|

The production of both

jellies and marmalades depends on the same principles, and the methods

of manufacture are similar. For these reasons they have been discussed

together in this chapter.

The following paragraphs

give the fundamental principles as well as a discussion of various tests

for jelly.

These enable anyone at

all familiar with cooking to obtain uniform results.

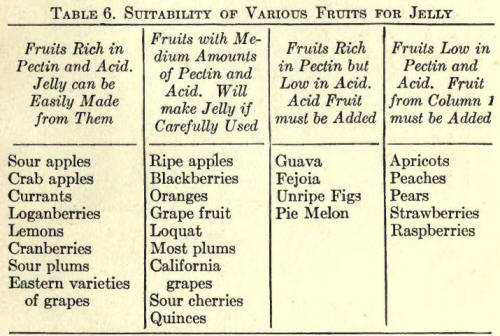

38. Fruits for Jelly.

A fruit jelly depends for its consistency upon three substances. These

are pectin and acid, from the fruit, and sugar, which is added. If any

one of the three components is lacking or too small in amount, jelly

cannot be made.

Certain fruits are rich

in both pectin and acid. Examples are sour apples, crab apples,

currants, loganberries, and lemons. Jelly is easily made from these

fruits. Some fruits contain moderate amounts of pectin and acid.

Examples are loquats, oranges, ripe apples, blackberries, grape fruit,

and some varieties of plums. Jellies can be made from these fruits if

care is taken. Some fruits are rich in pectin but low in acid. The

guava, quince, and fejoia are examples. Acid fruits must be added to

such fruits. Other fruits are low in pectin but rich in acid; for

example, rhubarb and gooseberries. Still other fruits are deficient in

both acid and pectin. Peaches, apricots, prunes, pears, strawberries,

and raspberries belong to this class. They must be combined with such

fruits rich in pectin as currants, crab apples, or sour apples, before

jelly can be made from them.

39. Preparing and Cooking the Fruit.

The fruits are prepared for cooking by cutting in pieces or by crushing.

Berries and currants should be crushed. Other fruits are cut.

The pectin is held in the tissues of the

fruit and in most cases must be liberated by boiling. Jellies can be

made from currants, loganberries, and cranberries by using the juice

obtained by crushing and pressing the fresh fruit without cooking, but

even these soft fruits give firmer jellies if boiled before extracting

the juice. In

cooking the fruit, water must be added to the less juicy varieties, such

as apples, plums, etc. Only enough should be added to barely cover the

fruit; if too much is added the juice will be too dilute and failure

will result. Currants, grapes, and berries need no added water.

The fruits should be cooked only until

tender. For apples this will be ten to fifteen minutes' boiling. Berries

should only be heated to boiling. Oranges, lemons, and grape fruit are

tough and require about an hour's boiling. Long boiling of any fruit

results in loss of flavor.

40. Expressing and Clearing the Juice.

The hot juice may be pressed from the fruit or may be allowed to simply

drain from the fruit through a cloth. The latter method is usually

employed in the household. In factories the juice is pressed from the

hot fruit with heavy pressure. If the juice is merely allowed to drain

from the fruit through a jelly bag it will be clearer than if obtained

by pressure, but pressing will give a larger yield of juice and the

juice will contain more pectin. Both methods may be combined by allowing

most of the juice to drain from the fruit through a jelly bag, followed

by pressing out the juice from the residual pulp in a small press or by

twisting the jelly bag to exert pressure. Juice obtained by pressure

must be filtered through a bag several times to clear it. If this is

done, very clear bright jelly can be made from it.

All fruit juices for jelly making should be

made as clear as possible by straining or filtering.

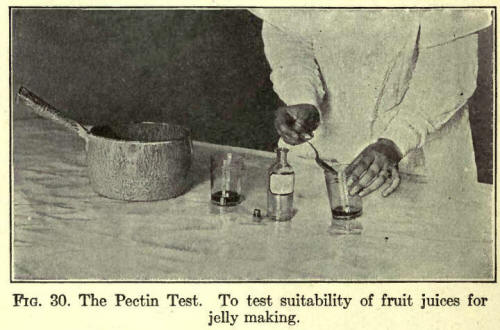

41. Testing for Pectin. If any doubt

as to the, jelling properties of the juice exists, it should be tested

for pectin. Failure can often be averted by this test.

Obtain a small amount (a ten cent bottle) of

grain alcohol from the druggist. To one teaspoonful of the juice in a

glass add one teaspoonful of the alcohol and stir slowly. If the juice

is rich in pectin, a very large amount of bulky gelatinous material will

form in the glass, almost turning the material to a soft jelly. Juices

moderately rich in pectin will give a few large pieces of gelatinous

material and juices too poor in pectin to make jelly will give a few

small flaky pieces of sediment.

If the juice proves poor in pectin it must

be blended with a juice rich in pectin. See paragraph 43 for the amount

of sugar to add to the juices of various pectin content. The less pectin

the fruit contains the less sugar can be used.

42. Testing for Acid. Fruits rich

enough in pectin to give a good jelly may not possess enough acid. No

accurate simple household method can be given, although the following

test will aid in judging of the acidity of the juice.

To one teaspoonful of lemon juice add nine

teaspoonfuls of water, and one-half teaspoonful of sugar. Mix in a

glass. Place in another glass a little of the fruit juice, but add no

water to it.

Compare the tartness of the two liquids by taste. If the fruit juice is

not as sour as the diluted lemon juice it is deficient in acid and it

will be necessary to raise the acidity of the fruit juice by adding

lemon or other sour juice.

With a little practice and experience this

test can be made very useful, although it is, of course, not very

accurate. 43.

Addition of Sugar. The amount of sugar to add to the juice will vary

with the pectin and acid content of the fruit. Juices such as

loganberry, currant, crab apple, and sour apples, that are rich in acid

and pectin, will make good jellies if one cup or as much as one and

one-quarter cups of sugar are used to each cup of juice. In some cases

as much as one and one-half cups of sugar can be used.

With fruit juices only moderately rich in

pectin, but still of fair jelling quality, three-fourths of a cup of

sugar may be used and with fruits low in pectin, only one-half a cup of

sugar may be used.

The reason for using less sugar with fruits poorer in pectin is seen

from the following discussion. To make jelly, the juice must finally

contain a high amount of sugar (55 to 65%), and enough pectin and acid

to form a jelly with the sugar. Boiling the juice after adding the sugar

concentrates the pectin by boiling off the excess water. The boiling

must continue until the jelly contains 55% or over of sugar. The more

sugar is added the less boiling is necessary and for the same reason the

less concentrating of the pectin in the juice takes place. If a small

amount of sugar is added, more boiling down is necessary to produce the

requisite high concentration of sugar and this results in greater

boiling down and concentrating of the pectin. Thus, if to a cupful of

juice poor in pectin only a half cupful of sugar is added the juice must

be boiled down to a relatively small volume and this will so increase

the pectin in proportion to the sugar that a jelly will usually result.

The sugar may be added cold as there is no

special virtue in warming it.

44. Sheeting Test for Jelling Point.

The juice and sugar should be boiled down rapidly in shallow pots. Long

boiling, such as is necessary in large amounts in deep pots, results in

loss of flavor, darkening of color, and caramelization of the sugar.

The juice must be boiled down until it will

jell when cold. This will be between 55 and 65% or more sugar, depending

upon the pectin content of the fruit. The usual way of testing this

point is to allow the jelly to drip from a large spoon. If it falls from

the spoon in wide sheets it is considered done. It is also usually done

when the boiling jelly forms large bubbles and apparently "tries to jump

out of the pot."

45.

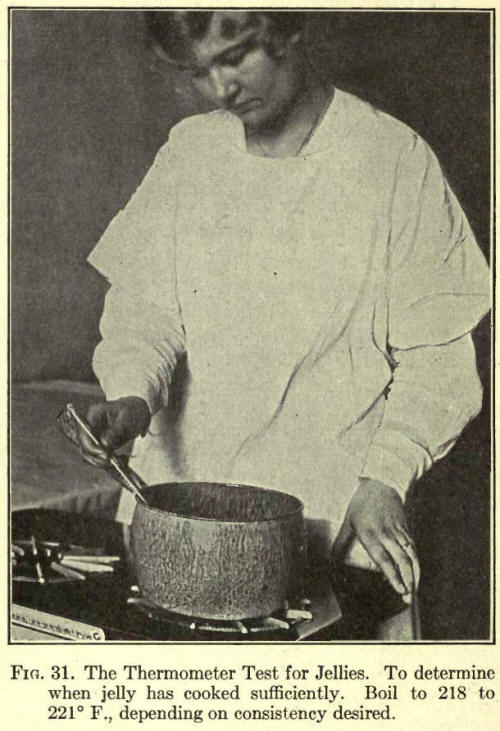

Thermometer Test. A more accurate test is the thermometer test. A

candy or other good thermometer is kept in the boiling liquid. As the

juice boils down the boiling temperature increases. When it reaches 221°

F. or 105° C., it has reached the proper point for a stiff jelly. The

thermometer must be kept well immersed in the boiling juice for this

test. (See Fig. 30.) 45.

Thermometer Test. A more accurate test is the thermometer test. A

candy or other good thermometer is kept in the boiling liquid. As the

juice boils down the boiling temperature increases. When it reaches 221°

F. or 105° C., it has reached the proper point for a stiff jelly. The

thermometer must be kept well immersed in the boiling juice for this

test. (See Fig. 30.)

When the boiling point reaches 221° F., it

merely indicates that the jelly contains 65% sugar. This will mean a

stiff jelly that will stand shipping, assuming that the fruit juice

contains sufficient pectin and acid. If a less firm jelly is desired, it

should be boiled only to 219 or 218° F. Often for household use such a

jelly is more desirable than a very stiff jelly. It must be remembered

than these figures apply only to fruits with a sufficient amount of

pectin and acid.

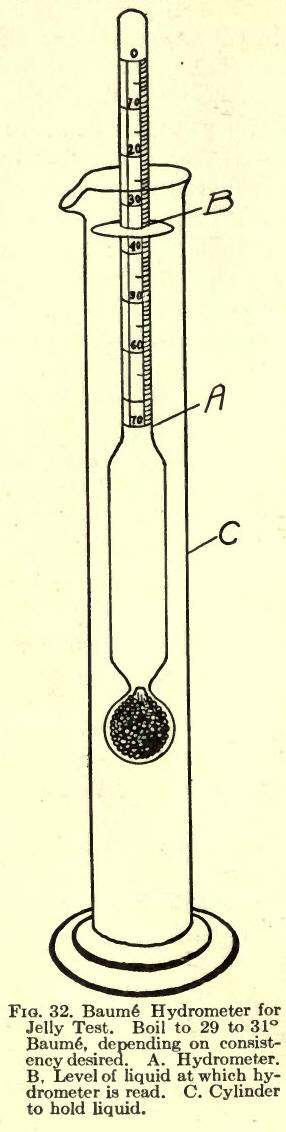

46. Hydrometer Test for Jelling Point. The various types of

hydrometers described under "Sirups for Canning" (see paragraph 11) may

be used to test the jelling point. Their use is not so convenient as

that of the thermometer. They are more certain and satisfactory than the

sheeting test.

While the jelly is boiling hot, pour it into a tall glass or tin or

copper cylinder: A tall narrow twenty-five cent flower vase, or a tall

narrow olive jar, or even a quart milk bottle will answer for a

cylinder. Insert the hydrometer and read the degree at the surface of

the liquid. When the test reads 32° Baume or 62° Brix or Balling in the

hot juice, a stiff jelly will result if the juice contains sufficient

pectin. Similarly, a "quivery" or less firm jelly will result at 29°

Baumc or 58° Balling or Brix, assuming that the fruit contains

sufficient pectin and acid.

47. Meaning of Thermometer and Hydrometer

Tests. These tests simply indicate that the jelly contains a certain

amount of sugwr and that boiling has concentrated the juice down to this

sugar content. It does not necessarily mean that one will always obtain

a jelly by boiling the juice down to the temperatures or Baume and

Balling degrees mentioned above. If the fruit is deficient in pectin and

acid or in only one of these constituents, jelly cannot be made,

regardless of the amount of boiling taking place.

On the other hand, if sufficient pectin and

acid are present, the above tests are very valuable in determining the

jelling point.

48. Pouring and Cooling the Jelly. Pour the jelly into glasses or

other containers. Paper jelly containers are now on the market which

answer the purpose very well. The glasses should be dry.

If the jelly is poured through a piece of

cheesecloth or tea strainer into the glasses, any coarse particles will

be removed. Allow the jelly to cool overnight before sealing with

paraffin. 49.

Coating with Paraffin. When the jelly has set, paraffin should be

added to seal it. If paraffin is added to the hot jelly the jelly

"sweats" or moistens the sides of the glass between the paraffin and the

glass. This causes the paraffin to become loose so that it no longer

protects the jelly. The hot jelly also decreases or contracts in volume

as it cools—the paraffin sets before contraction ceases and is apt to

not fit down closely on the jelly later.

If when the jelly is cold, the inside of the

glass above the jelly is wiped perfectly dry with a cloth or if the

jelly is allowed to stand until this part of the glass is absolutely

dry, the paraffin. will adhere perfectly when added.

Add the paraffin hot enough to sterilize the

top of the jelly. This will insure its keeping.

50. Sterilization of Jellies. If

jellies contain less than 65% sugar, i. e., the jelly tests less than

32° Baume or 62° Balling or Brix when hot, or boils at less than 221°

F., it may ferment or mold unless sterilized in sealed glasses or jars.

In the hot interior valleys of California housewives lose a great many

glasses of jelly by fermentation. Under such conditions the jelly should

be boiled down to the point noted above or should be placed in jars and

sterilized. This can be done by pouring the hot jelly into scalded jars

and sealing at once. The glasses are then immersed in water at the

simmering point for fifteen minutes to sterilize the rubbers and caps.

Such jelly will keep under all conditions of weather.

51. Jellies without Cooking. A few

fruits are so rich in pectin and acid that jellies can be made from them

without heating the fruit or the juice and sugar. Such fruits are

currants, loganberries, and cranberries.

Crush the fruit thoroughly and press out the

juice with vigorous pressure to force the pectin out of the pulp. Strain

as clearly as possible.

Two methods may then be used. By the first

method, add one and one-half cups of sugar to each cup of juice and mix

thoroughly until the sugar dissolves. Pour into glasses and place the

glasses in the sun for several days until the jelly becomes firm. The

sun evaporates the excess moisture. Bright sunlight is necessary. When

jelly has formed, seal with paraffin.

Jelly may also be made without sun

evaporation if two cups of sugar are added to each cup of juice.

52. Jelly. Stocks. The juice obtained

by draining or pressing the hot fruit after cooking may be sterilized in

bottles as directed for fruit juices (see paragraph 32) or poured

boiling hot into jars or cans and sealed without cooking. This juice or

"jelly stock" can be used by the usual method at any time by adding

sugar and boiling down to the jelling point. This economizes on jelly

glasses and results in fresher flavored jellies.

53. Crystallization of Jellies.

Crystals form in grape jelly from the separation of cream of tartar.

There is no certain way of preventing this. It can be greatly minimized,

however, if the juice is boiled down about one-half after pressing and

is then stored in bottles or jars for about six months before being made

into jelly.

Crystallization in other jellies is caused by the presence of excess

sugar. This may be caused by the sugar added in making the jelly or may

be caused by crystals of glucose, a sugar found in all fruits. It can be

prevented if the jelly is boiled down so that it contains not more than

70% sugar. The use of the thermometer and hydrometer tests will guard

against this common defect in jellies.

54. Marmalades. Marmalades differ

from jellies only in the fact that they have pieces of the fruit

suspended in the jelly. Fruits for marmalade must be rich in pectin and

acid.

The

principles of marmalade making are the same as for jelly making. First,

a portion of the fruit is boiled, pressed, and strained to give a pectin

solution. Part of the fruit is cut in thin slices, cooked till tender,

and added to the juice obtained by boiling and pressing. Sugar in equal

volume is added and the mixture boiled down to the jelling point. The

principles of marmalade making are the same as for jelly making. First,

a portion of the fruit is boiled, pressed, and strained to give a pectin

solution. Part of the fruit is cut in thin slices, cooked till tender,

and added to the juice obtained by boiling and pressing. Sugar in equal

volume is added and the mixture boiled down to the jelling point.

Orange marmalade is the best known. Dundee

marmalade is the standard. It is made in Scotland from the bitter

Seville orange shipped from Spain in brine. It possesses the peculiar

aromatic and bitter flavor of this orange.

In the United States the usual commercial

varieties of oranges, such as the Naval, Valencia, Mediterranean Sweet,

Satsuma, etc., are used in combination with lemons. Lemons furnish the

acid and oranges the pectin.

Grape fruit is also used a great deal for

inarrnalade, both alone and in combination with lemons.

Fruits rich in pectin, such as apples,

currants, and loganberries may be used as source of the pectin solution

and shreds of apricots, peach, watermelon rind, pear, quince, etc., may

be added to produce the marmalade effect. |