|

The

Scottish Highlands as a whole do not support a very large amount of

forest, and much of what there is, is not native forest, but has been

planted by man. Fairly extensive areas of mixed woods occur in the west

as at Beasdale in Morar, and in most of the glens of the Southern

Highlands, but extensive woodlands are the exception in this great

highland area.

However,

we find in the Highlands one of the largest areas of forest in Britain.

This, the great pine forest of Rothniemurchus is over twenty miles in

length and three to seven miles in width, covering the whole of the floor

of the Spey Valley between the Cairngorms and Aviemore and stretching more

brokenly beyond that to Kingussie and Boat of Garten. Much of this great

forest has been felled, much has been planted by man, but large areas of

native forest exist to show us what the forest was like in its ancient

grandeur.

The Scots

pine is to be found in smaller groups on the edge of the Moor of Rannoch

between Tyndrum and Bridge of Orchy and around Loch Tulla. It is t be

found again in Deeside, where some of the oldest pine in Britain area to

be found. Most of the glens have scattered patches of pine in their lower

stretches.

I am not

going to describe the many great plantations of pine and spruce to be

found in many corners of the Highlands, for most of them are of recent

origin and do not possess the associated plants to be found in the old

established forests.

Most of

my descriptions of the pine forest and its associates will be of

Rothiemurchus Forest, which if the finest pine forest to be found in the

Highlands and contains many interesting plants which are only to be found

beneath the shade of its ancient trees.

I have

many delightful memories of Rothiemurchus, and the sough of the wind in

the dark leaves of its pines is always with me. No one who has wandered

amid the noble trees of this forest could feel anything else but a sense

of uplift in its magnificent setting. Nestling into the bosom of the

noble Cairngorms whose grand skyline shows up magnificently in a framework

of pines, this forest is full of hidden lochs, of noisy mountain torrents

and of quiet glades where the roe-deer pass like phantoms among the red

trunks of the trees.

In early

June the hot sun brings out the perfume of the pines, a

never-to-be-forgotten, delightful odour that one wishes to pull into the

lungs along with the sparkling mountain air. The gnarled and twisted

pines growing out of every precipice and bank look like the bodies of

tortured giants, their shaggy head still held aloft in proud defiance.

Peace, a deep and soul-easing peace, is here. A mountain torrent babbles

eternally among it rocks and secret pools, a curlew pipes mournfully from

a distant bog and the wind soughs in the pine needles like the sea on some

forgotten strand, hissing gently as it caresses the sand. Beyond that,

silence, deep uncanny silence, as if one were in the presence of God and

in the presence of the centuries which these great trees span.

And as

one reflects, one thinks of those huge forgotten forests that for all but

their roots have disappeared from the face of the hills. The lost forest

of Rannoch; what titanic disaster uprooted and destroyed this huge pine

forest and turned its pleasant glades into a wilderness of bog and stone

where death awaits the unwary and the winter gales how with unbroken

ferocity? In every glen and valley we find the stumps and roots of

ancient pines. Departed probably as are the men that felled them or the

fires that destroyed them, departed, never to return.

And as I

recline on an uprooted giant in this secluded corner, the setting sun

throws vast shadows across the forest. A silence even more profound seems

to grip the trees, as if all Nature waited in awed silence for the night.

Beyond, the Cairngorms are bathed in an ethereal pink glow; dusk descends

on the forest, but for more than half an hour that pink glow remains as if

the sun were loath to quit the corries and deep glens. At last the faint

glow leaves the highest peak of Cairngorm and the twilight falls. An owl

commences to hoot among the dim pines and I realize that I must be off,

for many a man has been lost as night fell in this labyrinth of trees and

paths, and the spectre of the Bloody Hand is still supposed to wait for

those who are lost after nightfall in this black forest.

With

Rothiemurchus forest are associated some of the most delightful spots in

Scotland. How much the pines have contributed to this! What would

Loch-an-Eilean be without its encircling mantle of pines?

This

jewel of the Highlands lying among the black pines like a diamond on black

velvet, where in Britain shall we match its beauty? Loch Morlich, Glen

Feshie and Loch Garten, what would they be without the pine trees which

soften their otherwise barren shores and the rock-strewn wastes around

them? We have our answer in upper Glen Einich and Loch Avon, whose stark

somber grandeur cannot be matched elsewhere in Britain. What a difference

the pines which once clothed upper Glen Einich would make! How they would

soften its grimness!

And now

that we have described the beauty and charm of the pine forest let us

study the reasons why these trees flourish in these places. Let us study

the individual tree and see how it is fitted to the land it has chosen for

its own, and how it differs from other plants in its leaves, flowers and

seeds.

And

lastly, let us study the lowly shrubs and flowering plants that are

associated almost exclusively with the pines and are rarely found beyond

their shade.

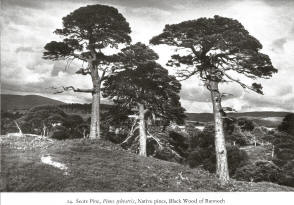

Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris) Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris)

The Scots

Pine flourished on soil which is always well drained, as it cannot stand

water-logged soil around its roots. Debris washed down from ancient

moraines and consisting mainly of sand and pebbles makes an ideal soil for

this tree and, for this reason, it flourished exceedingly well in glacial

debris of the Spey Valley. Similar conditions exist on the Rannoch Moor

area and in Upper Deeside. It also grows on steep hillsides, especially

those of a granite nature, its roots penetrating into the cracks and

crevices of the rock in order to find a safe anchorage. These trees are

often contorted into queer shapes.

The Scots

Pine has deep-striking roots which penetrate to the moister layers beneath

the surface. It will face conditions of drought without fear and

flourishes on soil that is practically sterile. It also produces many

horizontal spreading roots which ramify in the surface soil, rich in

humus.

We do not

find the Scots Pine at very great altitudes in the Highlands. In the

Rothiemurchus area on the north-western face of the Cairnogrms the limit

of the pine is 1,750 feet. Above this limit there are no pines. On the

fringe of this frontier area the pine is very dwarfed and stunted,

sometimes of an espalier growth. On southerly slopes the limit is

somewhat higher.

The

reason for this upward limitation is to be found in the force of the wind,

the intensity of the cold and the shortness of the growing season. This

upward limit is very important for it marks the frontier between the

lowlands and sub-alpine regions and the real alpine regions.

The Scot

Pines is easily recognized from other conifers by its reddish coloured

bark and by the fact that it usually only has branches near the summit of

the trunk, the lower ones dying off as the tree grows. The crown of

branches has a somewhat shaggy appearance, and this, with the rugged

grandeur of the trunk, makes the tree blend magnificently with its wild

surroundings.

When

growing in exposed or rocky places the Scots Pine often branches near the

base and the trunks may be greatly contorted. It attains a height of 100

feet in the sheltered valley of Speyside, but it is little more than a

shrub at its highest limit.

The pine

is different in many respects from other plants. We must remember that it

is a member of the group of plants call Gymnosperms, which was well

established millions of years before the trees and plants with which we

are familiar today, and it still retains many primitive features.

The

leaves are peculiar in being borne on short deciduous shoots, known as

’dwarf shoots’. Two leaves are produced on each of these very short

branches. They live for several years but are eventually shed, and when

this happens not only the leaves but the ’dwarf shoot’ also is lost. The

leaf is thick and needle-like in form with one flat face and one rounded

one, and possesses a very thick, leathery epidermis which prevents excess

transpiration. The stomata are deeply sunk in the epidermis to the same

end.

The

needle-like leaves expose a small surface to the wind and give little

surface to which the snow can cling in winter-time.

The

flowers of the Scots Pine are very different from those of other plants.

It would require a very long and technical description to show how their

flowers differ from those of ordinary plants. Suffice it to say that the

females flowers possess no style or stigma and no ovary, the ovules being

quite unprotected by an outer covering, whilst the stamens consist of

anthers only , produced on the under side of a sale. This shows us that

the pine belongs to a much more ancient flora than our other much further

advanced flowers and trees with their complicated arrangements of petals

and sepals, stigmas and ovaries and colour and perfume. The ancient

world, before the evolution of the bees, must have been a grim and

dreadful place where flowers with their beautiful colours and perfumes had

not yet arrived.

The

flowers are wind pollinated and on a dry sunny day in spring the pollen

drifts in golden clouds among the somber trees. The pollen grains possess

two bladders which act as wings and are beautiful objects under the

microscope. These aid the pollen in its journey from the stamens to the

female catkins.

After

pollination, the female catkin becomes woody and forms the familiar pine

cone consisting of hardened scales arranged like the tiles on the roof.

Each scale covers two winged seeds. These cones hang on the tree till the

following year, when on dry sunny days the scales open and the winged

seeds fly away, often to considerable distances from the parent plant.

The Scots

Pine is the only indigenous pine in Britain and is only native in the

Scottish Highlands. Other conifers such as Spruce, Silver Fir and Larch,

although often forming extensive plantations in the Highlands, are

planted, these trees not being native to any part of Britain.

The pine

forests and woods of the Highlands are the home of many interesting plants

which are either only found beneath the shade of the pines, or, if not

entirely associated with them, are at least typical of these black

forests.

They

include the beautiful Pyrolas, of which all the British species are found

in our northern forest; the Orchid (Foodyera repens), which is

peculiar to the Rothiemurchus area and (Corallorhiza trifida), a

strange saprophytic orchid found very rarely in the pine woods of the

eastern Highlands; and the two shrubby plants Whortleberry (Vaccinium

Myrtillus) and Juniper (Juniperus communis).

Other

plants such as the Yellow Cow-wheat, the Red Bearberry, etc., are found in

the pine woods, but they are just as common on the moors or in other types

of woodland and so have been described under their appropriate headings.

Juniper (Juniperus communis) Juniper (Juniperus communis)

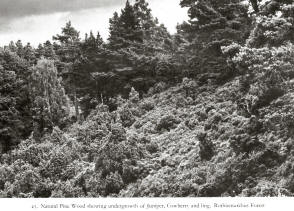

Under the

shade of the black pines we do not find the dense undergrowth of the mixed

woods. For one thing the amount of shade is greater, and secondly many

plants cannot live on the humus formed by the pine needles.

One of

the large plants that thrives among the pines if the Common Juniper. This

shrub or small tree, usually two to five feet tall, but sometimes

attaining twenty feet, is, like the pine, a conifer. It thrives on dry

soil, being like the pine a xerophyte. It is very bushy and much branched

and is clothed with a dense, evergreen foliage. The leaves themselves are

in whorls of three and are like fine, short needles, ending in a prickly

point. They are bright green on the under surface, but are glaucous and

of a blue-green above, so that when viewed from a distance the plant has a

grayish appearance.

The

Juniper is also a Gymnosperm and its flowers, as in the pine, are of

peculiar character. Both male and female flowers are found on the same

plant; the females consist of three to six fleshy scales surrounding the

naked ovule and forming a rudimentary carpel; the males consist of broad,

shield-shaped scales containing three to six anthers and arranged in small

catkins. As in the case of the pine, the flowers are wind pollinated.

The wood, leaves and branches have a sweet resinous odour.

After

pollination the female flowers form globular, dark purple-blue berries

which are greedily eaten by such birds as black-cock, grouse and

capercaillie.

Whortleberry (Vaccinium Myrtillus)

My first

acquaintance with this lowly shrub was among the pine woods and heaths of

Surrey, where I spent some of my happiest boyhood days, and I have many

happy memories of halcyon days in July and August among the purple

heather, as I helped to fill the purple-stained baskets with the luscious

purple-black fruit of this prolific plant.

It is a

far cry from the balmy hills of Surrey to the bracing northern forest of

Inverness-shire where we find the Whortleberry as abundant under the pines

as on the southern heathlands. Its fruit in the north is much finer

flavoured than in the south.

The

Whortleberry is a small glabrous shrub which barely exceeds six inches to

one foot in height. Its roots are creeping and send up a tough woody

stock which is covered in green, slender branches, which are quite sharply

angular. They produce very thin ovate leaves, which are shed each autumn;

at this time the pine woods exhibit a magnificent picture. The leaves

fade to a bright reddish-yellow and form a carpet of brilliant hue beneath

the sombre trees.

The

flowers are in bloom in early spring, about April or May, and are not very

conspicuous, being like small globular bells which are greenish at the to

shading into white, the edge of the mouth being tinged with red.

These

flowers are very interesting structures and their manner of pollination,

which is the same with small modifications as in the other species of

Vaccinium, is well worth studying.

Each

little bell contains a pistil consisting of a long style, which is

surmounted by a round stigma which projects from the mouth of the bell.

Each stamen commences at the base of the bell and its style is a flattened

stalk which is surmounted by two flagon-shaped structures, which are in

effect two half-anthers. Behind each of them are two horn-like

structures, each of which has a pore-like opening. When a bee visit’s the

flower, it grips the smooth bell by its slightly recurved rim and its body

comes in contact with the stigma which matures before the stamens. It

leaves any pollen obtained from an older flower on the stigma, thus

pollinating the flower. On going to an older flower, the bee pushed its

tongue between the stamens in order to reach the nectar secreted at their

base. Its head touches the horns on the back of the anthers and the

pollen is jerked out over the bee.

After

fertilization the flower fades and a green berry takes its place. By

August the berry is the purple-blue fruit covered with bloom which we love

in our preserves and is so greedily eaten by the forest birds.

The Wintergreens (Pyrola)

The

Highlands are rich in members of the Heath Family for besides the three

common heaths, we have the Whortleberries, the Bearberries, the Menziesia,

the Trailing Azalea and five Wintergreens, so we can see that this family

is certainly very successful in our mountains.

The

Wintergreens contain five beautiful British species all of which are to be

found among the pines of Rothiemurchus.

It was a

glorious July afternoon when I first made my acquaintance with this

lovely genus. The morning had been wet, but the clouds had parted, and

from a brilliant blue, rain-washed sky the un shone down with added

splendour. Large, white, woolly clouds sailed across the sky like great

galleons, bringing out in fine relief the majestic outline of the

Cairngorms.

Below in

the forest the rain drops dripped from the pine needles, and that

delightful aroma of deep earth and vegetation, augmented by the hot sun,

mad the forest more beautiful than ever. In grassy glades, where each

blade of grass was adorned by rainbow-coloured drops of water, the

brilliant blue flowers of the field gentian shone like jewels.

Suddenly

among the Whortleberries, heaths and mosses below a great pine, I saw w

white spike of flowers which from a distance looked like the

lily-of-the-valley. I pushed my way through the wet undergrowth and on

arriving at the place where I had seen this strange plant I found that it

was a beautiful Wintergreen, its tall stem adorned with a spike of little

white, bell-like flowers, shading to pink near the base. Closer

examination proved it to be the Lesser Wintergreen (Pyrola minor).

The

Lesser Wintergreen has a tough, almost woody underground stem from which

arise one or two tufts of ovate leaves. These are three to four leaves in

each tuft and these are on very long stalks. They are thick and shiny on

the upper surface and a few usually exist throughout the winter. In late

spring the tufts send up a long naked stalk which sometimes has one or two

small scales near the top. This stalk produces a spike of several white

flowers, each of which hangs downwards like a small bell and has a small

bract at the base of its fragile stalk. It is a bell-shaped structure,

but the petals are not united as in most bell-shaped flowers, and they

curve inwards at the tips to close over the stamens. They are a beautiful

smooth white, delicately tinged with pale rose-pink. In this species the

style is longer than the stamens which are enclosed in the corolla.

The

pollination of this flower occurs in a very interesting manner. The

stalks of the stamens are bent backwards in the form of an S, and are in a

state of tension like a bent spring, being kept in position by the

petals. The opening of the anthers at this time faces downwards, towards

the base of the bell. When a bee arrives at a flower, It grips the

slightly recurved rim of the bell with its feet, and pushes its tongue

among the stamens to reach the nectar-secreted by the nectaries at their

base. This releases the stamens, which uncurl and throw their pollen over

the face and head of the bee. On going to another flower it leaves some

pollen on the projecting stigma. Bees and flies also arrive for the

pollen only.

Round-leaved Wintergreen (Pyrola rotund folia) Round-leaved Wintergreen (Pyrola rotund folia)

In

Rothiemurchus we can also find, quite frequently, the beautiful

Round-leaved Wintergreen (P. rotund folia) and its variety P.

media. It has fewer and larger flowers than P. minor, being

larger in all its parts. It is an exquisitely beautiful flower which

looks as though carved in ivory. It differ also in the length of its

style, but otherwise is much like P. minor.

The

One-sided Wintergreen (P. secunda) is another plant which is

comparatively rare in Britain, but is frequently found in the

Rothiemurchus area. Its habit is rather different, the stock being more

woody and creeping and sending up many leafy shoots. The leaves are thin

and finely toothed, being oval in shape and not round as in the other

species. The flowers are arranged in one-sided spike and are small and of

a greenish-white. It Is found at higher elevations than the other species

and is much rarer.

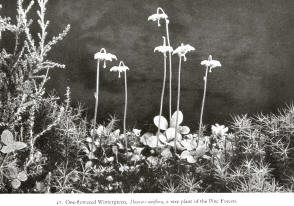

One-flowered Wintergreen (Moneses uniform) One-flowered Wintergreen (Moneses uniform)

The

remaining species, the One-flowered Wintergreen (Moneses uniform)

as beautiful and dainty a flower as one can find in Britain.

I know a

spot in a deep, secluded glen in the Cairngorms where a wild torrent roars

ceaselessly over its boulder-strewn bed, and a fine spray caresses the

feathery ferns which retain their vernal freshness almost into the

autumn. No path disturbs the tranquility of this delightful spot, where

only the roe-deer brushes the dew-drops from the bracken, as it slips like

a phantom between the trunks of the pines. Hidden deep in a mossy dell at

the foot of a shattered precipice, one can find a small natural grotto

among the fallen rocks and here nestling in the damp moss is a colony of

this delightful wintergreen.

This is

one of our rarest British plants and one can only find it in a few

secluded spots in the pine forests of Inverness-shire and Aberdeen-shire,

where it conceals its fresh loveliness like a beautiful nun who hides from

the world behind the convent walls.

It is the

almost wood stock of the other species, while the leaves are thick and

shiny like those of Pyrola minor. It send up a flower stalk

surmounted by a single, very beautiful, blossom.

It is of

pure white and unlike the other species is not bell-shaped, the petals

spreading. The stamens are not kept in position by petals, but their

stalks are spring-like and on being visited by an insect they dust it with

pollen as in the case of the other species. It does not produce any

honey, hence it has not adopted the bell-shape which is a device to keep

the nectar for long-tongued bees. It is visited by pollen-collecting bees

such as the masons and by flies.

ORCHIDS OF THE PINE FORESTS

The great

forest of Rothiemurchus contains yet another flower which is peculiar to

its particular area. This is the Creeping Goodyear (Goodyera repens),

a member of the aristocratic family of plants, the Orchidaceate,

the only member of the family to be found in the Rothiemurchus forest. In

certain remote pine woods of the eastern Cairngorms and Highlands we can

also find the Coralroot (Corallorhiza trifida), a saprophytic

orchid. The Highlands are rich in orchids, but these two rare species are

the only ones to be found in the pine forests.

Creeping Goodyear (Goodyera repens) Creeping Goodyear (Goodyera repens)

This

orchid is very common in the Rothiemurchus and other forests of Speyside,

but is very rarely found beyond the valley of that river. In many places

countless numbers of this little plant carpet the ground beneath the

pines, often being the only plant to be found among the pine needles. The

reason for this will be given later.

It has a

shortly creeping rootstock which sends up a single stalk to a height of

six inches to one foot. Near the base are a few thin, ovate leaves. The

flowers are arranged in a one-sided spike and are inconspicuous and of a

greenish-yellow colour. Each one grows in the axil of a small, greenish

bract.

The

fertilization of these flowers like that of all orchids is very

interesting and is a marvelous insight into the inner workings of plant

life. I will endeavour to describe it In an ensuing chapter dealing with

our other Highland orchids (see Chapter XIX).

Coralroot (Coralorhiza trifida)

To find

this strange plant we must search for it in certain remote pine woods of

the eastern Highlands. It is a very interesting plant for, unlike the

other plants that we have met, it is a saphrophyte, ie. a plant that lives

on decaying vegetable matter like a fungus.

I know a

secluded glen not far from Glen Clova where a colony of pines clings to

the steep hillsides and fills the head of the deep valley. Here is the

darkest corner, where the light seldom penetrates, it a family of

Coralroots. They stand among the gnarled roots of the pine like ghosts,

for in their stems and bract-like leaves there is no colour. Pale,

brownish-white or pale yellow, they are more like fungi than flowering

plants and a closer study of an individual plant will show us why they are

so different to ordinary plants.

In the

vegetable world most plants obtain their nourishment by means of their

roots and leaves. The roots, especially the fine hairy rootlets, absorb

the salts held in solution in the moist soil (ie. nitrates, phosphates,

etc.) The leaves, with the aid of the chlorophyll contained in

specialized cells, absorb by day the carbon-dioxide of the air to form

carbo-hydrates (ie. starch and sugar). These are stored by the plant to

be used as it grows. When in autumn the leaves fall to the ground they

contain some of the stored-up carbo-hydrates.

The plant

world, however, contains plants known as saprophytes which have given up

this way of living. The Coralroot belongs to this section.

It lives

on the nutriment contained in fallen leaves and dead mosses, and as these

contain the ready-made products required by plants it follows that leaves

and roots as possessed by them are not required; but it cannot make use of

this foodstuff directly.

It has

got over this difficulty as follows. In this plant we meet the phenomenon

of symbiosis, ie. the combination of two organisms to the mutual benefit

of each other. A kind of fungus, know as a mycorrhiza, lives n the outer

tissues of the rootlets. This fungus absorbs nutriment from the

surrounding decaying vegetable matter, making it available to the orchid.

At the same time the fungus obtains nutriment such as carbo-hydrates from

the plant. Without this fungus the very seeds of the orchid cannot

germinate. This amazing interdependence of plants and fungi is common in

the plant world, especially in those living in soil containing much humus.

The pyrolas, heathers, the pine and goodyera all above their own

mycorrhiza.

Above

ground we find that the plant has no chlorophyll and is of a yellowish

colour. It has no leaves, these being reduced to thin scale-like bracts.

Thus,

this plant, like all other saprophytes, and their cousins, the parasites,

who have given up an honest way of life and stoop to theft and easy

methods to obtain a living, is branded by the loss of its leaves, its

colour and its roots.

Even its

flowers are inconspicuous and devoid of beauty when compared with other

orchids. They are of greenish-yellow colour and form a loose spike of

five or six flowers, each one being contained by a scale-like bract.

|