.

heterophyllus. They form dense colonies, as their floating leaves

obstruct the light from entering the water, they make if difficult for

other plants to thrive in their territory. In winter they sink to the

bottom of the loch and are safe from frost and ice.

Along the

muddy fringes of lochs, ponds, or streams, we may find more types of this

ubiquitous plant. They are the Mud Crowfoot (R. Lenormandi) and

the Ivy-leaved Crowfoot (R. hederaceus).

They are

both creeping plants whose weak stems give off adventitious roots at the

nodes, and branch in all directions with the result that one plant may

cover quite a large area.

The

leaves, which are on short, erect stalks and are kidney-shaped, with five

rounded segments, are smooth, shiny and bright green in colour, and in

shallow water they float upon the surface.

The

flowers are only half-an-inch across in the case of the Mud Crowfoot,

whilst in the Ivy-leaved Crowfoot the petals are hardly larger than the

sepals. In these plant the flowers are seldom visited by insects, and

hence they depend on self-fertilization to obtain seed.

Another

variety, R. trichophyllous, often to be found upon mud, is an amphibious

type and can live either submerged or exposed, its leaves being cut into

fine segments, whilst the stems are short and tufted. The flowers are

very small and pinkish in colour, and are usually self-fertilized.

A study

of these plants will give us a good idea of the role played by environment

in forming the structure of plants.

There is

no doubt that all the above plants arose from the same ancestors, but

owing to very different conditions of life the various types are evolving

away from the parent type to become more and more specialized to a certain

type of habitat. Thus R. fluitans could not compete with a still

water type and vice-versa.

Another

aquatic Ranunculus that may be found in wet places, on the edges of lakes

and streams, is the Lesser Spearwort (R. Flammula). It possesses

long, lanceolate or ovate leaves which are produced above the surface of

the water. The flowers are yellow and born upon fairly stout peduncles,

and are very similar to those of the Buttercup, but are smaller. This

plant has also evolved several varieties, one of which, R. scoticus,

grows under water n a few lakes in north-west Scotland, its leaves being

reduced to awl-like petioles. Another variety, R. reptans, a

slender, creeping plant with linear leaves, may sometimes be found in

Scotland.

FLOATING PONDWEEDS

We have

already dealt with the submerged Pondweeds in the preceding section of

this chapter, and we are now concerned with the type which has floating as

well as submerged leaves. The typical example, and the most widespread

and common, is the Floating Pondweed (Potamogeton natans).

This

plant is a fine example of adaptation to aquatic conditions. It has a

long, white rhizome, which creeps along the mud at the bottom of the pond,

giving off many fibrous roots which anchor it firmly. The rhizomes of

many different plants cross over each other and form a dense mass of stems

and roots which hold together the mud, leaves and other debris covering

the pond bottom.

From the

rhizome arise the long, slender, pliant, leafy stems which grow up to the

surface of the water, supported by the air which collect in the spongy

tissue of the stem. At the nodes the under-water stem often gives rise to

thin, brown, pellucid, narrow leaves which remain submerged and absorb

carbon-dioxide and oxygen from the water, and until the floating leaves

are produced, the plant is dependent on this source.

When the

stem reaches the surface, the upper leaves, which have been carefully

rolled up inside cylindrical, transparent sheaths, break out of their

prison and, supported on long stalks, they open out and float on the

surface of the water. They are leathery and elliptical in form with dark

green, polished upper surface on which the stomata are developed. The

under surface is brownish with a thick impermeable cuticle. These leaves

provide the plant with by far the greater portion of its oxygen and

carbon-dioxide.

The stems

often reach three or four feet in length, depending on the depth of the

water. Once the floating leaves are fully developed, a stout cylindrical

flowerstalk appears from a tubular sheath in the axil of one of the

floating leaves. It is terminated by a long spike of green flowers.

The

flowers consist of four tiny green perianth segments surrounding four

sessile green carpels. Opposite the join between each carpel is a

stalkless stamen.

The

absence of colour and perfume shows that the flowers do not depend on

insects for pollination, but they are in fact wind-pollinated. If we

visit a colony in summer, we shall see that the surface of the water has a

yellow tinge from the abundant pollen which has been blown from the

stamens. This gives point to the fact that wind-pollination is a wasteful

way of obtaining fertilization, as enormous quantities of pollen never

reach the pistils of other spikes.

A similar

species, P. heterophyllus, is also a common and well distributed

plant, but it prefers the more acid types of lochs and pools. The

floating leaves are much smaller, being only one or two inches in length,

whilst the submerged leaves are very long and narrow with a few parallel

veins. Sometimes no floating leaves are formed and it is then

distinguished with difficulty from submerged leaved species.

P. alpines is closely related to P. lucens

(see page 221), but it has shortly-stalked, reddish, floating leaves

which in shallow water may even become erect. In deep water narrow,

stalkless, submerged leaves are also formed. This species is found in

most of the Highland area south of the Caledonian Canal and in the South

Hebrides. |