|

N

the year of grace 1270 or thereabouts Sir Aymer Maxwell of Caerlaverock

granted to his third son, Sir John Maxwell, the lands of Nether Pollok

in the county of Renfrew, from whom the present owner, Sir John Stirling

Maxwell, is twenty-third in direct descent, through his grandmother, who

married Archibald Stirling of Keir. Six hundred and thirty-seven years

have wrought much change in nearly every part of King Edward's realm,

but nowhere has the landscape undergone more wholesale metamorphosis

within a like period than in the valley of the White Cart. N

the year of grace 1270 or thereabouts Sir Aymer Maxwell of Caerlaverock

granted to his third son, Sir John Maxwell, the lands of Nether Pollok

in the county of Renfrew, from whom the present owner, Sir John Stirling

Maxwell, is twenty-third in direct descent, through his grandmother, who

married Archibald Stirling of Keir. Six hundred and thirty-seven years

have wrought much change in nearly every part of King Edward's realm,

but nowhere has the landscape undergone more wholesale metamorphosis

within a like period than in the valley of the White Cart.

When Sir John Maxwell

took possession of his estate in the thirteenth century, Glasgow was a

modest hamlet, clustering round the brand-new cathedral of Bishop

Joceline; it has now overflowed upon 11,861 acres on both banks of the

Clyde, which winds through the municipal area for a distance of five

miles and a half.

It is not only the land

surface which has altered in appearance, forest and crag making way for

closely packed dwellings and factories; the Clyde and its lower

tributaries were allowed to become so foully polluted that a lifeless,

evil-smelling current flows where once the silvery salmon thronged up

from the firth and innumerable water-fowl flocked for food. That is in

process of being remedied by a painstaking municipality; but who shall

purge the sky of the smoke rising from the hearths of 780,000

inhabitants and the reek belched from a thousand factory chimneys and

gas-works?

Nor is that all that must

be reckoned. In a wide circle round Glasgow have arisen police-burghs

Kinning Park, Govan, Partick, Pollokshaws, Cathcart, etc.—each with a

population exceeding that of many a mediaeval city, each with its

smoke-producing industries, and only a little further afield is Paisley

with 87,000 inhabitants, Johnstone with 12,000, Port-Glasgow with

18,000, Greenock with 68,000, all combining to darken the air; and, as

though that were not enough to discourage horticulture, all the land

unbuilt on is threaded with railways, honeycombed with coal-pits,

studded with smelting furnaces, pouring forth volumes of smoke night and

day. So it has come to pass that from whatever quarter the wind sets, it

is charged with the products of combustion—in other words, with coal

smoke.

This, as every forester,

gardener and amateur can testify, is a relentless foe to almost every

kind of vegetable life. Strange to say, mosses and lichens, humblest in

the scale, succumb first, so that in all this region stones and tree

stems are devoid of that kindly covering which always gathers upon them

in a pure atmosphere. The next to suffer .are.. trees themselves; for

although many fine elms, beeches, oaks, sycamores, ash, and even pines

survive in this wide strath, these grew to maturity under conditions

very different from those now prevailing, and the growth of young trees,

especially conifers and oaks, is sorely checked and blighted by carbon

deposit and sulphurous fumes.

Nevertheless,

horticulture dies hard; the instinct of every man owning a garden is to

obey the primaeval command "to dress it and to keep it"; and Miss Wilson

has chosen a scene in the garden at Pollok as an example of what

combined skill and resolution may accomplish in the most forbidding

environment.

The subject of the

picture is a terrace wall, constructed only five or six years ago of

ashlar masonry, with slits purposely left between some of the joints for

the insertion of suitable flowering plants.

The park of Pollok is but

a green oasis round which Glasgow and the neighbouring burghs have

flowed like a dark and rapidly rising tide. Yet here, on this terrace

wall, within constant sound of steam hooters and whistles, steam hammers

and pumps, you may see alpine flowers blooming as profusely and with

colours as clear as they do on the loftiest solitudes on earth and in

the purest atmosphere. The chief display when this picture was

painted—in May—came from the varieties of Aubrietia with their hanging

cushions of purple and mauve, and golden Alyssum. Common things, these,

yet priceless in their effect and unfailing in the reward they make for

attention to their simple wants. A month later, the purple and gold had

been dimmed; a rose-coloured mist had spread along the wall, created by

different kinds of dwarf Dianthus and Silene, with the common sea-thrift

of our shores; while through the mist shone stars of Arenaria and many

species of saxifrage and stonecrop. Dwarf bell flowers, also, spread

blue curtains over the stones, among the most effective being the

glaucous variety of Campanula garganica, known as hirsuta, C. pusilla

and the hybrid "G. F. Wilson," C. muralis, which must now be sought for

under the preposterous title of C. portenschlageana.

All these are anybody's

flowers, anybody's, that is, who has the wit to raise them from seed,

for they are not particular as to soil (though most of them show

gratitude for an admixture and occasional top-dressing of old lime

rubbish), or climate, as their luxuriance in this Glasgow atmosphere

amply testifies. But among these commoner things are herbs, if not of

greater beauty, of greater rarity. Specially to be commended are the

little Himalayan Potentilla nitida, with silvery leaves and delicate

flesh-coloured flowers, like miniature Tudor roses; Myosotis rupicola,

an exquisite forget-me-not which likes to be wedged tightly into a rock

crevice; our native purple saxifrage S. oppositifolia, the

golden-flowered S. sancta from far Mount Athos, the fragrant S.

apiculata, thickly set with panicles of sulphur-coloured blossoms,

exactly the hue of a wild primrose, in early spring; and, earliest and

finest of all, the snowy-petalled S. Burseriana. Then the encrusted

section of rock-foils, bewildering in variety, delight in such a

position, growing into such exquisite bosses and wreaths that one almost

grudges the profusion of their bloom, which conceals the delicate

carving of their foliage.

It is wonderful how

readily these and other mountaineers adapt themselves to their

unpromising environment. The truth is that, like the red deer, they have

taken to the mountain tops because they have been crowded out of the low

country, where they were overwhelmed in competition with other herbs; so

they survive only in places where their constitution enables them to

endure conditions unfavourable to rank vegetation. A notable and

oft-quoted example of this is the common thrift, which is found all

round our coasts at sea level and on the summits of some of our highest

mountains, both these situations being unfavourable to the majority of

lowland vegetation; but one may search in vain for a single specimen of

thrift between these two extremes. That it would thrive anywhere is

proved by the ease with which it may be cultivated in gardens at any

level; cultivation, in this instance, amounting to no more than the

suppression of competing vegetation. In planting a terrace wall like

that at Pollok it is necessary to raise seedlings or cuttings which may

be inserted while still small in the crevices of the masonry. After

being settled in their places they drive their roots to almost

incredible distance into the solid earth behind the wall, which protects

them alike from summer drought and trying variations of temperature iii

winter, while the vertical surface ensures rapid drainage and protection

from frost.

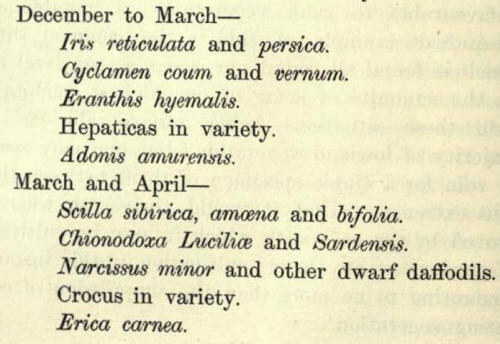

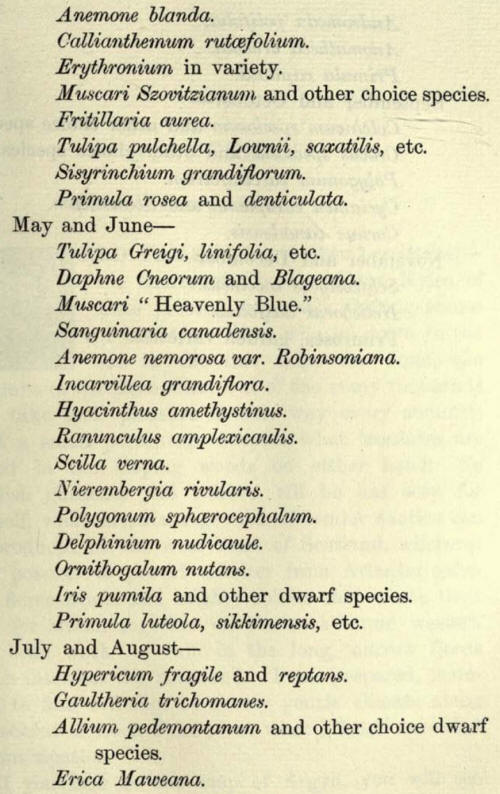

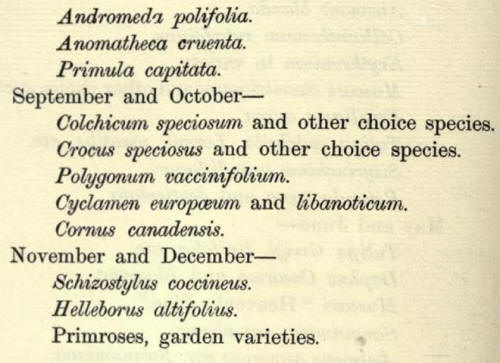

The narrow border at the

wall-foot provides a congenial home for choice bulbous and other plants,

which, if carefully selected, may keep up a continuous display almost

throughout the year. The list of suitable plants for this purpose might

be made a long one. The following one contains suggestion for a small

collection which may be added to at pleasure, suitable for a northerly

climate.

|