|

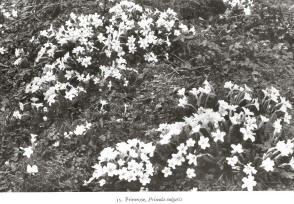

The Primrose (Primula vulgaris) The Primrose (Primula vulgaris)

I left the south in late May, at a time when

the Wild Hyacinths filled the woods with their glorious blue flowers and

sweet perfume. The Wild Cherry, the Cowslips and the flowers of early

summer were already in bloom. The Primroses, which had been in bloom

since January, were now almost all withered and only the rosettes of

wrinkled leaves marked their place.

Yet in twelve hours I was in Speyside and had

arrived to all the freshness of early spring. The Birches were clothed in

the pale green of newly opened leaves, and the sparkling mountain air

ruffled the opening glowers of the Bird Cherry and wafted its sweet

perfume along the forest glades. But the loveliest sight of all was the

beautiful green banks covered in masses of yellow Primroses, their

delicate perfume mixing with that of the Bird Cherry.

I think, and I am sure most of my readers will

agree with me, that the woodlands yellow with the pale shy flowers of the

Primrose, make one of the most beautiful of all Nature’s masterpieces.

Its arrival, after the cold and harshness of winter, into a world just

awaking from a long sleep bring colour and perfume into the countryside,

and hope into the hears of men, for when the primrose is in flowers, then

we all know that spring is on its way, and that after the long night of

winter the warmth and life will return.

All along the foot of the sheltering hills

where the Oak and Hazel flourish on the steep sides and all along the road

winding round Loch-an-Eilean, the primroses starred the green hillside,

and colonies were everywhere beneath the trees and in the clefts of the

rocks where the trickling water moistened their roots.

The common Primrose is abundant throughout the

Highlands wherever oak woods or shady moist banks and meadows are to be

found. I have pick its blooms on the shores of Loch Nell in Lorne, beside

the sea in Morar, and along the wood girt shores of Loch Lomond, while

everywhere the railway cuttings are resplendent with its pale yellow

stars.

One will not find the Primrose at high

altitudes, and beyond 1,000 feet it cannot stand the rigours of the

Highland climate. From sea level to 600 feet is the most favored zone.

Probably few people are aware of how

marvelously the Primrose is adapted to the battle of life and why it is so

abundant throughout a large part of the temperate world.

Let us examine closely a Primrose clump and

study its structure and that of its flowers.

If we dig up a clump, we shall find that the

main rootstock penetrates deeply into the soil and its thick. This

underground stem acts as a storehouse of food in order that the plant can

commence growth early and take advantage of the first mild days of late

winter and early spring.

Above ground the rootstock is crowned by a

rosette of fairly large leaves. These leaves are obovate in shape and

much wrinkled upon the upper surface which is of a bright green. The

under surface is covered with a fine down which prevents the stomata from

being swamped by water of clogged by damp in the most places that this

plant always inhabits. The rosette structure allows them to receive as

much light as possible in their shady home.

>From the middle of the leaf rosette spring

several hairy flower stalks, which are fine and usually bend slightly

towards the apex. They are covered with soft reddish hairs and these

prevent crawling insects from reaching the flowers.

Each flower stalk is terminated by a single

large pale yellow flower, which has a tube-like clayx composed of five

segments. The corolla is tubular in the lower part, the petals being

united below, but beyond the edge of the calyx tube the petals are free

and spread at right angles to the tube to form a wide circular bloom.

This makes the flower very conspicuous and forms a fine landing stage for

winged visitors.

The ovary is situated at the base of the tube

and is surrounded by nectarines. It is surmounted by the style and

stigma. The stamens are included in the tube.

If we cut open the tubes of several flowers

obtained from different plants, we shall find that in some flowers the

stamens are inserted at the entrance to the tube, but that in others they

are inserted near the middle of the tube. In the first type, the style is

short and the stigma arrives at the middle of the tube in the same place

as the stamens in the second type. In the second type, the style is long

and the stigma situated at the entrance to the tube.

This structure, which is know as heterostylism,

is an interesting adaptation to ensure cross-fertilization.

An insect, on visiting a flower with a short

style, brushed the anthers at the entrance to the tube with the base of

its proboscis and its face. On going to a long-styled flower afterwards

it will leave the pollen on the stigma at the entrance to the tube, before

receiving the pollen from the lower anthers upon its proboscis.

Similarly, pollen is transferred from the low anthers to the short-styled

flowers.

Darwin proved in a number of exhaustive

experiments that only when pollen from long stamens was transferred to a

long-styled flower, or from short stamens to a short-styled flower, was

the maximum yield of fertile seed obtained. If by an chance pollen from

the long stamens fell upon the short style below or vice versa, only a

poor yield of seeds was obtained.

This then is a very interesting example of one

of the diverse fashions in which Nature attains her ideal of

cross-fertilization in the plant world.

The chief visitor to the Primrose species of

fly resembling a humble-bee, which is attracted by the conspicuous pale

yellow flower, and also by its sweet elusive perfume. Around the throat

of the tube is a circle of darker yellow which marks the entrance. This

fly has a long tonque and so is well able to reach the nectarines at the

base of the long tube.

The seeds of the Primrose are very numerous

and very small and light. They are distributed by the wind which jerks

them out of their capsule to a considerable distance from the parent

plant.

The Primrose is not solely dependent on its

seeds as offsets occur at the base of the parent plant. These result in

the large clumps which this plant often forms.

Thus one can see how well equipped in the

Primrose in the struggle for existence and why it is such an abundant

plant.

Wood Anemone (Anemome nemorosa) Wood Anemone (Anemome nemorosa)

This plant, or as it is often known, the

Windflower, is another woodland plant which is abundant in the Highland

woods, especially in those drier woods where the Birch is the chief tree,

because, unlike the Primrose the Wood Anemone loves dry, light soils.

Like the Primrose, it flower when the woods

have stirred from the deep sleep of winter and it is one of the first

flowers to welcome spring on its return.

Its name, anemone, means the flower of the

wind, and it is certainly a beautiful picture to see the wood anemones

dancing in the wind on some exposed hillside wood.

It is a very dainty plant, but its whole

lightness makes it well suited to the windy season when if flowers.

Below the soil it possesses a long tough

rhizome which runs horizontally through the soil acting as an anchor to

support the leaves and flowering stem, whilst the wiry, pliable flower and

leafstalks are very well able to stand up to strong gusts.

The large leaves which terminate the stalks,

are deeply cut into five lobes which are again much divided, and are

silkily hairy above and below.

The flower stalk, which is from three inches

to six inches in height, is terminated by a single large, white flower,

below which is situated a whorl of three-lobed, leaf-like bracts, known as

the involucre, which protects the flower whilst in bud.

The flower itself possesses no petals, the

five sepals taking their place. These sepals are large and glossy white

within, but the outer surface is often shaded to rose-pink or violet. It

is large and star-like and very conspicuous against its dark green

involucre and leaves. Within are included the numerous stamens and

stigmas which are arranged upon a common receptacle.

The flowers do not produce any nectar and are

without perfume, and hence are only visited by insects for their pollen,

certain early bees being the chief visitors. The flower assumes a nodding

position in cloudy weather and then may become self-fertilized as pollen

falls from the anthers on to it own stigmas.

Chickweed Wintergreen (Trientalis

europaea)

This dainty plant, like the Wood Anemone,

loves light soils and is found in similar situations. It is, however, a

much more local plant, being found in birch woods in one particular spot,

but being absent in other places which seem to be equally suitable.

There are many points of resemblance between

it and the Wood Anemone although it belongs to the Primrose Family.

It has a tough rhizome creeping below the

surface of the soil and sending up a wiry tough stem which is about three

to six inches high but no separate leaf stalks.

The stem is crowned by a whorl of five or six

leaves which vary in size, but are usually ovate and without

indentations. From the centre of the leaves spring one to four slender

flower stalks each of which bears in mid-summer a single white or pinkish

flower, rather smaller than that of the Wood Anemone.

The flower, unlike the Wood Anemone, has a

clayx of seven green very narrow pointed sepals and seven large white

petals which are united below and have a yellow ring near the base.

Like the Wood Anemone, the Chickweed

Wintergreen produces no nectar, but as it flowers during summer, it has a

much better chance of being cross-pollinated, as insects are so much more

numerous and come to this plant for pollen, being attracted by the

conspicuous flowers.

In order to make cross-fertilization more sure

the single stigma matures before the anthers and on being fertilized it

withers, whereupon the anthers mature.

In bad weather when insects are not abroad

self-fertilization takes place.

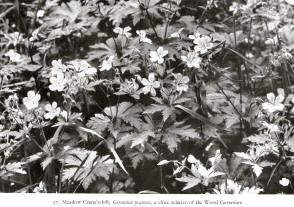

Wood Geeranium (Geranium sylvaticum) Wood Geeranium (Geranium sylvaticum)

Britain is rich in wild geraniums, at least

twelve being recognized as distinct species. They are all beautiful

plants and their habit makes then unmistakable. The Wood Geranium is

itself a very handsome plant and by many people considered the loveliest

British representative of its family, whilst its large flowers make it a

good subject for a detailed study of what is a very interesting genus.

The Wood Geranium is very common in the

Highlands and prefers the rough, rocky thickets which occur along the

edges of woods and that grow up along the foot of screes, and on the stony

edges of pastures. It is widespread wherever such habitat occurs up to

700 feet or 800 feet, and may be found in flower throughout the summer.

If we examine a plant carefully, we shall find

that the rootstock is very short, thick and woody, and covered in the

brown scales which are in reality the withered stipules of the old radical

leaves.

The rootstock is crowned by a rosette of

several leaves, which have very long stalks. These leaves, which are very

beautiful and are divided almost to the base, with five or seven pointed

lobes which are much cut and toothed on the edges, are covered in long,

silky hairs which protect them from cold and damp.

>From the middle of these leaves arises the

tall flower stalk, which may attain two feet, or even more in moist,

sheltered situations, and is clothed with a few small leaves which are

similar in form to the radical leaves. The stem forks repeatedly in the

upper part, the first for usually arising from two opposite leaves, each

fork being terminated by a flower stalk from which arise two flowers on

short erect pedicels.

Each flower is large, about one inch across,

and of a beautiful rich purple colour. It is a marvelous structure and

well worth studying, as it was from this very species that Sprengel drew

many of his interesting discoveries with regard to the pollination of

plants by insect agency.

The flower consists of five ovate sepals which

are covered in a fine down and end in a fine awl-like point, and are well

able to protect the flowers from damp and cold until they are ready to

open.

The five petals, which are large and showy,

are obovate in shape with a short claw. The lower part of the petal is

covered with short hairs situated above the nectarines and protecting them

from moisture, just as eyelashes prevent the perspiration running down

into our eyes. The filaments of the ten stamens are also covered with

hairs for a similar reason, so careful is this plant to conserve the

nectar for its insect visitors.

Each petal has several dark veins running down

towards the nectarines to act as honey guides to show insects where to

search for the nectar.

Within we find the ten stamens, five of which

have short filaments. The anthers mature before the stigmas, the long

stamens shedding their pollen first and then the short stamens. When all

the pollen is shed and all danger of self-fertilization has passed the

stigmas mature and become receptive. The ovary, which is five-lobed is

surmounted by a long, fine beak whose tip is divided into five spreading

stigmas which remain pressed close together until the stamens wither.

The chief visitors are butterflies and many

types of bees, although it is probable that the larger bees are the chief

benefactors.

Thus we see how beauty of flowers is arranged

not to delight the human eye, but to attract that of their special

benefactors the insects, and so obtain the goal of all highly developled

flowers, cross-pollination.

When the ovary has become mature it resembles

the head of a bird with a long beak, hence the name Crane’s-bill and

Stork’s-bill given to various members of the Geranium Family.

As the outer surface of the ovary dries, it

becomes taut and elastic. Then on a sunny day the ovary splits into five

segments and as it does so, the tension being suddenly released, the

segments each containing a seed fly off a considerable distance from the

parent plant. Thus the Wood Geranium increases its range of growth and is

not crowded out of existence by the competition of its own offspring.

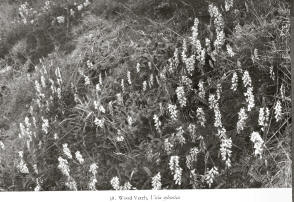

VETCHES OF THE HIGHLAND WOODS

In the Highlands we have three Vetches which

inhabit the woodlands. They are to be found along the edges of woods

where scrubby thickets exist or in the woods themselves wherever they

become more open. Their climbing habit adapts them beautifully to these

wooded regions.

They include the Tufted Vetch (Vicia Cracca),

a beautiful, bluish-purple flowered species, the Wood Vetch (Vicia

sylvatica), which often attains a great length and has large white

flowers, and the Upright Vetch (Vicia Orobus), which is found in

more open situations than the previous two species and has more erect

stems.

The Tufted Vetch (Vicia Cracca)

This plant is a perennial whose stock is

hidden among the fallen leaves and the shrubs on the forest floor. If

the plant were to grow up in this spot with an erect stem, like most

plants do, it would never be able to rise above the neighboring plants

plants and in the shade prevailing in the woods, it would be forced to

flower inconspicuously among the rank growth of brackens, heaths and

birches which forms the undergrowth of our Scottish woods. The Tufted

Vetch, however, being an ambitious plant had other ideas in view. Its

stock sends up weak stems clothed in pinnate leaves whose common leaf

stalk produces a much branched very sensitive tendril which seizes upon

the nearest support ad thus supports the stem. As the stems grow in

length they climb over the surrounding vegetation by means of these

tendrils until, having attained the brighter regions above, the Vetch can

produce its flowers where they are most conspicuous to insect visitors.

Being devoid of scent this is very important for the continuation of the

species, insect visitors being dependent upon their sight to find the

blooms.

The stems may attain a length of three feet,

or even more, and are covered in leaves consisting of many narrow

leaflets. The small, bright bluish-purple flowers are produced on long

stalks rather longer than the leaves, and are arranged in a long,

one-sided raceme which is very conspicuous. After flowering they give

rise to a pod about one inch long containing six or eight seeds.

This plant is common throughout the Highlands,

being often found along the borders of fields, and on roadside banks, as

well as in the thickets and open woods up to about 1,500 feet.

The Wood Vetch (Vicia sylvatica) The Wood Vetch (Vicia sylvatica)

This Vetch is similar in habit to the

preceding and grows to great lengths, often climbing to the top of small

trees, a length of six to eight feet being quite common. The leaflets are

few and broader than in the Tufted Vetch, while the flowers are longer

than in that species, and are arranged in very long racemes. They are

usually white streaked with blue, and are more conspicuous in the woodland

shade, showing us that this species is better adapted to its woodland

home. It is rather less common than the Tufted Vetch and prefers more

wood regions than that species.

The Upright Vetch (Vicia Orobus)

In this species the tendrils are missing,

their place being taken by a short point at the end of the leaf stalk. It

produces stems which are more erect than in the case of the other two

species and does not climb to the same extent. The leaflets are narrow,

and consist of from eight to ten pairs. The flowers, which are produced

on stalks about the same length as the leaf stalks, are crowded into a

close raceme of six to ten rather large, purplish-white blooms.

The more upright growth, the absence of

tendrils and the short raceme are explained by the fact that it prefers

more open situations, and may be found in mountain pastures, and in rocky

places, as well as on the edges of woods and thickets. It is not a very

common plant, being confined to Perth and Angus in the south-east, and

Inverness-shire, Mull, Skye and Sutherland in the west.

THE PEAS OF THE HIGHLAND WOODS

The Wild Peas include two species; the

Tuberous Pea (Lathyrus montanus), a very common plant in woods,

thickets and bushy places, and the Black Pea (Lathyrus niger), a

very rare plant found in one or two places in rocky woods in Perthshire

and Forfarshire.

The Tuberous Peas obtains its name from the

fact that the perennial rootstock consists of small tubers, which,

conserving as they do nourishment throughout the long winter months,

enable the Tuberous Pea to commence growth early in the year and begin

flowering as early as possible before the other members of the Pea Family

enter into competition for insect visitors.

The rootstock sends up smooth stems which are

almost erect and attain a height of six inches to a foot, in luxurious

specimens considerably more. These stems are clothed in pinnate leaves

the leaflets consisting of two pairs, although three or four may sometimes

occur, their common stalk being terminated by a fine point or sometimes by

a leaflet, but there are no tendrils as in most members of this family.

The flowers are produced on slender flower

stalks and form a close raceme of from two to four bright reddish-purple

flowers, which are followed by a long, smooth pod.

The Black Pea is very similar to the

preceding, but does not produce tubers. Its stems are usually longer,

often attaining two feet, whilst the leaves consist of from four to six

pairs of leaflets.

The flowers are produced in a short raceme and

are six to eight in number and very similar to those of the tuberous pea.

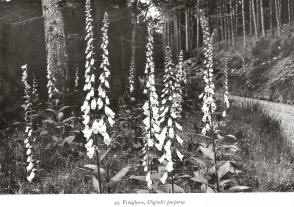

The Foxglove (Digitalis purpurea) The Foxglove (Digitalis purpurea)

This is one of our most handsome British

plants with its graceful spire of purple or white flowers. It is a fairly

common plant in the Highlands and a bank adorned with dozens of these

plants is a sight worth remembering. We can find it in rocky waste places

on the edges of woods and thickets, wherever there is protection from

fierce winds, and for this reason it sis not found above 2,000 feet.

I know several places in Argyll where the

white variety is almost as common as the purple one. In fact, in one

isolated thicket on the edge of a small lake, there appears to be a colony

of solely white flowers which may be due to continued inbreeding as no

other colonies occur in the vicinity.

The Foxglove is what is known as a biennial,

that is to say, it passes one year in the vegetative state and flowers

during the second year, after which the plant dies down.

If we visited a colony of this species in late

summer, we should find that it terminated a short erect hairy pedicel,

from the extremity of which the flower was pendent.

At the base of the showy corolla would be seen

the green hairy calyx of five free sepals.

The corolla is a large swollen tube, nearly

two inches in length, which widens out at the middle and is constricted

slightly towards the mouth and base. The mouth is nearly one inch across,

the lower portion protruding as a short, broad lip, the upper portion as a

very short, hardly noticeable lip.

The corolla is rosy-purple in colour, the very

beautiful interior being marked with whitish patches which are covered

with tiny, deep purple spots which are large and more prominent at the

centre. In the white variety, the corolla is cream colored and dotted

with black spots.

The inner surface of the corolla also produces

long, soft hairs, which effectually bar entrance to small or weak insects.

At the base of the corolla tube is a large,

green, conical, two-chambered, hairy ovary with a nectar secreting ring at

its base.

The flower produces four stamens, two of which

are shorter than the other two. They are so arranged that the four

anthers are in two tiers against the roof of the corolla, the stigma

being placed between them. The flowers are constructed for pollination by

the large bumbl-bees.

It is very interesting and instructive to

watch one of these large, clever insects visiting a flower, say a

newly-opened one. It alights upon the lower lip, halts for a moment and

then enters the tube and crawls in as far as possible, usually being

completely engulfed, for being a powerful it is not embarrassed by the

hairs. As it enters the corolla, the anthers in the rood will touch its

back, depositing pollen upon it.

In the young flowers, the stigma is not yet

receptive and hence there is no danger from self-pollination. To prolong

the period during which pollen is produced, the two upper anthers open

first, and then the other two; when the pollen is shed the anthers wither

and drop off and the two stigma lobes separate.

A bee, visiting an older flower, will thus

leave pollen upon the stigma which occupies a position similar to that

previously occupied by the anthers. Hence the stigma touches the bee’s

back just where it is covered with pollen.

Smaller bees and insects would be use to these

flowers as they would not touch the anthers or stigma.

The plant is very beautifully designed for

the bumble-bee because in the tall racemes the flowers open in succession

from the base of the raceme upwards, hence the older flowers are at the

base, the younger staminate ones being higher up.. The bumble-bee always

commences with the lowest flowers of the raceme, finishing with the upper

ones, hence it is obvious it will always pollinate the pistillate flowers

with pollen brought from a different plant.

After fertilization the corolla drops off and

the calyx enlarges and covers the ovary, which develops into a dry capsule

containing many light seeds. In autumn, the capsule splits and as the wind

shakes the tall stems, the seeds are thrown out, often to considerable

distances from the parent plant.

The plant is protected from herbivorous

animals by a poisonous substance digitalin which is found in all its

tissues.

This plant gives us yet another insight into

the amazing fashion in which the plant and the insect are related to each

other, and we realize to the full the truth of that well-used quotation;

‘Verily there are more things in heaven and earth, Horatius, than were

ever dreamed of in your philosophy.’

Rose-Bay (Epilobium angustifolium)

This beautiful plant is becoming increasingly

abundant in the Highlands, especially where wood and thickets have been

cleared. The hairy seeds travel long distances and this is the main

reason for the way this plant so quickly colonizes cleared ground.

It is yet another plant which passes the

winter buried in the soil only to awake into renewed vigor in the spring.

If we dug up an old plant of the Rose-bay in

the winter, we should find that the underground stem had given rise to

short, pink branches terminated by a large bud or by a rosette of leaves.

During winter the old stem decays and the new branches produce roots to

form new plants, which get off to a flying start, having drawn upon the

large amount of starch, etc., which was stored up in the old rhizome.

The new plants form a rosette of long, smooth,

lanceolate leaves which often have a reddish tinge.

>From the middle of the rosette arises a tall

flowering shoot clothed with alternate lanceolate leaves similar to the

radical ones. These become smaller towards the summit of the stem, which

may be as much as three feet high.

The beautiful flowers form a leafy raceme

towards the summit of the stems and this may be one foot in length.

Each flower is produced singly upon a short

pedicel arising from a leaf axil. Above the short stalk is the long,

cylindrical ovary, which is over one inch in length and appears like a

long stalk below the flower.

>From the summit of the ovary arise the four

spreading lanceolate sepals which are magenta colored and have a slight

advertising value. The sepals are united at the base to form a tiny cup

above the ovary, the fleshy summit of which secretes nectar.

The four petals which are produced alternately

to the sepals are large, spreading and cordate and inserted upon a short

claw. The corolla is about one inch in diameter and of a bright crimson

colour, and is so arranged that it hangs vertically, hence there is no

landing stage as in most bee fertilized flowers. The racemes are very

conspicuous and the plants are rendered much more so by their habit of

forming very extensive colonies to the exclusion of other plants.

A colony of Rose-bay is one of the most

beautiful sights in these islands, the tall crimson spikes swaying

gracefully in the wind and forming a glorious picture when framed against

a background of black pine trees.

The flowers produce eight stamens in two

whorls of four each, the outer whorl maturing before the inner one.

The stamens project downwards in front of the

flower, whilst their filaments form a closed dome over the nectary,

protecting it from rain and creeping and small insects. The flowers are

constructed for pollination by bees or butterflies, but the former are the

chief visitors. The corolla in these flowers is entirely an advertising

agent.

A bumble-bee on visiting a young flower

alights upon the hanging stamens, whose anthers dust the under part of its

body with pollen. It suspends itself from the stamens whilst it pushed

its proboscis between the filaments to reach the nectary. The style at

this time is curved down upon the lower petal and as the four stigmas are

pressed closely together, there is no danger of self-pollination.

After the pollen is shed and there is no

further danger of self-pollination, the style rises up to the position

originally held by the stamens. A bee on visiting this flower will alight

upon the style, and as its under surface is covered with pollen, it will

leave some upon the stigmas.

As in the Foxglove, the racemic arrangement of

the flowers is an adaptation to pollination by bumble-bees.

After fertilization the corolla withers and

the long, cylindrical ovary begins to swell. The seeds are produced in

eight long rows in the four chambers of the ovary, and each seed coat

produces a tuft of long, silky hairs. When the seeds are ripe, the ovary

splits open by four valves and the seeds escape, the silky hairs acting as

a parachute so that the seeds travel long distances before falling to

earth. Each plant produces a vast number of cross-fertilized vigorous

seeds, hence it is not surprising that is a very common plant, which by

its dense colonial growth can suffocate other plants, and form close

associations of the same species.

The colonies become less vigorous in the

course of a few years as few new seed plants can thrive in them, owing to

the fierce competition for space and light. The colonies are, therefore

perpetuated by the plants budded off from the old stems. This continued

vegetative reproduction result in decadence and the gradual invasion of

the colonies by more vigorous types.

Red Campion (Lychnis dioica)

Red is a very common colour among the woodland

plants, the Wood Geranium, the Dog Rose and Rose-bay all flaunting this

showy colour. The Red Campion, as its name implies, also rejoices in

bright, colored flowers.

Most red flowers are adapted to pollination by

butterflies. One might think if the nectar was so concealed that only

butterflies could reach it, when moths also could obtain it. To this, one

must point out that at night, when the moths are flying, red is invisible

and as red flowers are rarely scented, moths would not be attracted to

them, thus the butterflies have the field to themselves.

The Red Campion is quite a common plant in

shady, stony places, in woodland clearings, upon screes, and on the edges

of woods and thickets. It is quite hardy and may be found at over 3,000

feet in the Highlands.

It is a perennial, forming gay colonies which

make a beautiful picture in early summer. The rootstock is stout and

tough and gives rise to tall, branching, leafy stems. In winter the

plants are only visible through a few leaves crowning the summit of the

rootstock.

The lower leaves are opposite, egg-shaped and

dark green in colour, whilst the upper ones are also opposite but much

narrower. The leaves and the stems are covered by stiffish hairs which in

the upper part of the plant become very sticky and function as a defence

against creeping insects which may try to reach the flowers and steal

their abundant nectar. It is quite a common thing to find ants, small

beetles and flies trapped upon the sticky hairs to die miserably.

The flowers are arranged in a special type of

inflorescence known as a dischasial cyme. If we examine a plant we shall

find that the main stem seems to be terminated by a single flowers, two

branches carrying on well above it. Each branch is again terminated by a

flower and again gives rise to two branches which may be terminated by a

flower without further branches. This arrangement allows of a succession

of blooms over a long period.

Each flower is a beautiful structure and one

that must fill us with a sense of wonder at the marvels of Nature as

portrayed in common things.

The large, swollen, tubular calyx, which forms

a perfect protection to the corolla, is usually reddish in colour and

covered by viscid hairs and is crowned by five, narrow, pointed teeth.

The corolla is composed of five, free,

peculiarly-shaped petals whose lower portion consists of a narrow claw

with a membranous wing forming a tube about one inch deep within the

calyx. The upper portion or limb, which is heart-shaped and rose-colored

and at right angles to the claw, has an erect, double-fringed scale at its

base to prevent rain entering the tube and also small insects.

The plant consist of two types, one of which

produces male or staminate flowers only, the other female or pistillate

flowers only.

The staminate flowers are composed of two

rows of stamens arising from the base of the corolla tube and surrounding

a conical, greenish object which is an abortive ovary around the base of

which nectar is secreted. The outer row of stamens lengthens until the

anthers project beyond the corolla throat, and as soon as they have shed

their pollen, the second row lengths to take their place. A butterfly

visiting these flowers will be dusted with pollen over the face and upper

part of the proboscis.

The female flowers consist of a conical ovary

surrounded by ten tiny teeth which represent undeveloped stamens, and

surmounted by five long fine styles with a receptive stigmatic surface

upon the inner edges, whilst at the base of the ovary is situated the

nectary. The styles protrude beyond the corolla tube just where they will

receive pollen brought from a male plant.

The presence of abortive stamens and ovaries

shows that these flowers are descended from hermaphrodite ones and these

can sometimes be found if one searches a colony carefully.

The dioeciously arrangement makes

cross-pollination, imperative, but it also means that the risk of not

being pollinated at all exists. For this reason the flowers are produced

over a long period and remain open a considerable time.

The female flowers are followed by a large,

conical capsule after fertilization, which ,when ripe, splits open at the

summit by the ten teeth which remain erect, and then as the plant sways in

the wind, the seeds are jerked out to fall well away from the parent

plant.

In the Highlands, usually in low areas near

railways, cultivated land or roadsides, we may find a similar plant with

larger, pure white flowers. This is the White Campion (Lychnis alba),

which some believe to be a variety of the Red Campion. It is adapted to

moths and the flowers, which open in the evening, are pure white and

sweetly scented in order to attract these visitors. During the day the

white flowers are much less conspicuous and are then scentless, hence they

are little visited by day-flying insects, and the nectar is thus conserved

for its nocturnal benefactors. |