|

To know the wind and weather will make the salmon

spring; To know the spot of heather that hides the strongest wing; To

tell the moon's compliance with hail, rain, wind and snow; Hat ha! this

is the science of Roger Goodfellow.—Noctes

Ambrosanae.

THE close association of grouse with the Heather

will afford, it is hoped, ample apology for the introduction of the

present chapter.

The existence of grouse among the Heather, and the

service rendered by the plant to the birds, attracted the attention of

the early historians of Scotland. Bellenden, in his translation of Boece,

writes: "In Scotland ar mony mure cokis and hennis quhilk etis nocht bot

seid, or croppis of hadder."

This statement is reflected in the following:

Within the fabric rude

Or e'er the moon waxes to the full,

The assiduous dame the spotted spheroid sees

And feels beneath her heart, fluttering with joy.

Not long she sits,

till with redoubled joy

Around her she beholds an active brood

Run to and fro, or through her covering wings

Their downy heads look out: and much she loves

To pluck the Heather

crop, not for herself,

But for their little bills. Thus, by degrees,

She teaches them to

find food which God

Has spread for them in desert wild.

And seeming barrenness.

Grouse were usually taken by hawking and netting

until shooting flying was introduced, which is said by Fosbroke to have

been in 1725.

Grouse, says St. John, generally make their nest

in pL high tuft of Heather. "The eggs are peculiarly beautiful and

gamelike, of a rich brown color, spotted closely with black. Although in

some peculiarly early seasons the young birds are full grown by the 12th

of August, in general five birds out of six which are killed on that day

are only half come to their strength and beauty. The 20th of the month

would be a much better day on which to commence their legal persecution.

In October there is not a more beautiful bird in our island; and in

January, a cock grouse is one of the most superb fellows in the world,

as he struts about fearlessly with his mate, his bright red comb erected

above his eyes, and his rich dark brown plumage shining in the sun.

Unluckily they are more easily killed at this time of the year than at

any other; and I have been assured that a ready market is found for

them, not only in January, but to the end of February, though in fine

seasons they begin to nest very early in March. Hardy must the grouse

be, and prolific beyond calculation, to supply the numbers that are

killed legally and illegally."

Another writer gives the following description of

the black grouse: "Although a forest-haunting bird, frequenting pine

woods and the shrubby glens of mountain ranges, the black grouse does

not confine itself to such locations, but visits the sides of the

heath-clad hills, or the wide, open moorland, where the bilberry plant

abounds, and also makes incursions into cultivated tracts for the

purpose of feeding upon the grain of oats, or rye, or often upon the

blades of corn.

"During autumn and winter the males, having laid

aside their mutual animosity, associate together in small flocks, apart

from the females; but in the spring they separate, and each chooses and

maintains his own exclusive territory. Here he calls the females around

him, but these soon wander away in search of sites for incubation,

where, unassisted, they rear their brood. The eggs vary from six to ten

in number. The young males are clothed in the garb of the females till

the autumnal months, when they acquire the glossy black plumage of their

own sex, with whom they associate till the ensuing spring.

"During the winter, when the snow is deep, the

black grouse feeds upon the tops and buds of the birch and alder, and

also upon the young and tender shoots of the fir and pine, as well as of

the tall heath.

"The red grouse, according to ornithologists, is

confined exclusively to the British Isles. As a rule, it may be said

that wherever in extensive hilly moorlands the Ling or Heather prevails,

there, unless driven from its asylums, the red grouse will be found in

more or less abundance.

"They pair in January and breed in March. The

nest, if we may so call it, is composed of twigs of Heather, wiry

moorland grass, often cotton grass intermixed with a few feathers or a

little coarse sheep's wool. Sometimes the nest is placed under a deep

covert of Heather; but we have seen it amid bilberry bushes; in patches

of cotton grass; and, occasionally, in depressions surrounded by low

herbage, such as wild thyme, etc., midway on the mountain side."

The industry of the birds, if it can be so termed,

is thus quaintly pictured by Wm. Black in "White Heather":

Ronald Strang, in conversation with Carry Hodson,

remarks:

"There are six—seven—blackcocks; do ye see them ?"

"Oh.. yes. What handsome birds they are!" she

said, with a curious sense of relief.

"Ay," said he, "the lads are very friendly amongst

themselves just now; but soon there will be wars and rumors of wars when

they begin to set up house each for himself. There will be many a

pitched battle on those knolls there. Handsome? Ay, they're handsome

enough; but handsome is as handsome does. The blackcock is not nearly as

good a fellow as the grouse-cock, that stays with his family and

protects 'them, and gives them the first warning if there's danger.

These rascals there wander off by themselves and leave their wives and

children to get on as they can. They're handsome, but they're ne'er-do-weeIs.

There's one thing: the villain has a price put on his head; for a man

would rather bring down one old cock thumping on the grass than fill his

bag with gray hens."

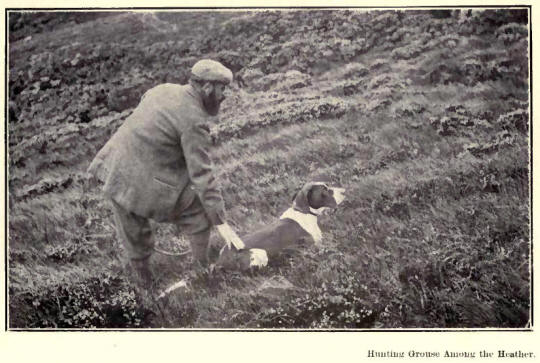

Grouse shooting in Scotland and other parts of

Great Britain has long been classed among the most enjoyable of sports.

It commences on August 12, ending on the 10th of December, and so great

is its hold on British lawgivers that it has been facetiously remarked

that "the grouse season rules the Parliamentary recess," although

Professor Blackie, with equal facetiousness, has told us: "A London

brewer shoots the grouse. A lordling stalks the deer." And, as the poet

sings:

Who treads on the heather will ne'er feel the

gout,

Though to health he has been a wild sinner;

Nor die of a

surfeit, though after a bout

With some chief at a true Highland

dinner.

It has been recorded that the total sporting

capital of Scotland is estimated at about Ł12,000,000 sterling. The

sporting rental of the shire of Inverness alone is estimated at L5o,000

a year, in calculating the rental of a moor, and this allows a guinea

for every brace of grouse shot on it. Or, as another writer puts it:

"'The Heather is cheap enough,' we are sometimes told; 'it ranges from

about seven pence to eighteen pence an acre;' but the extras amount up

to a tidy sum before the season closes. * * * No good shooting with a

comfortable residence upon it can be obtained much under two hundred and

fifty pounds for the season; but the expenses concomitant largely

augment that sum."

The Rev. Hugh Macmillan thus pictures the

associations of the sport: "The fresh, exhilarating air of the hills,

laden with the all-pervading perfume of the heather bells; the

magnificent prospect of hill and valley stretching around; the blue

serenity of the autumnal sky; the carpet of flowering Heather glowing

for miles on every side, and so elastic to the tread: the vastness and

profundity of the solitude; as well as the strange and unfamiliar sights

and sounds of the scene—all these appeal to that poetical spiritual

faculty which is latent even in the most prosaic statistician of St.

Stephen's."

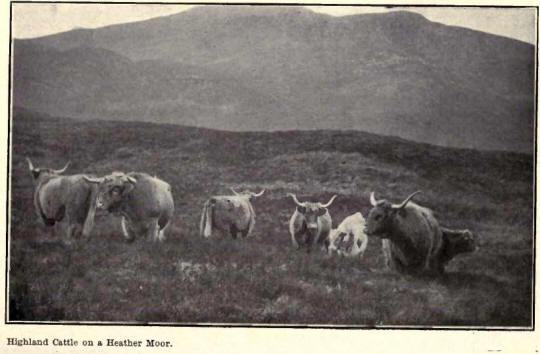

The diseases of the grouse and their causes have

long given concern to the ardent sportsman; and the matter has been

frequently discussed. About half a century ago several contributions on

the subject appeared in "Chambers' Journal." One writer remarked: "It

would seem from a series of articles that sheep are in excess, which is

very naturally the case now in Scotland on many moors. The Heather must

be burned to a great extent to make room for them and to produce fresh

food, which is depriving grouse of shelter. In the next place, as sheep

are perpetually in motion, they constantly disturb the ground, and in

the breeding season unquestionably destroy the nests, and in the autumn

they are dressed with an ointment composed of butter, tar and mercury.

The question then arises as to whether the dressing so far affects the

constitution of the sheep for a time that the soil and herbage are

influenced thereby so as to be prejudicial to grouse."

Another writer, in the same journal, says: "Let

Scotland return to its natural state, as I found it in 1832, and feed on

its grouse portions the Highland black-faced sheep in place of its

foreign usurper, the white-faced Cheviot. The black-faced requires less

care, less burning of the Heather, less gathering and driving, less

grease and tar, stains the ground less. travels less in bodies, and with

its quick eye and light, careful tread, respects the nest and eggs of

its native companion."

Colonel Whyte, an authority, remarks: "The place

the grouse loves to feed on is knolly ground, with the young, short

Heather sprouting up; and this is precisely the spot which the sheep

selects for his nightly resting place. Can we wonder, then, at the

livers of grouse being diseased, feeding, as the birds do, on Heather

besmeared with mercury?"

"The diseases of the grouse," says an authority,

"a contagious epidemic like cholera, scarlet fever or measles; bad

Heather; the consequences of overstocking unwholesome food; atmospheric

influences; tape worms dropped from sheep in embryo form and taken up by

the grouse in their food; and liver complaint. Disease proceeded from

lead poisoning, caused by the grouse eating shot. Shot, by oxidation,

becomes the color of whortleberries; it is thought that the grouse

picked them up in mistake for these berries.

"The most wholesome food for the grouse are the

young and tender shoots of the Heather. Old, rank Heather, and decayed

fibers, lack the conditions requisite for a healthy condition of grouse,

and are not duly assimilated in the system of the bird; disease of the

liver, from the results of which they speedily die. When there is not a

sufficiency of young Heather for the grouse to feed upon they will take

other food which does not agree with them. Scottish Heather, again, is

of great importance for the nests of the grouse. Grouse never hatch in

long Heather if they can avoid it; nor do they lie in it. Nests are

rarely found in Heather of more than a foot in length. When amid close,

rank heath, the young birds eat the decayed fibers and die of

indigestion. They are also liable to disease from the damp, unhealthy

position when they leave the nests."

Those who have eaten this feathered product of the

Scottish mountains and moors will readily indorse Voltaire's following

characterization: "L'oiseau du Phase et le coq de brujčre de vingt

ragôuts I' appret delicieau charment Ic nez, le palais, et les yeuz."

The following description of "How to Eat Grouse"

is by the famous French chef, M. Soyer: "There is a wonderful gout in

your bird of the Heather which baffles me; it is so subtle that I fail

to analyze it. It is, of course, there, because of the food that it

eats, the tender, young shoots of your beautiful heath; but it is

curious, sir, that in some years these birds are better than in others.

Once in about six seasons your grouse is surpassingly charming to the

palate; the bitter of the backbone is heavenly, and the meat on the

fleshy part of short and of exquisite flavor; but for common I feel no

difference. In all other years the best is mediocre, and not any

attentions of my art will improve it. In such years I leave it alone;

but in the years of its perfection I do eat one bird daily, roasted, and

with nothing—no bread sauce, no crumbs, no chips—no, nothing, except a

crust of bread to occasionally change my palate. Ah, sir, grouse, to be

well enjoyed, should be eaten in secret; and take my experience as your

guide: Don't let the bird you eat be raw and bloody, but well roasted;

and drink with it, at intervals, a little sweet champagne. Never mind

your knife and fork; suck the bones, and dwell upon them. Take plenty of

time. That is the true way to enjoy a game bird."

The love of the Professor, as portrayed in Notes,

for the royal sport is well known, a love not wholly shared in by the

more poetic and sensitive Shepherd, who thus addressed some unfortunate

victims of the Professor's skill with the rifle: "The bonny gray hens. I

could kneel down on the floor and kiss ye, and gather ye up in my airms

and press ye to my heart till the feel o' your feathers filled my veins

wi' love and pity, and I grat to think that never rnair would the hill

fairies welcome the gleam o' your plumage risin' up in the morning licht

amang the green plots on the sloping sward that, dipping down into the

valley, retains here and there, as though loth to lose them, a few small

stray sprinklings of the Heather bells."

The Gaelic term for the male bird is

Coileachfraoch, i. e., heather cock; and for the female Cearcfraoch, i.

e., heather hen.

The cry of the grouse sounds like the words, "go,

go, go, go back, go-o back!" But Mr. McGillwray (British Birds, I., p.

181) says "that the Celts, naturally imagining the moor-cock to speak

Gaelic, interpret it as signifying, "co, co, co, co, mo-chlaidh, mo-chlaidh

1" i. e., "Who, who, who, who (goes there?), my sword, my sword!"

Mr. Campbell, in his "West Highland Tales" (I., p.

227), explains it thus: "This is what the hen says: 'Faic thus—a'm la

ud's'n la ud eile.' And the cock, with his deeper voice, replies: 'Faic

thus— an cnoc ud s'n cnoc ud eile.' 'See thou yonder day, and yon other

day,' 'See thou yonder hill, and yon other hill.'

The grouse

occasionally furnished inspiration for Burns, as in the following:

Now westlin' winds and slaughtering guns

Bring

autumn's pleasant weather;

The moorcock springs, on whirring wings

Among the blooming heather.

Again, in that feeling composition where he calls

on his feathered friends to mourn the demise of Captain Matthew

Henderson, "a gentleman who held the patent for his honors immediately

from Almighty God,"

Mourn, ye wee songsters o' the wood;

Ye grouse

that crap the heather bud,

Ye curlews calling thro' the dud;

Ye

whistling plover;

And mourn ye whirring paitrick brood;

He's gane

forever.

|