|

Before

leaving the mountain pastures we must mention a further type of plant

which may often be found in rocky places or beside springs and rivulets.

Whilst tramping across the higher slopes of the Highland mountains, one

must have been often struck by the frequency with which one comes across

plant that are usually associated with the sea-shore and maritime cliffs.

Such plants as the Thrift (Statice maritime), the Seaside Plantain

(Plantago maritime), the Scurvy-grass (Colchlearia officinalis),

the Seam Campion (Silene maritime) and the Roseroot (Sedum

Rhodiola) are quite common plants in the mountain pastures and yet

they are all sea-shore plants.

To the

casual observer it must seem rather anomalous to find plants of such low

situations growing on these high exposed places. But, if we consider for

a moment the conditions affecting plant life in maritime situations, we

shall soon see that there are many points of similarity with conditions on

the mountain sides.

In the

first place, the maritime plants live under very arid conditions. The

soil is highly impregnated with salt and so the roots must rely on any

fresh rain water that may fall, as excess of salty water is as dangerous

to plant life as it is to animal life. Thus in dry weather the plants,

unless they had special water conserving adaptations, would be doomed to

extinction.

Their

only choice of habitat is the dry sandy shore or crevices in the rocks

beyond high-water mark. Thus maritime plants are adapted to combat

conditions of exceptional dryness.

Again,

there is little shelter from the wind and sun which beats down

mercilessly, and as the air is usually clear near the sea, radiation is

much greater, as is also illumination, which results in an accentuation of

the difficulties of plant life. As we have already shown, these

conditions are very similar to those in the high mountains.

To combat

these difficulties, the plants have developed thick, fleshy leaves with

specialized water conserving cells and a thick, leathery skin which

reduces transpiration to a minimum. They have usually a low, often

densely tufted structure as additional protection against the fierce

winds. These adaptations are, of course, similar to those adopted by many

alpine plants. It is thus nothing unusual for maritime plants to be able

to support themselves at high altitudes.

Naturally, on may say that is all very well, but how have these plants

journeyed from the sea-shore to mountain tops? They cannot walk or fly

there. The answer to this is that the seeds of these plants were conveyed

by the sea-birds which one so often sees on the high mountains. These

birds feeding along the sea-shore pick up the seeds along with mud in

their webbed feet. On flying to the mountain slopes they take these seeds

with them to be deposited wherever they alight. Thus have maritime plants

attained the elevated mountain slopes.

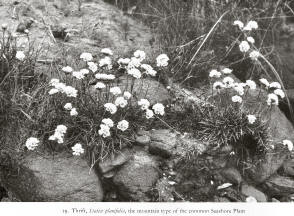

Thrift (Statice maritime) Thrift (Statice maritime)

This is a

very lovely sea-shore plant that is quite common in the mountains. The

mountain plant differs slightly from the seaside form and our British

species is Statice planifolia.

The

Thrift, like many other inhabitants of the mountain slopes, forms dense,

cushion-like tufts of leaves which are often of a considerable

circumferences. The leaves are all very narrow with a single prominent

midrib, and are rather thick in texture, with a smooth glaucous surface.

From the tufts of leaves rise numerous naked flower stalks which are three

or more inches in height and crowned by a conspicuous globular head of

pink flowers.

The head

is surrounded by an involucre of transparent, chaffy bracts which protect

the flowers whilst in bud. Each head is composed of many little florets,

each one of which is produced on a short pedicel which springs from a

chaffy bract.

Each

floret consists of a tiny calyx which is tubular and crowned by five

pointed teeth. The five rose-pink petals are included in the calyx tube

are arranged to form a cup-shaped corolla. At the base of the calyx tube

we shall find the ovary with tiny yellow nectaries at its base. The ovary

is surmounted by five styles. Their bases are covered with white, silky

hairs, which protect the entrance to the tube and nectarines, thus keeping

out insects which have no right there. In a newly-opened flower, we

should find that the styles are pressed back against the petals, the

stamens occupying the centre of the bloom. When this flower is visited by

an insect it is dusted with pollen from the anthers. If we looked at an

older flower, we should notice that the anthers were withered and that the

styles had moved in to take up the same position as the stamens originally

held. Thus, an insect arriving from a newly-opened flower will leave some

pollen on the style and cross-pollination is assured.

Many

insects such as flies, hover-flies, etc., visit the showy blooms for

pollen, but only bees and butterflies can read the nectaries.

Pollen-seeking insect do not pollinate the flowers, as they only visit the

newly-opened blooms where the anthers contain pollen. They do not visit

older flowers with receptive stigmas, as in these flowers no pollen is

left in the anthers. The nectar-seeking insect, on the other hand, will

visit both newly-opened and older blooms, thus ensuring pollination. They

are the chief benefactors.

Alpine Scurvy-grass (Cochlearia alpina) Alpine Scurvy-grass (Cochlearia alpina)

This

plant is very similar to the Common Scurvy-grass so abundant on

sea-shores. It possesses thick, water-conserving leaves, and produces a

raceme of small white flowers which are visited by flies and small bees.

Sea-Campion (Silene maritime)

This

plant belongs to the same family as the Moss Campion. Its short creeping

stems often cover quite large areas, and thus we have another plant which

forms large colonies to the exclusion of others. The stems are covered

with small, fleshy leaves which have a waxy coat which gives them a

grayish appearance. They contain water-conserving tissue. The waxy layer

prevents any water being lost through the upper surface.

The

colonies give rise to many flowers which are produced on short stalks,

only one flower occurring at the summit of each stem. The flower is large

with the same structure as that of the Moss Campion. It is white with a

black spot at the base of each petal limb. The calyx is swollen and

becomes much inflated around the maturing capsule. It is visited by bees,

butterflies and moths.

Seaside Plantain (Plantago maritime)

This

plant possesses a rosette of long, narrow, fleshy leaves and a

deep-striking tap-root. Its flowers are produced on a tall, stout stem

and are arranged in a long spike. They are greenish in colour with a

membranous perianth. They do not produce nectar, being wind fertilized.

The stamens and the pistils occur in the same flower, but as the stigmas

appear before the stamens, self-fertilization is avoided.

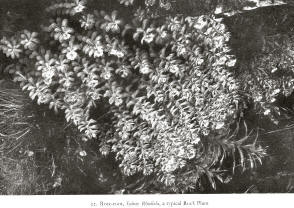

Roseroot (Sedum Rhodiola) Roseroot (Sedum Rhodiola)

This is a

very common plant in rocky places and on the faces of precipices. It

belongs to the same family as the Houseleeks and Stonecrops, which are

themselves typical rock plants.

It

possesses a large, thick, underground stem which grows in crevices of the

rocks and is usually so well fixed in its home that it is impossible to

dig the whole plant out. This stem is a storehouse for food reserves

which are collected in its tissues during the summer in readiness for the

next season. From the rhizome arises a very leafy stem which is crowned by

a mass of bright yellow flowers. The leaves are very thick and succulent

and consist largely of tissues in which water can be conserved. In dry

periods, when the roots can obtain little water in their poor rocky soil,

the plan can draw on its water reserves and thus thrive.

The

bright yellow flowers are very attractive and, as the secrete nectar, are

visited by many insects, especially bees, butterflies and hover-flies.

|