|

INSECTIVOROUS PLANTS OF THE BOG-LANDS

One

bright morning in late July I decided to climb to the top of the

Graigellachie, that precipitous spur of the Monadhliaths standing like a

rampart behind Aviemore, and explore the surroundings of a mountain tarn

and its associated bog-land, situated in a depression beyond the summit.

The day

was warm and sunny, with a gentle wind that whispered softly through the

trembling Birches that clothed the craggy and scree encumbered slopes of

this great grey pile.

I climbed

up to the barren plateau that forms the summit of Craigellachie where the

green carpets of the Bearberry covered the grey slabs of stone which were

separated by patches of black bog.

From here

a magnificent view presented itself as one looked out across the wide

expanse of Speyside towards the Cairngorms. Below lay the great black

mass of Rothiemurchus Forest through which the Spey wound like a silver

serpent, while beyond the lochs lay like diamonds amid the blackness of

the Pines. And beyond all, like a great wall stretched the deeply cut

massif on the Cairngorms. From here Cairngorm, Ben Macdhui, Braeriach and

Cairn Toul were plainly visible and the deep glens of the Lairig Ghru,

Glen Einich and Glen Feshie were easily discernible.

It was a

scene of indescribable beauty bathed in sunshine, an ever-changing

kaleidoscope of colour, the purple moors, the black forest of pines, the

brown mountain sides, the silver lochs and green pastures forming a

perfect symphony in colour.

Leaving

this beautiful picture, I descended 100 feet through the heather toward

the little tar, lying behind Craigellachie. Around its edges grew small

mountain willows, for the rest the heather and needle whin were the chief

vegetation. Along the lower edge of the loch lay a large patch of mossy

bog, yellow with the Bog Asphodel Moving cautiously I flushed a curlew

who had been busy searching in the mud along the shore and flew off with a

mournful cry as if the spirit of the loch had taken flight at my approach.

The bog

was a little floral garden, where I found the beautiful innocent blooms of

the Cloudberry, the fragrant Bog Myrtle, the purple Butterwort and the

Round-leaved Sundew and its long-leaved relative along with numerous

sedges and bog grasses.

Here I

spent a delightful day alone with the sun, the gentle breeze and the

sparkling mountain air filled with the honeyed perfume of the heather.

I studied

the divers inhabitants of this interesting spot, and especially the

insectivorous plants.

It will

come as a surprise to many people to know that in the plant world there

are certain plants which trap and digest insects, in much same way as a

spider catches a fly and eats it. We are so used to the insect visiting

glower to steal their pollen and nectar, but that plants should actually

live on an insect diet is almost unbelievable.

The plant

I am about to describe are some of the most interesting in the world and

have been the sourced of much speculation and research since Darwin’s

classical experiments with them.

In the

bogs we can find two types of insectivorous plants occur, such as the

Bladderworts, but I shall describe them in another chapter as they are

actually aquatic plants.

SUNDEWS SUNDEWS

In

Britain we have three Sundews. They are the Round-leaved Sundew (Drosera

rotund folia), which is the common species; the Long-leaved Sundew (D.

long folia) and the English Sundew (D. anglica) are frequent

although less common than the first one. All three species are found in

the Highlands in bogs from sea-level up to 2,000 or 3,000 feet.

They are

among the strangest plants to be found in Britain, for they have reversed

the order of Nature and, like carnivorous animals, trap and digest flesh

in the form of small insects such as flies and mosquitoes.

The three

species are very similar and close study of D. rotundifolia will

apply equally to the other two.

If we

examine a single plant we shall find that it has a very small, weak root

system which is very small in proportion to the plant that it is supposed

to nourish.

The

rootstock is crowned by a rosette of almost round leaves on long slender

stalks, which are covered by long, reddish glandular hairs. The upper

surface of the leaf is also covered by many red hairs, each with a

glistening drop at its extremity which shines like a jewel in bright

sunshine. The leaves are quite different from those we are usually

accustomed to in the plant world, and one may be well at a loss to

understand their purpose.

If we

examine a number of these plants we shall find that a fly or gnat,

attracted by the glistening drops, alights upon the leaf and commences to

the lick the drop. Immediately we shall notice that the hairs nearest to

the insect move down and touch it, and then the hairs further away begin

to move also. The fly struggles to escape, but the honey-like drops that

tempted it are stickier than glue and it cannot move. Its struggles

excite the rest of the hairs which, exuding more and more sticky fluid,

enclose the fly like the tentacles of an octopus. They move under the

same principle that makes the tendrils of a clematis twine around a

support. Gradually the breathing pores of the insect are choked by the

sticky fluid and death arrives to still its sufferings.

When the

leaf has completely closed around the insect, special glands upon the

surface exude a fluid which is exactly similar to the gastric juices of

the stomach of an animal. The insect is slowly digested, the juices

entering the leaf by specialized glands. As soon as the fly is completely

digested the leaf opens again, ejects the indigestible portion such as

wings and is ready for the next victim. Thus the fly actually nourishes

the plant.

Darwin

made an exhaustive study of these plants feeding them artificially with

raw meat. He gave them indigestion by over-feeding them and poisoned them

with poisonous objects. He found that inanimate things such as leaves,

dirt or wood excited the nearest hairs which closed round the object only

to unfold when they found that the object was not fit to eat. In nature

this must often happen as the wind blows particles of sand, et., on to the

sticky hairs, but by this amazing selective capacity no vital juice is

wasted upon these useless substances.

One will

probably ask why it is that the Sundew has evolved this amazing way of

life. The reason is not difficult to find. As we have already shown, the

soil of the bogs is poor in certain vital elements, the chief of which is

nitrogen. Now this element is of great importance to the well-being of

plants and a certain quantity is necessary for healthy growth. Animal

life is rich in nitrogen and the flies and insects trapped by these plants

supply the nitrogen that is deficient in the soil.

The

flowers of the Sundew are small and white and arranged in a raceme at the

summit of a very fine flower stalk. The raceme is rolled up in a curve

when young, but gradually uncurves as the flowers expand.

The

flowers have a tiny calyx of five green sepals, within which are found the

five rather long petals which only open in sunshine. They are fertilized

by small bees and flies.

The

Long-leaved Sundew is distinguished from the preceding by the leaves being

more erect and long and narrow, gradually tapering into the stalk. It is

a less common plant than the former, although often found with it.

The

English Sundew is much like the long-leaved species, but the leaves are

longer and narrower, often over one inch long without the stalk, and the

flowers are rather larger than in either of the preceding species.

THE

BUTTERWORTS THE

BUTTERWORTS

In

Britain we have four species of Butterworts, of which three are found in

the Highlands, one species, the Alpine Butterwort, not being found beyond

the limits of the western Highlands.

[Electric Scotland Note: We have

been informed that the Alpine butterwort has been extinct in the British

Isles since 1919. Source: an email from Faith Anstey.]

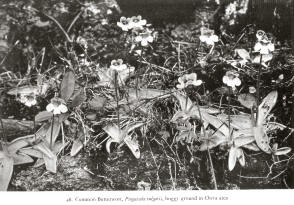

The three

species are found in similar situations to the Sundews and include the

Common Butterwort (Pinguicula vulgaris), a very common species

throughout the Highlands from sea-level to 2,500 feet or more; the Pale

Butterwort (P. Lusitanica), a small species confined to the western

Highlands although found elsewhere in Britain, and the Alpine Butterwort (P.

alpina), found only in Skye, Ross and Sutherland.

As in the

case of the Sundews a detailed description of P. vulgaris will

suffice for the other two species.

The

Common Butterwort belongs to the Lentibulariaceae, a family

composed of insectivorous plants, including the Bladderworts.

The

leaves, which are broad, rounded, rather succulent and arranged in a close

rosette, are of a light grayish-green colour and are covered with numerous

crystalline points which give them a wet and clammy appearance.

The

leaves are very interesting and well worth a close examination, the upper

surface being covered in a sticky fluid which is secreted by certain

specialized glands and is the medium by which the insects are trapped.

If the

surface of the leaf is scrutinized under a powerful lens one will find

that there are numerous glands scattered over it, some with stalks and

some without. Several thousands of these glands have been counted upon a

single leaf. They supply the digestive juices and the sticky fluid, which

shines in the sunlight and attracts insects who arrive in the hope of

finding nectar. As soon as they alight upon the treacherous surface they

are trapped.

The

glands then supply a ferment which gradually reduces the insect to a

liquid, only the hard portions, such as wings and legs, being left. Very

often the leaves curl up to form an improvised stomach. Other glands

absorb the liquid as it is formed. In this way the plant obtains

foodstuff which is absent from the poor, acid soil. The undigested

portions remain upon the leaves until they are washed away by the rain,

and the trap is then rest for fresh victims.

The

flower of the Butterwort is very handsome and of a deep purplish-blue, and

terminates a tall leafless stalk. The calyx, like that of the Snapdragon,

is lipped and consists of five segments. The corolla is also lipped and

is situated at right angles to the stalk, the lower lip consisting of

three broad lobes, the upper of two shorter segments. The throat of the

corolla is bell-shaped and is extended backwards to form a long, straight

spur at the base of which are situated the nectarines.

Two

stamens are situated near the roof of the throat while the stigma projects

towards the entrance.

An insect

alighting upon the lower lip must touch the projecting stigma with its

head and thus covers it with pollen. The stigma immediately springs up so

that when the insect withdraws its head it will not deposit any pollen

from the flower’s own stamens upon it, and thus self-fertilization is

avoided.

Butterflies and bumble-bees are the chief visitors as their tongues alone

are long enough to reach the nectarines at the base of the long spur.

The

Alpine Butterwort is very similar, but rather smaller in all its parts,

the flowers being of a pale yellow colour and having a very short obtuse

spur, whilst the middle lobe of the lower lip is long and broad. Its

insect visitors, as the short spur indicates, are short tongued and

include hone-bees and flies.

The third

species, the Pale Butterwort, is much smaller than the Common Butterwort.

The leaves are very similar, but the flowers, which are smaller than those

of the Alpine Butterwort, are pale yellow in colour, tinged with lilac,

and have very slender stalks, whilst the spur is short and slightly

curved. Honey-bees and small butterflies are the chief benefactors.

|