|

LIKE the proverbial Scot, the Heather, as has been

seen, is found "far frae its native hame," or what is generally

considered as such, and in some out of the way corners of the globe.

Heather has been discovered in different localities in the United

States, but in most instances it is thought to be adventive rather than

indigenous. For its appearance here the Scotsman is in great measure

responsible. The latest botanical work in America (Britton and Brown's

"Illustrated Flora") thus describes it: "Calluna vulgaris, sandy or

rocky soil: Newfoundland to New Jersey. Naturalized or adventive from

Europe."

Meehan tells us

that when the poet Percival first referred to the Heather as a native of

Vermont, in his "Ode to a Dried-up Lake," his inclusion of the heath

among the flowers that suffered was criticised by botanists, and

considered allowable only under "the poet's license," though still with

the reservation that Shakespeare would not have blundered so:

There the dark fern flings on the night wind's

wings

Its leaves like the dancing feather,

And the whip-poor-will's note seemed gently to

float

From the deep

purple brown of the heather.

But the desire to feel that America, as well as

the land of Burns, had a vested right to the famous plant, was very

strong, and there sprang up an unusual interest in the subject.

Whittier's pretty lines were felt to be real both in body as well as

spirit:

No more these

simple flowers belong

To

Scottish name and lover,

Sown in the common soil of song,

They bloom the wide world over.

In smiles and tears, in sun and showers,

The minstrel and the Heather,

The deathless singer, and the flowers

He sang

of—live forever.

Wild

heather bells and Robert Burns!

The moorland flower and peasant!

How, at their

mention, memory turns

Her pages old and pleasant.

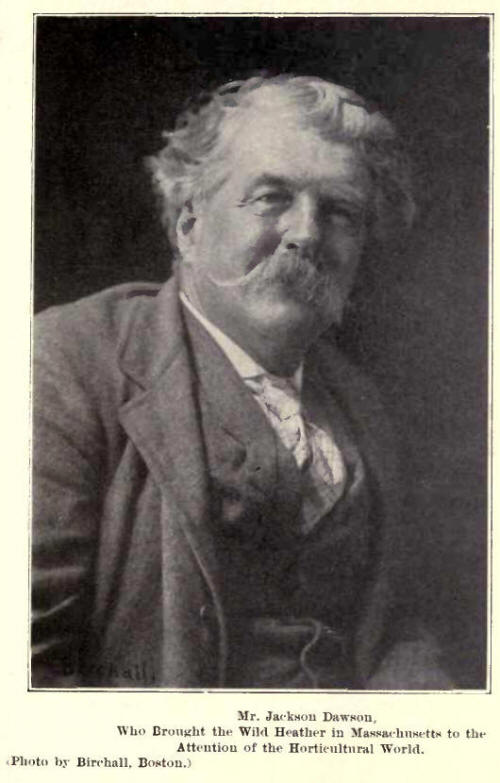

Quite a stir was created in the botanical world

when a plant of Calluna vulgaris, in a pot, was exhibited by Mr. Jackson

Dawson, then a young gardener for Hovey, of Cambridge, Mass., and now

superintendent of the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University, at a show

of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society in Boston, on Saturday, July

13, I86I. Mr. Dawson had discovered the Heather growing wild near

Tewksbury, Mass. So great was the enthusiasm in the matter that the

Society at once instituted an investigation, and on August 5 of the same

year its Flower Committee were dispatched on an errand of discovery. The

Heather was then in full bloom. The chairman of the committee, Mr. E. S.

Rand, reported that plants were found half a mile from the State House

of Tewksbury, and were spread over an extent of perhaps half an acre.

In the locality where the plants were growing the

surface of the ground was buried by small hummocks and covered with a

short close grass, interspersed with numerous plants of Kalmia

angustifoha, Spira tomentosa, Cassandra calyculata, Azalea viscosa and

Myrica Gale. In several cases the Heather was found overgrown and shaded

by these shrubs. The common cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) occurred

somewhat abundantly in the immediate vicinity of the Heather, usually on

the depressions, while the Heather was found on the hummocks. The soil

was sandy peat, just that which the gardeners would choose for heaths.

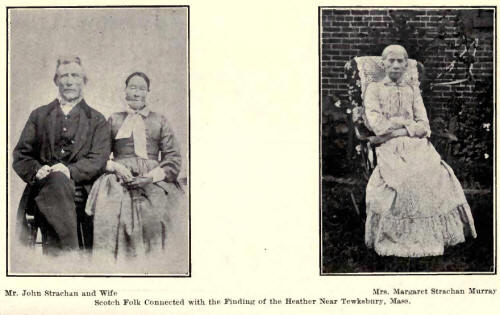

The first supposition was that the Heather had

been planted, or the seed sown by a Scotchman, Mr. Strachan, who lived

near by, but in an interview he denied all knowledge of the plant until

within a few years, said he had never had any Heather in his possession,

had never received any seeds from Scotland, or done anything in any way

by which the plants might have been introduced; that he was as much

astonished as delighted when, about ten years before, he discovered the

plant, which he at once recognized as the Scotch Heather, and each year

since he had gathered it when in blossom to adorn his house. On being

further pressed by one of the committee as to the feasibility of its

being introduced by him, lie indignantly and characteristically replied:

"Wadna I hae been a fule, mon, to sow it on another man's land, when my

ain as guid wad hae grown it as weel?"

The former owner of the land remembered the plants

in i8io, and from deductions the committee believed that the plants

existed about 1700.

In

concluding his report, Chairman Rand remarked: "May not the Heather once

have existed in profusion on this continent, and have gradually died out

owing to some inexplicable, yet perhaps only slight, climatic changes?

May not this be the last vestige, or one of the last, of what was once

an American heath? And if the Heather exists in Nova Scotia and

Newfoundland, may we not expect that some intermediate stations may yet

be discovered?"

An

abridgment of Mr. Rand's report appeared in Silliman's Journal, the

editors of which periodical in a foot note state: "That Calluna also

inhabits Nova Scotia, is stated by Loudon, in his Arboretum, we know not

upon what authority, but should be glad to be informed. If the claim for

Calluna to be regarded as an American plant rests mainly or wholly upon

this Tewksbury locality, it would not gain acceptance; but its existence

in Newfoundland, and still more in Nova Scotia (if verified), does away

with all antecedent improbability of its indigenous occurrence in New

England."

In the same

periodical the discussion of the subject was continued for a

considerable time, and I think it of sufficient interest and value, both

to scientists and laymen, to warrant its insertion in full here. It

follows:

That "America

has no heaths" is a botanical aphorism. It is understood, however, that

an English surveyor, nearly thirty years ago, found Calluna vulgaris in

the interior of Newfoundland. Also that Dc la Pylaie, still earlier,

enumerates it as an inhabitant of that island. But this summer (1861)

Mr. Jackson Dawson, a young gardener, has brought us specimens and

living plants (both flowering stocks and young seedlings) from

Tewksbury, Mass., where the plant occurs abundantly over about half an

acre of rather boggy ground, along with Andromeda calyculata, Azalea

viscosa, Kalmia angustifolia, Gratiola aurea, etc., apparently as much

at home as any of these. The station is about half a mile from the State

Almshouse. Certainly this is as unlikely a plant, and as unlikely a

place for it to have been introduced by man, either designedly or

accidentally, as can well be imagined. From the age of the plants it

must have been there at least a dozen years; indeed, it has been noticed

and recognized two years ago by a Scotch farmer in the vicinity, well

pleased to place his foot once more on his native Heather. So that even

in New England he may say, if he will—as a friend of ours botanically

renders the lines-

"Calluna

vulgaris this night shall be my bed,

And Pteris aquilina the curtain

round my head."

It may

have been introduced, unlikely as it seems, or we may have to rank this

heath with Scolopendrium officinarum, Suhularia aquatica and Marsilea

quadrifolia, as species of the Old World so sparingly represented in the

New that they are known only at single stations—perhaps late lingerers

rather than newcomers.

A

further comment is as follows: The earliest published announcement that

we have been able to find of Calluna vulgaris as an American plant is

that by Sir Wm. Hooker, in the index to his Flora Boreali-Americana (2p.

280), issued in 1840. Here it is stated that: "This should have been

inserted at p. 89, as an inhabitant of Newfoundland, on the authority of

De la Pylaie. Accordingly, in the seventh volume of De Candolle's

Prodromus, to the European habitat is added 'Etiam in Islandia, et in

Terra Nova Americe Borealis.'" But it does not appear that Mr. Bentham

had ever seen an American specimen. He also overlooked the fact (to

which Dr. Seemann has recently called attention) that Gisecke, in

Brewster's Encyclopedia, records it as a native of Greenland. No mention

is made of it by Dr. Lang in his enumeration of the known plants of

Greenland, appended to Rink's Geographical and Statistical account of

Greenland, published in 1857. from which we may infer that the plant is,

perhaps, as rare and local in Greenland as in Newfoundland, or even in

Massachusetts.

In this

journal for September, 1861, the present writer announced the unexpected

discovery by Mr. Jackson Dawson of a patch of heath in Tewksbury, Mass.,

adding the remark that "It may have been introduced, unlikely as it

seems, or we have to rank this heath with Scolopendrium officinarum,

Subularia aquatica, and Marsilea quadrifolia, as species of the Old

World so sparingly represented in the New that they are known only at

single stations—perhaps late lingerers rather than newcomers." And when,

in a subsequent volume of this journal, Mr. Rand, after exploring the

locality, gave a detailed account of the case, and of the probabilities

that the plant may be truly native, we added a note to say that the

probability very much depended upon the confirmation of the Newfoundland

habitat. As to that, we had been verbally informed, in January, 1839, by

the late David Don, that he possessed specimens of Calluna collected in

Newfoundland by an explorer of that island. Our friend, Mr. C. J.

Sprague, however, after having in vain endeavored to find in any

publication of Pylaie's any mention of this heath in Newfoundland, and

having ascertained that no specimen was extant in Pylaie's herbarium or

elsewhere, that he could trace, naturally took a skeptical view, and in

the proceedings of the Boston Natural History Society for February and

for May, 1862, he argued plausibly, from negative evidence, against the

idea that any native heath had ever been found in Newfoundland or on the

American continent. It is with much interest, therefore, that we read

the announcement of Dr. Hewett C. Watson (in the Natural History Review

for April last) that:

"Specimens of Calluna vulgaris from Newfoundland have very recently come

into my hands, under circumstances which seem to warrant its reception

henceforth as a true native of that island. At the late sale of the

Linnan Society's collections in London, in November, 1863, I bought a

parcel of specimens, which was endorsed outside: 'A collection of dried

plants from Newfoundland, collected by McCormack, Esq., and presented to

Mr. David Don.' The specimens were old, and greatly damaged by insects.

Apparently they had been left in the rough, as originally received from

the collector; being in mingled layers between a scanty supply of paper,

and almost all of them unlabeled. Among these specimens were two

flowerless branches of the true Calluna vulgaris, about six inches long,

quite identical with the common heath of our British moors. Fortunately,

a label did accompany these two specimens, which runs thus: 'Head of St.

Mary's Bay—Trepassey Bay, also very abundant—S. E. of Newfoundland,

considerable tracts of it.' The name 'Erica vulgaris' has been added on

the label in a different handwriting. All the other species in the

parcel (or nearly all) have been recorded from Newfoundland, so that

there appeared no cause for doubt respecting the Calluna itself. And,

moreover, the collector had seemingly some idea that a special interest

would attach to the Calluna, since in this instance he gave its special

locality, and also added two other localities on the label. But there is

very likely some mistake in the name of the donor to Mr. Don. It is

believed by Sir William Hooker that he was the same Mr. W. E. Cormack

whose name is frequently cited for Newfoundland plants in the 'Flora

Boreali-Americana.' This gentleman was a merchant in Newfoundland, to

which he made several voyages."

We should recollect that the Calluna advances to

the extreme western limits (or out-hers) of Europe, in Iceland, Ireland

and the Azores. The step thence to Newfoundland and Massachusetts,

though wide, is not an incredible one.

Without doubt these are the very specimens

referred to by Mr. Don, then curator of the Linnan Society. And now that

the stations where they were collected are made known, we may expect

that the plant will soon be rediscovered and its indigenous character

ascertained.

We notice

that an earlier announcement of Dr. Watson's discovery is contained in

Dr. Seemann's Journal of Botany for February last, where the record of

Gisecke's discovery of Calluna in Greenland is referred to. In view of

this, and of its common occurrence in Ireland, Iceland and the Azores,

Dr. Seemann opines that "its extension to Newfoundland and the American

continent is, therefore, not so much a paradox as a fact at which we

might almost have arrived by induction." It seems to us that the

induction was all the other way until the plant was actually discovered

on American soil.

In Vol.

38, P. 428, 1864, of Silliman's Journal, occurs the following:

The Newfoundland habitat of Cahluna having been

confirmed (vide this journal, 38-123). we have now pleasure to announce

that Professor Lawson—late of King's College, Kingston. now of Dalhousie

College, Halifax—has had the good fortune to bring to light a new

locality from the Island of Cape Breton. The flowering specimen which

Professor Lawson sent us was collected on the 30th of August last, "in a

wet, spongy place, among spruce stumps, in a peaty soil, overlying clay,

on the farm of Mr. Robertson, St. Ann's, Inverness Co., Cape Breton

Island." He states that "it has been known there for ten years, having

been noticed by a Highlander when mowing, who immediately ran to his

master, Mr. Robertson, exclaiming, 'I have found Heather.' Full inquiry

into the whole circumstance leads me to the belief that the Calluna has

not been planted at St. Ann's, but is a genuine native. There is only a

small patch of it, not much more than a yard across. Its surroundings at

St. Ann's are most appropriate. Both in scenery and vegetation there is

a striking resemblance to the Scotch Highlands. Gaelic is the common

language, and all the genuine manners and customs of the Highlands are

there."

It is interesting

to note that the Heather appears to be even more restricted in this new

station than that at Tewksbury, Mass., the indigenous character of which

it helps to establish. We may now fairly infer that the Heather once

flourished throughout our Eastern borders, from Massachusetts to

Newfoundland, but it is verging to extinction, not being able to compete

here with the rival claimants of the boggy soil.

Other contributions on the subject appearing in

the journal named are:

Calluna Vulgaris in Newfoundland

Mr. Murray, late of the Geographical Survey of

Canada, and now engaged in a survey of Newfoundland, has brought to

Montreal specimens of this plant, which were collected by Judge Robinson

on the east coast of Newfoundland (near Ferryland, lat. 47, long. 52

56), and which are stated to be from a small patch of the plant not more

than three yards square.

The question whether Calluna is or is not indigenous to the New World,

which during several years past has been repeatedly referred to in this

journal, as additional facts come to our notice, has now taken a new

turn, Dr. Seemann in his Journal of Botany for October last having

published and neatly figured "the Newfoundland Heather as a distinct

species Calluna atlantica." He founds it upon specimens originally from

Newfoundland which have been for some years cultivated by Dr. Moore in

the Glasnevin Gardens, Dublin, side by side with the common European

Heather. The diagnosis attempted Dr. Seemann admits to be as yet far

from satisfactory, except as to a biological distinction observed by Dr.

Moore, viz.: "that whilst the Newfoundland one always suffered from

frost and turned brown during the mild Irish winter, the common British

form growing by its side was unaffected by cold, and retained its usual

green color." Although "no argument can possibly set aside" this fact,

yet its value as a character has to be considered. Probably in the

station from which these specimens were lately transferred, as well as

in Iceland and the higher Alps, whence Dr. Seemann has the same form,

the plant was accustomed to complete protection by snow from changes of

temperature the whole winter through. Unfortunately, we have no

specimens from Newfoundland, and Dr. Seemann does not speak of the Cape

Breton, Nova Scotian, or New England plants. Upon examination of these,

we do not find that the indicated differences in structure (mainly the

naked pedicels, broader sepals, and tip of flowering branches not

continued into a leaf shoot while the flowering lasts) coincide or hold

out. So that as yet a second species can hardly be said to be

established.

There is a

story told that the plant was introduced into the maritime provinces by

some Scottish emigrants who on the voyage thither used the Heather as a

bed, as they were wont to do in their native country; brought the

material on shore; the seeds got scattered and finding an agreeable

soil, took lodgment, rooted and flourished.

Heather is also found introduced at Halifax, but

is said to have been brought over from Scotland by some soldiers of a

Highland regiment once stationed there. It was planted near one of the

forts, and has thriven well. There is now a quarter of an acre of

Heather at Point Pleasant Park, Halifax.

S. S. Bain, a prominent florist of Montreal, and a

Scotsman, writes me that two friends of his, also from Scotland,

prospecting for the yellow metal on the Yukon, found themselves on a

mountain overtaken by the darkness. They made their bed as best they

could, and when morning light came they discovered they had been

sleeping on a bed of Heather. The location was above the snow levels,

and the plants were beautifully in flower at the time. A sprig in the

possession of Mr. Bain confirms this little story.

The latest deductions from a scientific standpoint

regarding the indigenous character, or otherwise, of the Heather in the

United States, appears in the March, i9oo, issue of Rhodora, the journal

of the New England Botanical Club, from the pen of Mr. William Penn

Rich, now Secretary of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society at

Boston, Mass. Mr. Rich writes:

"On the twenty-fourth of September, 18, the

writer, happening to be in Tewksbury, Mass., visited the location of the

Heather (Calluna vulgans, Salisb.), and it may be desirable to put on

record the present condition of this interesting plant as well as some

observations on the vexed question of its origin. "Contrary to our usual

experience in such matters, no difficulty was met with in finding the

place where it grew, so well was the plant known in the town.

"It grows upon a hillside pasture sloping

gradually down to boggy ground through which a deep channel has been cut

by a brook. In the higher part of this pasture a few scattered patches

of the plant were noticed, possibly transplanted from the main body of

the Heather, and from their feeble appearance seemingly doomed to early

extinction. The principal growth was in the lower part of the pasture,

on the borders of the brook, where the plants were growing quite thickly

in a space about thirty feet square, which was inclosed by a wire fence.

At the time of our visit a cow was standing in the midst of the precious

shrubs, an invasion not likely to be soon repeated, for visiting the

place a second time, some weeks later, we found the fence had been

repaired, showing the watchful care of some interested person over this

rare plant. The shrubs were mostly in advanced fruit, although a few of

their pretty rose-colored flowers still lingered as a sample of their

beauty a few months before.

"In the thirty-eight years which have elapsed

since public attention was first called to the Heather in this locality,

the area of its growth has been much reduced, judging from the

description published at the time, and that it is still in existence is

doubtless due to the protection which has been afforded it. Since its

discovery here several other stations have been found for the Heather in

New England. It has been reported from Cape Elizabeth, Maine, from West

Andover, Townsend, and Nantucket, Massachusetts, and also from Rhode

Island.

"In most of these

locations careful investigation has failed to prove its introduction by

human agency, and this has led numerous writers on the subject to claim

for it an indigenous origin. Although its early history in New England

is shrouded in obscurity, and desirable as it would be to place the

Heather on our list of native plants, it might be said, after a careful

reading of the literature of the subject, that no satisfactory evidence

has accumulated during the years that have passed since its discovery on

this continent to substantiate its claim as a plant native to America.

"The circumstances that in some instances, as at

Townsend, Mass., it has been traced to the planting of seed, and

especially the fact that although many wild regions in America seem

favorable for its development, it has never been found at points remote

from human habitation, are much against the theory of its indigenous

character.

"The

occurrence of the Heather in Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Greenland,

has been adduced as strong evidence in favor of believing the plant

native in America. But Nova Scotia was settled in part by Scotch, who

would have been particularly likely to introduce the Heather

accidentally, if not purposely; while in Newfoundland—a region of great

stretches of open moorland, and seemingly an ideal habitat for the

Heather—the plant has only been found in a few patches about the

settlements on the southeastern coast, the most thickly populated part

of the island. Finally, the occurrence in Greenland, although reported,

could not be confirmed by Lange, the author of the most complete flora

of that region. It will thus be seen that these northern occurrences add

little to the evidence that the Heather is an indigenous American

plant."

This is also the

view held by Dr. Goodale, of Harvard University, who has given

considerable study to the subject.

In the first week of August, 1902, the author

visited the spot near Tewksbury, Mass., where the Heather is growing,

and found the conditions much as described by Mr. Rich. Patches of the

plant were seen scattered among the dense vegetation surrounding them,

and in one or more instances bushes had succumbed from some cause or

other, probably our trying variable spring weather, and seemed to be

"stricken in days." Those remaining were of comparatively low growth,

and among them there was observed a tendency to spread. Through this

cause, and the watchful care of the horticulturist at the State House,

who is fully cognizant of the value of the gem in his charge, the

Heather may be long preserved in this locality; for whether native or

introduced, we are thankful, as Superintendent Dr. John Nichols, of the

State Institution, cordially and appreciatively remarked to the author,

"to have so near us this small but pretty reminder of the Highland hills

of far-away Scotland."

And now I desire to bring to a close this entertaining and much

discussed subject of "Heather in America," with a sketchy narrative of

the facts relative to the discovery of the plant, that led to its

finally being brought to public notice, as they were given me by the

lady whose artless story certainly adds a picturesque, if homely,

dramatic aspect to the lively discussion.

That the existence of the Heather at Tewksbury,

Mass., had been known for over a century is conceded by those who have

given the matter any study. The credit of bringing the plant before the

horticultural world must be ascribed to Mr. Jackson Dawson. But a

romantic incident, which has heretofore remained in obscurity, is that

the finding of the Heather at that time, and the bringing of it to the

attention of Mr. Dawson indirectly, is due to Mrs. Margaret Murray, née

Strachan, or "Stratton, as we girls changed it" (to quote the old lady's

quaint remark), a daughter of the Scotch farmer whose land adjoined that

upon which the plant was discovered growing, as previously mentioned in

this chapter. Mrs. Murray,

a sweet-faced old lady, now verging on the

allotted span, resides at Ballardvale, Mass. Here is her story as she

told it: "My attention was attracted to the Heather by its pretty little

purple bells. I pulled a sprig and brought it to my father, who, being a

Scotch-man (he is a native of Auchinblae, Kincardineshire), said: 'Why,

that looks like Scotch Heather!' But to make sure of the matter he took

it to a Scotch friend of his, Alexander Skene, a gardener, then at

Andover, Mass. A few days later we all went down to the field together,

and as soon as Mr. Skene saw the plant he said: 'Of course, that's the

real Scotch Heather.' I gave a few sprigs to a girl friend of mine, who

Jack Dawson, then a young fellow, was comin' round to see; and when he

noticed the sprigs of Heather on her table he wanted to know where she

got them. She told him, and the first thing we knew the public was makin'

a big time over it, and the committee came down to see it. After that

the man who owned the land, who told father that for twenty years he had

been plowing the Heather up to keep it from spreading over the cow

pasture, thinking he could make something out of it, forbade us girls to

go near that spot. It's now many years since I've seen the Heather. I

wonder if it's as pretty as It was then!"

Under the title of "Heather and Weather," Vanity

Fair, in its issue of February 22, 1862, caricatures the committee of

the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, searching for the Heather, as

shown in the accompanying cartoon illustration, and comments as follows:

"A few days ago, as the sun was busily employed in

gilding a very pretty landscape, the passers along a quiet lane at

Tewksbury, near Boston, were arrested by a novel and curious sight.

Several elderly men, some of them stoutish, others scraggyish, but all

of solid and respectable appearance, were seen scattered over an area of

an acre or so in extent, apparently occupied in the process of grazing,

or pasturing themselves upon the scanty herbage, their postures being of

the fashion known as 'all-fours,' and their heads close to the ground.

It was some time before any person had sufficient presence of mind to

address himself to any of the strangers, as, if not grazing, they might

have been praying, and it is not Boston manners to disturb

decent-looking citizens either from their prayers or their provender. At

last, however, a smart shower of rain came down, upon which the

mysterious grubbers arose precipitately to their feet and toddled off to

a neighboring farmhouse for shelter. Here it transpired, upon inquiry,

that the strangers were certain Wise Men of Boston, forming in the

aggregate what is called the 'Flower Committee' of that city, and that

they had been occupied in investigating the subject of a 'native

heather,' said to have been discovered in the field just deserted by

them. They had secured several fine specimens of the plant, and might

have been now in fine spirits about it had not the farmer, a Scotchman,

informed them that it was not Heather, but good, old-fashioned,

rough-and-ragged Scotch thistle, upon which they feed donkeys in his

country. This, combined with the shower, was rather a damper, and the

sages made their way back to Boston with all speed, wetter if not wiser

men."

|