|

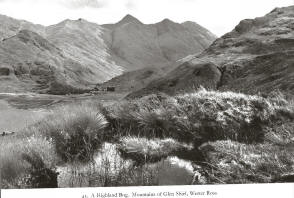

Most

visitors to the Highlands must have been struck by the huge areas of

bogland to be found in almost every situation, whether in valley bottoms,

on gently sloping hillsides, or on elevated plateaux.

Most of

us must have been disagreeably aware of them when tramping over the

mountain sides, and many the long detours one has been forced to make to

avoid these treacherous areas of water, mud and moss. All visitors must

have also been struck by the sight of Highland crofters cutting peat sods

for fuel along the drier edges of many a quaking bog.

To what

is due this peat formation? Why are such vast areas of mountain land

covered by bogs? The answer to these two questions is bound up in the

climatic factors of rainfall and temperature.

In the

warmer, well-drained soils, countless numbers of unseen organisms are

ceaselessly toiling to break up plant and animals remains into substances

such as ammonia and nitrates, chief among them being the soil bacteria.

The ammonia is oxidized into nitrites by a bacterium call Nitrosomonas,

and these are then oxidized by another bacterium, Nitrobacter, into

nitrates. Thus all organic material disappears in the course of time, the

products of its break-up enriching the soil.

The

bacteria responsible for this can only do their valuable work in the

presence of oxygen, and at a suitable temperature, hence they cannot work

in soil which is waterlogged, as the water drives all the air out of the

soil.

Now the

Scottish Highlands are a region of very heavy rainfall which is

distributed throughout the year. Wherever natural drainage is blocked,

the soil becomes waterlogged, with the result that flat, relatively

low-lying plateaux, such an Rannoch Moor, the bottoms of valleys, the

shores of lakes and gentle slopes become soaked with water which is often

visible at the surface. At the same time the average temperature over

most of the area is rather low.

Conditions such as these are not conducive to the oxidizing bacteria, and

so vegetable remains instead of being broken up endure in their fallen

state. They form acids which attack the mass of undecayed vegetation and

blacken it, but it is not reduced to mineral salts, with the result that

year after year the leaves and stems of heather, moss and fern add layer

on layer to the waterlogged soil.

In time

the pressure of the upper layers presses the lower layers into a hard

compact mass which can be cut into blocks, and drying can be used as

fuels.

After

centuries have passed the pressure increases until the lower peat becomes

a brown coal-like substance called lignite. Such a layer buried under

huge masses of soil and rocks will become real coal after the passage of

thousands of years.

Peat,

like a sponge, holds vast quantities of water and in course of time a deep

peat bog may be formed. This is an area of liquid plant remains covered

by bog moss, but although the surface appears quite firm, it is a

death-trap to the unwary as the drier surface layers cover a mass of

liquid into which the poor unfortunate sinks without hope of succour.

Owing to

the concentration of acid in the soil, the lack of oxygen and of mineral

salts, peat is a very infertile soil, which cannot support trees and is

shunned by most herbaceous plants.

Some

plants, however, have become specialized to this habitat, as for example

the insectivorous plants which depend for nitrates upon the insects they

catch. For this reason the Butterworts and Sundews are abundant in these

areas.

Typical

bog plants are the Grass of Parnassus (Parnassia palustris); the

Bog Myrtle (Myrica Gale); The Cloudberry (Rubus Chamaemorus):

the Marsh Cinquefoil (Potentilla palustris); the Bog Violet

(Viola palustris); the Cranberry (Vaccinium Oxycoccus); the

Bog Whortleberry (V. fuliginous); the Dwarf Birch (Betula nana);

the Bog Asphodel (Narthecium ossifragum) and the Scottish Asphodel

(Tofieldia palustris). Several species of Sedge, conspicuous among

these being the Cotton-grass, are abundant in the bog lands.

Many

plants show xerophytic adaptation due mainly to the exposed wind-swept

situations, not, as formerly believed, to the acid soil.

Grass of Parnassus (Parnassia palustris) Grass of Parnassus (Parnassia palustris)

This

plant is a very beautiful one and is abundantly common in the Highlands,

being found I bogs throughout the whole area and attaining a considerable

altitude. It flowers late in the year and one may often come across its

chaste white flowers as late as October in the milder werst.

The Grass

of Parnassus possesses a very short rootstock which is but slightly

imbedded into the mosses and mud of the bogs it inhabits. The leaves are

all radical and are produced on long, up-curving stalks, which take them

above the damp air immediately above the surface of the bog. They are

smooth and shining so that water vapour which condenses upon them will

immediately run off.

From the

midst of the leaves rises a slender flowerstalk, which attains nine inches

to one foot in height and possesses a single sessile leaf which is

produced half-way up the stem. The stem is crowned by a single large,

pure white flower, the petals of which run down towards the nectarines.

The

flower possesses a tiny clayx of five small ovate sepals, whilst the five

petals form a large saucer-shaped corolla which is very conspicuous. More

internally we find the five stamens, and beyond them five peculiar objects

which are actually modified stamens. They are flattened structures from

which protrude several appendages which are for all the world like little

golden-headed pins in a pin-cushion. These appendages form a fence around

the pistils, and the nectarines are found at the base upon their inner

side. In the centre of the bloom, we shall find the ovary with its four

stigmas.

The

reason for these modified stamens is rather a mystery. The Grass of

Parnassus is pollinated by flies, which may often be seen licking the

golden shining knobs as if they expected nectar to be secreted, in which

hope they are disappointed. It may be that they perform the function of

false nectarines to attract the flies, or on the other hand they may act

as a fence which forces the flies to approach the real nectarines in a

certain fashion which makes sure that transported pollen if left upon the

stigmas.

The

stamens move in over the stigmas on by one until all the pollen has been

shed, when they return to their original position. The stigmas then

mature and become receptive.

Flies are

the chief visitors, visiting the flowers both for pollen and nectar.

The Bog Myrtle (Myrica Gale)

Few must

be the number of hikers and walkers in the Highlands who do know the Bog

Myrtle, for apart from its widespread distribution and its abundance, the

sweet fragrant odour which issues from every bog makes the plant obvious

before it is actually seen. For, no matter where we may walk in the

Highlands, except at great elevations, we must meet with the bog myrtle

and its odour is a very part of the Highland scene. It is one of those

odour which form the complex smell of the Highlands, that nostalgia-giving

perfume composed of bog myrtle and peat, of pine and heather, that tang of

sea air and the cool breeze of the mountains which assails one as soon as

one alights from the train, and warns the traveller that he has once again

returned to the Highlands. That perfume which one can smell long after

one has returned to the city, as if it would pull us back to the purple

moors and brown mountain sides, to the black pines and the silver lochs.

The Bog

Myrtle itself is not a very attractive plant. It has no beautiful flowers

or beauty of form and yet for all that Nature has endowed it with this

glorious perfume contained in certain specialized cells in the leaves and

stems.

It is an

inhabitant of wet, boggy places and its roots delve down into the mosses

and peat to find a suitable anchorage. It attains two to three feet in

height although at higher altitudes it is considerably smaller.

The

brown, slender, woody branches are covered with lanceolate rounded

leaflets which are usually rather downy upon the under surface and contain

numerous resinous cells. The downy under surface is, of course, nature’s

means of protecting the stomata from excessive condensation from their

boggy surroundings. These leaves are shed in the autumn.

The

flowers of the Bog Myrtle are very unattractive, consisting of small,

brown, stalkless catkins which are formed along the extremity of the

branches often before the leaves have commenced to grow. They are

dioeciously, i.e. the female flowers are produced on one plant and the

male flowers upon another, as in the case of the willow.

The male

catkins, which are longer than the females, are composed of many brown,

imbricated scales, and have no petals or sepals. Six to eight stamens are

produced in each scale, the anthers being almost stalkless.

The

female catkins consist of two ovaries within each scale, at the base of

which the vestiges of a perianth may be seen. They are crowned by two

stigmas produced upon long styles.

The

catkins produce no nectar and, from the length of the styles, it is

obvious that they are fertilized by wind-borne pollen. This explains why

the flowers bloom early in the year before the leaves are fully formed.

After

fertilization the female catkins form a small resinous, nut-like fruit

containing one seed. The resinous coat protects the seed in its wet

surrounding until such time as the warmer weather makes germination

possible. If the seed falls into water it is well protected until such

time as it drifts upon a bank of soil and can commence an independent

existence.

The Cloudberry (Rubus Chamaemorus) The Cloudberry (Rubus Chamaemorus)

This

member of the Rubus genus is quite a different plant from the

others already described (see Chapter XII). It is to be found fairly

frequently in mountain bogs and may attain considerable altitudes, and I

have found it on Cairngorm at 3,500 feet.

It

produces a large creeping rootstock in comparison with which the above

ground portion of the plant seems ridiculously small. This is another

example of how mountain plants have become prominent geophytes.

Above

ground are produced short stems which seldom attain six inches in height

and are often much less. I have gathered plants in the Cairngorm at 3,500

feet in which the whole plant did not exceed two inches in height.

The

leaves of this species are not divided and are large and rounded, or often

kidney-shaped with a white cottony down on the under surface which

protects the stomata from the damp vapors continually arising from their

boggy surroundings.

The

flowers are large and conspicuous and are produced singly on a terminal

peduncle. Their pure white colour and spreading petals make them easily

seen and they are visited for their honey by bees.

After

flowering, a beautiful orange-colored fruit is formed, and as it is very

finely flavored it is much sought after for jams and jellies.

Its name

is Cloudberry is probably derived from the fact that the species is found

in those regions where clouds cover the sky for many days of the year.

The Marsh Cinquefoil (Potentilla palustris)

It is a

fairly common plant in many parts of the Highlands, being found in peaty

bogs, on the edges of lakes and in marshy places in many of the lower

coastal regions, and in the valleys and glens.

It is a

peculiar looking plant as it often assumes a bluish-purple hue, the stems,

glowers, and even leaves often sharing this colour.

Its

perennial rootstock sends up weak stems which are rather creeping at the

base, where they often send out adventitious rootlets. They become more

erect towards the extremity, but usually sprawl across the surrounding

plants and mosses.

The

leaves are produced on long stalks and consist of five almost equal,

oblong leaflets arranged like the fingers of a hand and are either quite

smooth above with soft hairs below, or are hairy on both surfaces. As

with the meadow sweet this is to guard against condensation.

The

flower which terminate long stalks are rather strange, being of a dull

purplish colour often approaching a brownish tinge. Like the Water Avens

they possess a double calyx which is usually tinged with purple, and is

longer than the corolla. The yellow anthers are conspicuous against the

dull purple background of the petals are the main attraction to insects.

They possess much nectar and, as in the case of the Water Avens, large

bees are probably the chief benefactors.

Bog Violet (Viola palustris)

It is

difficult to pick out the most beautiful species in this family of lovely

plants. No one can say that the gloriously perfume Sweet Violet is more

beautiful than the yell Mountain Violet with its large show flowers, or

than the Dog Violet whose numbers may tint the woodland banks with blue.

I am sure, however, that most people will agree that the demurely

attractive Bog Violet can hold its own with any member of the family.

If one

visit’s the bogs in May, one may be rewarded by the sight of tufts of long

stalked, heart-shaped, shiny leaves from the midst of which arises a

slender stalk crowned by a delicate, lilac-blue flower. This is the Bog

Violet.

It

possesses a long, slender, creeping rhizome which may extend for a

considerable distance through the soft peat and bog mosses, and at

intervals gives off slender white roots which push down into the peat,

whilst tufts of leaves are given off into the air.

The

leaves have beautiful crenate edges and are completely smooth and shiny.

The

flower has the structure of the typical violet, but is very small, the

lilac petals being delicately marked with dark veins, whilst the spur is

very short. The flowers are visited by small bees.

The

plants also produce cleistogamous flowers in the same way as the Wood

Sorrel, and these ensure that seed is set if the showy flowers are not

visited by insects, as must often happen in bad season.

THE

BOG VACCINIUMS

A very

typical bog plant is the Cranberry (V. Oxyoccus), which may be

found, if one is lucky , in some Scottish peat-bogs. I say ‘if one is

lucky’ because this plant is rather local in distribution, and is not to

be found in every peat-bog that one may chance upon.

It is

very difficult from the other members of the Heath Family that we have

dealt with, but shows its affinity to the whortleberries by its very

similar red fruit.

The

Cranberry possesses very slender, wiry stems which creep over the surface

of the bog, climbing over the mosses and other small plant and often

forming matted carpets. The stems send out roots at intervals.

The

leaves are evergreen, very small and egg-shaped, and their xerophytes

natures is shown by the fact that their edges are rolled over as in the

case of the Trailing Azalea and the Heaths. Thus most of the stomata on

the under surface are enclosed between the rolled-in surfaces. The under

surface is grayish-blue in colour from a waxy covering which prevents

water soaking the surface and blocking the stomata. This s a very

necessary precaution for a plant creeping over a wet surface.

The

flowers are solitary at the summit of a long, slender, drooping peduncle.

Unlike the other whortleberries the corolla is not campanulate or

vase-shaped, but instead is deeply divided into four bright red segments

which spread outwards and are often recurved, with the result that the

stamens are fully exposed. They are visited by small bees, and flies

which pollinate them.

The

flowers are followed by bright red berries which are greedily devoured by

grouse and blackcock which are instrumental in distributing the seeds.

The Bog

Whortleberry (V. uliginosum) is a very different plant, but much

more common and it may be found at considerable altitudes in the

Highlands.

It

resembles the Whortleberry (V. Myrtillus) (see Chapter XI) very

much, but may be distinguished from that species by the fact that its

branches are almost cylindrical and not angular, it is also much smaller,

more woody and more branched, the leaves being smaller, but thin and

deciduous. The flowers are very similar, whilst the fruit cannot be

distinguished by size or colour.

Dwarf Birch (Betula nana)

This is

another shrubby plant which, like the Bog Myrtle, prefers bogs for its

habitat. It is a very different plant from its relative, the Silver

Birch, and rarely attains the stature of a tree, and although luxuriant

specimens twenty feet high may be sometimes found, it does not usually

exceed three to five feet.

The plant

is at once known by its leaves, which are different from those of any

other British shrub. They are very short, rarely more than half an inch

long, almost circular in form with beautifully crenated margins, dark

green in colour and completely smooth and shiny.

The

catkins are similar to those of the Silver Birch, but are very small, the

males ones being oblong in form, whilst the females are thinner and only

about a quarter of an inch in length.

They are

wind pollinated and the seeds are winged as in the case of the Silver

Birch.

Bog Asphodel (Narthecium ossifragum)

This

plant is very abundant throughout the Highland area and is often the

dominant member of the vegetation. Before the flowers are in bloom, the

plants appear like those of rushes; however, the Bog Asphodel is a member

of the Lily Family.

The

rootstock is tough and woody, and buried in the mud and peat, giving rise

to a stiff, erect stem about six inches in height, the lower part of which

is covered by the remains of the dead leaves of other season.

The

actual leaves are narrow, flattened and grass-like in form, and are

arranged in two rows on each side of the stem, in much the same way as

those of the Iris. They are glabrous, deep green and shiny, and when the

plants are growing in large colonies, the resemblance to some species of

sedge is very marked.

The

flowers are produced at the summit of the stem to form a dense spike. The

perianth is constructed of six members, each of which is lanceolate,

sharply pointed, widely spreading, green on the outer surface and bright

yellow on the inner one, hence when the flowers are fully out the spikes

are very conspicuous.

The

flowers resemble those of the Jointed Rush or Toad Rush, and for this

reason some botanists have placed this plant in the Rush Family.

The six

stamens are beautiful objects, their filaments being covered by a thick,

white wool. The ovary is very pointed and terminated by a single stigma.

The flowers are visited by flies, which are probably the chief pollinating

agents.

After

fertilization the flowers are followed by long, orange-read capsules.

Hundreds of plants, each with its spike of orange-red fruit, make a

delightful splash of colour in the autumn, when most bright hues have

faded from the bog lands

Scottish Mountain Asphodel (Tofieldia

palustris)

The plant

resembles the Bog Asphodel, but is much smaller in all its parts and much

less common. The leaves are in two rows, and are sword-shaped and very

narrow.

The

flowers, which are greenish-yellow in colour, are produced in dense,

terminal spikes and are very similar in structure to those of the

preceding.

It is

usually found in elevated stations and is rarely found below the 500-feet

contour.

Bog Orchid (Malaxis paludosa)

The

Highland bogs have also their own orchid, a tiny plant to found in

sphagnum-bogs, here and there throughout the whole area. It is a very

difficult plant to discover, because the flowers are green in colour and

hence lose themselves against the bright green background of mosses.

If we

carefully extract the plant from its mossy bed, we shall find that it

consists of a tiny bulb suspended among the lower moss stems and anchored

by several fine roots given off from the base of the bulb. These toots

ramify among the mosses and do not enter the soil. It thus resembles

those tropical, epiphytic orchids which perch upon the branches of trees

and have no contact with the soil.

From the

summit of the bulb arise three or four oval, concave leaves. If we

examine them we shall find that the upper part is fringed with minute,

greenish tubercles. These are actually bulbils and from some of them, if

we look closely, we may see the rudiments of two or three leaves. The

tubercles are freed by the decay of the leaf margin and they drop off to

form new plants. This is yet another example of vegetative reproduction.

The erect

flower-stalk may be four inches in height in luxuriant specimens, but is

often no more than two inches high. It is terminated by a slender raceme

of very small, greenish-yellow flowers.

If we

examine a single flower under a lens, we shall see that there are three

narrow, outer, perianth segments (sepals), two pointing upwards and

downwards. There are three petals, two very minute and spreading

laterally, and the third forming the lip (labellum). The latter is

remarkable because instead of being pendent it is erect and forms a hood

over the stigmas and anthers.

The

flowers are pollinated as in the case of the other British orchids (see

Chapter XX). In this plant, however, each anther cell contains a pair of

pollinia which are in the form of very think leaves of waxy pollen, the

grains of which never separate.

In spite

of their small size and inconspicuous colour, the flowers are highly

attractive to insects and most of the flowers in the spike are usually

cross-pollinated.

This

little plant is interesting as it is the only British representative of

the Malaxeae tribe of orchids, which includes a large number of

magnificent tropical species.

Marsh St. John’s-wort (Hypericum elodes)

To find

this lovely little plant, we must confine our search to the spongy bog

lands of Argyll and the Hebrides, for it belongs to the Atlantic flora and

is not found far away from the influence of that ocean.

I have

found it only once in a mossy bog in Argyll. I shall never be in any

doubt as to its identity if I chance on it again, for it has a strong

disagreeable, resinous odour which is difficult to remove from the hands.

It is also remarkable in being covered with white woolly hairs, although

inhabiting wet saturated places.

Its stem

creeps for about one foot over the surface of the bog and roots at the

nodes. It is clothed with a thick mantle of white hairs as are both sides

of the round, opposite leaves, which clasp the stem by their bases. The

hairs help to keep the leaf surfaces free from water, which would

otherwise clog the stomata and impede gaseous exchanges. Hairy leaves are

met with in other bog and marsh plants such as the Hairy Willow-herb and

the Water Mint.

The stems

turn upwards at their extremities and produce a few-flowered, leafless

cyme of pale, yellow flowers. The sepals are edged by a fringe of

glandular teeth which effectually bars further progress to creeping

insects such as ants.

The

flowers are visited by bees and flies for their pollen, no nectar being

secreted.

Marsh Penny-wort (Hydrocotyle vulgaris)

This

creeping perennial is to be found throughout the Highlands and is fairly

common in the lower marshes and bogs and is rarely found above 1,500 feet.

Usually

our first acquaintance with this plant is a mass of round, shiny leaves

covering the mosses and other lowly herbage of the bog. The stems are

only apparent if we pluck a handful of moss, when we hall find that each

leaf is attached to a long, weak stalk, which in turn arises from a

slender, creeping, white stem. The latter creeps in all directions among

the mosses and gives off bunches of fine roots at the nodes. The plant is

perfectly specialized to its habitat and its delicate stems and roots are

kept moist and protected from drought and cold by the soft blanket of

mosses.

The

leaves are quite round, with beautifully crenate margins, and are peculiar

in being attached to the stalk at their middle point; such leaves are

known as peltate.

From the

axils of the leaves arise short, leafless stalks which are terminated by a

single tiny head of minute flowers, with sometimes one or two whorls lower

down.

It will

come as a great surprise to my readers to know that this plant belongs to

the Umbelliferous Family. The tiny flowers remain concealed in the mosses

and are self-fertilized, although small creeping insect may accidentally

cross-fertilize them in crawling over the blooms.

BOGLANDS SEDGES

Let us

visit any large stretch of bogland in summer; one can pick out any corner

of the Highlands one chooses. My choice would be a lovely stretch of

green moss and running water near the shores of Loch Coruisk in Skye, in

the very shadow of the Black Coolins. Others may prefer that lonely and

yet strangely beautiful area, where Rannoch Moor runs up to meet the Black

Mountains; here you can pick and choose, as there are bogs everywhere. No

matter what place you choose, you will be certain of finding most of the

plants described here.

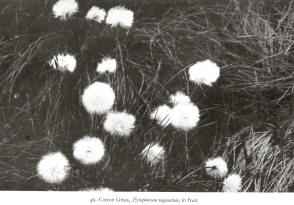

Having

arrived at your bog, you will probably be struck by a host of nodding

silky white tassels, shining in the sun and swaying gracefully in the

wind. This lovely sight is caused by the fruiting spikes of the Cotton

Grass, the seeds of which are surrounded by very long, silky hairs.

Cotton Grass (Eriophorum vaginatum) Cotton Grass (Eriophorum vaginatum)

We have

two species in Britain, the Hare’s tail Cotton Grass (Eriophorum

vaginatum) and the Common Cotton Grass (E. plystachion).

If we dig

up a plant of the Hare’s-tail Cotton Grass from the soft peat, we shall

find that it possesses a long whitish rhizome, giving off many tufts of

roots and at intervals leaves and stems.

The

leaves are cylindrical in form, the edges being rolled up on each other.

This is, of course, a xerophytes adaptation, and thus when temperatures

are low and strong winds are sweeping the bogs, the plants run no risk of

excessive transpiration.

The stems

are terminated by a dense spike of long, silky hairs. If we had visited

the bog in May, we should have found that the silky tufts were not in

evidence, instead each stem would have been found to be terminated by a

yellowish spike of flowers, similar to those of a sedge except for the

fact that both pistils and stamens occur in the same flowers.

If we had

dissected out a flower, we should have found that it was composed of

olive-green bracts surrounding three stamens on long, slender filaments,

and a tiny ovoid ovary surmounted by a long, trifid stigma. Around each

ovary would have been seen several short bristles, and it is these which

lengthen after fertilization to form the silky tufts so conspicuous in

summer.

Whilst

searching among the plants of Cotton Grass, we may notice many stouter

looking plants bearing several head of hairs instead of a solitary one.

This is the Common Cotton Grass. It is very similar to the preceding, but

the spikes of flowers are produced in an umbel which is overtopped by one

or two long green pointed bracts.

When in

seed the many dense tufts of hairs, which may exceed one and a half inches

in length, form a very beautiful object indeed.

As we

examine the many different inhabitants of our particular bog, we may

notice masses of stiff, rush-like stems terminated by handsome, dark,

shining brown, dense heads of flowers. This is the Bog-rush (Schoenus

nigricans) in which the flowers are similar to those of the sedge, but

are not unisexual. Each stem is terminated by two or three brownish

bracts which have long, stiff points and overtop the spikes. The leaves

are small and not very conspicuous, forming dense tufts at the base of the

stem.

Bunches

of fine, wiry stems about nine inches high and producing a terminal spike

of pale, almost white, spike lets betray the presence of the White

Beak-sedge (Rhynchospora alba), which produces one or two small,

lateral spikes well below the terminal one, whilst a long fine, greenish,

pointed bract overtops each spike.

We may

also be attracted by another plant producing a head of very dark brown,

almost black, spike lets. Its leaves are small and cylindrical, whilst

the flowers are partially concealed by large, brownish bracts. This the

Narrow-leaved Blysmus (Blysmus rufus), which is very abundant in

the Scottish Highlands.

Besides

these particular species of the Sedge Family, we may find many different

species of the real Sedges (Carex). We have over seventy species in

Britain, many of them being bogland plants and many of them are extremely

abundant. Their general characteristics have already been described in

the chapter on the Mountain Pastures, and it would be out of place in this

book to attempt to describe the numerous species, but those who are

interested and have plenty of patience, and would like to discover the

names of the different varieties, must refer to a British flora.

A very

interesting and beautiful collection may be made of these plants, and

although at first the various species appear very similar, it will be

found that each one has an individuality of its own. Their search and

discovery will add much interest to many wearisome tramps across the

desolate spots of the Scottish mountains.

I may add

there that to those of you who wish to discover all there is to know about

Highland botany and plants, and who posses a microscope and plenty of

patience, there is a large field of discovery open among the mosses and

their close relatives the liverworts. These lowly plants make up a large

part of the mountain flora and many are peculiar to the Highlands.

Many

interesting ferns, club mosses and horsetails may be found on the Scottish

mountains, so that there is plenty of scope for those who would study our

own mountain plant life. The search for these plants will take you into

many a spot which would not be visited under other circumstances, whilst

the arrangement and study of your collections will give you untold joy and

happiness during the long winter evenings when all Nature is sleeping.

|