|

HE

Ythan, beloved of trout-fishers, flows through a fair strath enriched

with many memories and set with many an ancient fortalice. Transcending

all others in Aberdeenshire—perhaps in all Scotland—for architectural

interest is the magnificent castle of Fyvie, whereof the history has its

source in days long before Edward I. of England made it his lodging in

1296, and bids fair to outlast by many centuries the visit of Edward

VII. of Great Britain and Ireland (and a good deal else besides) in

1907. When the annals of a house extend over so many centuries, trifling

chronological inexactitudes may be treated with leniency; still, it

taxes our credulity rather beyond its limits to be shown in the

fifteenth century Seton tower at Fyvie the actual bedroom occupied by

the first Edward in the thirteenth century! In truth, there is no part

of the building which can be declared confidently to have belonged to

the original stronghold, so completely has the whole castle undergone

reconstruction by successive HE

Ythan, beloved of trout-fishers, flows through a fair strath enriched

with many memories and set with many an ancient fortalice. Transcending

all others in Aberdeenshire—perhaps in all Scotland—for architectural

interest is the magnificent castle of Fyvie, whereof the history has its

source in days long before Edward I. of England made it his lodging in

1296, and bids fair to outlast by many centuries the visit of Edward

VII. of Great Britain and Ireland (and a good deal else besides) in

1907. When the annals of a house extend over so many centuries, trifling

chronological inexactitudes may be treated with leniency; still, it

taxes our credulity rather beyond its limits to be shown in the

fifteenth century Seton tower at Fyvie the actual bedroom occupied by

the first Edward in the thirteenth century! In truth, there is no part

of the building which can be declared confidently to have belonged to

the original stronghold, so completely has the whole castle undergone

reconstruction by successive

owners. Nevertheless it

remains almost without a rival as an example of the peculiar Scottish

style.

So sweetly the woods and

fields smile under the fleecy clouds, so blue are the hill-crests and so

sparkling the streams, that we cannot grudge the hours as the leisurely

"local" wends its way from Aberdeen on this perfect summer day. In due

time we alight (in literature people do not "get out" of trains and

carriages, they "alight") on the platform of Fyvie station. There is a

choice of ways thence to our destination—the legitimate one by the high

road, but that has been robbed of much of its charm by the interminable

park wall which Lord Leith of Fyvie recently caused to be built for the

relief of the unemployed; so we take the other, illegitimate perhaps, to

mere wayfarers as we are, but Scottish landowners are never illiberal in

the matter of trespass. Entering the "policies" of Fyvie at the lodge

gate, a delightful woodland walk leads across the little river, under

the walls of the castle and out along the margin of a lake till we reach

the open country again.

Below us on the right is

the bridge of Sleugh where Annie of Tifty Mill [Her baptismal name was

Agnes, but she always appears as Nanuie or Annie in the various versions

of the ballad.] parted for ever with her lover—a tragedy commemorated in

a ballad which became dearer, perhaps, than any other to Aberdeenshire

people. It tells how pretty Agnes, daughter of the wealthy miller of

Tifty, lost her heart to a handsome trumpeter in the suite of the Lord

of Fyvie.

"At Fyvie's yett there

grows a flower,

It grows baith braid and bonnie;

There's a daisy in the midst o' it,

And they call it Andrew Laramie."

No backward lover was the

said daisy, for the maiden tells us how

"The first time me and my

love met

Was in the woods o' Fyvie,

He kissed my lips five thousand times

And aye he ca'd me bonnie."

The miller, whose name

does not appear in the poem, but who is known to have borne the homely

one of Smith, took a very firm line with his daughter from the first. He

declined even to entertain the idea of her wedding with a mere

trumpeter. She should look far higher for a mate with her " tocher " of

five thousand merks. The miller's wife and sons were of the same

opinion, and between them they led poor Annie a terrible life. If the

poet is to be credited, when argument failed, they tried violence and

beat the girl unmercifully. They even showed Lord Fyvie the door when he

came to plead the cause of the lovers. Annie remained true to her troth,

and before Andrew's duty called him away to Edinburgh he met her in a

last tryst at the Bridge of Sleugh, and vowed he would come back and

marry her in spite of them all.

Now there is an old

Scottish belief that lovers who part at a bridge will meet never more ;

and so it proved with this fond couple. Annie died, some say of a broken

heart, others of a broken back owing to her brother's brutality.

"When Andrew hame frae

Embro' cam

Wi' muckle grief and sorrow

'My love is dead for me to-day,

I'll die for her to-morrow.

"'Now will I speed to the

green kirkyard,

To the green kirkyard o' Fyvie;

With tears I'll water my love's grave,

Till I follow Tifty's Annie.'"

No doubt was ever cast on

Andrew's fidelity; but although he may have mourned over his

sweetheart's grave, he did not stay in the kirkyard, for it is told of

him that long after her death he was in a company in Edinburgh where the

ballad of Tift/s Annie was sung, which so deeply affected him that the

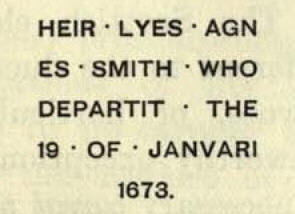

buttons flew off his doublet! A stone in "the green kirkyard of Fyvie"

bears the following inscription:

while Andrew Lammie is

commemorated by a stone figure of a trumpeter on the battlements of one

of the castle towers.

But our errand to-day is

not to gather up on the spot the threads of this sad story, nor to view

the lordly castle, nor yet to explore the foundations of S. Mary's

Priory, built by Fergus Earl of Buchan in 1179 for the Tironensian monks

of S. Benedict, or to deplore the completeness of its demolition. There

stands the castle, but there does not stand the priory, though its site

is well marked by a tall Celtic cross, set up in 1868 on a green knoll,

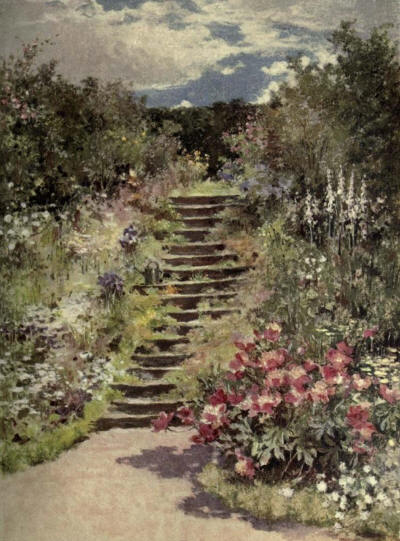

and far seen up and down the strath. The object of our mission lies

close to "the green kirkyard of Fyvie," whither Miss Wilson's instinct

for fair flowers directed her, with the result shown in Plate XIX.

A keen instinct it is

shown to be, for it is a melancholy but general truth that the manse

garden is about the last place in a Scottish parish that one expects to

find well-tended borders. Iu England it is different; it is among the

English clergy that you may look for some of the most accomplished

amateurs, and, as high authorities in horticulture, it would be hard to

beat Dean Hole for roses, Mr. Engleheart for daffodils, or Canon

Ellacombe for all sorts of flowering things. The Scottish clergy, as a

class, are strangely indifferent to the fluctuating hopes and fears,

joys and woes, of horticulture. There are notable and praiseworthy

exceptions, but I speak of the class, with the necessary caveat about

generalising. I scarcely think that our pastors of to-day can be

deterred from seeking solace in an occupation so natural and congenial

to men whose avocation keeps them in country homes throughout most of

the months, or that they have any such apprehension of censure as

induced good Dr. Nathaniel Paterson seventy years ago to withhold his

name from the title-page of the first edition of his delightful Manse

Garden.

"The following work," he

explained in the introduction, "though nowise contrary to clerical duty,

is nevertheless not strictly clerical ; and as nothing can equal the

obligation of the Christian ministry, or the awe of its responsibility,

or its importance to man, the writer trembles at the thought of

lessening, by any means or in any degree, either the dignity or the

sacredness of his calling; and as the following pages might more

properly have been written by one bred to the science of which they

treat, or by some leisurely owner of a retired villa, an inference, not

the best matured, may be drawn to the effect—that surely the Author can

be no faithful labourer in the Lord's Vineyard, seeing he must possess

such a leaning to his own. He therefore expects, by hiding for a little,

to give the arrow less nerve, because the bowman can only shoot into the

air, not knowing whither to direct his aim."

It may be deemed

presumptuous for a layman to criticise the recreations of his spiritual

masters. Assuredly I do so in no carping spirit, but out of sheer

concern for the neglect of so harmless and convenient a hobby. For is

not every man happier with a hobby? And in riding this particular hobby

gently, a country clergyman may lead the way for his parishioners to do

the like. Hear what comfortable words the aforesaid Dr. Paterson spoke

upon this matter.

"When home is rendered

more attractive, the market-gill will be forsaken for charms more

enduring, as they are also more endearing and better for both soul and

body. And 0! what profusion of roses and ripe fruits, dry gravel and

shining laurels, might be had for a thousandth part of the price given

for drams . . . Thus external things, in themselves so trivial as the

planting of shrubs, are great when viewed in connection with the moral

feelings whence they proceed and the salutary effects which they

produce... Wherever such fancy for laudable ornament is found (and it is

a thing which, like fashion, spreads fast and far), the pastor, by

suggesting this guide to simple gardening, may do a kindness to his

flock."

Now let me descend from

the pulpit which I have usurped, and enter the manse garden which I have

brought the reader so far to see. Favoured by fortune as few gardens of

this class have been, it has passed successively through hands which

have carefully tended it. Various stories are told to account for the

amplitude of the kitchen garden and the high walls enclosing it.

According to one version, these walls were the gift of his wife to a

former incumbent, Mr. Manson, and, scarcely was the mortar dry in them

when the Disruption of the Kirk came to pass (in 1843), and Mr. Manson

"went out," surrendering his benefice and forsaking his beloved

garden—for conscience' sake. Another variant attributes these walls to

another lady, wife of the Rev. John Falconer, who was minister from 1794

to 1828, immediate predecessor of the aforesaid Mr. Manson. After Mr.

Manson's resignation, Dr. Cruikshank was translated from Turriff to

Fyvie, and married Mr. Falconer's widow, thus inheriting the walls.

[Mrs. Cruikshank is buried in the apse of the parish church between her

two husbands.] Dr. Milne followed Dr. Cruikshank in 1870, and there

remains ample ocular evidence to the pleasure he took in his borders

during his ministry of five and thirty years. By him and his family the

garden was greatly enriched with a pretty extensive collection of shrubs

and herbaceous and alpine plants.

And now, in the person of

the Rev. G. Wauchope Stewart the garden owns a new incumbent who is not

too proud to take honest pride in fruits and flowers of his own raising,

or to soil his hands with spade labour. Under his care and that of Mrs.

Stewart there is no fear that the well-stocked garth will be

impoverished or that the borders will be allowed to run wild. Much and

sedulous attention is required, for the grounds are full of nooks and

unexpected spaces, each with its store of choice things. Specially

deserving of thoughtful tending is a bit of wall garden—"a garden of

remembrance"—where saxifrages of many sorts, stonecrops, Rarynondia,

bellflowers, and other pretty flowers are well established —gifts from

friends to the departed pastor and his family. Sure no fitter or more

touching remembrance can be devised than these lowly herbs, for is not a

flower the true symbol of the resurrection? And does not each one,

re-appearing season after season, seem to breathe the prayer—"Will ye no

come back again?"

Before leaving Fyvie,

leave should be obtained to enter the parish kirk to view a truly

beautiful west window which has been placed there to the memory of Lord

Leith of Fyvie's only son, a subaltern in the Royal Dragoons, who died

in service in the South African war in 1900, aged only nineteen. This

window is quite the most beautiful bit of modern stained glass I have

seen in any country, and its effect is enhanced, if anything, by the

surprise of finding such a fine work of art in a building which,

externally, is very unpromising. |