|

N

all the west no fairer prospect can be had than is commanded by one

standing above the pretty little watering place of Fairlie on the Firth

of Clyde. I have studied it at all seasons and in all moods of weather:

beshrew me if I can tell which becomes it best—a clear winter day, when

the fantastic fairyland of Arran gleams snow-clad beyond the blue-waters

in almost unreal splendour —a summer morning, when the sea lies pearly

calm and the eastern rays reveal every glen and corrie, every shattered

peak and shadowed cliff in the brotherhood of Goat Fell,—or again in

September, when that outline whereof the eye never wearies is cast in

purple, clear-cut silhouette against the saffron west, while the dusky

isles of Cumbrae and Bute fill in the quiet middle distance. In all its

aspects it is a perfect landscape, and although the lord who built his

tower in the sixteenth century on the brink of Kelburne Glen, may have

had in view strategic rather than aesthetic considerations, it happened

here, as it has happened in many another instance, that both purposes

were best secured on the same site. N

all the west no fairer prospect can be had than is commanded by one

standing above the pretty little watering place of Fairlie on the Firth

of Clyde. I have studied it at all seasons and in all moods of weather:

beshrew me if I can tell which becomes it best—a clear winter day, when

the fantastic fairyland of Arran gleams snow-clad beyond the blue-waters

in almost unreal splendour —a summer morning, when the sea lies pearly

calm and the eastern rays reveal every glen and corrie, every shattered

peak and shadowed cliff in the brotherhood of Goat Fell,—or again in

September, when that outline whereof the eye never wearies is cast in

purple, clear-cut silhouette against the saffron west, while the dusky

isles of Cumbrae and Bute fill in the quiet middle distance. In all its

aspects it is a perfect landscape, and although the lord who built his

tower in the sixteenth century on the brink of Kelburne Glen, may have

had in view strategic rather than aesthetic considerations, it happened

here, as it has happened in many another instance, that both purposes

were best secured on the same site.

The central tower of

Kelburne Castle is dated 1581. It may have been built—probably was soon

the site of an earlier keep—but it was not many years old when Timothy

Pont, to whom we owe such an intimate knowledge of Scottish topography

before the union of the Crowns, described it in the following words."

Kelburne Castell, a goodly building veill planted, hauing werey beutiful

orchards and gardens and in one of them a spatious Rome adorned with a

chrystalin fontane cutte all out of the living rocke. It belongs

heretably to Johne Boll [Boyle] Laird thereof."

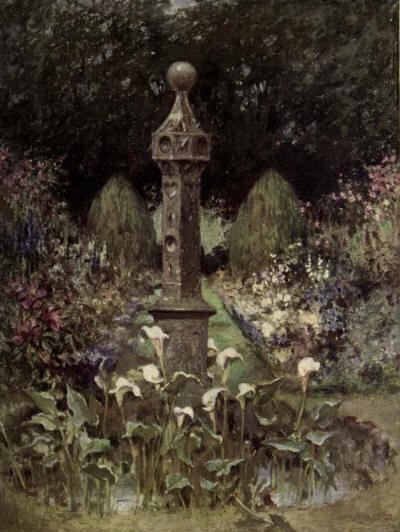

The gardens remain,

enriched with the dignity that only centuries can confer; but the "spatious

Rome [?room] "—where is it? Miss Wilson's drawing shows a circular stone

basin, wherein stands, not a fountain, but a wonderful sundial, wrought,

apparently, by the same hand as one dated 1707 which stands near the

house. The surmise of the present "Boll "—to wit, David, seventh Earl of

Glasgow—is that when David, the first Earl, was adding to the house and

had the dated sundial erected there, he was so well pleased with it that

he had a second one made and substituted it for the "chrystalin fontane."

Be that as it may, one has no reason to complain of the result, so

admirably does this old dial, stained and mellowed by the time which it

was set there to measure, harmonise with

the old-world borders,

the paths of smooth sward and the ancient yews which seem to set time at

defiance. Nobody now notes the shadow of the gnomon, for every man

carries a time-keeper in his pocket, and ladies, who have no pockets,

bind untrustworthy watches on their wrists or pin them on their bosoms;

but we are none of us the worse of the warning conveyed by this grey

column in a pleasure ground, which seems to echo the old Scots saw-

[Take heed of time ere it be beyond recall.]

A charming example is

Kelburne of Scots building of the sixteenth century, the original tower

of "Johne Boll " standing clear, unimpaired, and unmutilated by the

first Earl's addition. On the south-west front of it is the old herb

garth enclosed in high walls, now converted into a pleasaunce, with

flower beds and shrubberies lying fair to the sun, with the broad waters

of the firth shimmering beyond. Shady alleys run round the enclosure,

not laid with crunchy gravel but with greensward of seductive texture,

bordered with shrubs, among which are just so many of the choicer kinds

to cause one to wish for more. Rhododendron Thomson and campanulatum are

each over 12 feet high; the common myrtle forms a great bush without the

protection of a wall; samples these of what a rare collection might be

ranged here if some of the common stuff were cleared away. In one of the

gardens in the town of Fairlie I noticed Cordyline auatralis twenty feet

high; what then might not be made of this fine enclosure with its kindly

sheltering walls if the space occupied by aucuba and clipped Portugal

laurel were devoted to some of the host of lovely things that delight in

a western climate—such as Carpenteria, Desfontainea, Eucryphia and

Himalayan rhododendrons? Also one grudges the wall space covered with

masses of ivy, for the masonry might be draped with many forms of

beauty, too tender to stand alone.

A curious enclosure, some

thirty feet square, with high walls, stands at one corner of this

pleasaunce. It is roofless now, but appears to have been once a pavilion

or large summer house. The entrance is through a pretty wicket of

wrought iron, and the interior is occupied by Lady Glasgow's rock

garden, a delightful nook for the cultivation of choice flowers and

ferns. The more modern kitchen garden has broad borders backed with

rose-covered pergolas and filled with a general herbaceous collection,

well-ordered and in excellent condition. Conspicuous in early July were

two varieties of dittany (Dictawnnus fraxinella) of a brighter rose tint

than I have seen elsewhere, a great improvement on the ordinary type,

which is not very satisfactory in colour. A bright myosotis was very

pleasing. I took it at first for the hybrid of azorica named "Imperatrice

Elizabeth," but the gardener informed me it was called "Queen Victoria."

Before going up the glen

one pauses to admire a splendid specimen of Pinus insignis, of unusually

erect and graceful habit. Judged by the eye, it must be between 90 and

100 feet high, and the tape gave its girth as 15 feet at 4 feet above

the ground. Among all the pines there is none to be so highly prized as

this for its dense, rich green foliage, distinguishing it in winter from

every other evergreen.

The glen is one of the

chief attractions of the place, though here again one longs to

substitute tree ferns and rare rhododendrons for some of the tangle of

R. ponticum and native undergrowth. The burn has tunnelled its way

through the soft red sandstone close to the house; a natural cascade

fills the air with ceaseless sound—a gentle tinkle in summer heats, a

thunderous rush in autumn spates. Paths line the cliffs on either side

the stream: one of them leads to a grove of lofty silver firs, amid

which is set a tablet to the memory of John, Earl of Glasgow (d. 1755),

to the narrative of whose prowess some ambiguity is imparted by

uncertainty of punctuation. Thus

"At the Battle of Fontenoy

Early in Life,

he lost his Hand and his Health His

Manly Spirit, not to be subdued, at Lafield

he received Two Wounds in one Attack."

Lord Glasgow observes a

commendable practice in displaying his own arms from the flagstaff on

the tower, and nobly does the scarlet eagle, double-headed on a yellow

field, flaunt in the breeze, in high relief against a dark background of

hanging woods. It would add greatly to the interest of a countryside

were other landowners to follow his example, each hoisting the heraldic

bearings to which he is entitled; for deeply as we revere the flag which

is famed (with scant historical accuracy) for having "braved a thousand

years the battle and the breeze," it loses some of its significance when

it is flown from any public house or tea-garden. |