|

The

marshes differ from the bogs by the fact that they are usually produced at

low altitudes and do not form peat. They are usually found around

low-lying lochs, especially where streams enter them, forming muddy deltas

as they run into the still waters. In other places they are found where a

loch or pond has become silted up until the water is shallow, giving marsh

plants the chance to establish themselves.

It must

be remembered that a marsh flora is only transient and is not a fixed

association of plants like that of the Pine Forest. The marsh plants are

continually adding to the soil by the decay of their leaves and stems,

whilst their stems also cause obstructions which make the water deposit

mud and sand around them. In time the upper layers dry out and the marsh

plants gradually give place to shrubs, and finally trees. We shall come

across marshes in all states of advancement in various parts of the

Highlands.

Marsh

plants have their roots and lower stems embedded in mud and water, and

therefore these parts are usually spongy in structure, with many air

passages and air spaces, which allow oxygen to pass down inside the

tissues to the buried roots, rhizomes and stems.

They

rarely possess xerophytes adaptations as they have an abundant water

supply and, as they inhabit low-lying, less windy situations than the bog

lands, they do not suffer from drying winds.

They

often form large colonies, as for example the reeds and various kinds of

sedges and grasses.

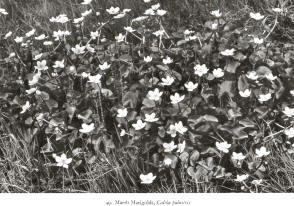

Marsh

Marigold (Caltha palustris) Marsh

Marigold (Caltha palustris)

One of

the commonest flowers of the Highlands is the Marsh Marigold, which is

found in boggy marshy places and beside rivers and streams throughout the

Highlands and well up the Highland mountains. I have discovered forms of

this plant at 2,500 feet on Braeriach in May/

Who has

not admired in spring-time the beautiful golden beds of these lovely

flowers with their large bright green leaves? Wherever we find their

golden cups, we may be sure that the soil is wet and marshy, and we must

walk warily to escape wet feet.

In the

Highlands there are least three distinct forms of the marsh marigold.

In the

lower valleys, in the ditches around the meadows, in swampy riverside

marshes and around lochs, the common species C. palustris is

abundant. In more elevated regions this species is often replaced by

C. radican, a much scarcer plant.

In the

higher regions, climbing well up the mountain sides, we have the form

C. minor, which is a small species and quite common in boggy areas.

Caltha palustris

The Marsh

Marigold is a perennial, the thick tuberous root being buried deep in the

mud, where it passes the long hard winter safe from frost and cold.

With the

return of milder conditions, a green bud forms at the tip of the rootstock

and from this arise the leaves and then the flowerstalks. The radical

leaves are on long, thick, hollow stalks and are large and kidney-shaped

with a slightly crenate border, and as they are absolutely glabrous and

very smooth, water does not lie upon them. The stems often root at the

lower nodes, are often branched, and attain a height of about one foot,

producing one or two flowers on stalks about two inches in length.

The

flowers are large, of a bright golden yellow and very conspicuous. As

this plant usually forms large colonies, the conspicuousness and beauty of

the flowers are greatly enhanced.

The

flowers of the Marsh Marigold are peculiar in that they possess no petals,

the sepals taking their place. Within the bright, golden, glossy cup, we

find that the centre of the flower occupied by a green cone which consists

of five to ten carpels. Around the central core are arranged the many

stamens whose anthers open outwards toward the sepals.

Nectar is

secreted on the sides of the carpels and an insect naturally alight on the

centre of the flower where it must leave imported pollen upon the carpels.

As it turns round to obtain the nectar secreted around the cone, it

becomes dusted with pollen, which it will transfer to the next flower it

visits, thus effecting cross-pollination.

Many

insects visit the flower--honey-bees, bumble-bees, mining bees, flies and

Syrphidae being the chief visitors attracted by the beautiful

blooms.

Caltha radicans

In this

species the plant is much more slightly built, with much more fragile

stems. The radical leaves, which are on very long stalks, are

heart-shaped and have an acutely toothed edge, whilst the upper leaves are

small and kidney-shaped. The flowers, which are quite small, are usually

solitary and terminate a long stalk. They are much less conspicuous than

those of C. palustris, which may account for its comparative

rarity.

With

flowers, as with the business man, a advertisement if the key to success.

Caltha minor

This

species, which is probably a mountain variety of C. palustris,

varies greatly in size in relation to elevation and the exposure of its

habitat.

It often

approaches Caltha palustris although it is never so luxuriant, the

stems being shorter and less thick, while the leaves are much smaller.

The flowers are produced on long stalks and are solitary, being slightly

smaller than in the common species. This type is common in the upper

glens and I picked several fine specimens in a bog close to the Fairy Loch

in the Pass of Ryvoan at 1,200 feet.

At higher

elevations it becomes much smaller in all its parts, often being under

four inches in height with solitary small flowers.

This is

the reverse of what often occurs in mountain varieties of lowland plants

where usually the flowers are much larger and more conspicuous.

I have

found this variety at altitudes of 2,500 feet on Braeriach and at over

3,000 feet on Ben Nevis.

The

Water Avens (Geum rivale)

The Water

Avens is quite a common plant in marshy places, along streams and ditches

and in boggy meadows. We may find it in company with the Red Rattle, the

tall strangely perfumed Marsh Valerian, the beautiful hairy fringed

flowers of the Bog-Bean and the dusky red Marsh Cinquefoil.

I first

became acquainted with it near the head of the beautiful Glen Nevis, where

it was growing in a marshy patch at the bottom of the deep, boulder-strewn

gorge of the Nevis, and whenever I review my specimens this romantic spot

comes back to me with its black precipices, its huge rough boulders, its

swirling waters and its beauty and peace. Its rocky sides are a perfect

rock garden with Yellow Saxifrage, Wood Geranium, Melancholy Thistle,

Rose-root and the Butterwort watered by the little streams that tumble

down from the high summit of Aonach Mor.

The Water

Avens is a member of the Rose Family and closely related to the Common

Wood Avens, so common in the Lowlands.

It

possesses a perennial rootstock which usually creeps for a short distance

in the muddy soil, where it makes its home. The rootstock is crowned by a

rosette of radical leaves which are long-stalked and pinnate. They

consist of one large, rounded, terminal segment which may sometimes be

divided into three, with several much smaller leaflets further down the

main mid-rib. They are covered on both surfaces with fairly long hairs,

which prevent moisture being deposited upon the surfaces and clogging the

stomata. This rosette sends up simple, unbranched stems to a height of

one or even two feet in luxuriant specimens, and they are also clothed in

pinnate leaves.

At the

termination of the stems solitary flowers are formed on long peduncles,

which are curved, with the result that the flower is in a drooping

position.

The

flower is a rather interesting structure possessing a double calyx

consisting of five sepals surrounded by another calyx of five sepals known

as the epicalyx, the sepals of which are placed in the spaces between the

sepals of the inner calyx. The whole structure is hairy and forms an

admirable protection to the flower whilst in bud, and also acts as a

barrier to creeping insects, which would try to steal pollen and nectar.

The five petals are semi-erect and of a deep purple colour shaded to

orange.

The

flowers secrete abundant nectar like many other marsh plants do, water

being a prime factor in the manufacture of this sweet substance. They are

visited by many insects, especially bees. The erect position of the

petals makes it necessary for these insects to alight in the middle of the

flower, where they must leave imported pollen upon the hairy carpels. As

the stigmas mature before the stamens it is impossible for

self-fertilization to take place.

After

flowering each carpel produces a long awn which, after it has reached a

certain length, develops a kink and then continues to grow. In a little

while the piece beyond the kink breaks off and leaves the carpel with a

long hooked awn. What is the reason for this hook? Well, it is a means

to ensure the distribution of the species.

As we

have already seen, plants try to distribute their seeds as far away from

themselves as possible. Thus there will be no competition between the

parent and its offspring and the species will be distributed further and

further from its place of origin.

To arrive

at this end, plants have adopted many ingenious devices whereby the seed

is transported for long distances. As we have seen the Wood Geranium

throws its seeds a considerable distance by the recoil of sections of the

capsule; the Hawkweeds, Dandelion ad many other Composites as well as

Willow-herbs, Willows, etc, are fitted with parachute-like hairs by which

they float away on the wind; others, such as the Primrose, having very

light seeds which are blown considerable distances by windy gusts; others,

as the Wild Rose, Whortleberry, etc., enclose the seeds in a succulent

envelope which is devoured by birds, the seeds being dropped far from the

parent.

But the

Water Avens has so adapted its seeds that they may take ride upon the back

or sides of any passing animal.

The

hooked awn catches into the wool of sheep, or the hairy coats of cows,

horses, etc., or perhaps in the clothing of a passer-by, and drags the

rest of the seed in its hairy coat with it. The animal moves on with its

tiny voyagers who gradually drop off one by one. Some perhaps fall on dry

ground and do not germinate, but others will fall in wet places and give

rise to new clumps of Water Avens.

So does

the study of plant life illustrate how amazingly Nature obtains her ends.

For had the seeds dropped down to earth around the parent plant they would

have been suffocated and would have died for want of living space, but

being carried far away they have a much better chance of survival.

Meadow

Sweet (Spiraea Ulmaria)

Another

common plant of the marsh lands, riversides, lochsides and ditches is the

Meadow Sweet, or as it is often known, the Queen of the Meadow. Like the

Water Avens, itelongs to the Rose Family, although at first sight one

would hardly associate its small clustered blooms with that family.

The

Meadow Sweet is a large plant with deep-striking perennial roots which

push down into the muddy soil, and tall, strong, flowering stems which may

attain a height of as much as three feet, and are usually of a reddish

hue. The stems and rootstock are covered with large pinnate leaves

consisting of from five to nine leaflets which are deeply toothed on the

edges. These leaflets are smooth and green above, but the under surface is

covered with a thick, white, felt-like down. This down is a common

feature of marsh land plants, its purpose being to protect them against

condensed moisture which would otherwise clog the stomata.

The

flowers, which are very small, are arranged in very dense clusters at the

termination of the flowering stems, and are cream colored and very sweetly

perfumed.

Here we

have a case of flowers being conspicuous, not because of their

individually large size or striking colours, but because of the grouping

of great numbers of small flowers to form a very conspicuous cluster of

blooms, and as if that were not enough, and to make even more sure of

visitors, these flowers are endowed with a very sweet perfume. The Meadow

Sweet blooms in mid-summer when competition is at its peak and only those

plants which show the greatest executive ability can hope to attract

insects.

The

little flowers are each formed like a small rose, with many stamens around

a central disc which contains the few carpels, and around which the nectar

is secreted.

The

stigmas mature before the stamens so that imported pollen will be left

upon them before their own stamens mature. The stigmas continue to be

receptive after the stamens have reached maturity so that in dull weather,

when few insects are abroad, self-fertilization will take place, this

being better than failure to set any fertilized seed at all.

Small

bees and flies arrive to sup at the nectar so liberally presented to them,

whilst beetles and pollen-seeking bees arrive for the pollen so easily

obtained from the myriad flowers.

THE

MARSH COMPOSITES

A very

conspicuous and imposing member of the Marsh Flora is the Marsh Thistle (Carduus

palustris). It is a plant of the less moist marshes and is not found

in standing water, although its roots dig deep into the mud and water

below the surface of the soil It attains a greater height than any other

British thistle and nine to ten feet is not unusual for it.

It

belongs to that section of plants known as biennials, i.e. it only flowers

in the second year of its existence and then dies down.

In the

first year it forms a fine rosette of large, narrow, fiercely spinous

leaves, deep green above and possessing a few scattered hairs on both

surfaces. During this period the leaves are actively engaged in

manufacturing starch, which is stored up in a large, fleshy, tap-root.

The spines prevent the leaves being eaten by animals.

The

rosettes pass the winter safety as they offer little exposure to the wind,

can support the weight of snow and, being of a tough consistency, are not

damaged by frost.

In the

spring a tall stem arises from the midst of the radical leaves, and

nourished by the abundant starch contained in the tap-root, it rapidly

increases in height.

Leaves

are produced upon the stem and their margins runs some distance down the

stem as a line of stiff, sharply-pointed spines. The leaves themselves

are narrower than the radical ones, but are also very spiny, and thus the

whole plant is well armed against the attacks of animals.

The stem

supports a large and heavy inflorescence and is particularly strong.

Besides its outwardly stout appearance, we should find that it is hollow

within and as a tub is a very strong structure, the stems are well able to

resist strong winds.

The

flower heads are numerous and arranged in several clusters in an irregular

corymbs at the summit of the stem. They are rather small and egg-shaped

and are surrounded by an involucre of many prickly pointed bracts, often

with spider web-like hairs intermingled with them. Their function is to

stop creeping insects, such as ants, reaching the flowers.

The

flowers are purple-red in colour, but plants with pure white flowers may

be found. They contain both stamens and pistils and are pollinated in a

similar fashion to those of the Spear Thistle (see Chapter XX)

After

fertilization the flower heads are transformed into a mass of silky down,

as the pappus of the seeds lengthens. When ripe they are borne away on

the wind to recommence the life cycle if they fall on suitable ground, and

as the stems are so high the seeds get a good send off.

From what

has been said it must be obvious that the Marsh Thistle is well adapted to

the life struggle and it is not surprising that it is a very abundant

plant.

Another

very common, plant in marshy and wet places is the Marsh Ragwort (Senecio

aquaticus), which is closely related to the Common Ragwort (see

Chapter XXI).

It is a

more slender plant than the latter, and the radical leaves are undivided,

whilst the yellow flowers are in the much less dense corymbs.

It is a

perennial, but very often behaves as a biennial, this seeming to depend

largely on the suitability of its habitat, good conditions being conducive

to a longer span of life.

The Marsh

Hawk’s-beard (Crepis paludosa) is quite a common plant in the

marshy land over much of the Highland area, but is more particularly a

shade plant, and hence prefers shady marshes such as occur where streams

and springs are found in the woodlands or in the shade of cliffs and steep

hillsides.

The young

plants consist of a rosette of large, ovate, coarsely-toothed leaves which

are deep green in colour and quite devoid of hairs. The rosettes are

rooted in the soft soil by a large, white, fleshy tap-root containing a

white acrid fluid which prevents them being eaten by animals.

In spring

a leafy stem arises from amidst the leaves to a height of about two feet.

The stem leaves are oblong and toothed and clasp the stem by two large,

pointed auricles, this last character being of value in identifying the

plant. These leaves are thin in texture and quite smooth as the Marsh

Hawk’s-beard is not troubled by lack of water.

The stem

is terminated by a corymbs of from eight to ten large, yellow, flower

heads, whose involucres consist of several rows of deep, green bracts

covered with black spreading hairs, which are often glandular and act as a

barrier to crawling insects.

The

flowers are pollinated in the same way of those of the Wall Hawkweed. (see

Chapter VII).

Marsh

Valerian (Valeriana officinalis)

This is

the only member of the Valerian Family which we shall meet with in the

Scottish Highlands. It is a handsome and rather imposing plant and is

quite common in some places, being a typical marsh plant.

It passes

the winter by means of a thick, tough, underground rhizome which is filled

with starch and gives off several runners which creep through the mud and

become erect at the extremity. They produced many fibrous roots and are

covered by small scale-like leaves.

From

their tip is produced a rosette of large and beautiful leaves consisting

of from nine to twenty-one leaflets arranged innately. Each leaflet may

be from one to three inches long, is lanceolate in form, and its margin is

coarsely toothed. The under surface is covered by scattered coarse hairs,

which save the stomata from becoming blocked with water by preventing the

formation of a water film over the surface.

The

flowering stems may attain more than four feet in height, are rarely

branched and are rather hairy at the base. They produce a few scattered

leaves resembling the radical ones, but much smaller in size.

The

flowers are arranged in large, terminal, corymbs cymes, which are very

conspicuous and of a pale pink or lilac colour. The individual flowers

are very small, the calyx being almost imperceptible as it is only a tiny

green ridge around the summit of the inferior ovary.

The

corolla consists of a narrow tubular portion, becoming funnel-shaped with

five small spreading lobes. Within the tube are a few white hairs which

prevent the entry of small creeping insects.

Only

three stamens are produced and their filaments are connected to the

corolla tube, whilst the anthers are produced well beyond the corolla

entrance.

The tiny

green ovary is surmounted by a large fine style which is, however, shorter

than the filaments of the stamens, hence the two lobed stigma does not

project as far from the corolla tube as do the anthers.

The

flowers are mainly constructed for pollination by butterflies which are

always to be seen around the dense masses of flowers. For this reason the

nectar is hidden at the base of the corolla tube, and the flowers produce

a sweet and powerful perfume.

The

anthers mature before the stigma and when they have shed their pollen, but

not before, the two lobes of the stigma spread apart and the flower is

ready to be pollinated.

Owing to

the cymose arrangement of the flowers, there is a long flowering season,

the flowers opening in succession a few every day. Thus in a single

inflorescence we may find flowers in every stage of development, hence one

insect may pollinate quite a number of blooms at a single visit.

After

flowering, a ring of hairs grows up from the summit of the ovary, in a

similar manner to that which takes place in the Composites. The hairs

from a pappus which acts as a parachute to the seed when it is blown from

its lofty perch by the autumn winds.

Marsh

Woundwort (Stachys palustris)

This

plant is abundant in marshy places and is a close relative to the Hedge

Woundwort (see Chapter XIII)

Like that

plant, it possesses a creeping rhizome giving off runners which produce

new plants. It differs in the leaves, which are oblong or lanceolate and

possess very short stalks. They are a paler green in colour and much less

hairy, whilst the odour of the plant is much less offensive.

The

spikes of flowers are much more crowded, the flowers themselves being pale

bluish-purple in colour, whilst the corolla tube is shorter in length and

the lower lip is broader and shorter than in the case of other plant.

It is

pollinated in exactly the same way, being constructed for the visits of

bees.

Ragged

Robin (Lychnis Flos-cuculi)

This

handsome plant is a close relative of the Red Campion (see Chapter XIII)

and is a characteristic plant of marshy and wet places.

It is a

perennial and, like most marsh plants, possesses a short rhizome which

gives rise to several erect flowering stems which only branch in the upper

part. They are clothed with roughish , short, stiff, downward pointing

hairs which make it difficult for ants and other creeping insects to climb

the stems. Even if they do traverse this formidable barrier, it is only

to find the upper part of the stem is covered with sticky hairs which trap

the poor unfortunates, who in spite of their struggles are doomed to a

horrible death. Thus does Nature arm her children against thieves and

robbers.

The

flowers are produced in terminal panicles and are unmistakable. They

resemble those of the Red Campion in structure, but each petal is cut into

four linear lobes, the whole effect being to give the flowers the

appearance of having been torn to shreads. The reason for the cut up

flowers is difficult to imagine, for entire petals, as in the case of the

Red Campion, would be more conspicuous.

The

flowers are scentless and are visited by butterflies, for which the

flowers are adapted.

To find

them in bloom we must visit the marshes in June as this species is in

flower only when the cuckoo is singing, hence its Latin name of

cuckoo-flower, Flos-cuculi.

Cuckoo

Flower (Cardamine pratensis)

Another

beautiful marsh plant which must be looked for early in the year s the

Cuckoo Flower, which belongs to the Cruciferous Family.

It must

be know to most people, its dainty flowers being welcomed with the same

sentiment as those of the Primrose. It is a perennial with a short, tough

roostock which often produces small tubers which are easily broken off and

form new plants.

From the

summit of the rootstock is given off a rosette of thin textured, pinnate

leaves each consisting of from seven to eleven leaflets which are rounded

in form.

The

flowering stem is erect and smooth and may attain over one foot in

height. It produces scattered pinnate leaves with narrow leaflets quit

different from those of the radical leaves. The stem is terminated by a

dense raceme of white or lilac flowers, which are often three-quarters of

an inch across.

Each

flower consists of a calyx of four green, narrow, erect sepals, two of

which have a pouch like base in which nectar is secreted.

The four

petals have long, narrow, erect claws, whilst the rounded limb spreads

outwards to make a landing stage for the bees. They are lined with dark

veins which run down towards the claw and guide the bees towards the

nectarines.

Within

the flower we should find six stamens, four of which are longer than the

other two. They form a ring around the cylindrical ovary, which is

terminated by a short style in the young flowers.

An insect

must push its proboscis down between the claws of the petals to reach the

sepal pouches and their nectar, but in so doing it must brush its face and

head against the anthers. At a latter period the style lengthens to place

the stigma beyond the anthers where it must be touched by any insect

arriving at the flower.

After

fertilization the ovary forms a slender pod about one inch in length and

containing many seeds. The pod opens by two valves and the seeds are left

upon a central partition from which they are blown by the wind.

Marsh

Arrow-grass (Triglochin palustre)

This

little grass-like plant s very common in marshy places in the Highlands.

It has a tufted rhizome which gives off slender runners forming daughter

plants and in time forming large colonies.

The

leaves are peculiar in being succulent in texture and cylindrical in form,

their bases being swollen and sheathing. From their midst arises a smooth

stem about six to twelve inches in height.

It is

terminated by a spike of inconspicuous greenish flowers, each of which is

surrounded by a perianth of six green rounded segments and possesses six

stamens on long, slender filaments.

The ovary

is a rounded structure and consists of three chambers, and is surmounted

by three feathery stigmas.

As one

can guess this flower depends on the wind for fertilization.

Bog

Stitchwort (Stellaria uliginosa)

This

small plant is distributed throughout the Highlands and is very common in

marshy places, being especially fond of the edges of rivulets and

springs. It climbs the mountains to over 3,000 feet, but at the same time

it is abundant at sea-level.

It is

remarkable in being an annual and this explains its small size. The

plants usually grow together in large tufts, each individual consisting of

an erect stem about six to ten inches in height and clothed with little,

sessile, opposite, smooth leaves.

The stem

is terminated by a slender panicle of tiny flowers, in which the calyx

consists of five very narrow, pointed sepals, which are longer than the

white petals. Within the corolla are ten stamens at the bases of which

tiny drops of nectar are secreted. The stamens mature before the pistil

and hence cross-pollination is often secured. Small flies are the chief

visitors, being attracted by the glistening drops of nectar.

Bog

Pimpernel (Anagallis tenella)

This

plant is not common, although distributed throughout the Western counties

of the Highlands and Hebrides. I have only twice encountered it during my

tramps in western Scotland. Once I found it covering the sides of a ditch

which bordered a road in the southern part of Mull. Its lovely pink

flowers starred the bright green, mossy banks and it gave me a thrill of

pleasure to find it there in such beautiful surroundings. I found it

again one bright September day, this time in the land of Lorne, but it was

too late for any flowers and only its seed capsules were to be found.

It

prefers wet, mossy places along the edges of streams and rivulets, and

wet, boggy places in meadows and moorlands often in association with the

Marsh Pennywort.

It is a

lowly plant with delicate, slender stems which creep over the mosses, and

give off fine roots at each node which help to anchor the stems and at the

same time assure its water supply. The stems are covered with tiny,

rounded, opposite leaves which add to the delicate beauty of the plant.

They bend

upwards at the tips, and from the upper leaves arise a few pale pink

flowers on fine stalks about an inch in length.

It is a

lovely sight to see a large colony of these plants covered with dozens of

dainty, bell-like flowers. This, of course, helps to make the flowers

attractive to insects as they are not perfumed.

The

flower consists of a calyx of five, very tiny, pointed lobes surrounding

the pink, campanulate corolla, which is deeply cleft into five narrow

segments. Within the corolla, and standing erect around the pistil, are

five segments. Within the corolla, and standing erect around the pistil,

are five stamens whose filaments are covered with woolly hairs. A little

nectar may be produced, but the flowers are mainly visited by small bees

and flies for the sake of the pollen.

After

fertilization the flowers fade and the ovary swells to form a many-seeded

capsule. When ripe the upper part of the capsule breaks away, like a tiny

lid, from the lower portion, leaving the seeds exposed upon the central

receptacle, and as they are very light they may be blow a considerable

distance by the wind.

MARSH

MINTS

Whilst

exploring the edges of streams and rivers and the marshy ground around

them, we may often become aware of a strong, mint-like smell, especially

if the day be warm and damp. This odour betrays the Water Mint, of which

two main species occur in the Highlands. One is called the Water Mint (Mentha

aquatice), the other the Whorled Mint (M. sativa). The latter

is a hybrid species arising from a cross between the Water Mint and the

Corn Mint (M. arvensis), which is also a frequent plant in

cultivated fields in the Highlands.

Both

species form dense colonies into which competitors penetrate with

difficulty, and the numerous runners push outwards, increasing the

territory of the colony each year.

The Water

Mint has a long, creeping stem, giving off long, branching roots into the

mud and water. The stems produce rounded scale leaves at each node. In

the summer and autumn the stems give rise to many slender runners which

rest snugly buried in the mud and dad leaves till the following spring.

The stems

rise erect at their extremities to a height of about eighteen inches, are

covered with soft hairs and produce pairs of stalked, ovate, toothed

leaves, which are also hairy. The stem is terminated by a large, close

spike of pinkish flowers.

Each

tubular flower secretes nectar at its base, the inner, lower portion being

covered with short hairs which impede the entry of creeping insects. In

the young flowers, the four stamens project beyond the corolla, where they

will be touched by any insect visitors, the stigma being at this time

hidden in the corolla. In older flowers the stamens have withered and the

style has so elongated that the stigma lobes project and occupy the

position originally held by the anthers. Bees and butterflies attracted

by the large, conspicuous heads of sweetly-smelling flowers visit them in

great numbers and much cross-fertilized seed is formed.

The

Whorled Mint is a very similar plant, but the flowers are produced in

whorls in the axils of all the upper pairs of leaves. They are also

visited by bees and butterflies, but as the plant is a hybrid, very little

fertile seed is set, the plants depending on their runners for the

continuation of the species. The plants vary greatly in character and all

types may be found grading from one parent to the other. For this reason

many sub-species have been named and several of these may be found in the

Highlands.

MARSH

SPEEDWELLS

We have

already made acquaintance with the Speedwell in other sections of this

book and here in the marsh lands we again meet three members of this

beautiful genus.

The

commonest and most outstanding species is the Brooklime (Veronica

Beccabunga). I forms large masses along the edges of rivers, streams

and rills, on low, marshy loch shores, in wet ditches and meadows.

It has

fairly thick, smooth stems which creep over the mud or even float on the

water along the stream’s edge. From the nodes bundles of fine roots are

given off to anchor the stems in the mud so that floods will not sweep the

plants away. The stems give off runners during summer and autumn, and

these pass the winter safely buried in the mud.

The stems

curve upwards at their extremities and rise to about one foot, producing

fairly large, ovate leaves, which are in opposite pairs, rather fleshy,

very smooth in texture, and of a bright green.

From each

leaf axil arises a raceme of small, very bright blue flowers, the upper

petal of each possessing dark blue veins, which form honey-guides to the

bees and flies which visit the flowers.

The Water

Speedwell (V. Anagallis-aquatica) is a rather similar plant, but

its leaves are lanceolate, the racemes of flowers are rather longer,

whilst the blooms are smaller and pale blue in colour. This plant is

rather less common than the Brooklime, but is usually a stouter and larger

plant, being often as much as three feet in height.

The Marsh

Speedwell (V. scutellata) is a more slender, less robust plant, but

of a similar habit, the stem being covered in pairs of smooth, lanceolate

leaves. It can be identified from the other two Speedwells by the fact

that only one raceme of flowers is produced by each pair of opposite

leaves. The flowers are very small and flesh-colored with dark

honey-guides.

These

Speedwells are pollinated in the same way as the Alpine Speed-well (see

Chapter VI)

MARSH

WILLOW-HERBS

The

Willow-herb Family (Onagracea) is well represented in Britain and

eight members of the genus Epilobium are to be found within the

Highland area. The marshlands claim two of these species and they are of

widespread occurrence, especially by streams, ditches and lochs, and also

in wet meadowland.

The

Small-flowered Hairy Willow-herb (E. parviflorum) is not a very

conspicuous plant, but it is very successful in the life struggle. Below

the surface of the mud, it possesses a slender, woody rhizome giving off

many much branched roots. From its extremity arises a fairly tall, leafy

stem at the summit of which the flowers are produced.

If we dig

up a plant in the autumn, we shall find that the rhizome has given rise to

several pinkish buds, which in some cases may have produced short, scaly

outgrowths, known as offset which next year will give rise to new plants.

The

almost stalkless leaves are alternate and usually grow more or less

erect. They are covered with soft hairs which give them a greyish hue,

although in some forms the hairs are almost absent.

The

flowers are produced singly in the axils of the upper leaves and, although

they appear to have long stalks, they are in reality nearly sessile, the

apparent stalk being the long cylindrical ovary at the summit of which the

flower is produced.

It is

composed of four small pale rose petals arranged as a cup at the base of

which nectar by a disc on the summit of the ovary. The eight stamens form

two rings round the four-lobed stigma. The small, inconspicuous flowers

are visited by small bees and flies, but are probably more often

self-fertilized, as the narrowness of the cup keeps the stamens pressed

toward the middle of the flower where pollen may be left upon the stigmas.

After

fertilization the long ovary lengthens and swells until, when the seeds

are ripe, it splits open by four valves and seed are released. Each one

has a tiny tuft of silky hairs attached at one end and by this means

floats upon the wind to be distributed far and wide.

The

second species is the Marsh Willow-herb (E. palustre). It is very

widely distributed and climbs the mountains to well over 2,000 feet. Some

authorities believe that it is only a lowland form of the Alpine

Willow-herb which it greatly resembles, although, of course, on a much

larger scale. Like that plant it perennates by means of slender runners

and it has smooth, narrow leaves.

Its eight

stamens are in two rows, the anthers being at first situated below the

club-shaped stigma. Later on, however, the stamens of one row lengthen so

that the anthers are placed above the stigma, so that if cross-pollination

has not been effected the flowers can be self-fertilized. This must often

happen as the flowers are not at all conspicuous. The seeds are

distributed as in the preceding.

MARSH

FORGET-ME-NOTS

Our

Highland marshes possess another beautiful plant in the Water

Forget-me-not, of which modern botanists have distinguished three

species. The first is Myosotis palustris which, although not

common in the Highlands, may be found here and there south of the

Caledonian Canal, especially in the west. It frequents wet ditches and

the sides of streams and rivulets, usually forming dense masses.

It

possesses a creeping stem rooting at the nodes and becoming erect at the

extremity to give rise to weak, leafy stems about one foot in height. The

sessile, ovate leaves are almost smooth in this species. The flowers,

which are produced in a branched cyme, are of a beautiful, pale blue

colour, which matches the rain-washed sky of April, and as if to enhance

their beauty, they possess a yellow eye at their centre. They are

distinguished from those of the other two species by being over half an

inch in diameter, and are constructed and pollinated in a similar manner

to those of the Alpine Forget-me-not (see Chapter VI).

The

Tufted Forget-me-not (M. caespitosa) is a much more common plant

and I have found it in large quantities in the marshy Lochaber meadows.

It is a much branched plant with slender, hairy, erect stems and small

downy leaves. The tiny sky-blue flowers, which are produced in long

racemes arising from the axils of the upper leaves, are only one-sixth of

an inch across, and are thus distinguished from the other two species.

The

Creeping Forget-me-not (M. repens) has a short rhizome producing

numerous, leafy runners which help the plant to form large colonies. Its

erect stems and leaves are covered with long, spreading hairs, whilst the

pale blue flowers are about one-third of an inch across. It can be

distinguished from the other tow by the fact that the flowers have very

long slender stalks, and when they have been fertilized, these stalks bend

downwards. This species is widely distributed in the Highlands and has

been found at 2,000 feet in some mountains.

GOLDEN

SAXIFRAGES

We have

in Britain two Golden Saxifrages belonging to the Saxifrage Family. The

Oppoisite-leaved Gold Saxifrage (Chrysosplenium oppositifolium) is

to be found throughout the Highlands in marshy places by streams and

tarns, in boggy woodlands and up the mountain sides into the realm of

alpine plants. I have found it at least 3,500 feet up on Ben Nevis

forming large, green masses beside those beautiful fresh springs, where we

may find the Starry Saxifrage, the Alpine Stitchwort and the Alpine

Willow-herb. On the other hand, it can be found in bogs at sea-level in

the Western Isles.

The other

species, the Alternate-leaved Golden Saxifrage (C. alternifolium),

has a much more restricted range, being found in the eastern and central

Highland area and in Argyll. It is found in the same places as the other

species and also climbs to over 3,000 feet on the mountain sides. This is

yet another member of the flora of Ben Lawers.

Both

plants are of a low habit with delicate, creeping stems rooting at the

nodes and sending up many erect, leafy shoots which are never more than

four or five inches in height. The leaves in the former are bright green,

rounded, shortly stalked with a crenate margin, and they are always

opposite, and covered with a few weak hairs. In the latter the lower

leaves have longer stalks and they are always alternate.

The stems

branch above to form a spreading tuft of leaves. The stalkless flowers

are very small and golden yellow in colour, and are surrounded by leaves

which are often golden hued, hence the name of plant.

The

flowers possess not petals, the calyx taking on their function. They

possess eight tiny stamens surrounding the two-styled ovary, which stands

upon a nectar-secreting disc, the nectar glistening like dew in the sun to

attract small flies.

In a

young flower, the anthers will be seen to be placed at the centre of the

flower, but when they have shed their pollen they recurve exposing the now

mature stigmas. It has been suggested slugs, which abound in damp places,

pollinate the flowers by crawling over them, if so, then even these

miscreants have some good in them. |