|

Watson, in his Cybele Britannica, gives three

distinct zones of altitude for the distribution of the Alpine plants.

The Super-Arctic Zone, bounded below by the limit of the common Heather

at an elevation of about 3.000 feet; lower down, the Mid-Arctic Zone,

lying between the Heather line and that of the

cross-leaved heath at about 2,000 feet, characterized by the Heather

without the heath. This comprehends the highest mountains of England,

Wales and Ireland, and all the great ranges of Scotland, and contains by

far the largest proportion of rare and beautiful Alpine plants, being

especially rich in Arctic forms. Lastly, the Infer-Arctic Zone, bounded

above by the Erica and below by the bracken and the limits of

cultivation at about 1,400 feet. This distribution cannot, of course, be

accepted as a fixed one.

Rev. Hugh

Macmillan, than whom the Heather has no sweeter singer, thus writes in

his "Holidays on High Lands:"

"The

vegetation of the moorlands is exceedingly varied and interesting. Its

character is intermediate between Arctic and Germanic type, reminding

one, in the prevalence of evergreen, thick, glossy-leaved plants of the

flora of Italy, which seems, from the evidence of ancient records, to

have undergone a remarkable change in modern times, and now approximates

in its general physiognomy to the flora of dry mountain regions. The

plant which, above all others, is characteristic of the moor is, of

course, the common Heather, or Ling. It is one of the most social of all

plants, covering immense tracts with a uniform dusky robe, and claiming,

like an absolute autocrat, exclusive possession of the soil.

"And yet, though capable of growing in the

bleakest spots, and enduring the utmost extremes of temperature, its

distribution in altitude and latitude is singularly limited. It ascends

only to a certain height on the mountains on which it grows; for,

although it covers the summits of most of the hills in England, many of

the loftiest Highland hills rise high above it, green with grass, or

gray with moss and lichens. The upper line runs from two to three

thousand feet in the counties of Perth, Aberdeen and Inverness, varying

according as it grows on an elevated mountain range or on isolated

peaks. On the west coast of Scotland it is very often found on a level

with the seashore, almost mingling with the dulse and bladder-wrack. In

Norway, strange to say, although the general surface of the country is

composed of high and barren plateaux, it is so scarce and local that one

may travel hundreds of miles without finding a single specimen. It is

replaced in such localities by the bearberry and crowberry, which form

immense continuous patches, and look, at a distance, especially when

withered, in spring or autumn, somewhat like Heather. Although abundant

on the European side of the Ural Mountains, it disappears very suddenly

and decidedly on the eastern declivity of the range; and it is entirely

absent from the whole of northern Asia to the shores of the Pacific. Its

northern limit seems to be in Iceland, its southern in the Azores. In

Europe it covers large tracts of ground in France, Germany and Denmark,

particularly in the lands of Bordeaux and the moors of Bretagne, Angou

and Maine; while in Great Britain it exists in every county, with the

exception of Berks, Bucks, Northampton, Radnor, Montgomery, Flint,

Lincoln, Ayr, Haddington, Linlithgow.

"The range of the heath tribe is eminently

Atlantic, or western. It is found along a line drawn from the north of

Norway along the west coast of Europe and Africa, down to the Cape of

Good Hope, in the vicinity of which the family culminates in point of

luxuriance and growth, beauty of flowers and foliage, and variety of

species, some even attaining the arborescent form. Along this line,

which is comparatively narrow, seldom running far from the coast, about

four hundred distinct kinds, excluding varieties, are scattered, of

which England and Scotland possess only four and Ireland no less than

six.

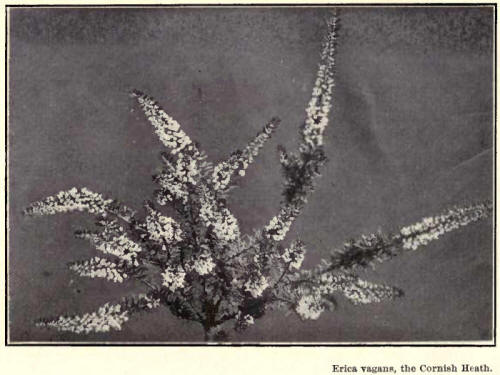

"On the barren moors of Cornwall a very

interesting kind of Heather called the Cornish heath (Erica vagans)

grows abundantly, distinguished by the crowded bell-shaped flowers. On

the north coast of the same county another species occurs, called Erica

ciliaris, with very large and gaily-colored flowers, and leaves

elegantly fringed with hairs. It is frequent near Truro and Penrhyn, and

in one or two places near Dorset. These two Cornish heaths are also

found in Ireland; the one on a little island off the coast of Waterford,

and the other near Clifton, in Galway. In the Emerald Isle, Mackay's

Heather, which has large glabrous foliage, with an unusual proportion of

white under-surface, grows in one or two spots in Connemara. It was

discovered the same year on the Sierra del Feral in Spain. In mountain

bogs in the west of Mayo and Galway the Mediterranean Heather is

sparingly distributed, sometimes obtaining a height of five feet, with

numerous upright rigid branches, and flowers in leafy racemes. The

Scottish Menziesia (M. ccerulea), the most abundant kind of heath in

Norway, is, as I have already said, almost extinct on Dalnaspidal moor

in Perthshire, its only locality in this country (Scotland).

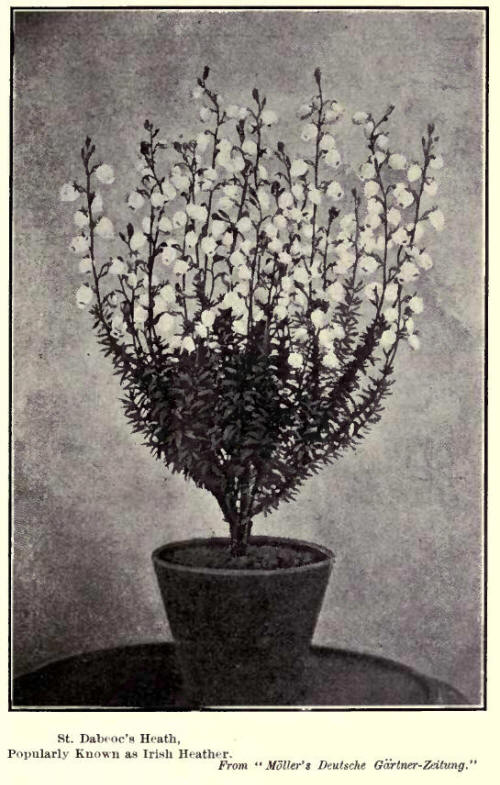

"Every visitor in Ireland must be familiar with

St. Dabeoc's Heath (Menziesia pollifolia), which the guides and peasants

frequently sell to tourists at exorbitant rates as a memorial plant.

This lovely Heather occurs in great profusion on the low granite hills

to the westward of Galway, all the way to the lower end of Loch Corrib.

It grows on heathy moors by the roadsides, and although it is found a

considerable way up the mountain, it is there much less abundant,

smaller in size, and rarely flowers. The common bell heather of our

Highland moorlands (Erica cinerea) produces the finest effect of all our

native heaths, growing as it does in great masses in bare places,

especially where the burning of the common ling has enriched the soil

with its ashes, and removed a formidable competitor in the struggle of

existence. It frequently purples a whole hillside, and nothing finer, as

regards effect of color, can be seen even in the tropics.

"The cross-leaved heath (Erica tetralix) is much

less abundant, growing in boggy places among the yellow spikes of the

aphrodel and the snowy plumes of the cotton grass. It is more like a

hothouse heath, with the rich clustered head of pale rosy blossoms. But

growing sparingly, and its color being more delicate, its effect in the

moss, and at a distance, is not equal to its beauty close at hand.

"That Australia and America have no true heaths is

a botanical aphorism. In Australia the tribe is replaced by the Epacrid,

which are often as beautiful as any of the Cape heaths. In North America

the Scottish Menziesia is more abundant than it is in Scotland, or even

in Norway.

"Hudsonia ericoides, which covers the white sandy

wastes in many parts of New Jersey, is so like the common heath that it

is not infrequently mistaken for it when out of flower.

"It is recorded of the first Highland emigrants to

Canada that they wept because the Heather, a few plants of which they

had brought with them from their native moors, would not grow in their

newly adopted soil. It is understood, however, that an English surveyor,

nearly thirty years ago, found the common Ling in the interior of

Newfoundland; while in one spot in Massachusetts it occurs very

sparingly over about half an acre of boggy ground in the strange company

of andromedas, kalmias and azaleas, peculiar to the country.

"It was first observed by a Scottish farmer

residing in the vicinity, who was no less surprised by its unexpected

appearance than delighted to set his foot once more on his native heath.

None of the plants seems to be older than six years, and may, therefore,

have been introduced by someone who found relief from homesickness in

forming the simple floral link between the new and the old country."

A fuller account of this discovery, and the

discussion upon it which ensued, is given in the chapter entitled "The

Heather Abroad."

In Koerner and Oliver's "Natural History of

Plants" occurs the following passage relative to the distribution,

hardiness and other characteristics of the Heather, which, it will be

observed, is here dealt with under the name of Ling:

"The common Ling may be traced in an unbroken

range from the plains up to a height of 2,450 meters on the slopes of

the Alps. Strange to say, these plants do not blossom much earlier on

the lowlands than on the high Alpine regions, and it has actually been

shown that Calluna blooms rather sooner at a height of 2,000 meters than

in the northern portion of the Baltic lowlands. How is this? The winter

snow has long disappeared from the lowlands, while the hillsides above

are yet concealed under their cold, white covering. The winter snow has

gone, to be sure, but not the winter. While everything around is already

in blossom, while the ear is already visible on the stalks of rye, the

neighboring moor is still a dismal waste, and lifeless a month or so

later; there is a stir on the dry soil of the cold moor, and the

absorbent roots of the plants, which have evergreen rolled leaves,

commence their activity. When the warm days of midsummer arrive, and the

sun sends down its powerful rays, the temperature of the soil quickly

increases, and, indeed, rises far more than would be thought possible. A

thermometer placed three cms. below the surface in the uppermost mossy

layer of a moor, on a cloudless summer day (June 22) showed a

temperature of 31, while the temperature of the air in the shade was 13

degrees. An unpleasant vapor arises from the damp earth, which settles

on the surface, and makes a walk over the moor particularly

disagreeable. Scarcely has the sun set in glowing red on the horizon

when this vapor condenses into 'baths' of mist, which settles over the

dark expanse; stems, branches and leaves are covered with drops of

water, and next morning everything is as thoroughly soaked as if it had

rained all throughout the night. This process, which is regularly

repeated during the fine weather, is only interrupted when a damp wind

from the sea blows, driving masses of clouds over the heath, or when

copious rains saturate the soil. It needs no further showing that under

such conditions an abundant and continuous transpiration from the plants

is impossible, and that in the short intervals which are allowed to the

leaves for transpiration the outlets from the woody meshed, spongy

parenchyma must not be obstructed, and it does not need further proof

that the evergreen rolled leaf is the form most suited and adapted to

these conditions."

In the Gothic translation of the Gospel, by

Ulfilas, he renders Matthew VI., 28, not by "consider the lilies of the

field," but by "consider the blooms of the Heath."

In Jeremiah XVII., 6, occurs the passage, "For he

shall be like the Heath in the desert." This reference bears out the

sense of the parched and fruitless existence of the Heath as it existed

to the ancient Greek; but the plant named in the Bible is given in the

Septuagint as the wild tamarisk. Relative to this matter, McClintock &

Strong's Encyclopedia states: "Heath; arar, has been variously

translated, as Myrica, tamarisk; tamarin, which is an Indian tree, the

tamarind; retama, that is, the broom; and also, as in the French and

English versions, bruyère, heath, which is, perhaps, the most incorrect

of all, though Hassecquist mentions finding heath near Jericho in

Syria."

In the Fagn-Kinsman Dictionary of the Bible, G. .

Post says: "One species of Heath, Erica verticiltata Forsk, grows on

sandstone and chalky rocks, at an altitude of from 300 to 3,500 feet, on

the w. face of Lebanon and the chains to the northward. This cannot be

the plant intended. There are no heaths in the desert."

|