|

THE

SHRUBS AND TREES OF THE MIXED WOODS

As we

have already observed in the account of the Pine Forests, woods and

forests compose only a small proportion of the surface of the Highlands.

Of this area the amount under mixed woods is very small.

However,

woods containing oaks, birch, rowan and aspen occur in many parts of the

Highlands. In all the larger valleys and glens, as in the Tay valley, the

pass of Killiecrankie, the Trossachs and around Inverary, beautiful woods

occur, rivaling in variety and loveliness the woods of the more hospitable

south. Again, in the western Highlands, wherever shelter from the wind

and cold are obtainable, large stretches of mixed woods occur. In the

more exposed places thickets of birch take the place of the mixed woods

and may be encountered up to about 1,000 feet above sea level. Above this

level the birch woods give place to the pine and moorlands.

Beyond

this height the short season, the fierce winds, the severe frosts and the

acid soil mixed woods impossible.

In the

southern Highlands and in sheltered places in the western Highlands, the

oak is the most important tree. Elsewhere in the eastern and central

regions, as well as the far north, woods are much scarcer and are usually

composed of birch, which is also very common everywhere in the Highlands.

In the

following description I shall describe the various trees to be found in

the mixed woods of the Highlands and the various flowering plants which

flourish beneath their shade. I will commence with the oak.

The Oak (Quecus sessilifloria)

The oak

woods are very beautiful, but if one would see them at their best, one

should see the woods around Arisaig Bay and Beasdale in the far away

western Highlands.

It was

late October when I first visited this delectable region. I was a day of

brilliant sunshine, whilst the sky was pale azure blue. All around the

bay the beautiful oak woods came down to the scintillating sea, their

dying leaves a find golden brown, contrasting with the dark brown slopes

of the higher hills. The soft west wind gently rustled among the dry

leaves which seemed to whisper to one another as if they were mimicking

the waves that hissed upon the sandy shore.

As I sat

on the mossy roots of one of the oaks, I became aware of the real beauty

of these woods in all the splendour of the autumn. Rugged grey trunks and

gnarled branches dressed in russet brown; brave trunks that had survived a

thousand winter storms, the very emblems of strength and endurance.

Beneath, the mossy ground was covered with a crisp carpet of dying leaves

where the red squirrel was searching for the last acorns before commencing

his long winter sleep, and where the fairly-like roe-deer moved so gently

that one would think they were afraid to disturb the long sleep of the

withered leaves or the spirits that must inhabit this lovely spot.

As I

looked across the bay I saw the jagged peaks of Sky, silhouetted like a

row of shark’s teeth against the blue sky, and the strange peaks of Rum

peeped over the rugged headlands enclosing the bay.

Behind

me, beyond the low ridge, I saw the massive peak of Ben Nevis, over forty

miles away, standing out majestically against the eastern sky, its ancient

head and shoulders white with newly-fallen snow. It stood dark and

menacing as if King Winter had already taken up his residence there and

was regarding these lovely regions with his icy eyes, waiting for the day

when he could come down and claim them too.

The Oak (Quercus

Robur) is perhaps the most typically British of all trees and is in

many ways a very picturesque one. Its massive, rugged trunk and gnarled

mighty branches are unmistakable whether in mid-winter, when it stands

bare to the winds and rain, or in the full beauty of mid-summer.

It is a

beautiful tree, in its pale-green coat of springtime when its branches are

gaily decked with catkins, or in mid-summer when it is clothed in a deep

green coat of dense foliage, or in autumn when it has changed its somber

green for a beautiful russet-brown, or again in winter when one can see

its massive grandeur like that of a naked athlete.

The oak

of the Highlands is a slightly different species to the common oak of the

south and is know as Quercus sessiliflora.

Unlike

Quercus Robur, it will grown on light soils if not too shallow. For

this reason it is chiefly found in the valleys where it ascends the sides

until the soil becomes too thin for its requirements. Naturally, it

requires protection from fierce winds and extreme cold and this reason

limit’s the areas suitable to it growth in the Highlands.

Quercus sessiliflora is a straight trunked tree

with less spreading and less massive branches than the more common oak.

It is slow growing and lives to a great age. It may attain a height of

eighty or ninety feet in deep rich soil, but in the Highlands fifty feet

is about the maximum attained.

The

strong massive branches are covered in great numbers of crooked, gnarled

twigs and are thickly clothed with leaves which commence to break from the

buds about the beginning of May after the catkins have bloomed. They are

dark green above and oblong in shape with a very sinuate margin. They are

glabrous, the under surface being of a pale green. These leaves are

retained until the autumn, when they change to a deep brown and are

gradually shed as the autumn gales howl through the woods. The young

trees, however, usually retain the old brown leaves till the next spring.

The

flowers of the oak are of two kinds and are found separately upon the same

tree.

The male

flowers consists of catkins, which are about two inches in length and

several occur together.

The

female flowers are either solitary or several in a cluster and consist of

a perianth of green scales, within which is enclosed the ovary and the

three styles which project beyond the perianth ring.

The

flowers are wind pollinated, and for this reason they appear before the

leaves can hinder the passage of the pollen from the males.

The fruit

of the oak is the familiar shiny green acorn in its hard green cup. The

fruit of Quercus sessiliflora has no stalk, and this is the chief

structural difference between it and Quercus Robur.

My

readers who know something of the English countryside must all have

delightful memories of the Wild Cherry (Prunus Cerasus) in blossom

in the southern woodlands in May, and must have been charmed by the

snow-white masses of flowers and the delicate beauty of the individual

blooms. It is, I think, above all flowers the one which best portrays the

beauty of spring, fresh, pure and dainty in its chaste beauty, with its

reddish trunk surrounded by a sea of bluebells and shy primroses, while

the blackbird sings from the topmost branch his praises to the Creator of

all this loveliness.

In the

Highlands, unfortunately, the Wild Cherry is rare, and except in the

southern fringes is not even a native plant.

Its place

is taken, however, by another species, the Bird Cherry (Prunus Padus),

which is a lovely tree if less conspicuous than the wild cherry. Its

small clustered blooms make up for their lack of size by their delicate

fragrance, which, borne upon the air with the faint perfume of opening

birch, the aromatic odour of bog myrtle, and the mixed odour of the pine

and moss and mountain air, is the very embodiment of all that is so

delightful in this wild mountain country.

Perfumes

and odors bring back to the memory many places and incidents. Thus the

rich odour of burning peat will bring back memories of that little white

croft in Skye, nestling in the shadows of the Coolins, where one spent a

never-to-be-forgotten holiday; if I but smell the sweet briar I am

transported to the smooth rolling downs of the south, and the honey scent

of heather brings back the delightful days I passed in the Cairngorms

whilst rambling over their empurpled sides.

So with

the Bird Cherry. It brings back memories of spring in Speyside, of pale

green birches sparkling with rain drops, of the murmur of rushing burns,

their sides golden with marsh marigolds and beautified by the innocent

blooms of the cuckoo flower and the bird cherry itself. Its pale flowers

star the woodsy edges of roadsides and streams, and its perfume tempts the

passer-by to pluck the sprays of its fragile blooms to return with them to

his apartment, where its subtle perfume will keep fresh his springtime

memories.

The Bird

Cherry never forms a large tree as the Wild Cherry does, and is usually a

large, spreading shrub of from eight to ten feet in height, although in

sheltered spots it may attain to the dignity of small tree.

The

leaves are usually oval in shape with a very finely-toothed border, and

are smooth and shiny on the upper surface.

The

flowers, which are rather small, are conspicuous not only by their sweet

perfume, but also because they are arranged in close, long racemes which

may be as much as six inches in length and contain many flowers. These

racemes are produced on short leafy branches.

The

flower is constructed on the usual rose plan, with a central receptacle

from which springs a single carpel (usually several in Rose Family). From

the sides of the receptable arise the many stamens and five creamy white

petals. Nectar is secreted in a ring around the receptacle. The stigma

is mature before the anthers so that cross-pollination will take place

when insects arrive from old flowers to the newly-opened ones. But as the

stigma remains mature after the anthers have opened, self-fertilization

will take place if cross-pollination has not already been arrived at. Thus

the flowers are always certain to set seed.

After

fertilization the corolla fades and the ovary swells to form a small,

round, black fruit which contains a very hard, rugged stone containing the

seed. These small cherries, although very bitter, are much eaten by birds

and thus the seeds are dropped at a distance form the parent plant.

The Birch (Betula alba) The Birch (Betula alba)

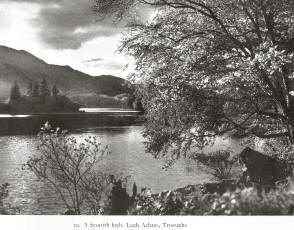

If one

was asked what was the loveliest tree in Britain I am sure many would

reply the birch. This dainty tree, often no more than a large shrub, is

one of Nature’s masterpieces. Beautiful specimens are to be found in the

lovely woods of the Trossachs. I have memories of idle summer days on the

sylvan shores of Loch Achray where, lying on the mossy turf, I have

dreamily watched the branches of the birch curving gracefully down to the

water’s surface and gently agitating it like fairy fingers, its thin

leaves whispering softly as if they also were afraid to break the

tranquility.

No

Scottish scene would be complete without the birch. Not for it the

sheltered valleys and lowlands, but the rugged hillsides and the wild

glens, where we may find it struggling with the elements, precariously

rooted on the face of steep precipices and crags; beside thundering

waterfalls and raging torrents, by mountain tarns and on wind-swept moors,

it reigns supreme.

To find

it at its most beautiful, however, we must wander among the relics of the

Old Caledonian Forest. Magnificent trees may be found by lonely Loch

Tulla. Their silver trunks gleam bright in the sun in vivid contrast to

the black pines, and nothing more graceful than their drooping branches

can be imagined. Autumn by Loch Tulla is unbelievable, the pines with

their black leaves and red branches, the silver of the birch and the amber

of their leaves, the bronzes, yellows and oranges of the ferns, and the

blue of the loch and sky combine to make s symphony in colour.

It is

beautiful at all seasons. In winter the twigs of a birch wood give the

impressions of a purple mist hanging over the hillside; in spring the

bright freshness of its leavs and their delicate fragrance are not matched

by any other tree; in summer after rain, when every leaf holds an

iridescent crystal at its tip, it is the real ‘Lady of the Wood’; in

autumn its fallen leaves give brightness and beauty to the scene and

alleviate the feeling of sadness an autumn wood always engenders.

The birch

is found at higher elevations than any other tree in the Highlands, often

reaching 3,000 feet. It forms broken thickets on the steep, craggy sides

of the glens, open scrubby woods upon the sandy moraines of Speyside, and

pure woods in many parts of the Highlands, especially in the more exposed

and elevated parts of the valleys where the strength of the wind precludes

any other trees.

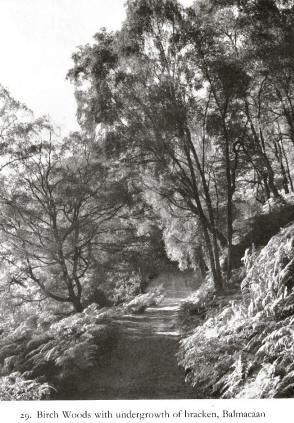

A birch

wood is not a dark or gloomy place, as is a beech wood in summer. Its

small, thin leaves give little shade, and as the trees rarely grow

thickly, there is usually a well-developed undergrowth. Bracken, heather

and brambles cover the ground, whilst the beautiful mountain ash often

bears it company. The Wood Amemone, Chickweed Winter-green and Wood

Geranium are often found in these woods, as are the Dog Violet and

Cow-wheat.

It rarely

attains more than eighty feet, and at its highest range is often no more

than two feet in height. Its trunk is slender and covered by the

characteristic silvery bark. The lower part of the trunk is usually

fissured and grey, but higher up the bark is smooth, thick and tough, and

of a beautiful, clear white; its toughness is shown by the fact that in

fallen trunks the wood may be reduced to power contained in a cylinder of

bark.

The trunk

branches toward the summit and ramifies to form a large number of slender,

very wiry twigs which droop towards the extremity. They are perfectly

adapted to withstand gales and fierce gusts of wind.

The

branches are thickly covered by small, thin, triangular leaves which are

of a tough consistency and quite smooth above. Owing to their thin

texture they form little humus.

The

flowers, as in the case of the oak, are produced in catkins. The male and

the female catkins are both found on the same plant at the extremities of

the branches. The males are pendulous and light green in colour, but

become reddish on opening in April. The females are erect and much

smaller, but are often produced on the same twigs as the males. Seven

tiny flowers are covered by a tiny scale. Each pistil produces two

delicate styles that stick upright and project beyond the scale.

The

flowers are wind pollinated. They mature when the leaves are fully out,

but this does not hinder the passage of the pollen as the leaves are so

small.

After

fertilization the female catkins form little cone-like bodies, each flower

producing a tiny nut. Each nut has a pair of tiny, brown wings, and in

late summer they fly for considerable distances from the parent plant.

For this reason, if protected from grazing animals, the birch will

continually increase its territory and as it is very hardy it can compete

against all comers. It is also very quick growing and is able to

consolidate its newly-won positions in a remarkably short time. For this

reason, land not fit for agriculture is soon invaded, and if not cleared

becomes a typical birch wood community.

In many

parts of Scotland, especially in the northern Highlands, the birch woods

are a perfectly matured association with their own particular fauna as

well as flora. Some of these woods may well be the most ancient flora of

these islands.

We have

actually two species of birch tree in Britain, the Silver Birch (B.

alba) and the Hairy Birch (B. pubescens). The latter is the

common birch of the Scottish woodlands and grows on more acid soil than

the former. The silver birch, however, is frequent in most parts of the

Highlands and so is often confused.

In B.

alba the leaves are smooth, whilst the young branches hang gracefully

and, although devoid of hairs, are often warty in appearance. The fruit

also helps to distinguish it, the wing being twice as wide as the seed.

In B.

pubescens the leaves are usually hairy, the young twigs are erect and

downy, whilst the seed wing is hardly wider than the seed.

Mountain Ash (Pyrus Aucuparia)

The

Mountain Ash, or Rowan, as it is called in Scotland, is one our most

handsome trees. It is a glorious sight in May with its large, shapely,

pinnate leaves and large panicles of creamy-white flowers, which often

almost conceal its foliage. In the autumn its masses of bright, orange-red

berries, shading to scarlet, make it a striking and very ornamental part

of the landscape.

It is a

tree of broken precipices and wild rocky hillsides, where it struggles

upwards at many strange angles, its roots pushing deep down into the rock

crevices and anchoring it securely against the winter gales. It is in

these places the Rowan is to be seen at its best. It is also frequent in

the forests and woods. In young woods it grows quickly, but once it

attains the height of fifteen to thirty feet in grows but little, and on

being overtopped and overshadowed by other trees, it seems to give up the

life struggle and gradually disappears from the flora.

On the

rocky hillsides, however, there are few or no tree high enough to overtop

it, indeed few except the birch even to compete with it and so, where

sheltered from too much exposure to the wind, it attains its finest

development.

The trunk

is usually straight and branches at the middle to give the tree a very

bushy appearance.

The

leaves are very beautiful, and remind one forcibly of those of the Common

Ash which, however, belongs to a different family. Each leaf is a large

structure and consists of six or seven pairs of leaflets and an odd,

terminal one. Each leaflet has a very short stalk, is oblong in form, and

its margin is serrate, ie. toothed like a saw. They are smooth above, but

the lower surface is covered by a grayish down. These graceful leaves, by

being cut up into many leaflets, offer less resistance to strong winds

than a large, simple leaf would do. For this reason trees which usually

grow in exposed situations have small leaves, e.g. birch, conifers and

aspen.

The

flowers are displayed in dense, branched corymbs at the extremity of the

branches. They are produced in such profusion that the tree appears to be

a mass of bloom in May, the leaves being almost hidden.

Each

flower is a miniature rose in form. The cup-shaped calyx is covered in

grayish down and adheres completely to the ovary, its five loves

alternating with the creamy-white petals. The stamens are numerous and

form a ring around the three spreading styles.

The

flowers produce a very sweet, almost sickly perfume which attracts myriads

of honey -bees to partake of the abundant nectar secreted at the base of

the calyx cup.

After

fertilization the calyx and ovary swell and become fleshy, to form a

rounded, orange-scarlet berry, or rather a pome, which is constructed in a

similar fashion to that of the apple. In this plant both calyx and ovary

share n the formation of the fruit.

The ripe

berries are greedily devoured by thrushes and blackbirds. The seeds pass

through the birds without damage, the birds’ digestive juices actually

aiding germination by softening the hard seed-coat.

This is

very efficient manner of seed distribution as the birds may fly a long

distance from the parent tree before dropping the seeds. It must be

remembered also that the seed is dropped along with other waste matter

which it can use whilst a seedling. It thus get a good send off on its

life struggle.

Aspen (Populus tremula)

This is

another common tree in Highland woods and is a member of the Poplar tribe

which is included in the Willow Family. It may be found up to 1,600 feet

in the Highlands and is thus quite a hardy tree. It rarely forms a pure

wood, but is found scattered among the other forest denizens.

It does

not attain a very great size. Its root system is rather extensive, but

the roots do not descend very deeply into the soil. For this reason it

sis more common on damp soils where there is little risk from drought.

The roots send up large numbers of suckers which form thickets around the

base of the tree. These scarcely develop in the woodlands as they are in

the shadow of other trees. In more open situations, however, they form a

ring of vegetation around the tree and may develop into tress themselves.

The Aspen

is remarkable for its peculiar, restless foliage which seems to be in a

state of perpetual motion, even on the calmest day in summer. The old

Highlanders believed this was so because of the Cross of Calvary was made

from aspen woods and for this reason it leaves can never rest.

The

reason for this restlessness is due to the fact that the long leaf stalk

is compressed vertically in its upper part and is hence too weak to keep

the leaf in a horizontal position, thus the slightest breeze is enough to

put it in motion.

The

leaves are small and rounded in form, of a thin texture, and with a

toothed margin. They are deep green above, but almost silvery beneath

although they are completely smooth. As they tremble in the wind, the

alternation of dark and light surfaces gives a very strange and yet

beautiful effect, which is accentuated when the tree is seen against the

dark foliage of a pine corpse, or against the background of black clouds

preceding a thunderstorm in summer.

The

flowers of the Aspen like those of the Sallow are produced before the

leaves. To find them we must visit the tree in early April in the

Highlands. The tree will then be seen to be covered by large, wolly

catkins which look, for all the world, like large, hairy caterpillars.

The male catkins are produced on different trees from the females.

The

flowers are constructed similarly to those of the Willow, but the scales

are deeply divided and are covered with long, brownish hairs. The catkins

differ from those of the Willow in the fact that they are always pendant.

This is because they are completely dependent on the wind for pollination

and in their hanging position can take full advantage of the wind, and as

they sway the pollen is shaken out of the anthers and transported in a

cloud to the female catkins. The male flowers each have seven or eight

stamens as against one or two in the Willow. This is because the wind

pollination must be produced to make pollination more certain. Fort his

reason also the stigmas are much larger than in the Willow.

After

fertilization the ovary forms a green capsule in which many seeds are

produced. From each seed arises a tuft of long, silky hairs. In the

summer of the capsules open and hosts of silky seeds fly away long

distances upon the breeze, to fall far from the parent plant.

This tree

is thus dependent on the wind for its existence, as without it, its

flowers could not be pollinated and its seed could not be distributed. |