|

I can heedless look on the siller sea,

I may

tentless muse on the flow'ry lea;

But my heart wi' a nameless rapture thrills,

When I gaze on the cliffs o' my heather hills.

—John Ballantine.

"The grass on the rock, the flower of the heath,

the thistle with its beard are the chief adornments of his

landscape."Ossian.

THE romantic scenery of the Scottish mountains,

their rugged wildness, their indescribable loveliness and charm when

clothed with all the autumnal embellishment of their blossoming purple

Heather, although existing throughout the ages, have only been known to

travelers a little over a century and a half. It is generally believed

that the beauties of the Highland scenery were first brought prominently

before the world by the publication in the year 176o of what the author,

MacPherson, entitled "Fragments of Ancient Poetry Collected in the

Highlands." Geikie tells us that previous to the Jacobite rising the

mountainous region was regarded as the bed of a half savage race into

whose wilds few lowlanders would venture without the most urgent

reasons.

The poet Gray, during his visit to Scotland in the

year 1765. made a brief excursion into the Perthshire Highlands, and

except for the discomforts of travel at that time, came away with a

vivid impression of the grandeur and beauty of the scenery. Writing to

Mason, he says: "The lowlands are worth seeing once, but the mountains

are ecstatic and ought to be visited in pilgrimage once a year. None but

those monstrous creatures of God know how to join so much beauty with so

much horror."

Burns seems to have felt keenly the necessity of

bringing into greater prominence the majesty and loveliness of his

native Scotland. He thus writes to William Simpson, at Ochiltree:

We'll sing auld Coila's plains and fells,

Her

moors red-brown wi' heather bells,

Her banks and braes, her dens and

dells

Where glorious Wallace

Aft bure the gree, as story tells,

Frae Southern billies.

Yet these fair mountains failed to appeal to or

arouse the admiration of some writers and travelers who have viewed

them.

To Dr. Johnson, for instance, they possessed but

little charm. "Of the hills," he says, "many may be called with Homer's

Ida abundant in springs; but few can describe the epithet which he

bestows upon Pelion, by waving their leaves. They exhibit very little

variety, being almost wholly covered with dark heath, 2nd even that

seems to be checked in its growth. What is not heath is nakedness a

little diversified by now and then a stream rushing down a steep. it

will readily occur that this uniformity of barrenness can afford little

amusement to the traveler, that it is easy to stay at home and conceive

rocks and heaths and waterfalls, and that these journeys are useless

labors which neither impregnate the imagination nor enlarge the

understanding." Every Scot can read with amusement the doctor's

characterization of what is conceded the country's greatest charm, when

he remembers that for all things Scottish the gnat lexicographer had an

utter contempt, unless it may have been Scotch broth.

Burt, in his 'tettes-s from a Gentleman in the

North of Scotland," says: "There is not much variety but gloomy spaces,

different rocks, heath and high and low— ' the wild and the dismal

gloomy brown drawing upon the dirty purple, and most of all disagreeable

when the Heather is in bloom,"

Contrast the foregoing with sonic of Sir Walter

Scott's unrivaled pen portraits of the majestic grandeur of Scottish

scenery! Where the fire of the poetic genius is wanting, or where exists

the lack of enthusiastic appreciation of Nature's most sublime

handiwork, one can well conceive of a production so dull and urn

interesting as Burt affords.

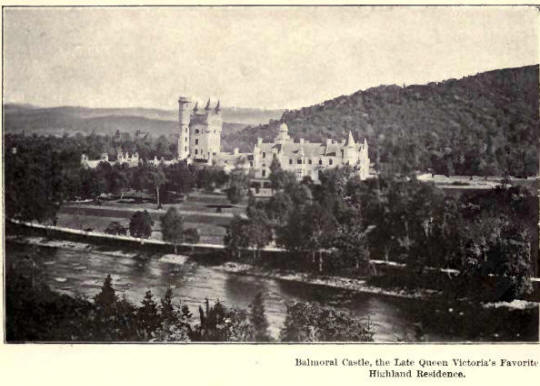

To her late Most Gracious Majesty Queen Victoria

the mountains of Scotland, and their infinite charm, were a never-ending

source of delight. Her Majesty's unique works, "Leaves From Our Journey

in the Highlands" and "More Leaves," abound in passages portraying the

impression made by the Scottish scenery upon the late Queen. Writing of

the trip through the Clachan of Aberfoyle, she says: "Here the splendid

scenery begins—high, rugged and green hills (reminding me again of

Pilatus)—very fine large trees and beautiful pink Heather, interspersed

with bracken, rocks and underwood, in the most lovely profusion, and Ben

Lomond towering up before us with its noble range." Again: "Altogether

the whole drive along Loch Aid, and then by the very small Loch Dow and

the fine Loch (Ion, which is very long and lovely, the Heather was in

full bloom, and of the richest kind, sane almost of a crimson color and

growing in rich tufts along the road."

And perhaps one of the grandest tributes ever paid

to Scotland and her people has been penned by Queen Victoria in the

following words which occur in her description of Loch Lomond and its

enchanting environments: "This solitude, the romance and wild loveliness

of everything here, the absence of hotels and beggars, independent

simple people who all speak Gaelic here, all make beloved Scotland the

proudest, finest country in the world. Then there is that beautiful

Heather which you do not see elsewhere. I prefer it greatly to

Switzerland, magnificent and glorious as the scenery of that country

is."

Even when in the late autumn the beauty of the

Highland landscape had begun to pass away, it stilt possessed delight

for the Queen, who lovingly quotes the words of Arthur Hugh Cough, as

expressive of her own feelings:

The gorgeous bright October,

Then when brackens

are changed

And heather blooms are faded,

And amid russet of

heather and fern.

Green trees are bonnie.

Among the many tributes of tender sentiment

cherished by the laze Queen Victoria, stored any in her private album,

was a spray of Heather, "which," says Helene Vacaresco, the Roumanian

poetess and Maid of Honor to the Queen of Roumania, "was taken from the

wedding bouquet presented by Prince Albert to his wife,"

Other writers have beautifully sung the praises of

Scotland's mountain grandeur. A most charming description of a Highland

landscape appears in "Corn-hill,':

"But a Highland landscape is of itself

sufficiently beautiful. It merely requires Heather to give it the

predominant tone and to interest the beholder by means of many

associations sure to suggest themselves when he sees the purple bran.

Take, for instance, the valley of Carry in mid-July. It possesses a

charm of its own, and yet Scotland owns a thousand more valleys which to

a casual observer appear very similar when they are flooded with Heather

bloom, such is the magic of this humble shrub. The prevailing colors in

the open country on either side of the Garry arc reds and purples,

derived mainly from Heather, largely reinforced by clover and vetches.

'These tints are set off by the flaunting blossoms of the broom on every

neglected corner, while the tender waxen Erica tetralix gathers round

the head of each mimic burn that cleaves the moorland. Every here and

there are batches of turnips, while above them on the crags and below

toward the waste spots an ocean of Heather surges in like a flood tide

swallowing up as it were one by one the numberless great black trap

boulders which are piled up in confusion, the gravestones of a long

buried world, and among which tower foxgloves of great size and beauty.

Above tower many huge spruce firs like giants with drooping robes of

green that love to sweep the earth. Some of them have lost their lead,

but another soon takes its place and the disfigurement is speedily

unnoticed in the clouds of foliage high up, its light green tips all

drenched in sunshine. Behind them the mountains break away into the

skies, their shoulders covered with spires of young larch, while

graceful birches come down the foreground intermixed with the heavy

hanging sprays of beech like mountain nymphs which have left their stem

seclusion to draw near to man. In the valley the bracken catches the

sun's rays and midst its glitter the Garry may be discerned of the color

of straw with boulders shining through its stream, like masses of

cairngorm when seen in the shade. Rain has fallen amongst the mountains

during the night, and now the trees shake their leaves over the stream

as it roars underneath, and the foxgloves near it dance in the echoes,

and a thousand little burns running into it trickle everywhere, through

the lichen-spotted boulders. What more typical picture could be selected

for a wild prospect of Highland Heather?"

The Rev. Hugh Macmillan affords us another

picture: "How gorgeous is that miracle of blossoming when summer, with

her blazing torch has kindled the dull brown Heather, and every twig and

spray burst into blushing beauty, and spread wave after wave of rosy

bloom over the moors, until the very heavens themselves catch the

reflection and bend enamoured over it with double loveliness."

Mr. Macmillan also furnishes this delightful

description of a sunset on Ben Lawers: "Never shall I forget that

sublime spectacle; it brims with beauty even now in my soul. Between me

and the west that glowed with unutterable radiance, rose a perfect chaos

of wild, dark mountains, touched here and there with reluctant splendour

by the slanting sunbeams. The glowing defiles were filled with a golden

haze, revealing in flashing gleams of light the lonely lakes and streams

hidden in their bosom; while far over to the north a fierce cataract

that rushed down a rocky hillside into a sequestered glen, frozen by the

distance into the gentlest of all gentle things, reflected from its

snowy waters a perfect tumult of glory. I watched in awestruck silence

the going down of the sun, amid all this pomp, behind the most distant

peaks—saw the fiery clouds that floated over the spot where he

disappeared fade into the cola dead color of autumn leaves, and finally

vanish into the mist of even—saw the purple mountains darkening into the

Alpine twilight, and twilight glens and streams tremulously glimmering

far below, clothed with the strangest lights and shadows by the newly

risen summer moon."

In "Gray Days and Gold" we find that charming

writer, William Winter, the impressionable and discerning poet-critic of

the American theater, thus characteristically voicing his awe of these

Scottish mountains: "Brown with bracken and purple with Heather,* * *

still with a stillness that is awful in its pitiless sense of inhumanity

and utter isolation. It would be presumption to undertake to describe

the solemn austerity, the lofty and lonely magnificence, the bleak,

weird, haunted isolation, and the fairy-like fantasy of this poetic

realm. * * * The mountain road, on its upward course, winds through

treeless pastureland, and in every direction, as your vision ranges, you

behold other mountains equally bleak save for the bracken and the

Heather, among which the sheep wander and the grouse nestle in

concealment, or whirr away on frightened wings."

And again, in "Brown Heath and Blue Bells:" "The

Heather was pink on the sides of the hills and over their grim tops the

white mist was drifting, and in the tender light of morning the

Highlands looked their loveliest when I bade them farewell"

Scotland's loyal sons have sung their country's

superiority over all other lands, and have especially emphasized her

superlative scenic characteristics, through the medium of their

much-loved mountain flower.

Among these pretty boastful eulogies to be found

scattered throughout the songs of Scotland, the few following may claim

unique interest:

Bonnie Auld Scotland

How grand are the mountains of bonnie auld Scotland,

Her torrents'

wild waters, sun-jewel'd and gloaming;

How rosy the breath of each

moorland and heath,

How lovely her lakes, and her valleys how

blooming.

No foreign strand, no classic land,

Earth's fairest

scenes together,

Can win our praise like yonder braes,

And

fragrant hills of purple Heather.

—G. Bennett.

Our Ain Land

They boast o' lands wi' fairer skies,

And fields o' brighter bloom;

But leeze me on our heather-land,

Wi' a' its hamely gloom—

And, tent me weel, there's mony a blink

Its darksome moods atween;

Sweet sunny blinks, that paint our hills

Wi' tints o' gowd and green.

Hurrah, and hurrah,

And hurrah, my merry men!

I wadna gi'e our ain land

For a' the lands I ken.

—William Ferguson.

The Land o' Cakes

Fair flower the gowans in our glens,

The heather on our mountains;

The blue-bells deck our wizard dens,

An' kiss our sparkling fountains.

On knock an' knowe, the whin an' broom,

An' on the braes the breckan;

Not even Eden's

flowers in bloom

Could

sweeter blossoms reckon.

—John Imlah.

The Freedom of the Hills

Oh! what is Scotland's greatest pride?

Is it her streams and fountains,

Lochs, isles, and dark woods spreading wide?

Nay! 'tis her glorious mountains!

Where granite grey and shingly sheen

Fling back the sun together

'Mong yellow whins and brackens green, Or fragrant

purple heather.

—Robert

Bird.

Knowst Thou the Land?

(In imitation of Goethe.)

Know'st thou the land of the hardy green thistle,

Where oft o'er the mountain the shepherd's shrill whistle

Is heard in the gloamin' so sweetly to sound,

Where the red blooming heather and hair-bell

abound?

Hurrah for the Highlands

I have trod merry England and dwelt on its charms;

I have wandered through Erin, the gem of the sea;

But the Highlands alone the true Scottish heart

warms,

Her heather is

blooming, her eagles are free.

—Andrew Park.

That such wild grandeur should have an influence

upon those whom it constantly surrounds is a natural sequence. This

pervading influence is delightfully impressed by Ruskin in the following

passage from "Two Paths:"

"You will find upon reflection that all the

highest points of the Scottish character are connected with impressions

derived straight from the natural scenery of their country. No nation

has ever before shown, in the general tone of its language—in the

general current of its literature—so constant a habit of hallowing its

passions and confirming its principles by direct association with the

charm or power of nature. The writings of Scott and Burns—and yet more,

of far greater poets than Bums, who gave Scotland her traditional

ballads—furnish you in almost every stanza—almost in every line—with

examples of this association of natural scenery with the passions; but

an instance of its farther connection with moral principle struck me

forcibly just at the time when I was most lamenting the absence of art

among the people. In one of the loveliest districts of Scotland, where

the peat cottages are darkest, just at the western foot of that great

mass of the Grampians which encircles the sources of the Spey and the

Dee, the main road which traverses the chain winds round the foot of a

broken rock called Crag or Craig Ellachie. There is nothing remarkable

in either its height or form; it is darkened with a few scattered pines

and touched along its summit with a flush of Heather; but it constitutes

a kind of headland, or leading promontory, in the group of hills to

which it belongs a sort of initial letter of the mountains, and there

stands in the minds of the inhabitants of the district the clan Grant,

for a type of their country and of the influence of that country upon

themselves. Their sense of this is beautifully indicated in the war cry

of the clan, 'Stand fast, Craig Ellachie.' You may think long over those

few words without exhausting the deep wells of feeling and thought

contained in them—the love of the native land; the assurance of their

faithfulness to it; the subdued and gentle assertion of indomitable

courage—I may need to be told to stand, but if I do, Craig Ellachie

does. You could not but have felt, had you passed beneath it at the time

when so many of England's dearest children were being defended by the

strength of heart of men born at its foot, how often among the delicate

Indian palaces, whose marble was palled with horror, and whose vermilion

was darkened with blood, the remembrance of its rough gray rocks and

purple heaths must have risen before the sight of the Highland soldier;

how often the hailing of the shot and the shriek of battle would pass

away from his hearing, and leave only the whisper of the old pine

branches—.'Stand fast, Craig Ellachie.'"

|