|

HE

whole plan and purpose of this book being to illustrate types of

Scottish horticulture, the grandiose and elaborate have received no

preference over the unpretending and simple. Any space of Scottish soil,

be its dimensions calculable in roods or in acres, will serve our turn,

so that it be an abode of flowers well tended, or at least, unspoilt, by

its owner. HE

whole plan and purpose of this book being to illustrate types of

Scottish horticulture, the grandiose and elaborate have received no

preference over the unpretending and simple. Any space of Scottish soil,

be its dimensions calculable in roods or in acres, will serve our turn,

so that it be an abode of flowers well tended, or at least, unspoilt, by

its owner.

Simple, indeed, is the

garden design at Gartincaber—a plain rectangle sloping pleasantly to the

sun; at the upper-end a sixteenth century tower, with nineteenth century

additions naively contrived; at the lower-end a clear pool, not ample

enough to aspire to the title of "loch," yet, shadowed by dark firs on

the far side, too comely to bear the common Scottish term "a stank."

This walled enclosure is laid out in the old manner, subdivided by

crossed paths, with a sun-dial at the crossing; kitchen herbs and small

fruits in the four quarters,

with narrow selvage of

flowering things, overhung here and there by aged apple trees. Nothing

can have been further from the designer's intention than landscape

effect: use, not ornament, was his purpose, flowers being admitted in

grudging concession to feminine frivolity ; but age has brought about

delectable results—age, and the affectionate tending of generations.

Lofty holly hedges, such as John Evelyn praised, screen the litter in

such corners where litter must be; a few massive sycamores add dignity

to the scene in winter and shade from summer heat, without, as it seems,

impoverishing the borders, for these teem with blossom to the very feet

of the trees. But they are flowers of modest requirements—winter

aconites and snowdrops, daffodils and wind-flowers, bloodroot, violets

white and purple, primroses and oxlips of many hues—all old friends, the

older the better to be loved. On this mid-April morning in a late—a very

late—season, what strikes one as most notable is the abundance of double

white primroses on usually long footstalks, surely a strain peculiar to

the place.

I have dwelt on the

simplicity of this garden, but every yard of it bears witness to

affectionate care, and in one respect this affection has evinced itself

in a manner reflecting agreeably the classical taste of a bygone age.

Thus at the foot of the slope has been placed a wide stone bench,

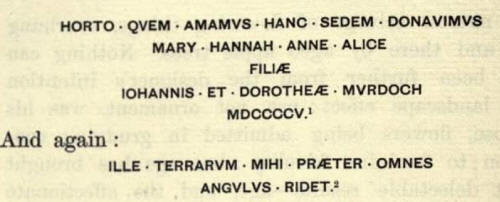

whereof the back bears this inscription:

The sun-dial in the

middle of the garden is also inscribed with many legends, and bears on

its base a dedication to Mr. and Mrs. Burn-Murdoch "on their golden

wedding," from their grandchildren, Lorna, Dorothea, Ian, Marion, and

Colin.

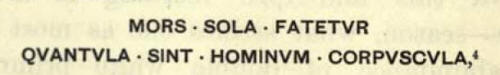

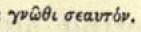

It is no modern trait in

the family, this pretty taste for inscribing stones. During the four

centuries or thereby it has stood, the house of Gartincaber has owned no

other lord than a Murdoch, and the dormer windows bear legends in

relief; on one, NOSCE TEIPSVM 3, surmounted by a thistle; on

another a tag from Juvenal:

under a man with a bent

bow.

1. Mary, Hannah, Anne,

Alice, daughters of John and Dorothy Murdoch, have presented this seat

to the garden which we love. 1905." Horto nobis dilecto had been a more

graceful rendering.

2 "This little corner

pleases me better than all the world beside." Horace, Odes ii. 6.

3"Know thyself"—the Attic

. "Oh Athenians, your wisdom

reaches us across the centuries! We hear your murmured messages—' Know

thyself,' `Nothing in excess!' We who have travelled so far, and yet so

little, we who are still scaling the heights you reached—Athenians, we

salute you!" . "Oh Athenians, your wisdom

reaches us across the centuries! We hear your murmured messages—' Know

thyself,' `Nothing in excess!' We who have travelled so far, and yet so

little, we who are still scaling the heights you reached—Athenians, we

salute you!"

The Diary of a Looker-on,

by C. Lewis Hind.

4 " Death alone discloses

how feeble are the bodies of men."—Juvenal, Sat. x, 173.

may have been inspired by

the haughtiness of some affluent neighbour ; the lord of Doune, perhaps,

whose great castle, though now in ruins, still scowls defiance from the

further shore of Teith.

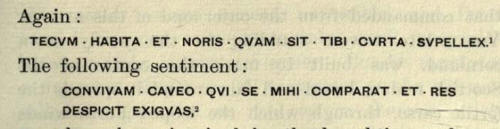

Even the latest addition

to the old house bears its appropriate legend, the gable of the new

drawing-room bearing one well expressing the spirit which has attached

this family to its ancient home:

I - DWELL - AMONG • MY -

OWN - PEOPLE, 3

Of the two avenues which,

planted at right angles to each other, lead up to the house, the

northern, consisting of two double rows of beeches, has been sorely

wrecked by gales, but the west avenue is still intact, a remarkable and

far-seen feature in the landscape. Running along the comb of a ridge, it

is composed of lime trees which appear to be about 100 or 120 years old.

The two rows are only fifteen feet apart; and the trees, set very

closely in the rows, have been drawn up to the height of a hundred feet.

There is no nobler prospect in Scotland, none richer in historic

association, than

1. "I Live by yourself, and

you will find out how ill-furnished is your mind." Persius, iv. 52.

2 "I am on my guard

against the guest who draws comparisons between himself and me, and

contemns my slender means."

3 Kings iv. 13.

that commanded from the

outer end of this avenue. Yon white tower, standing in the newly sown

cornland, was built to mark the centre of the Scottish realm; broad and

fair around it spreads the fertile cause, through which the looped Forth

winds its leisurely way. You may trace its gleams till they are lost in

the blue haze on the east, where the sunlit Ochils, Stirling Castle, and

Polmaise woods arrest the eye, only a little nearer than blood-boultered

Bannockburn and Falkirk. All along the southern horizon stretch the

flat-topped Lennox Hills and Campsie Fells, their outline presenting

marked contrast to the tumultuous range on the north, where Ben Ledi and

Stuc-a'chroin still wear their snowy hoods. Far on the west Ben Lomond

rears its cloven cone, commanding outpost of the Highland host. Every

feature in the landscape has its story for the understanding eye, from

northward Ardoch, where Julius Agricola has left enduring memorial of

his conquest in the earthen ramparts of his camp, to nearer Kippen on

the south, where Prince Charlie's Highlanders crossed the Ford of Frew

when last Great Britain felt the throes of civil strife.

A word about the Murdochs

of Gartincaber. They trace their descent from one Murdoch, who rendered

yeoman service to Robert the Bruce in his hour of need. In the early

spring of 1307, the King of Scots was hiding in the Galloway hill

country with a few hundred followers. King Edward's troops beset all the

passes: escape seemed impossible, and Bruce caused his men to separate

into small companies, so as to make subsistence easier. But he appointed

a day when they were all to muster at the hill now called Craigencallie,

on the eastern shore of lonely Loch Dee. Here, in a solitary cabin,

dwelt a widow, [The name Craigencallie signifies in Gaelic "the old

woman's crag," and is cited in evidence of the truth of the legend.] the

mother of three sons, each by a different husband, and named Murdoch,

Mackie and MacLurg.

The King arrived first,

and alone, at the rendezvous. Weary and half-famished, he asked the

widow for some food ; nor asked in vain, for, said she, all wayfarers

are welcome for the sake of one. "And who may that one be?" asked the

King.—"None other than Robert the Bruce," quoth the goodwife, "rightful

lord of this land, wha e'er gainsays it. He's hard pressed just now, but

he'll come by his own, sure enough."

This was good hearing for

the King, who made himself known at once, was taken into the house and

sat down to the best meal he had eaten for many days. While he was so

employed, the three sons returned, whose mother straightway made them do

obeisance to their liege lord. They declared their readiness to enter

his service at once, but the King would put their prowess as marksmen to

the test before engaging them. Two ravens sat together on a crag a

bowshot off; the eldest son, Murdoch, let fly at them and transfixed

both with one arrow. Next, Mackie shot at a raven flying overhead, and

brought it to the ground, and the King was satisfied, although poor

MacLurg missed his mark altogether.

In after years, when the

widow's words had been fulfilled by Bruce coming to his own and being

acknowledged King of Scots, he sent for the widow and asked her to name

the reward she had earned by her timely hospitality.

"Just gie me," said she,

"you wee bit hassock o' land that lies atween Palnure and Penkiln"—two

streams flowing into Wigtown Bay.

The King granted her

request. The "bit hassock," being about five miles long and three broad,

was divided between the three sons, from whom descended the families of

Murdoch of Cumloden, Mackie of Larg, and MacLurg of Kirouchtrie.

Cuniloden remained the property of the family of Murdoch till 1738, when

it was sold to the Earl of Galloway to discharge an accumulation of

debt. The fine shooting of the founder of the family is commemorated in

the arms borne by his descendants, and duly enrolled in the Lyon

Register, viz., Argend, two ravens hanging palewise, sable, with an

arrow through both their heads fess-wise, proper.

In the Justiciary Records

of Scotland there is brief record of a horrible outrage perpetrated upon

Patrick Murdoch of Cumloden in 1605. Robert and John, sons of Peter

M`Dowall of Machermore, a near neighbour of Cumloden, were arraigned

upon a charge of having seized Murdoch and his servant Peter M'Kie, and

cut off their right hands. Peter M`Dowall was accepted as surety for his

sons, who were liberated on their father's undertaking that they would

appear for trial at Kirkcudbright, after receiving fifteen days' notice.

But the M'Dowalls were a powerful clan. When the case was called at the

assizes, a jury could not be empannelled, twenty-seven persons who were

summoned preferring to pay the statutory fine rather than serve ; and we

hear no more either of the malefactors or their victims. |